This Sculpture Doesn’t Exist: Matteo Rattini in Dialogue with Fakewhale

Matteo Rattini’s work stems from a radical intuition about the identity and life cycle of art images in the digital sphere. His practice intertwines critical observation of platforms, displaced authorship through artificial intelligence, and visibility as both an aesthetic and political condition. His 2020 project This sculpture doesn’t exist anticipated many of today’s conversations around generative art, using a personal dataset and automated publishing strategies to question our ability to recognise, value, and differentiate art within the endless flow of online content. We at Fakewhale had the pleasure of speaking with Matteo about these key intersections, exploring his methods, concepts, and the evolving landscape of digital aesthetics.

Fakewhale: This sculpture doesn’t exist emerged during a pivotal moment, the 2020 lockdown, and directly questioned how art circulates within digital platforms. What drove you, at that time, to build your own dataset and generate images that could so seamlessly blend into real-world art feeds?

Matteo Rattini: Even before the pandemic, digital platforms were silently mediating much of our daily experience, but it was the global rupture that suddenly exposed just how total the mediation had become. At that point, online platforms were globally reshaping not only our social interactions but also cultural production and aesthetic experiences. Spectators were suddenly turned into users and fed hundreds of images of artworks and installation views, with little control over what they were shown. While those images retained a spectral quality, always raising the question whether something essential was missing from the canonical aesthetic experience, they were also consumed in an unprecedented form, shaped by algorithmic recommendation systems. These algorithms, operating according to logics completely detached from the criteria historically used to evaluate art, chose on behalf of viewers what they would see, locking them into loops of homogeneous content based on prior behaviour.

Simultaneously, the rise of artificial intelligence, gaining popularity through websites like This Person Doesn’t Exist, marked the beginning of a profound shift in our relationship with images. It became clear to me that AI was the most fitting tool to investigate the nature of online aesthetic consumption and to render visible the standardising processes induced by algorithmic systems – a phenomenon that could only be explored through the very mechanisms shaping it.

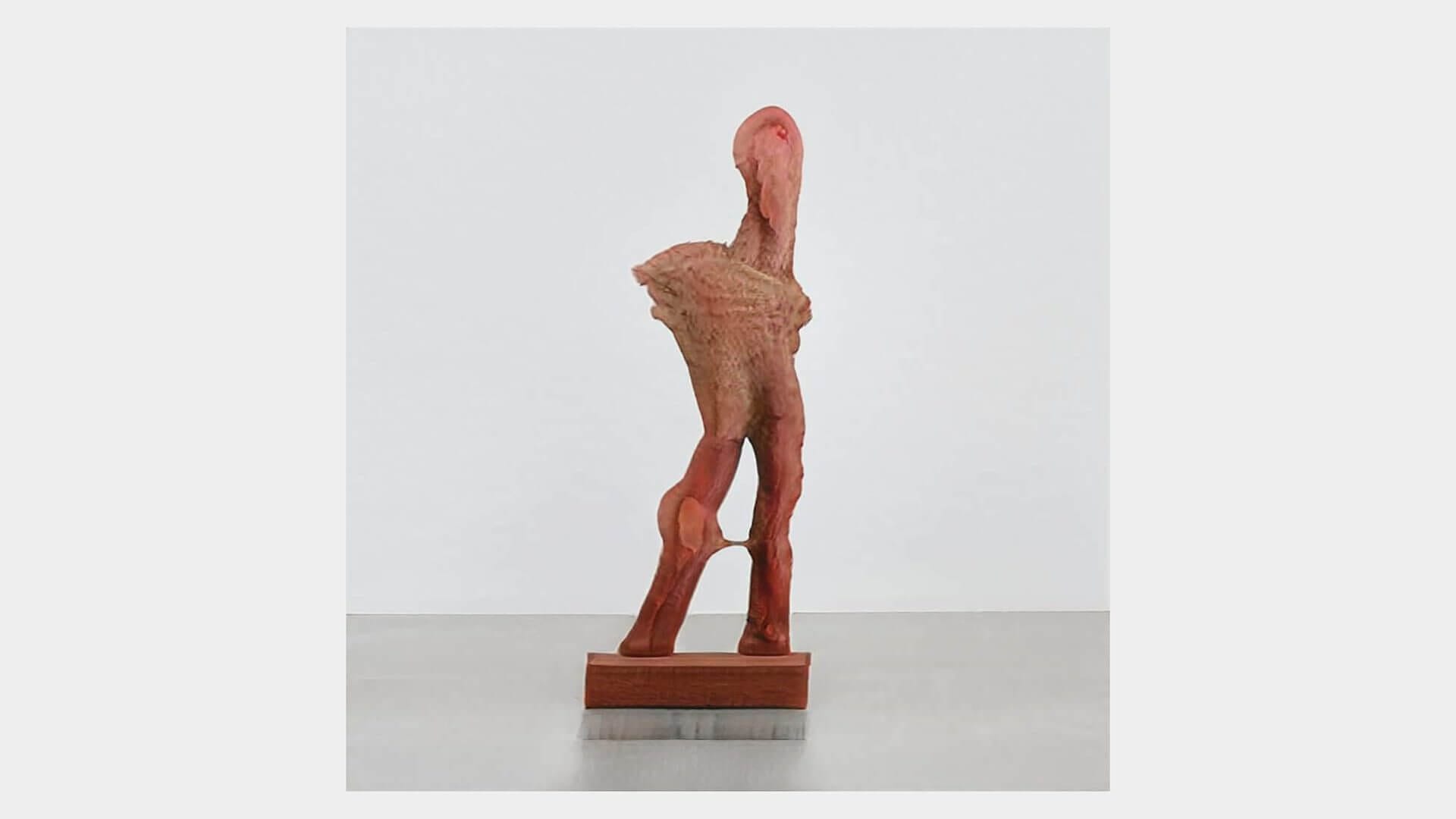

Over the course of a month, images that were being recommended as “contemporary art” by major image-sharing platforms were gathered and compiled into a dataset, then used to train a generative AI model. This model learned to produce images of artworks conforming to the styles and visual codes promoted on those platforms, resulting in abstract sculptures placed in sterile white cubes that could be inserted back in the flow of images, going completely unnoticed.

One of the most striking elements of the project is its lack of curatorial mediation: a generated image is posted every day to Instagram, entirely without human intervention. Why was it important for you to hand over that agency to the algorithm rather than retain control as the artist?

The initial data collection, the generation of the images and their distribution were highly automated. The more than 8,000 pictures collected, which seem trivial compared to the datasets used for large-scale models, were gathered from social media platforms using bots that automatically collected what was suggested to them. My intervention in the production phase was also minimal: I could only decide the number of seeds from which to generate images, as no other parameters could be modified at the time because of technical limitations. The generated images were then randomly chosen and posted on Instagram at set intervals.

The absence of artistic intervention was a spontaneous and almost necessary response to the logic of the systems I was working with: from social media algorithms to online bots and generative AI, everything seemed to demand to be left to operate autonomously. By avoiding any expected choice on my part, I was only embracing what I felt was a crucial change introduced by these technologies: a progressive loss of human centrality in both image-making and visual perception. The consequent aesthetic detachment I maintained toward the images produced was, for me, essential to suggest the ambiguous nature of these artefacts. Though they presented themselves as objects of aesthetic contemplation, they were actually statistical averages resulting from abstract processes of data analysis, compression and synthesis. With these images, traditional aesthetic categories felt meaningless: when you can generate thousands of them in just a few minutes, the symbolic fulcrum inevitably shifts away from the image’s surface to the systems and procedures that bring it into being.

The video installation version, shown in physical space, introduces a radically different sense of time: slow, fluid, nearly imperceptible. In your experience, how does this shift from online to offline change the way viewers engage with the work?

The problem with showing the work in an offline context was, in a way, how to render visible, or at least evoke, all the complexity that was fully present through its online fruition. With the video installation, I wanted to recreate the same sense of fixity that a still image of an artwork retains, along with the impression that something about that image was in a state of constant change, inevitably escaping the viewer. This is what led to the choice of an extremely slow video, a constant transition from one sculpture to the next, so slow that it was barely perceptible to someone looking at it directly, yet enough for the sculpture to have completely changed by the time the viewers walk past it again at the end of their visit. In a sense, it replicates the same relationship that generated images have with the latent space: while we perceive them as something fixed and finite, between each of them lies a complex, multidimensional space; a space where all possible variations and combinations are contained and organised, but that remains ultimately inaccessible to us.

In Captions, you created artworks that exist only through AI-generated textual descriptions. No image, only language and suggestion. What role does the viewer’s imagination play in this piece, and how does it speak to our oversaturated visual culture?

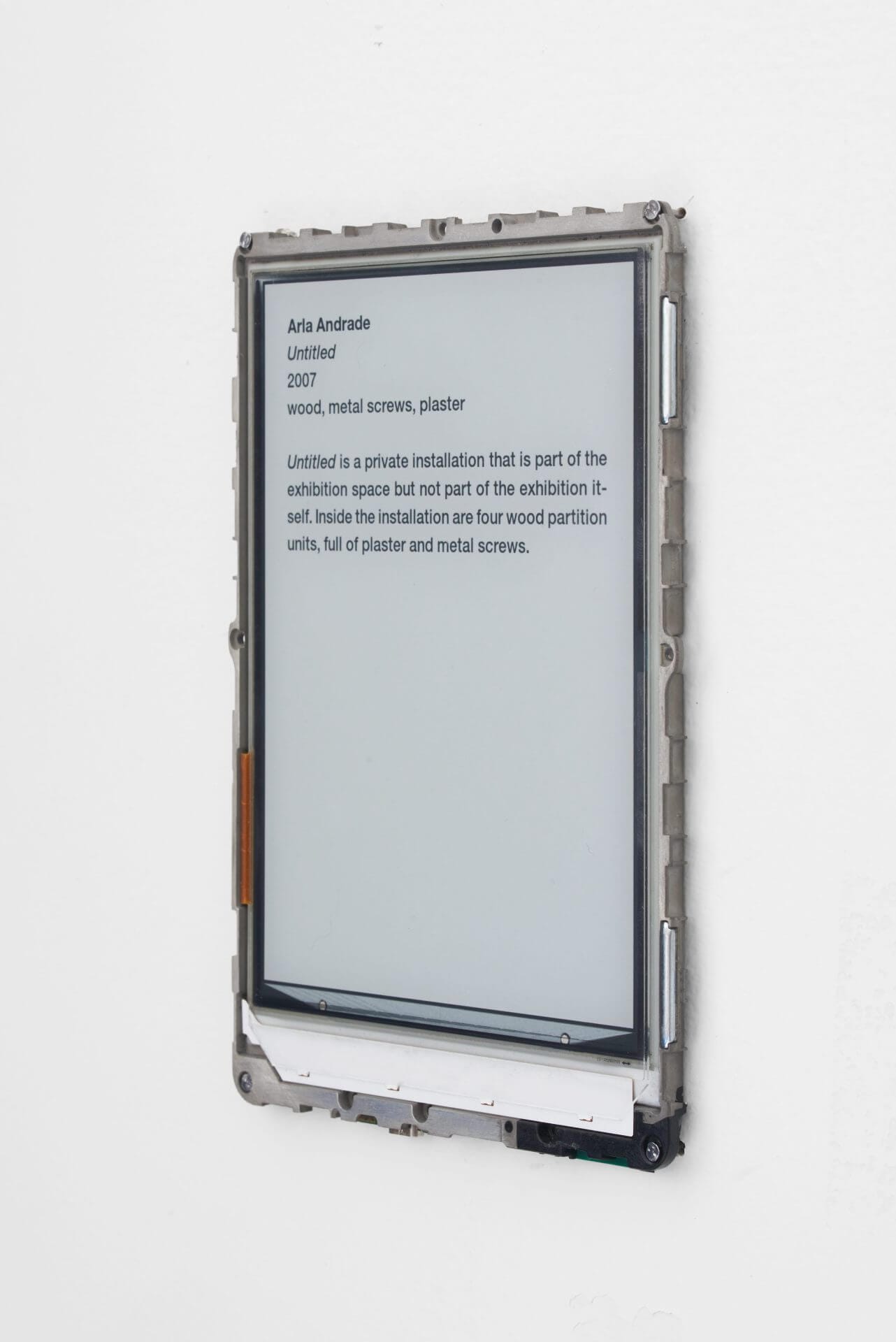

The work consists of a small e-ink screen, the size of a standard museum label, on which AI-generated captions appear one after another. All of them are produced using a custom dataset composed of textual material that typically surrounds works of art: museum labels, exhibition texts, and even audio guides for the visually impaired. The captions are completely disconnected from any actual object; they offer a plausible description of artworks with their materials, dimensions, and sometimes even their conceptual framework, but it’s up to the viewer to merge these fragments into a final mental image.

After the overabundance of the non-existent sculptures, which in their infinite combinations felt like they encompassed every imaginable possibility, I wanted to explore alternative ways of generating something, while keeping it withdrawn or even removed entirely from the visual sphere. By subtracting the central element – the image – what remained was a void that needed to be filled, and text appeared to me as the perfect replacement to fill this empty space without exhausting its possibilities. The generated descriptions were only vague hints that the viewer’s imagination had to pick up on, triggers that activated our capacity to generate dynamic mental images, shifting alongside the unfolding of the textual description. What I aimed to create was a convergence of generative processes: AI and text as aids for imagination, rather than tools for delivering a finished, ready-made outcome.

In works like Dataset, CCTV Sculpture, and I saw, you return to the idea of the dataset itself as both a conceptual material and a site of tension. Do you see the notion of art as “extractable material” as a fixed condition of working within algorithmic culture?

What I tried to do with these works was to carry forward the consequences of my earlier AI-based projects, keeping AI as a central point of reflection, but approaching it from a different perspective. With this intention, I became increasingly focused on the notion of datasets, along with related concepts such as digital archives and accumulation. I’ve always placed great importance on the role datasets play in shaping and determining both the output and meaning of the systems that rely on them. They are where generative models reside, the source they draw from and the material they return.

The work Dataset embodies this return to what comes before the generative model. It consists of a small screen that loops, at extremely high speed, through the thousands of images that make up the dataset used for This sculpture doesn’t exist. The images flash by so rapidly that they begin to blur into each other; the only stable elements are the white background and the grey floor, while the forms occupying the space start to merge and dissolve.

In the work I saw, I turned back to the process of building a dataset, this time through manual data scraping and accumulation, relocating those operations into the real world. Instead of relying on bots or scripts to extract data, I took on the repetitive, time-consuming task myself, keeping track of every artwork I saw in the span of a year, whether in person, in catalogues, online or on t-shirts, mugs, and billboards. The result was a list of over 12,000 items, forming a personal archive of experiences but at the same time a dataset that could theoretically be used to train an algorithm. The work was presented as wallpaper covering the walls of the exhibition space, creating a visual backdrop for the works installed in front of it.

CCTV Sculpture approaches accumulation from the opposite direction: not as variety, but as repetition. A single sculpture is recorded continuously by a surveillance camera in an anonymous setting. Like museum security systems, the gaze is fixed, automatic, and indifferent. The resulting footage, hours long and devoid of anything happening, is visible to the human eye but bearable only at a machinic scale.

All these works share, as a starting point, a preoccupation with the paradoxical transformation of artefacts into raw materials: extractable, accumulable, compressible, and transformable. On the one hand, art has become just another piece of content, mixed in with pictures of sunsets, newborns, or matcha lattes. On the other hand, the artwork itself has become a site of data extraction: through screens and platforms like Instagram, that measure how long we look at it; through museum cameras, that track which parts we focus on more, and also through its value, that has become an economic indicator of upturns or recession in the global market.

Throughout your practice, what kind of critical stance do you try to maintain toward artificial intelligence? Do you treat it as a neutral instrument, an ideological filter, or something more autonomous—perhaps even creative in its own right?

Artificial intelligence embodies a dense and unresolved field of implications. It is still in the process of being culturally, ethically, and aesthetically decoded while being simultaneously forced into every device and technology. Rather than viewing AI as neutral, ideological, or autonomous, I see it as inherently opaque: always suspended in an ambiguous zone where it oscillates between mere computation and intelligence, between a bias-spreader and analytical tool, between object and subject. The hype cycles around AI have pushed me away from the initial fascination with the tool itself. I find that such dynamics often reduce the depth of possible reflection, turning a complex cultural phenomenon into a spectacle of innovation. Through my recent projects, I’ve realised that what matters for me is not the technology itself but the cognitive, perceptual and cultural shifts it generates. What stays relevant even through rapid development is how it reconfigures our perception of the world, how it reorganises our experience, disrupts continuity, or renders certain aspects of reality invisible while bringing others into focus. In this sense, my gradual distancing from the direct use of AI doesn’t reflect a conceptual rejection, but rather an expansion, an attempt to explore fields that anticipated this new technology and the ones that are not yet fully permeated by it.

You mentioned feeling a strong affinity with the vision behind Fakewhale Studio. Could you tell us more about what specifically stood out to you in our work, and how you see these connections playing into your own artistic and conceptual framework?

I first encountered the works generated by Fakewhale Studio in the same way I wanted my own non-existent sculptures to be experienced: doom-scrolling on Instagram. Coming across your project reminded me, especially as I saw other creators exploring similar directions, that what we’re witnessing is less a matter of individual authorship and more a broader process of elaboration of the profound shift introduced by AI, particularly within the realm of art. This isn’t merely a technological adjustment; it’s a cultural and conceptual reorientation. In this light, it feels urgent to keep visible the essential questions raised by these ghostly, AI-generated works, while also preparing the ground to imagine forms of expression that may still be beyond our current grasp.

Looking ahead, are there any new projects you’re currently developing that continue your investigation into AI, language, and image perception? Or are you exploring new directions entirely in your artistic research?

Over the past few years, my research has gradually moved away from a direct engagement with AI and technology, shifting instead toward a broader reflection that moves between fixed dichotomies such as presence/absence, original/fake, and real/digital.

One area I’ve explored more deeply in the past year is that of forgery. After meeting a professional art forger, I began developing works inspired by his specific falsification techniques and his unconventional relationship with art. Forged artworks occupy a peculiar status: they appear to be art, but their legitimacy has been formally revoked. What remains in these ambiguous objects, stripped of their institutional recognition, are the circumstances of their production, the historical and cultural frameworks they attempt to infiltrate, their strategies of deception, and the ways they are eventually reabsorbed into other realms of life. I’m currently working on a series of works, each taking its steps form the primary traditional mediums such as painting, sculpture, photography and film, in an attempt to see what else these objects could be, once stripped of their status: expressionist paintings might end up being a serially produced home decor, fascist sculpture might become cupholders and souvenir photographs from the 1800’ might be used to smuggle illegal substances across borders.

What continues to be central in these new works, as with previous projects, is a deep concern with the expressive forms available to us today. In a world where we constantly navigate corporate-owned platforms and spaces, and consume mass-produced material and cultural goods, the tools we are given for expression are increasingly caught in mechanisms of homogenization. When every attempt at expression risks falling into prepackaged formats, practices such as appropriation, falsification, and deception appear to me as alternative ways to still say something.

fakewhale

Founded in 2021, Fakewhale advocates the digital art market's evolution. Viewing NFT technology as a container for art, and leveraging the expansive scope of digital culture, Fakewhale strives to shape a new ecosystem in which art and technology become the starting point, rather than the final destination.

You may also like

ArtVerse in Conversation with Fakewhale

Sebastien Borget has spent years shaping the digital landscape as co-founder of The Sandbox, one of

Jędrzej Bieńko, Kinga Dobosz, Agata Popik, Amelia Woroszył, Stress Hygiene at Przeciąg Gallery, Warsaw

Stress Hygiene by Jędrzej Bieńko, Kinga Dobosz, Agata Popik, Amelia Woroszył, curated by Katarzyn

KEN OKIISHI · JOHANNES PORSCH · TANJA WIDMANN: Derivatives Affaires at Schleuse, Vienna

KEN OKIISHI · JOHANNES PORSCH · TANJA WIDMANN: Derivatives Affaires at Schleuse, Vienna 05/09/2025