The Power of Cute: Review of the 13th Berlin Biennale by Sofia Baldi Pighi

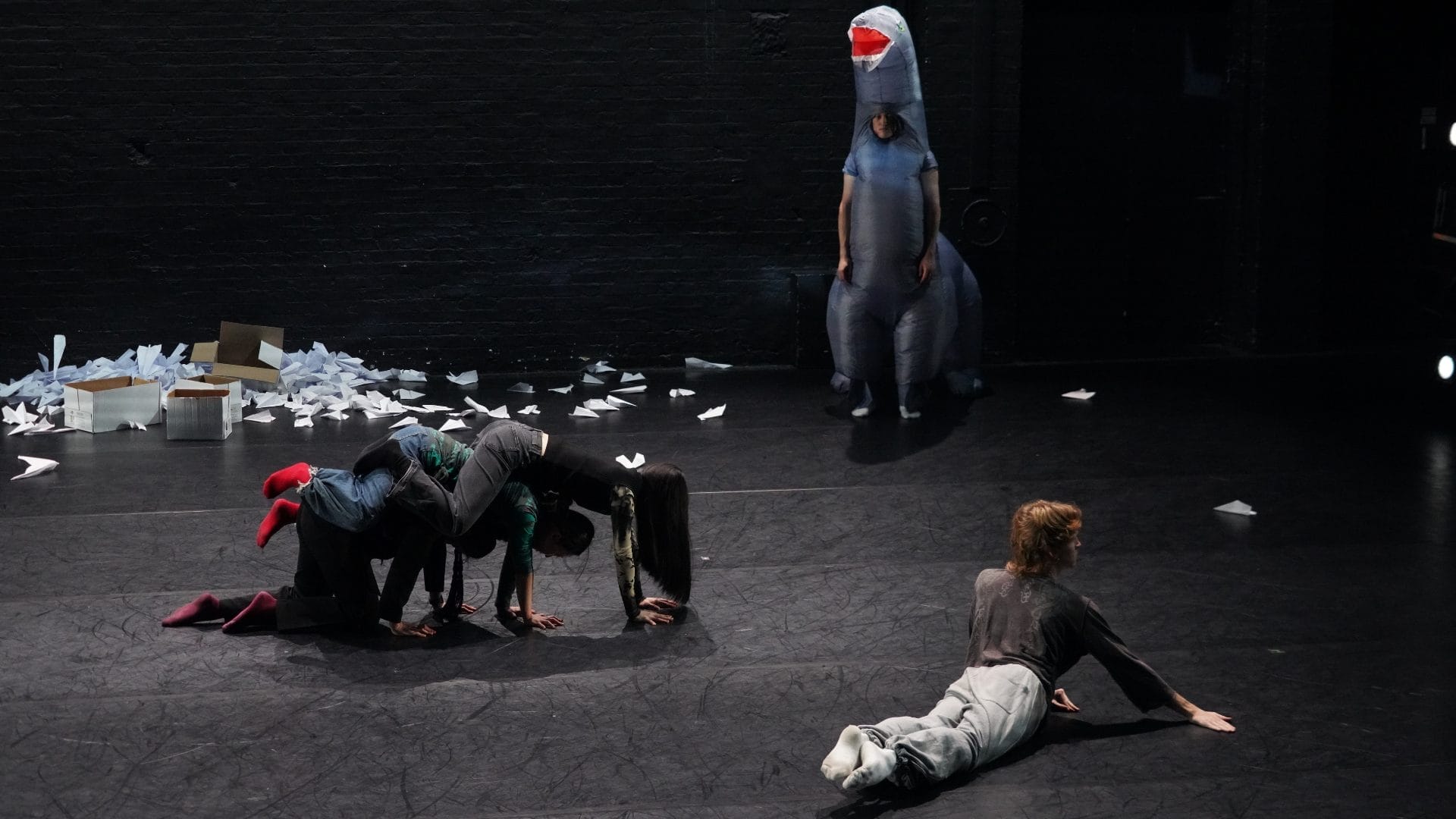

From rhetoric to whisper, the 13th Berlin Biennale adopts a deliberate posture of political engagement. It looks sideways, renounces slogans and the monumentality of frontal denunciation, and instead prefers a critical discourse whispered in the ear. This edition investigates fugitivity, understood as a cultural capacity to evade and reimagine oppressive frameworks. It is described as the ability to construct illegality within contexts of unjust laws, like a cunning fox finding divergent solutions in moments of danger. An artwork, for example, can establish its own laws in the face of legalized and systematized violence.

Curators Zasha Colah and Valentina Viviani stress that the concept of the 13th Berlin Biennale is not a statement or a thematic frame, but rather a true operational strategy for disentangling from multiple institutional pressures. Following the technique of foxing, a strategy inspired by the fox’s ability to elude capture, the curatorial team decided not to reveal the artists’ names until the very end, despite heavy pressure from the press, in order to protect both their works and their loved ones (many relatives of the participating artists still live in the regions under scrutiny). As Viviani writes, “to encounter implies the unforeseen quality of the meeting… like when we encounter a fox in the city at dawn.” This notion of the encounter – sudden, fleeting, transformative – frames the Biennale as a space where both artists and audiences carry away the traces of what they have met. For many artists in the Biennale, research is not merely thematic; artistic practice becomes a way of living, and vice versa. Their investigations merge with lived experience, and in several cases pseudonyms are used to protect their identities.

In this shift from frontal denunciation to lateral critique, one aspect I especially admired in Colah and Viviani’s curatorship of the 13th Berlin Biennale is tenderness. In his book The Power of Cute (2019, Princeton University Press), British philosopher Simon May argues that “the cute” offers a playful escape from pressure. Cute does not shout, but it resists. It embraces ambiguity, flirts with the unspoken, and allows fragile, hybrid identities to take shape. It does not march, but slips into structures, softens them, ridicules them. It is a form of soft power that counters oppression with the strength of sweetness, the disobedience of play, the seduction of tender gestures.

One of the most iconic works of what I would call “The Power of Cute” in the 13th Berlin Biennale is Chinese artist Han Bing’s performance Walking the Cabbage. Ongoing since 2000 in Beijing, beginning in Tiananmen Square, the work consists of a small cart with tiny wheels carrying a large cabbage. Pulled by the artist, the cart exits the museum and moves through the city. After just a few steps, this walk reveals itself as entirely un-monumental, closer to awkward stumbles than to grand public parades. On the contrary, it is clumsy and frequently interrupted: the cart gets stuck, steps are too high, weaving between cars is difficult. Watching the cart stumble over countless speed bumps or get blocked by steep stairways, I cannot help but think of all those, elderly citizens, or adults and children in wheelchairs, who face similar struggles in everyday urban movement. Who would have thought that a cabbage on a tiny cart could make me reconsider Henri Lefebvre’s concept of the right to the city (Le droit à la ville, 1968), and the idea of urbanité, which, unlike urbanisme, concerns those who actually live urbanity, the citizens as symbiotic organisms intertwined with the places they inhabit.

Step by step, a secular procession unfolds in public space: a group of visitors begins walking, following the artist and their cabbage. Within minutes, the absurd pursuit shifts our collective perception: from a cluster of strangers, we have become a collective movement, accomplices in this bizarre endeavor. The artist plays with the surreal to reveal how absurdity can harbor subversive potential. Resistance here is not born of grand gestures but spreads through laughter and irony. As Viviani reminds us, “At first sight, these actions might seem innocuous, but by tuning in we glimpse the freedoms they smuggle in and out. Laughter here works as a response, a way of saying: I hear you, I’m with you.”

“If during Carnival every prank is fair,” Italian artist Piero Gilardi fully embraced the ridicule of power by creating puppets during Trump’s first administration, works that remain disturbingly relevant at KW in 2025. Carnivalesque in aesthetic with a post-surrealist edge, his soft sculptures remind us that subversion is always irreverence toward the powerful.

From Gilardi’s puppets we move to Big Mouth, the stand-up comedy room by Bosnian artist Mila Panić. For one week, she performed alongside a Berlin-based comedian in a bar created specifically for stand-up at KW. Every chair and table bore inscriptions by the artist, phrases drawn from “bar talk,” steeped in dark humor. During my visit, I saw audience members searching for the sharpest lines, then laughing and exchanging complicit glances.

Within this “Power of Cute,” one cannot overlook the extraordinary tragicomic work of Sawangwongse Yawnghwe. The artist, originally from Myanmar and the son of the country’s first democratic prime minister, reconstructed the model of the presidential palace where he lived as a child, placing it at the center of a large hall at KW transformed into a lair. Cherry-red therapeutic lamps shone from the small windows of his hideout. Over two years of research, Yawnghwe collected data from around the world to describe in detail the global arms race. A notorious dataset of worldwide military investments was repackaged as a resounding restaurant menu, “appetizers,” “first courses,” “main courses,” “side dishes,” and “desserts”, listing the weapons produced or purchased by arms manufacturers across the globe.

Curator Duygu Örs, Co-Head of Education and Mediation at the Berlin Biennale, emphasized that this is the first time education and mediation were conceived not as subsequent to artistic and curatorial decisions, but simultaneously. Reading the program of the Biennale’s Public Program, the special role of artists is immediately evident. These events, at least two each week, were understood by the curators as opportunities to probe and intensify artistic practices: “these are moments that require presence,” explains Viviani. Among them, the People’s Tribunals stand out: community-sourced judicial forums addressing human rights violations and crimes against humanity when justice has been denied. In the Biennale’s program, The People’s Tribunal on Art for Resisting Oppression, Philippine Cases put state forces on trial for their coordinated attacks on artistic and cultural rights. Testimonies came from Filipino artists who are grassroots organizers, some now in exile in Europe due to persecution, others still facing repression at home. At the heart of the Tribunal lies the recognition that the right to cultural expression is inseparable from political and economic struggles.

The display of the 13th Berlin Biennale refuses to build new walls, relying instead on silent resistance and the subversive power of cute. Across its galleries, it questions monumentality in order to assume a political posture of whispering, resisting without shouting, like the foxes of Asian legends. Just as foxes appear at night in Berlin’s museum gardens in packs inhabiting invisible spaces of belonging, the so-called fox circles, liminal zones that redefine community, so too does the Biennale draw inspiration from foxing as a curatorial strategy and practice of inquiry.

The tenderness of this Biennale, in this sense, is political. Not because it proclaims a struggle, but because it opens an alternative space where rules can be silently rewritten. Beyond visitor numbers and critical reviews, the success of a biennale lies in the impact it generates within the cultural fabric of the city. The resonance of the 13th edition lives on in countless free activities of the public program, which, starting from the artworks, functioned as devices of education and counterculture. Schools and universities have already embraced the exhibition as a tool for independent learning. The 13th Berlin Biennale shows that resistance can be whispered, smuggled, even laughed into being. Against the roar of oppression, it asserts the disobedience of play and the strength of tenderness. Cute, here, is not harmless decoration, it is a weapon, wielded softly yet incisively, rewriting the rules of what it means to be political today.

Sofia Baldi Pighi

Sofia Baldi Pighi is an Italian curator and PhD candidate based between Milan and Gozo, Malta. Since 2017, her practice explores the intersection of art, historical heritage, and militant politics through exhibitions, public programs, and workshops. She is the Artistic Director and Head Curator of the Malta Biennale 2024, Insulaphilia, promoted by Heritage Malta and UNESCO. Baldi Pighi was part of the curatorial team for Italy’s first National Pavilion at the 14th Gwangju Biennale in South Korea (2023). She collaborates with institutions across Europe and Asia, including UNESCO-WHIPIC, Triennale Milano, Larnaca Biennale, and MOKA Museum. Baldi Pighi also works with international galleries and companies supporting art projects. She is a member of Art Workers Italia and IKT - International Association of Curators of Contemporary Art and contributes to publications such as NERO, Exibart, Modern Times and Fakewhale LOG.

You may also like

Sasha Stiles in Conversation with Fakewhale

In this conversation with Fakewhale, Sasha Stiles, a first-generation Kalmyk-American poet, artist,

Julie Insun Youn, “Instant Trance” at Platform-L Contemporary Art Center, Seoul, South Korea.

“Instant Trance” by Julie Insun Youn at Platform-L Contemporary Art Center, Seoul, South

Mouth Wash and Razor Blades: A Playground of the Surreal

“As I watch ‘Mouth Wash and Razor Blades’, I feel as though I’m spiralling through a hal