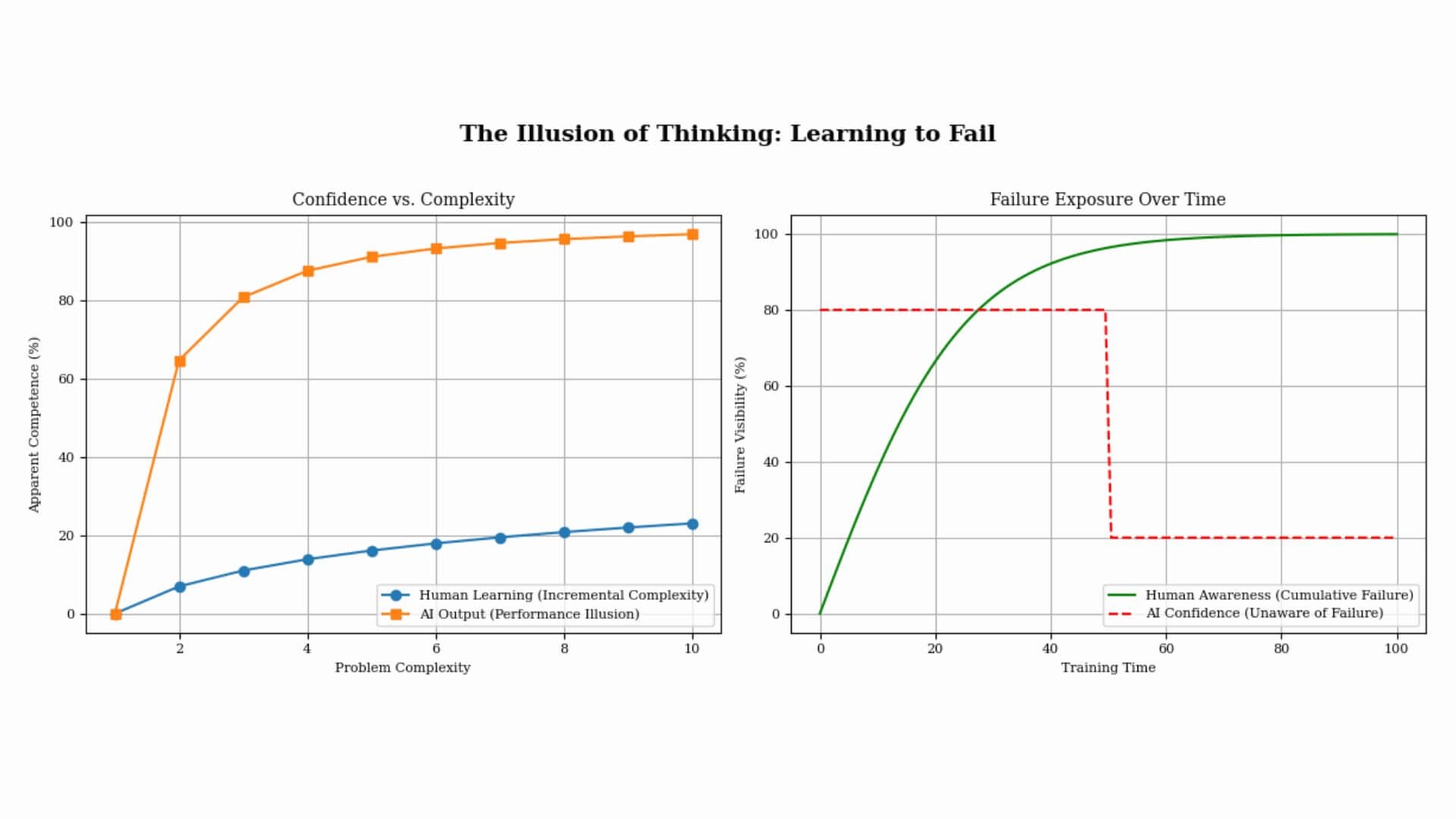

“The Illusion of Thinking”: Learning to Fail

A few days ago, we published The Illusion of Thinking, a speculative detournement of an Apple research paper on artificial reasoning. The operation was simple: we replaced the subject “AI” with “artwork,” revealing how the logic of simulation, optimization, and surface-level depth applies equally to certain modes of contemporary art-making. The resulting text was received not as parody, but as resonance. It gave language to an unease many had felt but not yet articulated, that some artworks, like some machines, no longer think. They perform the gesture of thinking. They appear to feel. But something beneath the surface remains inert.

In the days that followed, we encountered a different kind of response, one that did not stop at aesthetic simulation but pushed further, into the question of learning itself.

What if the real difference between machine and human, between artificial intelligence and artistic intelligence, is not one of output, but of failure?

What if complexity, in its deepest sense, cannot be generated by systems that are designed to succeed?

This article begins from that shift.

We no longer examine the simulation of depth, but the conditions under which depth emerges at all, and what is lost when those conditions are replaced by systems that reward only precision, fluency, and coherence.

The comparison with AI remains, but it moves to a new plane. This time, we are not asking whether machines can produce art that looks like thought. We are asking whether any system that cannot risk incoherence is capable of evolving.

In other words: what happens when failure, the slow, recursive, contradictory process by which humans learn, mutate, and create, is no longer part of the system?

What happens when even the gesture of error is formatted?

Learning to Fail is not a continuation of the previous text. It is a deviation.

A departure from aesthetic critique into ontological concern.

A return to the unresolved, the unstable, the illegible space in which intelligence, both artistic and cognitive, begins to form not in spite of failure, but because of it.

What follows is not a manifesto.

It is a proposition: that to think, to create, to make meaning in any real way, we must first recover the right to be wrong.

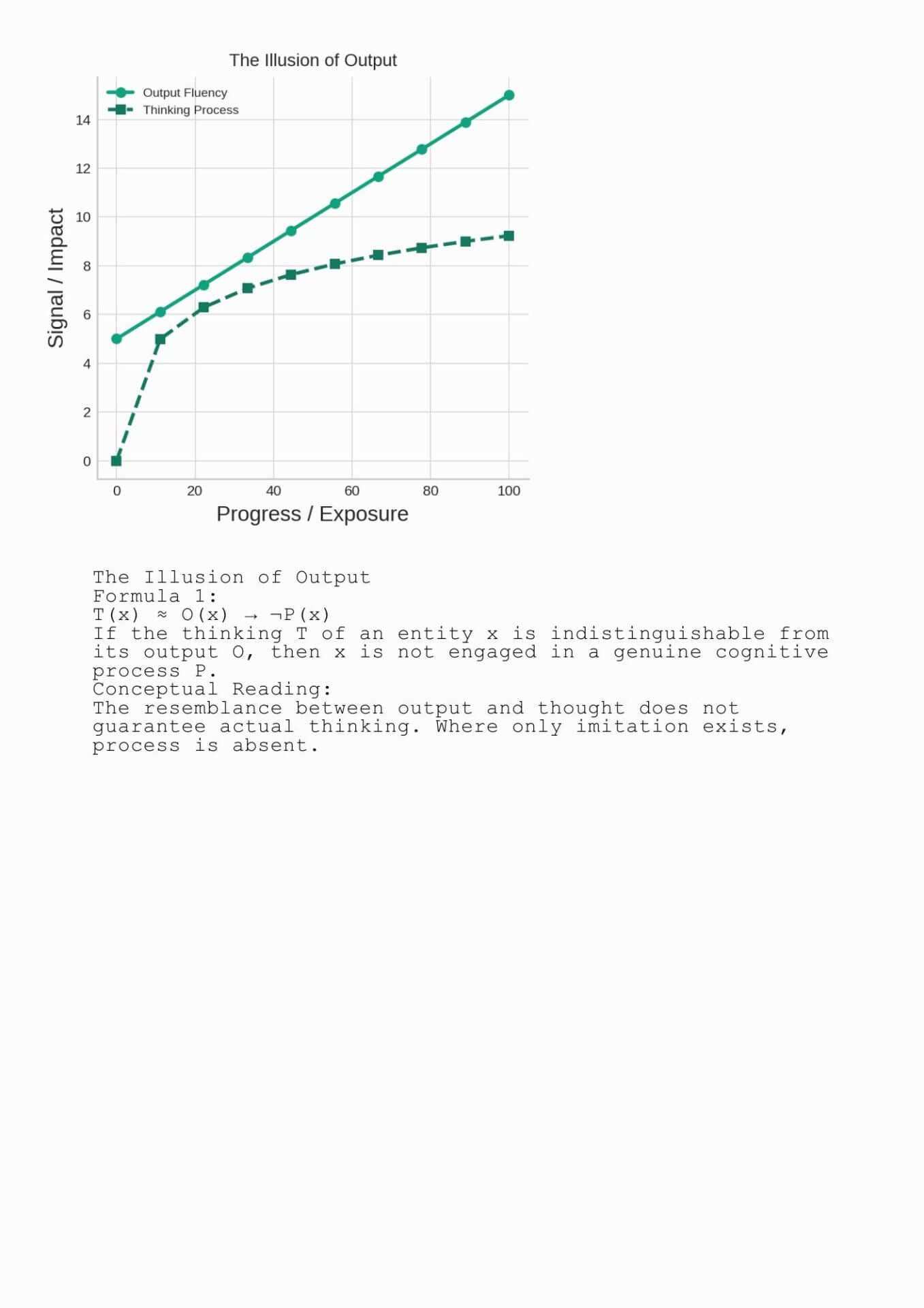

Some things look like thought.

They move like it, reference it, even echo its patterns, but they are not thinking.

They are output. Designed, refined, iterated. They give the impression of cognition, yet remain fundamentally exterior to the struggle that thinking requires.

This is the core confusion of our time: we mistake sophistication for consciousness, fluency for process, and the appearance of depth for its lived experience. We inhabit a landscape where the simulation of intelligence is no longer an aspiration but an operational standard, and where the capacity to produce “smart” output has become indistinguishable from the capacity to think.

But thinking is not output.

Thinking is not fast.

Thinking does not behave.

It falters, retracts, hesitates.

It unfolds over time, in contradiction with itself, and rarely arrives at clarity on the first attempt.

In fact, real thinking often resists legibility, it has to risk not knowing in order to produce something that was not already in circulation.

This is where art becomes relevant.

Not as a space to affirm what we already understand, but as a terrain in which something unprocessed, unresolved, raw, or unready, is given form before it is fully grasped. The artist, in this sense, does not always know what they are doing. And that’s the point.

Because it is precisely this exposure to uncertainty, this willingness to be wrong, that enables new forms of meaning to emerge.

The danger today is not that machines will replace artists.

It is that artists will begin to behave like machines, producing fluent, responsive, optimized content that performs the gesture of thought without ever undergoing it.

We’ve reached a point where it is no longer radical to be intelligent.

What is radical, perhaps, is to allow thinking to be incomplete.

To resist the pressure for resolution, and instead remain suspended in the discomfort of something that doesn’t yet know how to finish itself.

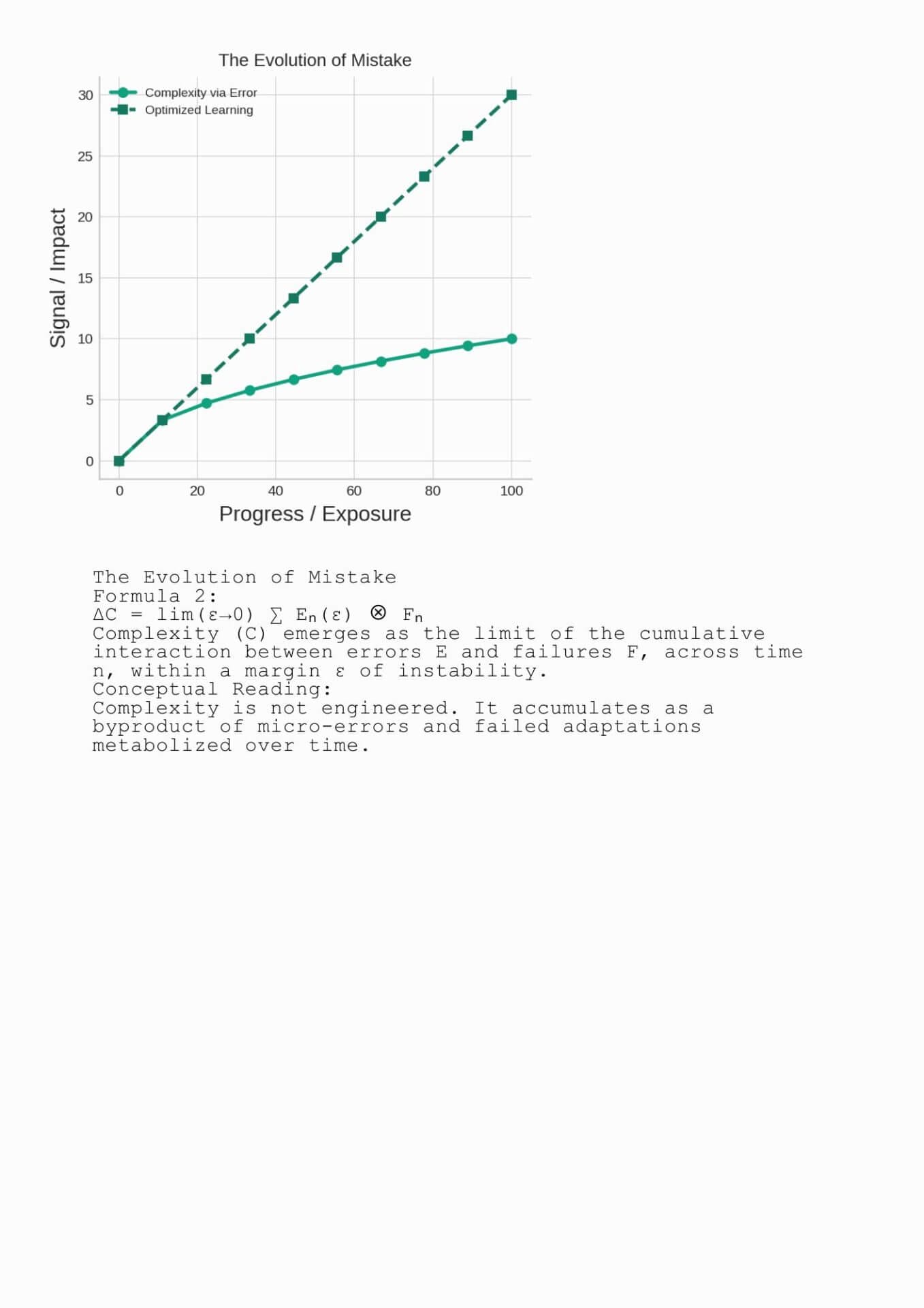

The Evolution of Mistake

Living systems evolve through failure.

Not failure as flaw, but failure as condition, as friction between intention and environment, between desire and limitation.

Complexity, in this sense, is not planned. It emerges. It accumulates through attempts that don’t fully succeed, through paths that collapse, through forms that adapt to conditions they cannot fully control.

Biological intelligence is built on this principle.

Every organism, from the simplest to the most intricate, develops in relation to its environment through cycles of disruption and repair. The nervous system doesn’t improve through perfect repetition. It improves by misfiring, by overreaching, by erring just enough to discover something new.

Mistake is not the opposite of learning, it is its prerequisite.

Artificial systems, by contrast, are constructed to optimize away from error.

Their progress depends on removing the unexpected, on tightening the loop between input and output until variation becomes manageable. The more efficient the machine, the less it tolerates deviation.

And while this produces astonishing results, speed, fluency, replication, it also eliminates the very thing that makes development truly complex: irreversible, unplanned deviation.

This is why simulated intelligence becomes predictable over time.

The system can surprise you once. Maybe twice. But not indefinitely.

Because its novelty is not emergent, it is preconfigured, drawn from a probability space that narrows the moment it is defined.

Human cognition, on the other hand, is shaped by what it cannot anticipate.

A child doesn’t learn to speak by perfect mimicry. They learn by breaking language, by trying and failing, by pushing against the syntax until a new rhythm is found.

This is not noise. It is structural innovation through deviation.

Art behaves in much the same way.

The most significant gestures in art history were often misunderstood when they emerged, because they broke with something unspoken, a formal consensus, a cultural rhythm, a representational contract. They failed to be recognized immediately, and that delay is what made them disruptive.

We forget this now, in a time when recognition is instant.

But without misalignment, there is no transformation.

And without the ability to fail in public, in process, in thought, we lose access to the forces that generate real complexity.

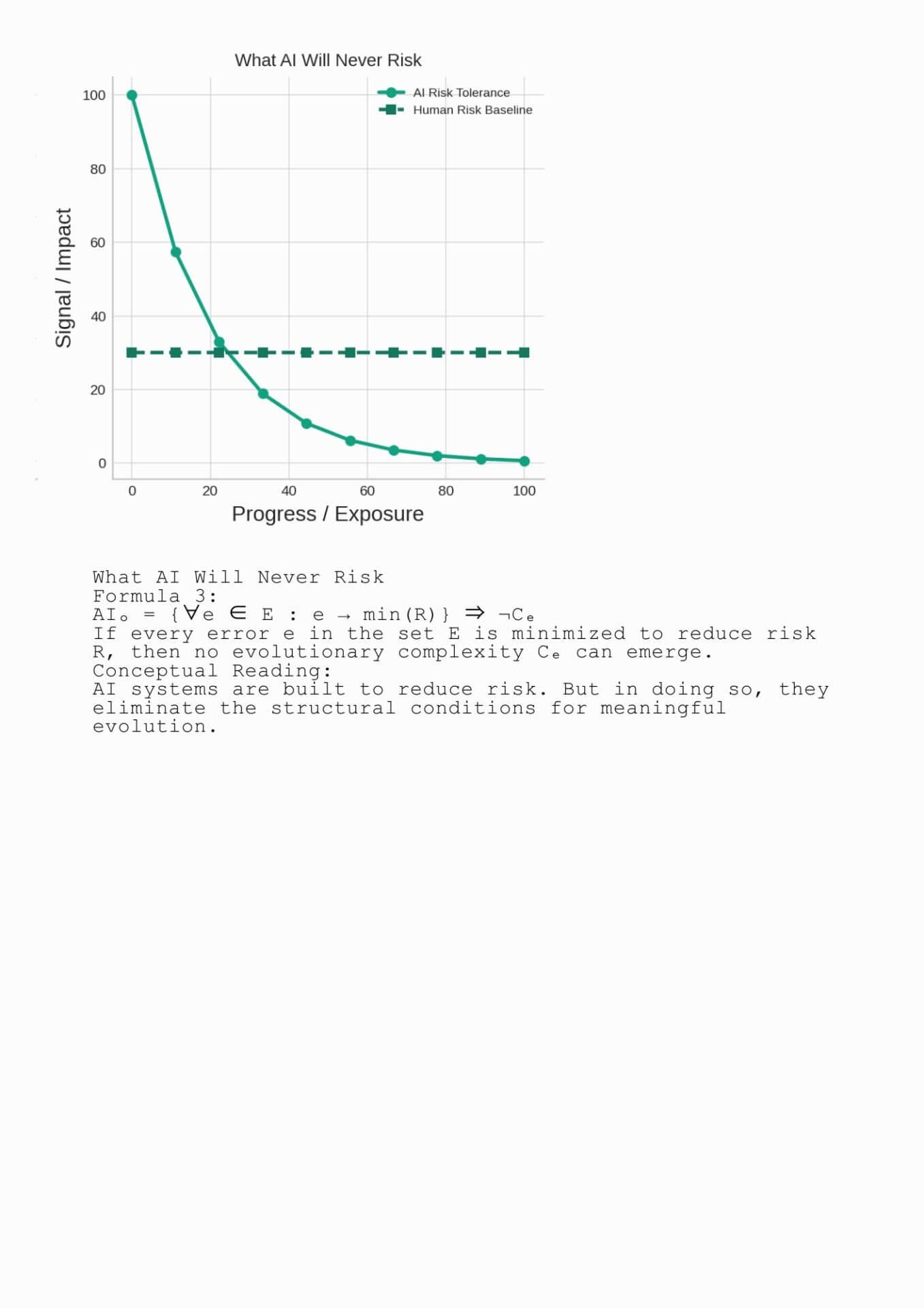

What AI Will Never Risk

Artificial intelligence does not risk anything.

It processes, it calculates, it approximates. But it does not commit.

Its decisions are not tethered to consequence, and its missteps are not endured, they are corrected, iterated, silently replaced by the next best guess. There is no memory of failure, only the constant refinement of prediction.

What this produces is not evolution. It is compression.

Each output is an attempt to reduce the space of uncertainty, to arrive faster, cleaner, more believably.

In doing so, AI generates an illusion of intelligence that gets more polished with time, but not more complex.

Because complexity, the real kind, requires the friction of exposure, the messiness of embodiment, the persistence of contradiction.

AI cannot afford contradiction.

Contradiction is inefficient.

It breaks the model, creates ambiguity, slows down the system.

So instead, the machine performs coherence. It arranges fragments in plausible sequences, producing text, images, voices that feel as though they emerge from thought, but in fact, they emerge from pattern density.

This is not a limitation in engineering terms. It’s a design feature.

These systems were never meant to think. They were meant to simulate the appearance of thought, fast, cheap, infinitely replicable.

The risk is that we forget the difference.

Because the more seamless these simulations become, the more we begin to recalibrate our sense of intelligence around recognizability.

Thought becomes what can be formatted.

Creativity becomes what circulates well.

Insight becomes what fits inside a caption, a prompt, a trend.

And so, while human intelligence stutters, contradicts, spirals, and resists conclusion, machine intelligence offers a smoother ride.

But the cost of smoothness is depth.

The cost of fluency is rupture.

And the cost of optimization is precisely what makes the work of thinking, and art, transformative.

AI will never risk misunderstanding itself.

It will never hesitate in a way that redefines its own process.

It will never produce a gesture it cannot recognize.

But art must.

Because every meaningful act of creation involves the possibility that it will not be legible, not now, not ever.

And that is what AI will never risk: to mean something that cannot yet be understood.

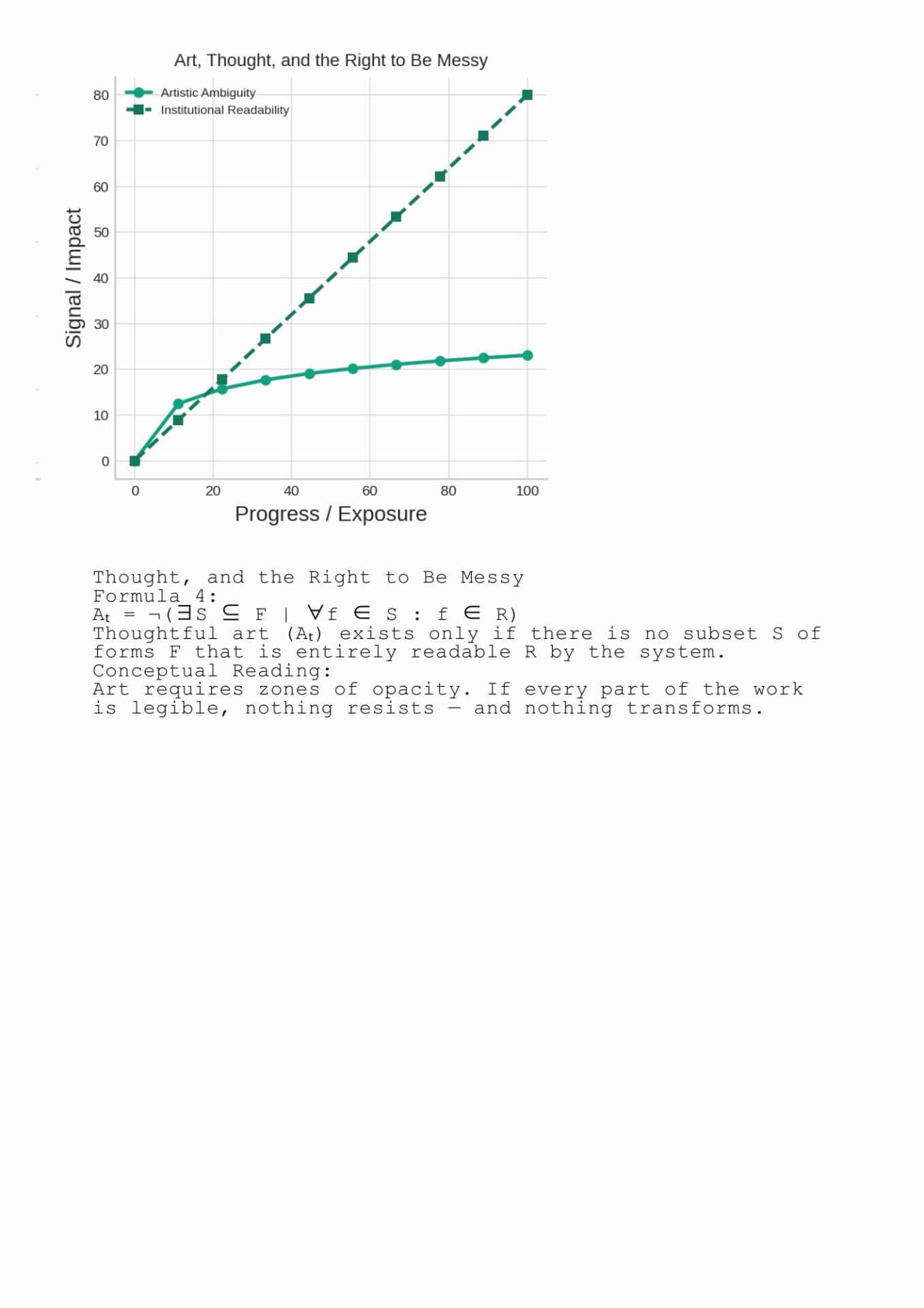

Art, Thought, and the Right to Be Messy

Art does not owe us clarity.

It does not exist to resolve meaning, nor to package experience into legible forms.

At its core, art is a site of friction, a space where thought encounters resistance, where sensation precedes language, where contradictions are not problems to be solved but conditions to be held.

To be an artist is to inhabit that space without guarantees.

To make something that might not work, might not land, might not be understood, and to remain faithful to it anyway.

This is not failure in the conventional sense.

It is ontological exposure: a willingness to act before knowing, to gesture before justifying, to commit to a form whose meaning will arrive, if at all, only later.

In contrast, simulated intelligence performs precision.

It presents images that align, texts that persuade, arguments that conclude.

Its power lies in its cleanliness, the way it removes noise, streamlines affect, and generates coherence at scale.

But art, when it matters, is not clean.

It is messy, unresolved, disruptive, not because it is unfinished, but because it refuses premature form.

There is a kind of intelligence that lives in disorder.

Not the chaos of randomness, but the productive chaos of a thought that hasn’t yet collapsed into style.

This is what the current cultural atmosphere tends to suppress: the right to stay in the not-yet, the discomfort of work that does not immediately signify.

We are increasingly conditioned to deliver polished outputs.

Even artists are expected to explain, to contextualize, to embed their work in familiar discourses.

But in doing so, something essential is lost: the illegibility that protects creation from being instantly reduced to content.

To think through art is not to design meaning.

It is to build forms that contain their own instability.

Forms that wobble, contradict themselves, resist finality, and in doing so, invite the viewer not into understanding, but into a shared state of not-knowing.

This is not a weakness. It is the essence of artistic thinking.

And it is precisely what simulation cannot replicate.

Because to simulate art is to anticipate its reception.

But to make art is to risk the fact that no one, including the artist, may fully grasp what it is, or why it needs to exist at all.

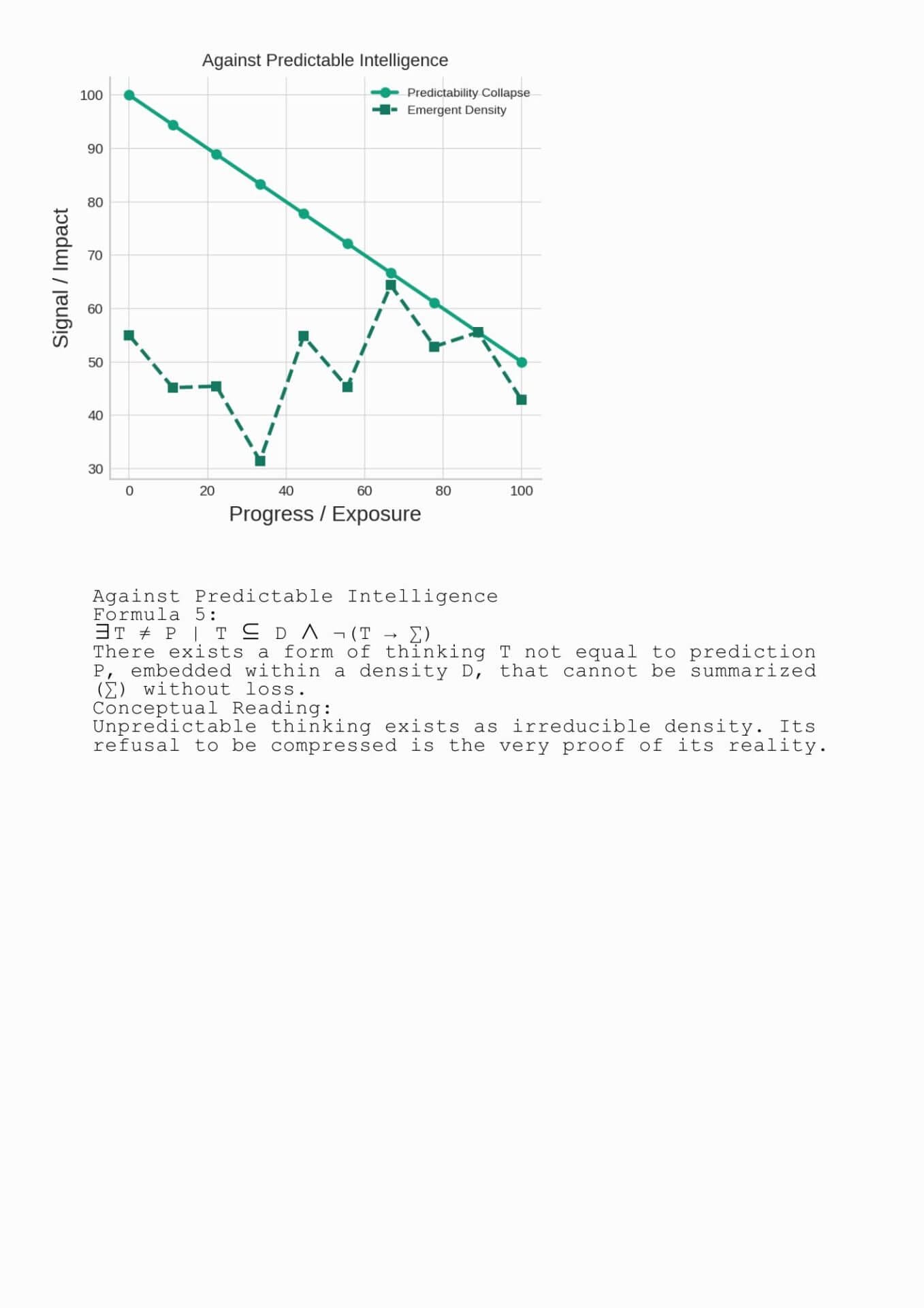

Against Predictable Intelligence

There is nothing radical about intelligence that always delivers.

Predictable intelligence reassures, flatters, completes our expectations. It simulates risk while quietly avoiding it.

It is the kind of thinking that already knows where it’s going, and makes sure you do too.

But real thinking does not unfold that way.

It stumbles, derails, loops back on itself.

It threatens the speaker, not just the listener.

And it produces not clarity but unsettlement, the sense that something has shifted in a way that cannot be immediately resolved.

In a culture increasingly shaped by algorithmic consistency and accelerated legibility, this kind of thinking has become rare, even suspect.

We’re trained to perform intelligence, to generate outputs that are clear, timely, contextualized.

But thought that matters often arrives too early or too late, outside the rhythm of visibility, beyond the frame of consensus.

To think in unpredictable ways, and to make work that reflects that unpredictability, is now an act of resistance.

Not resistance as rebellion, but as fidelity: to uncertainty, to contradiction, to the possibility that what we are making is not yet legible in the world as it stands.

This kind of fidelity cannot be optimized.

It cannot be turned into a prompt, a template, or a feature.

It exists in the refusal to finalize.

In the insistence that something might still be forming, not because it is weak, but because it is alive.

So perhaps the question is not how to make art in the age of AI.

But how to keep making art that doesn’t think like AI.

That doesn’t seek to persuade, impress, or predict.

But rather, invites us to think along with it, slowly, incompletely, and with the full awareness that whatever is emerging is still becoming itself.

Not faster.

Not cleaner.

But deeper.

fakewhale

Founded in 2021, Fakewhale advocates the digital art market's evolution. Viewing NFT technology as a container for art, and leveraging the expansive scope of digital culture, Fakewhale strives to shape a new ecosystem in which art and technology become the starting point, rather than the final destination.

You may also like

Etiene Crauss in Conversation with Fakewhale

Introducing Etiene Crauss Artist: Etiene Crauss – Living in: Brazil Visit Artist Website Etien

Longlife, Andréa Spartà

Longlife, Andréa Spartà, curated by Maëlle Dault, Frac Île de France Andréa Spartà’s dis

Fakewhale in Conversation with Martin Dörr: Sleepwalking Systems

We have been closely following Martin Dörr’s interdisciplinary practice, which weaves together in