Fakewhale in dialogue with S. Mercure

In S. Mercure’s work, the exhibition space is never a passive container, it becomes a sensitive surface, a listening body, an active agent of transformation. His pieces do not simply inhabit space; they absorb its invisible residues, dust, humidity, shadows, vibrations, translating them into gesture, image, and pigment.

At a time when the sterile whiteness of the white cube seems intent on erasing all traces of time, Mercure intervenes precisely there: where architecture seeks invisibility, he reveals its memory. In our conversation with Fakewhale, we delved into these quiet gestures, this material and poetic archaeology, where each work emerges from a singular, unrepeatable relationship with its context. Here, even documentation, understood as the construction of a reality, becomes an integral part of the work itself.

In your artistic practice, the exhibition space is never a mere container; it becomes a material to be shaped and revealed. What does it mean for you to work with this kind of “physical intangibility,” and how has your research in this direction evolved over time?

The exhibition space has never been a mere container. Since art history cannot be fully understood without considering the place where art is received, it seems impossible to reduce it to a space of reception. For me, and I’m convinced for many others, the white cube is an object of fascination. I became interested in it by researching its evolution, both through its representation and its role in disseminating artworks on digital platforms. While this is a topic to revisit, my current practice developed from this core idea: even when fully constructed, fictional, or physically inaccessible, the white cube continues to inform the work, infusing it with content and meaning. From this perspective, I seek to reaffirm a physical link, a tangible interdependence between artwork and its presentation site, that is, to create work that materially emerges from its context. The challenge lies in finding an element constitutive of the space, yet imperceptible or symbolic. The white cube is designed to be as neutral as possible, so as not to “contaminate” the work it presents. This invisibilization of its architectural features fascinates me, and over time I’ve become increasingly sensitive to it. When visiting exhibitions, I began to observe the display structures more than the artworks themselves. Paradoxically, the identity of the space often reveals itself most fully in emptiness, when it seems there is nothing left to see.

In EXTRACTION you transform seemingly invisible elements—dust, humidity, shadows, into tangible substances and images. How important is it for you that the audience perceives this process of transformation, rather than just the final outcome?

I consider the primary value of the work to reside in the process that leads to its realization. At the same time, achieving an aesthetic outcome through this process is also an essential goal. I am fascinated by the delicate balance between conceptual and aesthetic value, a balance central to the practice of many conceptual artists who inspire me. These two aspects often speak to different audiences, and ultimately, how the finished work is received is beyond my control. Because of this, what I find most meaningful can sometimes lose its significance in the eyes of the viewer. That said, I see the paintings from the EXTRACTION series as embodying a dialectic, their aesthetic appeal simultaneously generates and deconstructs an illusion, reflecting Marx’s concept of commodity fetishism: the object’s value appears to reside solely in its presence, yet in reality, it is grounded in the process, the method, and the complex network of symbolic materials and social relations involved in its creation. What plays against that illusion is the very support of the paintings, a transparent PVC stretched over a frame. Some areas are not fully covered by the paint, allowing the surface to reveal the wall behind. In this way, the exhibition space itself becomes part of the artwork, integrating the environment into the visual experience. Therefore, even if the work is appreciated only for its formal qualities, the underlying material and concept remain present within the frame, subtly yet decisively shaping the viewer’s encounter.

Acts such as sanding the walls, collecting water, or documenting shadows carry both poetic and almost ritualistic qualities. Can these gestures be understood as a form of “archaeology of space,” capable of restoring silent and layered memories?

When I first approached the idea of extraction, my motivation was to work with what is often non-visible and intangible. I also wanted the work to be fundamentally representative of the space’s identity, an imprint that would inevitably involve the history embedded within it. When an exhibition is taken down, the gallery is returned to its default state. One common strategy for this is repainting all the walls with the original color. But to me, this act is more than just restoration, it is a renewal that encapsulates the temporality of what came before. The space does not simply regenerate a new skin; it holds within it a layer of time, suspended between the old and the new. By sanding this surface, even lightly, it becomes possible to excavate traces of the past, releasing hidden meanings that would otherwise remain sealed beneath. As for the collected water, this element feels more symbolic and poetic. Liquefying the atmospheric essence of the space touches on more dynamic and ephemeral qualities. It evokes the traces of those who moved through it, temperature fluctuations, bodily presence, and moments when the outside world pierced this sealed interior. These subtle imprints, suspended in time, are what I aim to draw out. The documentation of shadows, ephemeral and immaterial—echoes this same logic. Shadows are neither presence nor absence, but the trace of a body in space. By capturing them, I am not preserving the object itself, but rather the space it occupied, the light it interrupted, the time it inhabited. Altogether, these gestures reveal conditions of presence, of transition, of impermanence. It does not seek to restore a fixed past, but to activate what still lingers, a quiet memory embedded in material, atmosphere, and image. In this sense, the work becomes a kind of sensorial archaeology, one that unearths not objects, but the layered memory of space itself.

The fusion of dust and water into a paint that “embodies” the extracted space blurs the boundaries between destruction and creation. Are you more interested in the fragility of the gesture itself, or in the possibility of generating new forms of continuity through matter?

Looking back now, the word “destruction” feels a bit strong. What I want to emphasize is that the extraction process, although sometimes labor-intensive, is very subtle and respectful. Most galleries I’ve collaborated with on this project couldn’t even tell the difference between the space before and after my intervention. You really have to look closely to notice that anything has been altered. To answer more directly: I am equally interested in both the gesture and the possibilities it opens up. These two aspects are deeply interconnected and interdependent. The work needs the extraction to exist, and the space needs the work to be perceived. It is this dynamic relationship between the process and the residual artifact that gives the work its meaning. Removing either component would be detrimental. Also, and this might not be obvious yet, the work is never actually returned to the location of extraction. Instead, it is realized virtually through the construction of detailed documentation of the exhibitions. While images are produced in this process, what I am really creating is an extended record, an experience, that makes the work possible beyond the physical site. In this sense, the artifact is not an end in itself but an opportunity to extend the dialogue further. I am currently working on a printed publication whose status remains intentionally ambiguous. This opens up the possibility of experiencing the work in new ways and touches on broader themes that interest me, such as our perception of reality, how we distinguish what is real from what is not, what has happened from what only seems to have happened. The work plays with this ambiguity, inviting viewers to question the boundaries between presence and absence, fact and illusion, memory and projection.

In Seven Sites at FORM, the tension intensifies with the introduction of the “seventh space”, a place that does not participate in the extraction but instead hosts the residues of other sites. How central is this dynamic of hospitality and estrangement within the exhibition context?

Seven Sites represents a detour from my main line of research, though it still uses EXTRACTION as its point of departure. Whereas EXTRACTION is built around an exclusive relationship between a single space and the small series of works it makes possible, Seven Sites shifts that dynamic: each work in the series contains a mixture of materials, powder and water—collected from six different locations. As an anecdote, these works ended up slightly darker than others. One of the six participating sites only allowed access to a section of the gallery that is permanently painted black, due to its function (used for projections, for example). As a result, one sixth of the powder used in the final mixture was black, subtly darkening the overall tone of the paint. At some level, any artwork introduced into an exhibition space acts as a foreign body. Of course, this can be debated, especially if you believe that a fair share of artworks are created with the white cube in mind, even unconsciously. Still, their presence disturbs a certain spatial equilibrium, one that is only fully visible when the space is empty. In Seven Sites, however, the tension comes not only from introducing an object into the space, but from the nature of the object itself. The material that enters the seventh site comes from other spaces of the same kind and function. The space, in a way, is receiving imitations of itself, reflected through its institutional counterparts. This creates a kind of circular contamination, or reciprocity, between spaces that are usually kept distinct but nonetheless connected.

The notion of “extractivism” resonates on both cultural and ecological levels, and in your work these dimensions intersect. How do you experience the relationship between the artistic gesture and the ecological responsibility inherent in extracting and transforming the materials of a place?

I think the term ecology here can be understood as the relationship between the environment and the artifact produced from its extracted materials. Metaphorically, this interdependence echoes how we, too, are shaped by and dependent on our surroundings, and how even the slightest alteration to an environment can have lasting effects. Ecological responsibility, then, lies in creating something that feels true to the initial milieu, encouraging a sense of reciprocity rather than exploitation. On another level, I often think about a sentence from Joshua Simon’s Neomaterialism: “But insofar as every artwork starts with some mode of consumption, every art object begins with shopping.” I may have taken this line somewhat out of its original context, but it resonates with me. It reminds me that ideas and creative processes don’t emerge from nowhere, they arise from our engagement with the material world. From this perspective, even the conceptual act of focusing on a material could be understood, within a certain economic framework, as a kind of consumption. By acknowledging and integrating that awareness into the process, I try to approach my gestures more consciously, seeking a respectful balance between the act and the space, a balance where the work doesn’t just occupy it, but reflects it.

Your practice seems to engage both with the conceptual tradition of dematerialization (Lippard, absence, documentation) and with the return to materiality and neomaterialism. How do you position your research within this balance between idea and substance?

I think neomaterialism offers a compelling lens through which to revisit the legacy of dematerialization in conceptual art. With a more open and generous understanding of what materiality can be, it seems inevitable that material concerns would resurface, even within practices traditionally framed as contributing to dematerialization. I try to approach materiality with that same openness, positioning my research dynamically within the interplay of idea and substance. It’s not so much about achieving a balance, but rather sustaining a movement, a back-and-forth between the conceptual and the material, the visible and the non-visible, and so on. By keeping the gesture in motion, these apparent oppositions shift from fixed categories to becoming frameworks through which to explore experience and perception. It’s this ongoing movement that allows the work to occupy a space where substance and idea are not separate, but continuously inform and reshape one another.

Your works often encourage viewers to look beyond what seems obvious, as in Everything Means Something When Someone is Looking, where banal spatial elements revealed another layer of visibility. How important is it for you to destabilize perception and draw attention to what normally remains unseen?

With this first project at FORM, I wanted to explore, like you said so precisely, different layers of visibility. The idea emerged when I came across a small lot of blank insert adapters at a discount shop. These inserts are used as placeholders in light switch sockets when the actual switches haven’t been installed yet, or have been removed. One of them immediately spoke to me. It carried something beyond its material presence, it hinted at both function and banality, and how these two qualities often erase objects from our attention. When someone enters a space and expects to encounter something in particular, it can be surprisingly disorienting to find an absence instead. I became interested in that feeling of emptiness, not as a void, but as a subtle friction that could shift perception. For me, a powerful way to make someone look differently at an object, or a space, is to create a context where expectations don’t quite align with what is actually happening. The subtlety and banality of the inserts became my first method to achieve this: as I wrote in the accompanying text, “We look for them, but we do not see them.” The second method was rooted in the function, or rather, their refusal of it. These inserts had the same form as a light switch but denied the interaction we expect. That refusal pulled them out of invisibility. They didn’t interrupt their purpose, they withheld it. I was later able to name this phenomenon while reading Timothy Morton’s All Art is Ecological, where he references Heidegger’s concept of the “present-at-hand.” Funnily enough, Morton uses the light switch as an example: “Things aren’t directly, constantly present. They only appear to be when they malfunction, or are different versions of the same thing than we’re used to.” That idea clarified what I had intuitively been working with. By introducing a slight uneasiness into the space, I hoped to draw viewers into different active modes of looking. The experience was no longer passive, it became a search, an attentiveness to what can be easily overlooked.

Your projects also carry a critical reflection on institutions and the role of exhibitions as sites of legitimization. In an era where documentation often outweighs the duration of the exhibition itself, how do you navigate this tension?

These considerations are at the core of my practice. So far, every iteration of my project has been made visible exclusively through documentation images. In that sense, I play directly with the “duration” of the exhibition, not as a temporal event, but as a constructed representation. As I mentioned earlier, exhibition spaces became a kind of fascination for me, not only for their formal qualities, but for their role in shaping how artworks are perceived, contextualized, and legitimized. Today, I think it is fair to say that I experience at least 80% of exhibitions through documentation images on online platforms. This shift in how we “consume” art is not neutral; it has significantly changed the function and status of the installation photograph itself. I often return to Loney Abrams’ article Flatland, where she suggests that exhibition documentation should be considered an artistic medium in its own right. I take this seriously in my own process, composing the documentation with care: adjusting lighting, removing or emphasizing architectural features, subtly altering proportions. These decisions are not secondary to the work; they are part of its material construction. Abrams also argues that the gallery has, in many cases, lost its traditional function as a place of public reception, becoming instead a mere backdrop for the installation photo. That idea stays with me. What interests me most is that the legitimizing power of the white cube still operates, even through representation. It no longer needs a physical address to shape our perception of the artwork. The aura of the institution survives in the image. In my EXTRACTION series, for instance, the paintings, produced from the material and atmosphere of a specific site, are reintegrated into the space through digital gestures. In the documentation, the painting “returns home,” albeit conceptually. Sometimes, these images become the only visible manifestation of the work. What fascinates me is that, even when it’s unclear whether the exhibitions actually occurred or whether the spaces are physically real, the documentation has the same effect on the work’s perceived legitimacy. In this context, documentation is no longer just a record, it becomes both medium and matter.

Looking ahead, do you imagine your research on extraction and the transformation of space evolving in new directions? Are there materials, sites, or methodologies that you feel compelled to explore in the near future?

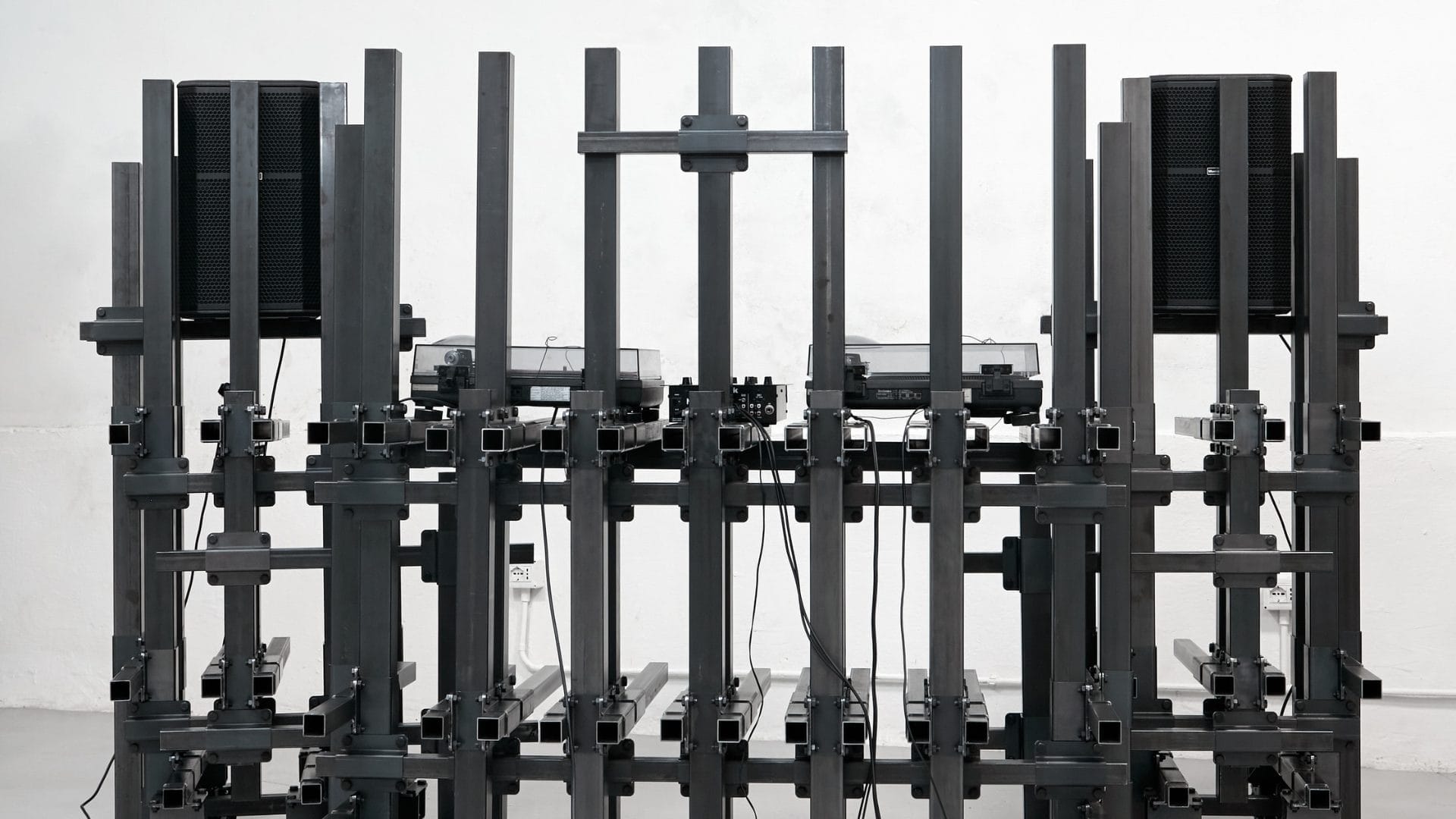

One of the things that surprised me most throughout this project was returning to “painting”, or at least producing an object associated with that tradition. It wasn’t my initial intention. One could say that the nature of what I extracted led me there almost inevitably, but still, it was unexpected. That experience opened up a space I now want to explore further by applying the same conceptual framework to different kinds of artefacts. I’m especially drawn to materials I previously overlooked or ignored altogether, like light and sound. Both carry spatial and atmospheric qualities that feel increasingly relevant to my ongoing research. I imagine returning to the same kind of sites, but through a new lens, tuning in to what they emit rather than what they shed. In that way, the process of extraction could continue, but this time from residue to resonance.

fakewhale

Founded in 2021, Fakewhale advocates the digital art market's evolution. Viewing NFT technology as a container for art, and leveraging the expansive scope of digital culture, Fakewhale strives to shape a new ecosystem in which art and technology become the starting point, rather than the final destination.

You may also like

Ju Young Kim, Aeroplastics at Academy of Fine Arts in Munich, Munich

“Aeroplastics” by Ju Young Kim, at Academy of Fine Arts in Munich, Munich, 8/02 –

Fakewhale in conversation with KiefferWoodtli

There’s something profoundly tactile, though entirely invisible,in the installations of KiefferWoo

Fakewhale Meets Domenico Romeo: On Modularity, Meaning, and Multiform Practice

We’ve been closely following the work of Domenico Romeo with great interest. As an artist, designe