Wolfgang Tillmans at the BPI – Centre Pompidou, Paris

Wolfgang Tillmans, Nothing could have prepared us – Everything could have prepared us, 13 June – 22 September 2025, Bibliothèque publique d’information (BPI), Centre Pompidou, Paris, France

Some places feel less like they’ve been lived in and more like they’ve been dreamed backwards, each step already a fading memory. The Bibliothèque publique d’information at the Centre Pompidou is one of them. No library card is required here: just patience, a wait among queued-up bodies, minutes ticking by under a suspended light that has always felt both temporary and timeless. We came here to look for a book or a power socket, to escape the cold or to find a shard of concentration. But also to become part of a nameless, shared intimacy, the kind only certain public spaces can offer. Wolfgang Tillmans has chosen precisely this setting, the BPI, now about to close for five years, as the stage for his exhibition Nothing could have prepared us – Everything could have prepared us. And he’s done more than simply exhibit: he’s allowed the place to reveal itself for what it’s always been. An archive of presences.

Crossing the threshold of the BPI today means entering a space emptied out and reimagined: the once-crowded bookshelves and desks have been replaced by images, arranged not in hierarchy but in gravitational pull. It’s an absence that breathes. A horizontal maquette guides us into the exhibition, highlighting in lilac what remains, furniture selected by the artist, traces of time, fragments of purpose. Tillmans’ first move is to restore perspective to vision, in a space that usually drowns it.

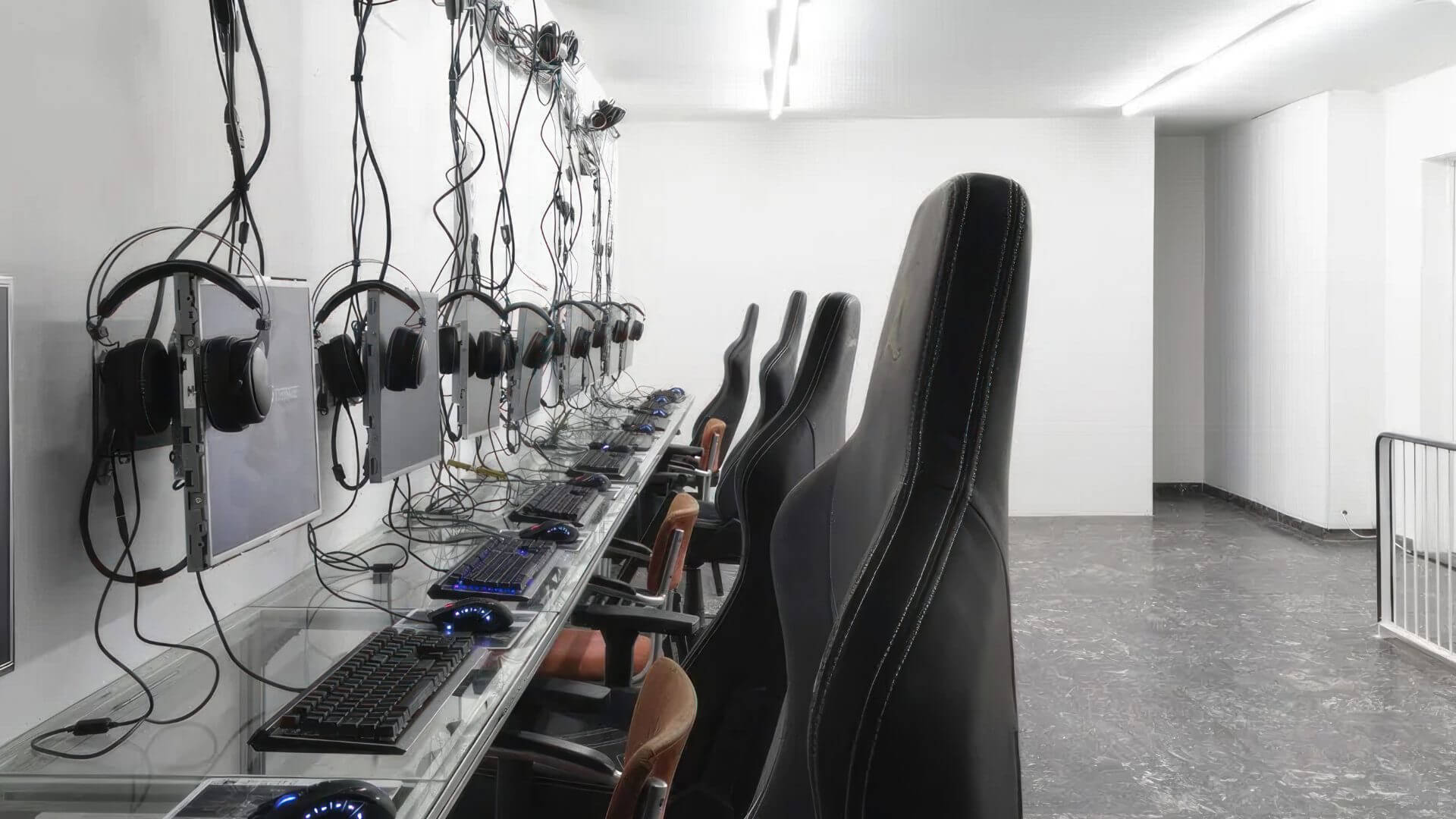

This exhibition holds a double memory: of the artist and of the site. At its core sits an installation made from the old self-training computer desks. On one side, a video library of Tillmans’ work; on the other, filmed portraits of BPI users. Though recently staged, the footage feels like relics: focused faces, stifled laughter, unaware glances. As if the artist sought to register the echo of a daily gesture before it disappears. The observer becomes the observed. The user becomes the image. And the library, once a container, becomes the subject.

As we move through the show, surviving pieces of furniture appear as bodies in metamorphosis. Two shelves, labeled “psychology” and “philosophy of ideas,” are nearly empty. Elsewhere, in place of books, we find artworks, magazines, personal archives. A ’90s copy of i-D is taped to the back of the information desk. The gesture is both tender and iconoclastic: objects once made for function now stand as aesthetic relics. Carpets in gray, green, and violet read like abstract paintings. Hanging signs, “Politics,” “Philosophy”, now drift directionless. The library dresses as a museum; the museum dissolves into a library.

There’s a methodical lightness in how Tillmans handles his materials: photos taped directly to the wall, wooden tables displaying his Truth Study Center, a curated chaos of images, clippings, texts. Initially, the layout feels almost didactic. Then it thickens, overlaps, dares us to undo every system. Time itself seems to fold: printed sheets suggest alternate chronologies, “2020 is as far from 1980 as 1980 is from 1940.” Space curls in on itself too: curled-up paper, falling sheets, mirrored surfaces reflecting the ceiling like an anatomical section.

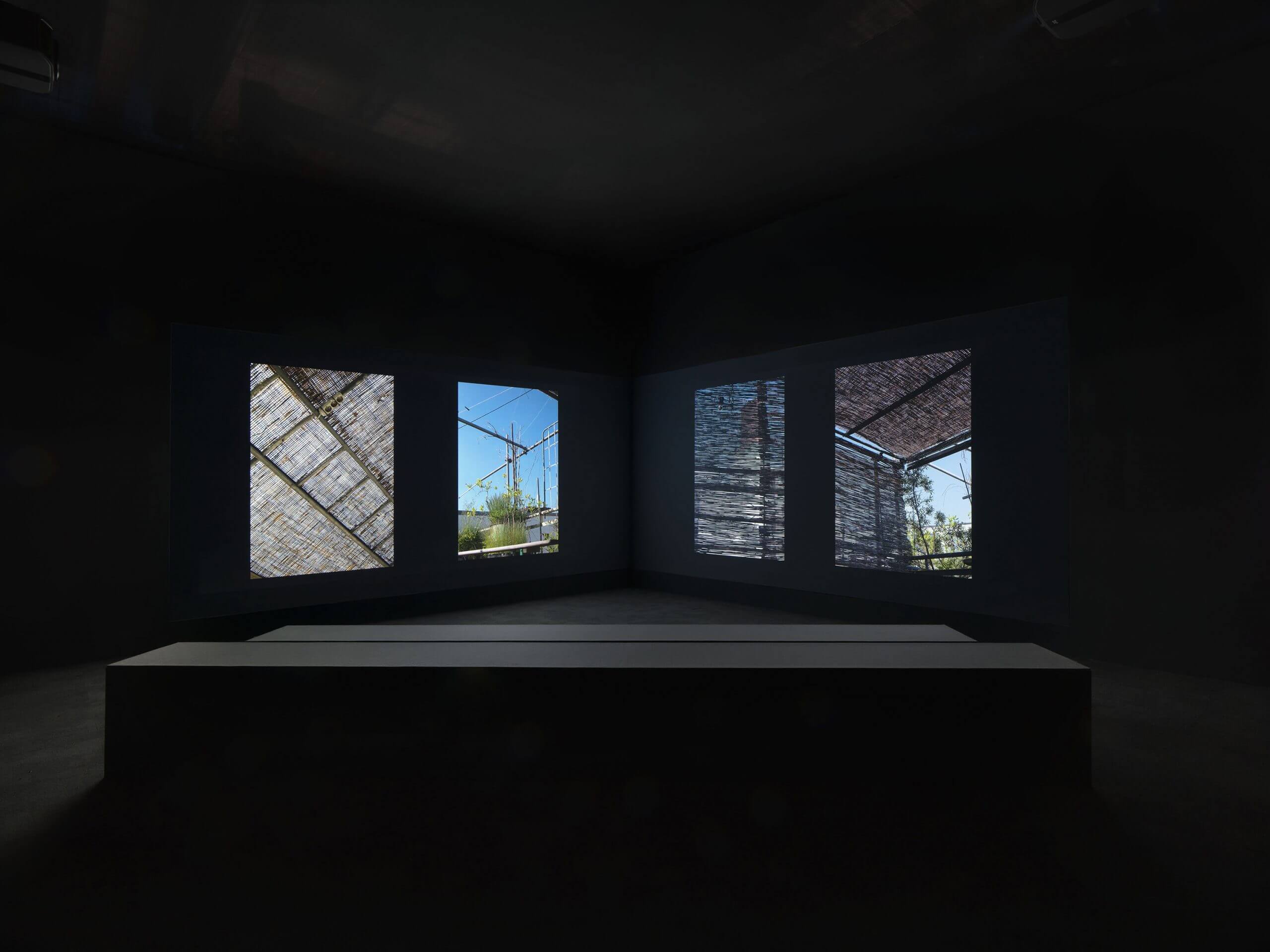

The sculptural climax arrives with tables transformed into visual altars. One, mirrored, reflects the Pompidou’s exposed frame; another, Roses de Nîmes, overlays a photograph of flowers with a glass pane that catches neon light from above, as though our gaze were photocopying reality. In the final room, shrouded in a silver curtain, we find ceiling scan, a laser installation that maps the building’s skeleton with floating, almost cosmic lines. We’re invited to lie down and look up, as if beneath a starry sky.

We leave the show a bit dazed. It felt less like a retrospective than a controlled implosion, not just of a building, but of an era. There is something encyclopedic here, yes, but in the sense of vertigo: the kind felt before the vastness of knowledge and imagery. Tillmans doesn’t offer synthesis but rather an exercise in attention. He asks us to move through, not to understand.

And so, as the BPI begins its temporary exile, perhaps what lingers is precisely this impossibility of retaining everything. Just a copy, a memory, a print. A friend told us the only bad thing about the exhibition was the postcards in the gift shop. We suggested they head back to the photocopy room.

fakewhale

Founded in 2021, Fakewhale advocates the digital art market's evolution. Viewing NFT technology as a container for art, and leveraging the expansive scope of digital culture, Fakewhale strives to shape a new ecosystem in which art and technology become the starting point, rather than the final destination.

You may also like

Fakewhale in conversation with Brennan Wojtyla

With LAN, Brennan Wojtyla transforms TICK TACK into an immersive installation that fuses gameplay, n

Theo Papandreopoulos, “CARNYX,” at Koppel Project – PAUSE/FRAME, London.

“CARNYX” by Theo Papandreopoulos, curated by SUNEND, at Koppel Project – PAUSE/FRA

Curating Tomorrow: Verse’s Vision for the Future of Contemporary Art

We are excited to announce that Fakewhale will be one of the selected galleries active in the Verse