Barthes and Debord: The Cultural Work of Images in Late Modernity

For some time now, we have been engaging with the question of the image, observing its transformations, its drifts, and its increasingly central role in the construction of contemporary reality. This time, we aim to develop a reflection on how the visual entity has come to assert itself as a form of social power: today, the image is capable, in various ways, of organizing common sense, guiding behavior, and defining what appears relevant, desirable, and visible.

To do so, we return to two figures who, in different historical moments but with remarkable clarity, anticipated many of the dynamics that now permeate digital space: Roland Barthes and Guy Debord. Their reflections on the image, myth, and spectacle do not belong to the past; rather, they seem to describe with precision the current functioning of media, platforms, and systems of visibility.

In both cases, the image is understood as something that goes beyond representation. It becomes a device that produces reality, establishes social relations, and exercises a diffuse form of control without resorting to coercion. The power of the image lies in its ability to appear natural, neutral, and inevitable, while actively constructing a shared worldview.

To reread Barthes and Debord today means to interrogate the present with tools that remain extraordinarily effective, and thus to recognize that the condition of the image as spectacle is not a superseded phenomenon, but a structural condition that has further intensified, to the point of coinciding with everyday experience. In this context, reflecting on the image is equivalent to reflecting on how power manifests itself, is distributed, and renders itself invisible.

The Image as the Construction of Common Sense

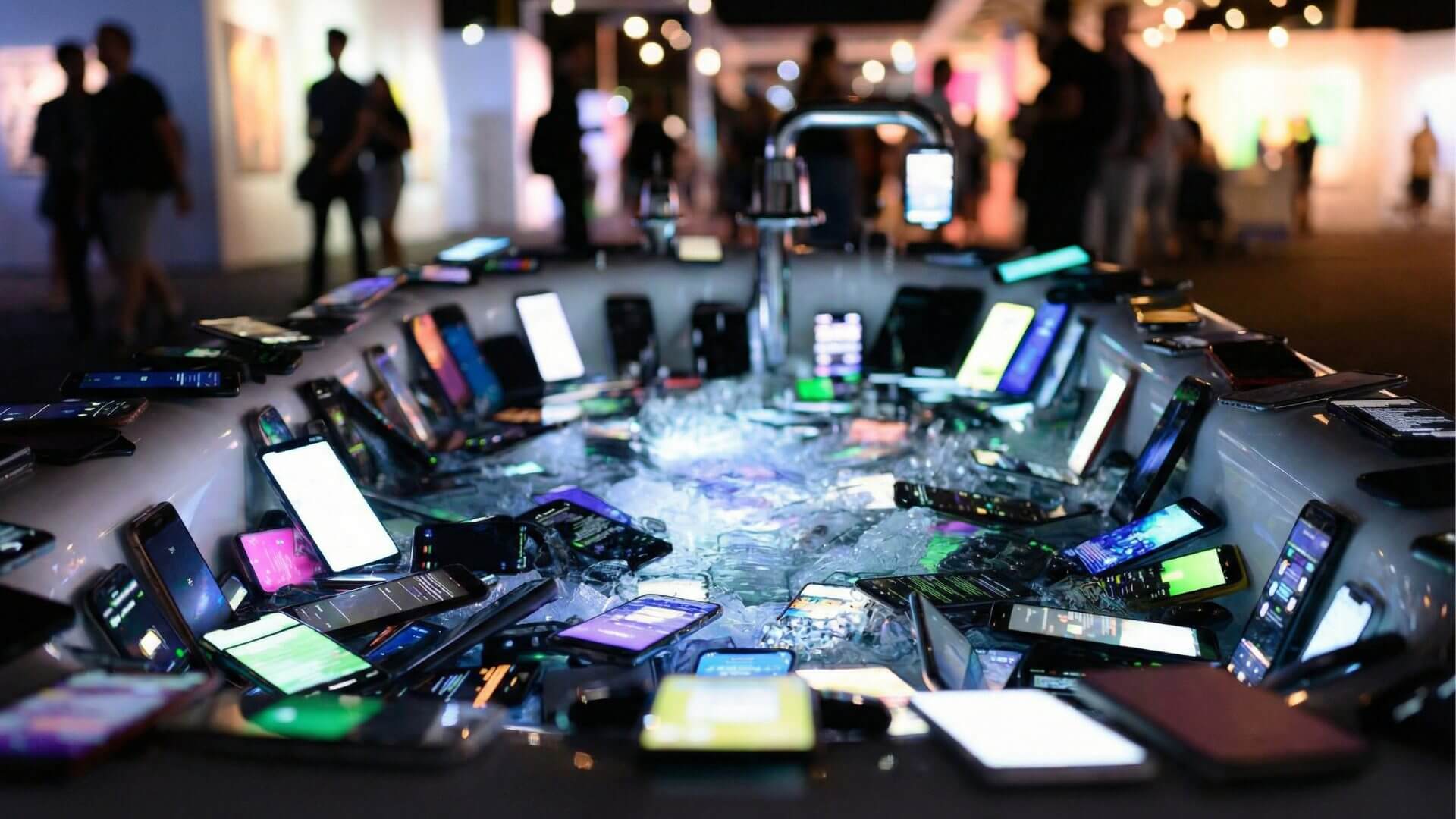

Last year, we happened to find ourselves in a park, sitting on a bench, observing an apparently banal scene. A group of people, spread across the space, all engaged in the same gesture: their gaze fixed on a screen. No direct interaction, no dialogue. Only similar postures, synchronized rhythms, minimal movements. Nothing extraordinary was taking place, and precisely for this reason the scene was eloquent. Nothing was happening, yet everything already seemed organized.

At that moment, the feeling had little to do with the use of technology and much more with something subtler. It was as if reality had become a backdrop, a passive support for a flow of images taking shape elsewhere. The park was no longer a space of experience, but a place of waiting. What mattered was happening somewhere else, within the shared visual space of screens.

That episode made clear how the image no longer functions as a representation of reality, but as a structure that precedes it and organizes it. This is precisely the point identified by Roland Barthes when he analyzes the workings of myth: the image presents itself as natural, immediate, devoid of any apparent construction. Meaning is not perceived as a cultural product, but as self-evident.

From this perspective, the image does not ask to be interpreted. It asks for adherence. Through repetition and familiarity, it establishes a common sense that imposes itself without declaring itself. A historical, social, or political value loses its origin and settles into the gaze as a given. Power operates by making itself invisible, blending into normality.

Today, this mechanism is even more evident. The images that move daily across our devices do not merely describe the world; they define its perceptual coordinates. They decide what appears relevant, what deserves attention, what exists socially. The visible becomes a criterion of truth.

Barthes identifies in this shift a decisive threshold: the moment when language ceases to be recognized as such and turns into environment. The image no longer communicates a message; it constructs a horizon. Within that space, common sense takes shape and power is exercised without needing to declare itself, acting directly on everyday perception of reality.

The Spectacle as a Total Environment

Returning to the episode in the park, a few months later we encountered a similar scene in a completely different context. A waiting room: people seated side by side, all immersed in the same visual flow. Not the same content, but the same posture. Waiting, suspended attention, continuous scrolling. At that moment it became clear that we were not observing individual images, but a shared condition—a way of being in the world.

This is precisely where the thought of Guy Debord becomes unavoidable. For Debord, the spectacle does not coincide with an accumulation of images, but with a mode of organizing reality. The spectacle is a social relation mediated by images. It does not merely show something; it structures how individuals relate to one another and to the world.

Within this configuration, direct experience loses its centrality. Life shifts onto a representational plane, where what matters is what appears, what circulates, what is recognized as visible. Reality does not disappear, but is reorganized according to its representability. To live means to witness, to observe, to follow.

The spectacle operates as a total environment. It does not present itself as an explicit ideology, but as an implicit horizon. Everything passes through it: information, entertainment, politics, desire. The individual does not experience the spectacle as an external imposition, but inhabits it as a normal condition. The separation between the one who looks and what is looked at becomes structural.

Debord identifies in this process an advanced form of power—a power that does not command, but arranges; that does not forbid, but orients. The image does not distract from reality; it progressively replaces it, offering a mediated, organized, continuously accessible version. Participation gives way to contemplation, action to consumption.

Read today, this analysis appears with almost disarming precision. The incessant flow of content, the centrality of visibility, the competition for attention all confirm Debord’s intuition: the spectacle is not a sector of society, but its dominant language. A language that transforms social life into a sequence of shared images, regulating behavior through the constant promise of presence and recognition.

In this space, the image definitively ceases to be a means. It becomes structure. And power, rather than imposing itself from above, disperses across the surface of the visible, making the spectacle the very form of contemporary experience.

From Image to Power: an Unexpected Convergence

While discussing this text among ourselves, we realized that many of the images we scroll through every day are not remembered individually. What remains are formats, gestures, postures, atmospheres. Not the content, but the recurring form. It is as if the image had stopped communicating something specific and had begun teaching us how to look, how to react, how to be.

It is at this point that the thinking of Roland Barthes and Guy Debord converges with surprising coherence. Both identify the image as a device that operates upstream of content, acting directly on perception and social behavior.

In Barthes, myth functions as a mechanism of depoliticization. The image empties reality of its historical complexity and returns it as self-evident. In Debord, the spectacle organizes the world as continuous representation, transforming social life into a sequence of shared appearances. In both cases, power does not present itself as imposition, but as normalization.

The image exercises power precisely because it does not appear to do so. It does not command, argue, or justify. It simply shows itself, circulates, repeats. Its force lies in continuity, familiarity, and its capacity to occupy perceptual space until it becomes environment. At this stage, power no longer governs through prohibitions, but through internalized visual models.

This theoretical convergence reveals a crucial shift: social control no longer acts primarily on the body, but on the gaze. To determine what is visible is to determine what is thinkable. The image becomes a technology of orientation, capable of producing consensus without declaring it, of guiding desire without formulating it explicitly.

Today, this dynamic appears amplified. Images not only circulate, but are measured, optimized, and pushed. Algorithms of visibility reinforce what performs well, what captures attention, what confirms expectations. The power of the image thus intertwines with automated systems that multiply its effectiveness, rendering the process even more opaque.

Read together, Barthes and Debord allow this structure to be recognized with clarity. The image emerges as a form of social power precisely when it ceases to appear as a tool. It becomes the dominant language, a shared space, a condition of experience. And it is in this total normalization that its power reaches its highest degree of effectiveness.

The Spectacle Today: an Internalized Condition

In recent years, we have noticed that the distinction between inside and outside, between experience and representation, has become increasingly difficult to trace. There is no longer a clearly separate moment in which one “watches” something and then returns to life. Life itself takes the form of a continuous visual sequence, potentially exposable, shareable, measurable.

In this sense, the society of the spectacle described by Guy Debord reaches a further stage. The spectacle no longer operates as a distance between reality and image, but as their overlap. The individual does not simply observe the world through images, but learns to perceive themselves as an image. Identity is constructed in relation to visibility, recognizability, circulation.

At the same time, the myth analyzed by Roland Barthes becomes more refined. Contemporary images no longer merely naturalize values or ideologies, but entire lifestyles, emotional postures, ways of existing. What appears on the screen does not suggest what to think, but how to be. The power of the image shifts from content to the implicit form of life it proposes.

Within this configuration, control no longer operates through prohibition, but through spontaneous adherence. The spectacle is internalized as a desirable horizon. The subject actively participates in their own exposure, contributing to the reproduction of the system that governs them. Power disperses across the surface of the visible and is reinforced through the unconscious collaboration of those who inhabit it.

The contemporary relevance of Barthes and Debord lies precisely in their ability to read the image as structure rather than as an isolated phenomenon. Their analyses make it possible to understand how contemporary power operates in a diffuse manner, without an apparent center, through the management of the gaze, attention, and desire.

Today, the society of the spectacle does not impose itself as an exception, but as a normal condition of experience. The image becomes the site where the social takes shape, legitimizes itself, and reproduces itself. To question it, then, is to question the present itself, recognizing that power, rather than hiding behind images, now operates through them, making them the everyday fabric of collective life.

fakewhale

Founded in 2021, Fakewhale advocates the digital art market's evolution. Viewing NFT technology as a container for art, and leveraging the expansive scope of digital culture, Fakewhale strives to shape a new ecosystem in which art and technology become the starting point, rather than the final destination.

You may also like

Šárka Koudelová, Petrichor at PRÁM, Prague.

Petrichor by Šárka Koudelová, curated by Edita Malina and Světlana Malina, at PRÁM, Prague, 6/1

Blessend in Conversation with Fakewhale

Introducing Blessend Artist: Blessend – Birthplace: Sardinia, Italy, early 90’s –

Fakewhale in Conversation with Operator

Today, few artistic collaborations stand out as distinctly as Operator, the dynamic duo of Ania Cath