Crafted for Your Attention: As Predictable as Art

There’s something deeply alluring about predictability. It’s like a mental embrace, a kind of linguistic stillness that shields us from the unknown. Everyday communication rituals, “How are you?”, “Good, and you?”, aren’t meant to inform, but to affirm. They’re gestures of inclusion, cultural signals that say: We’re speaking the same code. Just like we laugh at a TikTok sketch not because it’s new, but because the gag is familiar.

The human mind isn’t built for the unknown, it’s an obsessive pattern-recognition machine. It wants to see what it’s seen before, to feel safe within familiar forms.

This same logic, subtly reactionary, seeps into the world of art as well, precisely where we’d expect openness, risk, and movement toward the unfamiliar.

The Shape of Reassurance

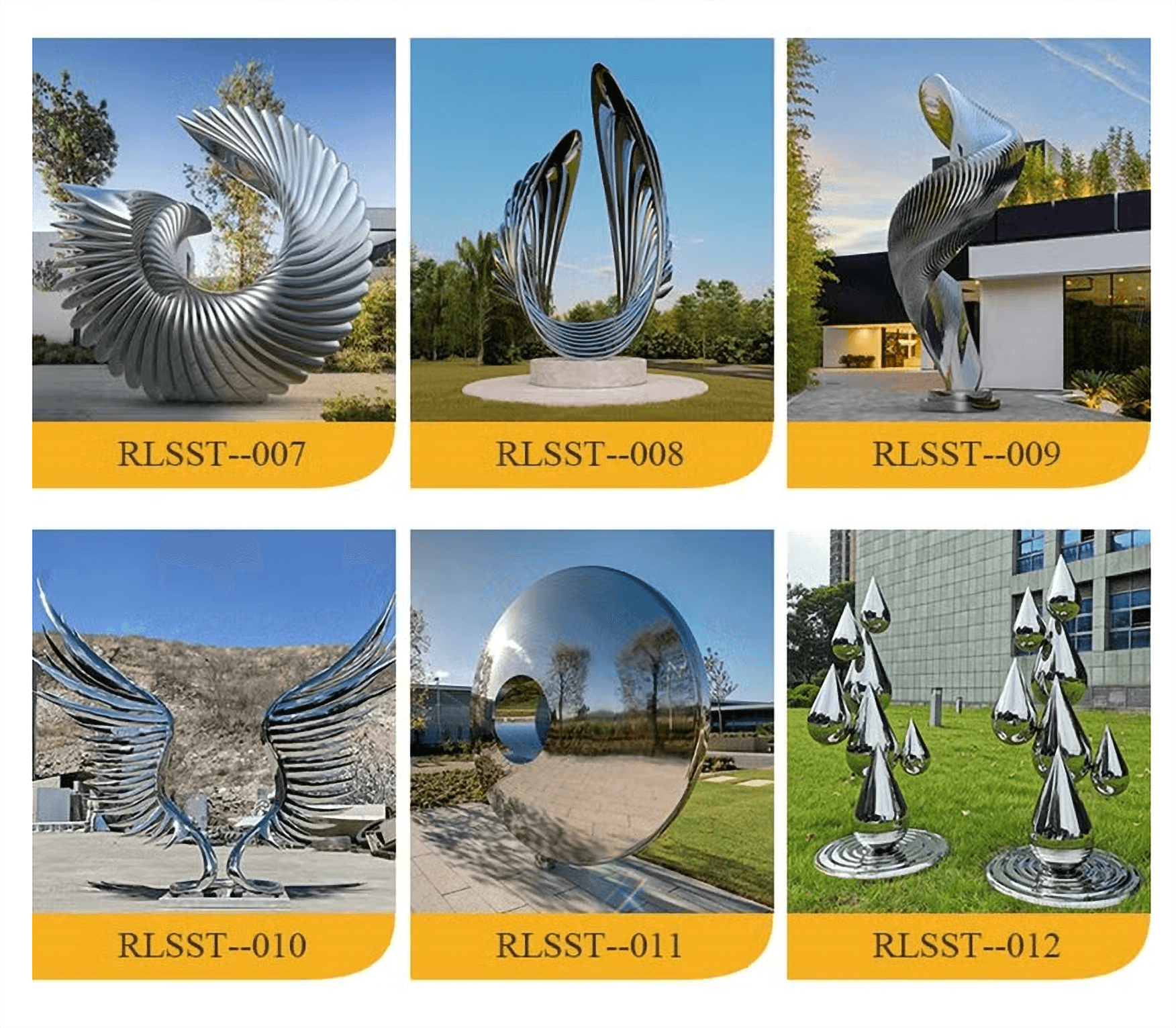

In the contemporary art system, the pursuit of originality has paradoxically produced a new orthodoxy: the predictability of the unexpected. The “perfect” artwork is not the one that takes risks, but the one that knows the code. Polished steel, marble, glass, hyper-smooth surfaces. Large scale, noble materials, sterile political allusions, highly photogenic installations. Every element is a clear signal to collectors, curators, and the public: “This is art. Here’s the visual pedigree you were expecting.”

It’s no longer art that builds its own language.

It’s the prepackaged language of art that chooses the works.

Too often we find ourselves writing about exactly this. But it’s not a polemical stance.

We’re fascinated by it.

We can’t help ourselves.

Each time we face it, we go a little deeper, because we feel that within that endless repetition of the same forms, the same concepts, the same materials, something bigger is at stake: the very relationship between imagination and system.

Repetition is not a disease, it’s a structure.

And when a structure becomes invisible, that’s when it’s time to look it in the eye.

Let’s think about it: what makes a work “strong”? What makes it feel “right” in an exhibition context, at a fair, on a white wall or in a foundation’s feed?

Most of the time, it’s not the content, not the gesture, not the vision.

It’s its ability to fit into an already legitimized form.

A work “works” because it resembles others that have already worked.

Because it sounds like something we’ve already heard.

Because it reassures.

In this sense, the “perfect form” is also a perfect container: it accommodates whatever is placed inside it, and makes it compatible with the context.

The work as a device of aesthetic consensus.

An elegant form to avoid conflict, not to disturb, not to disorient.

But if art is the place where we should be able to dismantle codes, not reinforce them, then something doesn’t add up.

The problem isn’t the use of polished steel.

The problem is when polished steel has become a category of thought.

When it is no longer a means, but a genre.

When it stops being a tool to say something, and becomes, in itself, the thing to say.

In this shift, a hidden mechanism is revealed: the art system, while claiming to reward vision, rupture, the unprecedented, in reality prefers stability. And it achieves this through a formalized, well-codified aesthetic, able to circulate through catalogues, collections, articles, awards.

An art that doesn’t make mistakes because it doesn’t take risks.

The result is that the “perfect” work, visually impeccable, conceptually comprehensible, logistically exportable, is also the most sterile.

Because it isn’t born of necessity, but of forecast.

But art, when it’s alive, is not predictable.

And what is predictable, no matter how smooth, is hardly still alive.

Strategies of Consensus

The question is no longer: What are you saying?

But rather: How well are you saying it in a language everyone already speaks?

In a system that is increasingly interconnected, observed, evaluated, and shared, art naturally tends to align with an aesthetic of consensus. It’s a Darwinian selection of form: what survives isn’t what’s most radical, but what’s most shareable.

Not what creates rupture, but what resembles rupture, while remaining compatible.

In this context, clichés become tools. They’re not just tired formulas, but functional shortcuts: they express recognizable, easily decoded concepts in a reassuring way.

A neon about trauma.

A marble block engraved with an aphorism on identity.

A printed face on fabric alluding to the invisibility of the self.

Everything works.

It works too well.

And if it works, it gets replicated.

And if it gets replicated, it becomes assimilated as “artistic language.”

And if it becomes language, it also becomes expectation.

And that’s where consensus is born: when the artwork anticipates the taste of its own audience.

What fascinates us is that this often happens unconsciously.

The artist doesn’t copy, doesn’t fake, doesn’t lie.

They simply internalize the code.

They become fluent in a language they never truly chose, but that allows them to exist within the system.

The curator does the same. So does the collector.

It’s an adaptive intelligence: art that knows where to be, how to present itself, how to behave in order to be read, understood, sold, awarded.

No explicit compromise is needed, it’s enough to lean into what “works.”

The paradox is that in this flawless functioning, art stops vibrating.

Everything is already anticipated.

The curatorial discourse, just like the artwork, plays into this dynamic.

In the statements, we read the same words, the same conceptual turns, the same references (Foucault, Derrida, Haraway).

But by constantly invoking bodies, memory, trauma, postcolonialism, algorithms, archives, we risk turning art into a reflection of a vocabulary already validated.

Not a space for creating new signs.

What happens when critique becomes liturgy?

When language is no longer tension, but protocol?

At that point, even the concept becomes a material: a noble, recognizable material, like marble.

But using new words isn’t enough to think in new ways, just as carving silicone doesn’t automatically make it contemporary sculpture.

The material of an artwork isn’t only physical: it’s also discursive.

And today, that material is almost always ready-made.

This creates a perfect ecosystem: elegant, solid.

But sealed.

A system where every work seems like a refined citation of another work.

Every text, a scholarly comment on another text.

Every gesture, a knowing reprise of a gesture already historicized.

So where, then, is the interruption?

Where is the short circuit?

Where is the possibility of saying something that hasn’t already been forecast?

Perhaps it’s precisely in this void, in this inability to exit the code, that a new urgency begins to take shape.

Because every system, in order to survive, needs what destabilizes it.

And today, more than ever, the art system seems to be in need of something that doesn’t work.

Don’t Trivialize the Trivial

Banality is a specter that haunts every level of symbolic production.

We fear it, ridicule it, avoid it, and yet, when we seek consensus, it’s exactly where we return.

Because banality is not a failure of communication: it’s its default condition.

It’s what holds a collective together.

It’s what makes the circulation of signs possible.

Every culture is built on repetitive structures.

Every language is, in itself, a network of habits.

Every gesture, every form, every word we recognize draws power precisely from having already been seen, already spoken, already experienced.

Banality is shared memory.

It’s useful conformity.

It’s an internalized cultural pattern.

When an artist turns to a familiar form, it doesn’t necessarily mean they’re avoiding risk: perhaps they’re trying to make themselves legible, to find their position, to carve a path through the undifferentiated mass of noise.

The problem, then, isn’t banality itself.

The problem is when banality is never broken.

When it becomes the only code.

When everything becomes familiar.

When the entire cultural system organizes itself around the idea of recognizability.

At that point, banality is no longer a tool, it’s a cage.

And there is nothing more dangerous than unrecognized banality.

Because banality, when disguised as novelty, becomes farce.

When presented as depth, it becomes ideology.

When rewarded as avant-garde, it becomes stagnation.

And yet, it’s precisely in that smooth, polished, intuitive surface, where everything is already known, that we can glimpse the beating heart of our social structure.

Banality is not the opposite of depth.

It’s what precedes it.

It’s the invisible background from which every truly radical act can emerge.

This is why, now more than ever, we need an art that isn’t afraid to stumble, to disturb, to not work.

An art that recognizes the codes, and then disables them.

That can use imperfection as an opening, not as a flaw.

That reclaims the possibility of not being immediately decipherable.

In a system built on adherence, perhaps the most courageous gesture is the one that refuses to reassure.

Not to provoke.

But to see again.

What if the problem is us?

We’ve built ourselves the perfect alibi:

talking about art that works too well,

just to keep it working.

Because the issue isn’t only in the work that refuses to take risks.

The issue lies with those who want it to be recognizable, legible,

compatible with their gaze.

The issue is us, too.

Me.

You.

Us, the ones who claim to want the new, the unsettling,

but only as long as it’s polished, intelligent, sophisticated, quotable.

As long as we can talk about it with ease.

When was the last time a work genuinely made us uncomfortable?

Not in a political sense.

Not because it “deals with difficult themes.”

But because we simply couldn’t understand it,

and resisted the urge to wrap it up in a sentence,

a category,

a clever comment?

Sometimes, in calling out the system’s sterility,

we build another kind of aesthetic:

that of elegant disillusionment.

The “we know how it works” aesthetic.

The self-awareness turned into commodity.

We write critical texts to decode the system.

But maybe it’s time we asked whether our texts

are becoming part of the system themselves.

We say we want art that breaks the consensus,

is it naïve to want something like that?

And if it ever really did,

would we even be able to recognize it?

Sometimes, we too want to feel at home in dissent.

A neat dissent. Articulate. Well-edited.

One that doesn’t really force us to shift position.

One that doesn’t take away our microphone.

So then?

Maybe the question isn’t:

“What should art do to break the code?”

But rather:

“What are we willing to lose, to let it break free?”

Are we willing to give up our authority as informed readers?

Willing to be bored, to not understand,

to have nothing clever to say?

Willing to sit in silence before a work that offers us nothing,

no symbols, no thesis, no references, no visual hook?

Maybe what we need now is a form of criticism

built from juxtapositions and fragments,

we speak in images, in figures,

like collaging newspaper clippings into giant puzzles.

A criticism that doesn’t produce interpretation,

but simply sits beside the work like a foreign body.

One that says only:

“It’s here. And I don’t know what to do with it.”

And finally…

We’d like to write a text that doesn’t work.

That doesn’t do its job.

And knowing it’s possible,

we try again, at least one more time.

Maybe that’s the real break today:

To remain where reading fails.

And maybe, if we stay there long enough,

something might start to happen.

fakewhale

Founded in 2021, Fakewhale advocates the digital art market's evolution. Viewing NFT technology as a container for art, and leveraging the expansive scope of digital culture, Fakewhale strives to shape a new ecosystem in which art and technology become the starting point, rather than the final destination.

You may also like

Fakewhale in dialogue with Markus Sworcik and René Stiegler

Markus Sworcik and René Stiegler, known collectively as StieglerSworcik, strive to translate the co

Generative Futures: Interactivity in a Post-Web3 World

Through a synergistic fusion of blockchain technology and advanced creative coding, generative art i

Banks Violette in Conversation with Jesse Draxler hosted by Fakewhale

Banks Violette is an American artist whose sculptures and installations mine the aesthetics of black