Joan Jonas: The Mirror Was the First Screen

Beginnings in Reflection: The Birth of a Language

In the 1960s, New York was a magnetic field of colliding languages: postmodern dance, performance, conceptual art, minimalism.

It was in this context that Joan Jonas, born in 1936, began her artistic exploration, one of the first artists to understand that performance was not merely an ephemeral gesture, but a form of embodied thought.

Her background, balanced between theater and sculpture, allowed her to move freely across disciplines without feeling their boundaries. From the very beginning, Jonas conceived of space as an extension of the body, and of the body as a surface of translation.

In an era still dominated by the male gaze, her approach stood out for its radical attention to perception: not so much what is seen, but how it is seen. Her art was never meant to be simply observed, but to create situations of reflection, in which the audience becomes an integral part of the work.

In her SoHo studio, then a semi-abandoned warehouse turned collective laboratory, Jonas began to build a language grounded in the body’s direct experience of space. She worked with mirrors, plexiglass, repeated gestures, visual rhythms. Each element became a way to explore the relationship between subject and image.

It was in this fertile ground that her vision took shape: an art that does not represent, but reflects; that does not describe, but dislocates.

Her work does not seek to fix a truth, but to suspend it, to make it perceptible in its fragility.

From the beginning, Jonas moved like a radar: capturing, amplifying, reorganizing. For her, art is a device of collective perception, a way to shift the center of vision, to show reality as something that can always change position.

Even before picking up a video camera, Jonas had already understood that the real revolution would not be technological, but perceptual.

Her early works, such as her mirror performances and actions in urban space, anticipated the reflection that would run throughout her career: the instability of the image and the impossibility of possessing a single point of view.

In reflection, everything is simultaneous.

And from that fragile, multiplied surface, the story of video art begins.

Mirror Piece and the Shattered Image

When Joan Jonas first presented Mirror Piece I in 1969, she was not simply performing a piece; she was founding a new visual grammar.

A group of performers, women and men, move through space carrying large mirrors in front of them. They lift them, tilt them, shift them. The audience sees itself reflected, fragmented, dissolved. The work becomes a perceptual ritual that turns space into an unstable threshold, where the viewer is both part of the scene and excluded from it at the same time.

With Mirror Piece II (1970), Jonas refines the structure: the mirrors grow larger, the movements more choreographic, the gestures more precise. But what truly changes is the awareness of the device itself. The mirrors are not symbolic objects; they are cognitive instruments.

Through them, the artist dismantles our trust in direct perception: what we believe we see is always a projection, a surface that returns our own image, slightly distorted.

It is a moment of rupture in the history of art. Until then, the image had been understood as representation, something that stands ‘in front of’ the viewer. With Jonas, it becomes a force that engulfs them.

Reflection becomes participation. The image becomes an event.

In the context of 1969, Mirror Piece also resonates as a political gesture: an act of reclaiming the gaze at a time when women were beginning to assert the right to be subjects rather than objects of the image. Jonas uses reflection as a blade, not to show herself, but to question the very act of seeing.

The audience, mirrored in the work, becomes aware of its own role within the space of representation: to look also means to be looked at.

Today, the work reads like a premonition.

Jonas’s mirrors and plexiglass panels anticipate our screens: surfaces that both reflect and filter, that connect and isolate.

In Mirror Piece, the image is no longer a window but a loop, a perceptual circuit in which subject and object continuously exchange positions.

It marks the beginning of the logic of the contemporary screen, the same logic that defines our relationship with digital devices and artificial intelligence.

The image of the self, multiplied and recomposed, becomes the very material of the work.

And the artist, like a programmer before her time, builds the first code of perception: a language made of reflections, fragments, and returns.

Between Performance and Video: The Body Becomes Signal

In the early 1970s, Joan Jonas crossed a decisive threshold: from the tangible matter of the mirror to the electronic light of video. Her language, already rooted in the body and in performance, encountered technology in a way that was never merely technical but deeply ontological. For Jonas, video was not a tool of documentation but a perceptual extension, a new skin of the image.

The year 1972 marked the birth of Vertical Roll, one of the most emblematic works of her career. In it, Jonas used a technical defect, the vertical roll of the signal, as a structural element. The image appears as an unstable flow, a rhythmic pulse that fragments the artist’s face into almost percussive sequences. Each vertical shift is a rupture in visual continuity, a beat measuring the very time of perception.

Jonas, reflected in this flux, becomes at once subject and object, flesh and signal, body and code.

This moment represents a turning point in the history of video art. Unlike other pioneers such as Nam June Paik or Bruce Nauman, Jonas did not seek to explore technology as an autonomous language but as an inner medium. Video does not separate her from the body; it translates it. It is a new form of dance, where gesture becomes image, and image, in turn, becomes memory.

In the early 1970s, Jonas worked on two simultaneous planes: the performative, ephemeral, shared, unrepeatable, and the medial, recorded, reproducible, suspended in time. This tension generated a new language, one that united direct experience with its technological reflection. In Organic Honey’s Visual Telepathy (1972), the artist created an alter ego, ‘Organic Honey’, an artificial female figure projected and duplicated across screens and mirrors.

Through this figure, Jonas explored identity as construction, as a performance of the self mediated by systems of representation.

The notion of telepathy in the title is not accidental: it alludes to a mode of communication that transcends speech and physical presence. Like telepathy, video allows one to be elsewhere while remaining here. It is a form of sensory ubiquity, a threshold between the intimate and the mediated, between consciousness and its projection.

In this sense, Jonas anticipated by decades the digital paradigm and contemporary virtuality: the body as interface, the image as a state of consciousness.

Her research evolved in a context where the first generation of video artists was still defining the rules of the medium. But Jonas did not aim to codify; she aimed to dematerialize.

Her video works, often shot in domestic spaces or natural environments, oscillate between ritual and experiment: repeated gestures, ambient sounds, live manipulations. Everything is precarious, unstable, yet it is precisely in this instability that her language finds its power.

Video becomes a dynamic mirror, a space where the body is no longer represented but processed.

In the following years, Jonas became part of the pioneering circuits of video art, exhibitions at Leo Castelli Gallery, performances at The Kitchen, encounters with artists such as Yvonne Rainer, Richard Serra, and Simone Forti. That network of artists and performers built the genealogy of a new art form that moved between body, image, and time.

In 1976, with Songdelay, Jonas brought her research outdoors: a performance filmed in an urban landscape where sound and movement are desynchronized, like visual echoes. The city becomes a mental stage, a spatial grid traversed by bodily signals.

During this period, the artist also developed a subtle but profound political awareness: the use of the female body as a field of inquiry and liberation. In her videos, the female figure is no longer the object of the gaze but the subject generating vision.

Jonas never proclaimed a feminist manifesto, but she embodied one in her method: every work is an act of perceptual autonomy, a gesture that restores to women control over image, rhythm, and presence.

With the transition to video, Jonas introduced into art history a new idea of authorship: no longer the creator of objects, but the builder of perceptual systems. Her work became a continuous dialogue between medium and memory, where every reflection is an act of knowledge.

For her, the camera is never a spectator but a participant, an eye that translates reality into a flow of signs.

Between performance and video, the body becomes signal.

With this intuition, Jonas opened one of the most fertile trajectories of contemporary art: the one that understands the image not as a representation of the world, but as an experience of thought.

Myth, Feminism and the Expanded Image

In the 1980s, Joan Jonas’s work entered a new phase of expansion: performance and video intertwined with narrative, myth, and the language of drawing. This transition marked the maturity of her research, from the body as a vehicle of perception to the body as an archive of stories.

The artist did not abandon the experimental tension of the previous decade but redirected it toward a more symbolic and literary dimension, transforming her practice into a territory of reflection on collective imagination and the construction of memory.

After the fragmented, pulsating experiments of the 1970s, Jonas began to incorporate complex narrative materials into her works, drawn from ancient myths, theatrical texts, and folk legends. Her use of myth is never illustrative; it is a form of translation, a way of decoding contemporary reality through universal archetypes.

In works such as Volcano Saga (1985–89), inspired by medieval Icelandic sagas, Jonas overlays the mythical figure with that of the artist, the epic with the intimate, the ancient tale with contemporary technology.

Narration unfolds as a layering of planes, video images, drawings, voice, music, performance, forming a visual and sonic fabric where myth becomes a living organism, continuously reinterpreted.

In the following decade, with Lines in the Sand (2002), Jonas drew on Gertrude Stein’s The Making of Americans and the poetry of H.D. to build a dramaturgy of female identity through symbols and gestures that cross time and culture.

The mythic arena becomes a map of feminist and linguistic coordinates, where the body is no longer a mere representation but an instrument for reading the world.

Jonas uses myth to speak of the present, and the present to give voice back to myth.

Her visual methodology expanded to include drawings, objects, ephemeral sets, and simultaneous projections. The performances evolved into complex perceptual environments where the boundaries between image and space dissolved.

In Jonas’s universe, everything communicates: the graphite line on the wall, the voice layered over ambient sound, the filmed figure interacting with the live one.

It is a form of ‘expanded image’, one that no longer belongs to a single medium but to the continuum between presence, time, and memory.

At the same time, feminist reflection took on a subtler and more philosophical dimension. Jonas does not engage through declaration but through the construction of a language that resists the patriarchal structure of vision.

Her works do not oppose the male tradition; they disarticulate it from within, dissolving the hierarchies of representation.

The woman is no longer the object of vision but the subject that produces vision, who reflects, narrates, and reinterprets.

In her work, female identity is a prism containing multiple forms: body, voice, image, specter.

The act of drawing, of tracing lines in space or in sand, becomes a symbolic foundation, an alternative form of writing that unites memory and intuition.

In The Shape, The Scent, The Feel of Things (2004), Jonas pushed her language even further, drawing inspiration from Aby Warburg and his idea of ‘Nachleben’, the survival of images.

She embraced myth as a tool for exploring the persistence of gestures and forms throughout history. Her performances became moving diagrams, where past and present reflect one another like two mirrored surfaces.

In this sense, Jonas continued the inquiry begun with Mirror Piece: reflection is no longer only optical but also cultural and temporal.

Her use of live drawing, introduced in her performances of the 2000s, represents a return to manual expression as a primary language, an extension of corporeality into the visual dimension.

For Jonas, drawing means thinking through the line, recovering the physicality of the mark in the age of digital reproducibility.

Each line traced during a performance is a memory taking shape before the viewer’s eyes, a writing of presence.

In this mature phase, Jonas becomes a kind of ‘priestess of vision’: her works do not seek to explain but to evoke.

Through the fusion of video, performance, sound, and drawing, she constructs a language that is at once poetic and structural, intimate and cosmic.

Her images do not represent the world; they reactivate it, they make it vibrate.

Every gesture, every reflection, every echo of sound becomes a window onto an expanded time, where the body is memory and memory is matter.

With Myth, Feminism and the Expanded Image, Joan Jonas defines an aesthetics of return and resonance, in which history is never concluded but continuously rewritten through artistic gesture.

Her works do not ask to be understood but to be experienced: they are acts of perceptual transformation, invitations to a deep listening of the visible.

Reflections for a Digital Age

In the present time, Joan Jonas’s work reveals itself with prophetic clarity. The reflective surfaces that in the 1960s questioned the viewer’s perception have now become the very landscape we inhabit: screens, video streams, digital windows, cameras, images that constantly reflect us without ever fully returning us to ourselves.

In this context, Mirror Piece is not merely a historical testimony to the birth of video art, but a conceptual device that continues to act, a matrix through which to read the contemporary condition of vision.

The logic of reflection that Jonas staged in 1969 anticipated that of algorithmic self-perception, a gaze that turns back on itself in an endless cycle of recognition and loss.

In her performances, the audience suddenly found itself included in the image, caught within a system of exchanges where it was no longer possible to distinguish who observes and who is observed.

Today, that condition has become the norm of digital experience, the self as interface, vision as involuntary participation in a shared field of data.

Decades in advance, Jonas understood that every visual technology, from the mirror to video, from the screen to the smartphone, is also a technology of subjectivity.

To look means to redefine oneself continuously through what the image returns.

Her work, therefore, does not belong to the past of video art, but to the future of perception, a future we now inhabit, often without realizing it.

In an age in which vision is mediated by artificial intelligence, filters, predictive algorithms, and systems of visual surveillance, Mirror Piece regains its full urgency. The mirrors and plexiglass panels used by Jonas can be read as early metaphors of the contemporary interface, surfaces that reflect, record, and distort, but never return a whole image.

In the reflected fragment, Jonas invites us to recognize the precariousness of our visual identity: what we see is always a construction, a momentary projection of our passage through the world.

Her later works, from the Lines in the Sand series to Moving Off the Land (2018), expand this vision to an ecological and planetary level.

Reflection is no longer only human, it becomes a natural dynamic, a continuous exchange between organism and environment, between vision and time.

The sea, water, animals, the sounds of nature, all become reflective surfaces, living memories of our gaze.

In Jonas’s work, perception is never an isolated act but a collective system, an ecosystem of images that observe one another.

For this reason, her art continues to speak directly to the language of the digital age and to the consciousness shaped by artificial intelligence.

Mirror Piece can be read as an archetype of the visual loop, a continuous flow of images that return fragments of ourselves, generating both reflective awareness and alienation.

What Jonas once explored as perceptual instability has now become ontological instability.

We have entered her mirror and can no longer step outside it.

Yet within this condition of infinite multiplication, Joan Jonas’s work preserves an irreducible delicacy: the artist’s gesture remains human, fragile, imperfect, a sign of presence in a world of automatic reflections.

Her practice, rooted in the slowness of the body and the concreteness of gesture, reminds us that the image is not only a code but an encounter.

Every reflection, even the most distorted one, still contains the possibility of dialogue, of a consciousness recognizing itself in its own dissolution.

In the silence of her performances, Jonas offers a lesson that feels more relevant than ever:

vision is not a technological fact, but an act of relation.

And in that act, mediated, projected, and reflected, lies our enduring capacity to remain present, despite everything, within the image.

fakewhale

Founded in 2021, Fakewhale advocates the digital art market's evolution. Viewing NFT technology as a container for art, and leveraging the expansive scope of digital culture, Fakewhale strives to shape a new ecosystem in which art and technology become the starting point, rather than the final destination.

You may also like

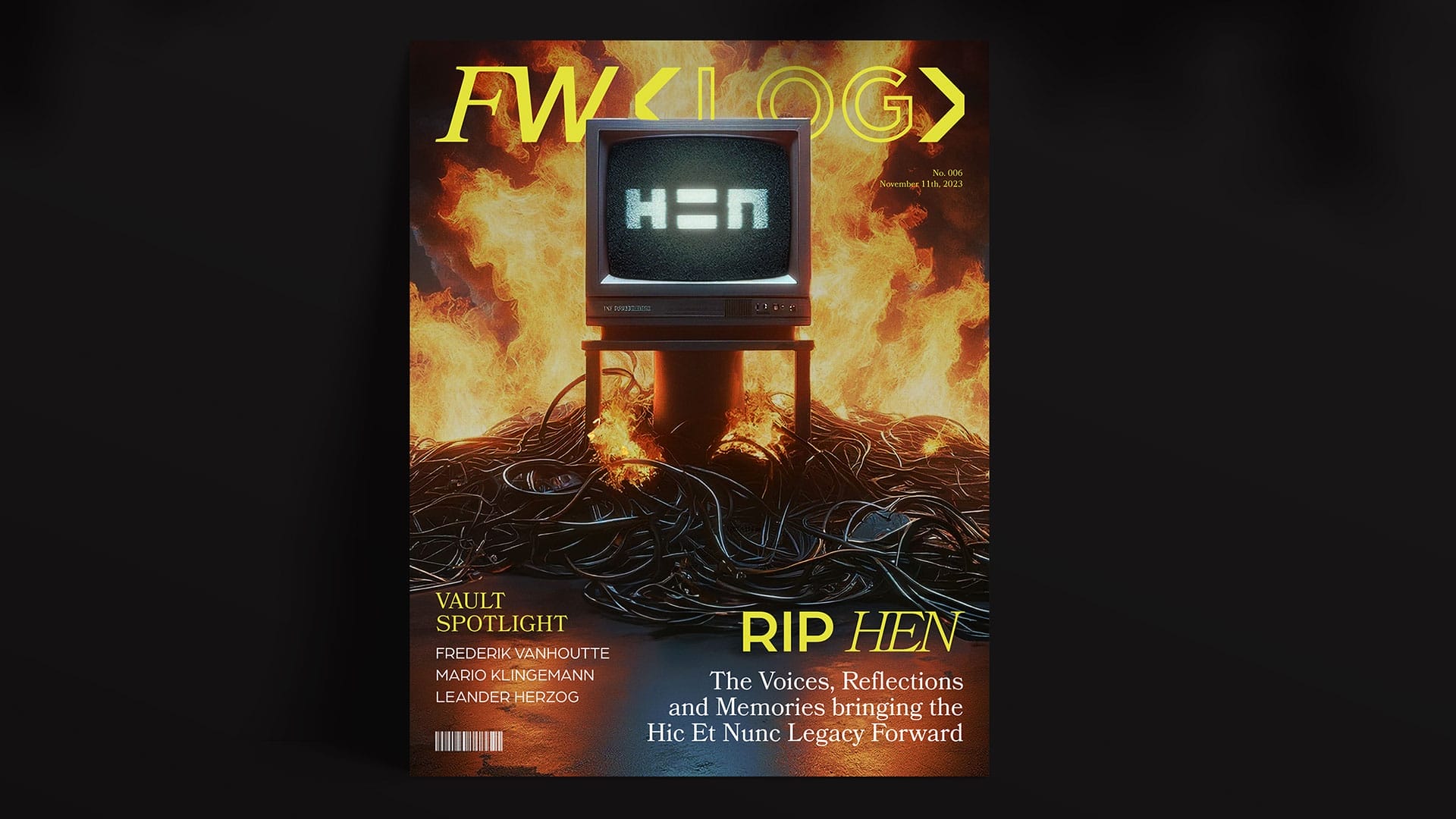

FW LOG: Editorial Feed No. 006

Introducing FW Editorial Feed No. 006, where we revisit the genesis, journey and legacy of Hic et Nu

Fakewhale in dialogue with: Nestor Siré

We are pleased to present an in-depth interview with Nestor Siré, a Cuban multimedia artist whose w

ART MARKET May 2024: Highlights & Staff Picks

As May draws to a close, Fakewhale Gallery’s ongoing, on-chain ART MARKET exhibition on objkt.