Fakewhale in Dialogue with Michael Lowe

In our conversation with Michael Lowe, a collector whose passion for 1960s and ’70s conceptual and minimalist art has shaped one of the most distinctive archives of its kind, we explored the intersections between memory, material, and meaning.

From his first encounter with Duchamp’s Boîte-en-valise to his reflections on collaboration, analog collecting, and the evolving art landscape, Lowe invites us into a world where ideas take precedence over form and where collecting becomes an act of preservation, curiosity, and care.

How did your interest in 1960s and ’70s conceptual and minimalist art first take shape? Was there a particular piece that marked the beginning of your collection?

In 1987, I purchased a multiple project by William Copley titled SMS (Shit Must Stop), published in 1968. Copley invited artists from all prevailing “isms” to participate in having multiples produced and marketed to avoid dealer interference in profits and artistic judgments. Artists as diverse as Duchamp, Lichtenstein, Yoko Ono, Lee Lozano, Ray Johnson, and Walter De Maria participated—73 artists in all.

This was my introduction to artists’ books from the 1960s and 1970s and the beginning of my collection. Through research, primarily reading Artforum from the ’60s and ’70s, I developed an interest in Minimal and Conceptual art. I made contact with artists, curators, dealers, and collectors, and began buying books as well as artworks.

At this time, I had been an antique dealer since 1970. As an autodidact, I obviously viewed this new period with a lack of knowledge but a burning desire to know. I had a distanced view of a period in art history that had been superseded by Neo-Expressionism.

What criteria do you use when selecting works and artists that embody a radical conceptual mindset? And how would you describe what makes your collection distinct compared to others in the same field?

In selecting works, I have tried to select works which were, in their time, considered radical, based upon contemporary source material. By collecting primary documentation such as exhibition catalogues, magazines, books, and other documents, I began to view the works in their contemporary context.

During the 1960s and 1970s, the art world was not the art market. There were fewer collectors, fewer dealers, possibly two art fairs, and much less money.

I purchased European works for the most part, as prices were then much more reasonable for all art in Europe. Stanley Brouwn, Hans Peter Feldmann, André Cadere, Daniel Buren, Niele Toroni, Olivier Mosset, and Franz Erhard Walther represent radical positions taken and followed throughout their careers.

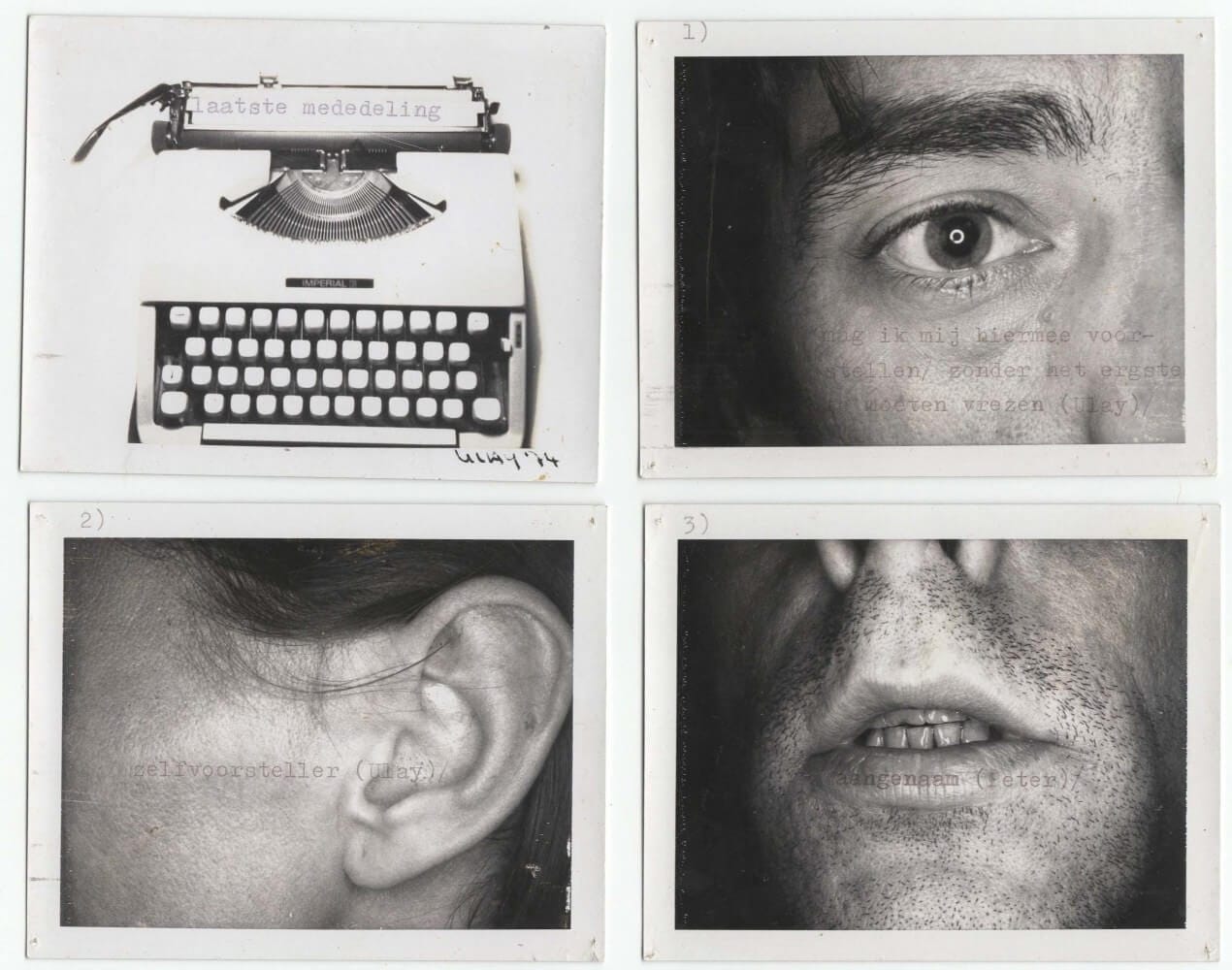

My collection possibly differs from most in this field in that I have collected in ancillary areas of the artists’ productions as well as their unique works: mail art, artists’ records, exhibition announcements, performance photographs, primary documentation, and films. The new art demanded experimentation in new mediums.

Among the works in the ML Collection, is there one piece that you feel particularly represents your curatorial vision, or that carries a personal story you’re willing to share? We’re curious.

I have a Boîte-en-valise by Marcel Duchamp, which I purchased from an artist called Ed Plunkett. I visited Ed to purchase mail art by Ray Johnson and exhibition ephemera.

In the course of visiting Ed for the first time in Manhattan, I entered his shotgun apartment, which was filled to the brim with stacked paper along the narrow hallway walls, hoarder-style. The difference being that the piles contained gems of documentation and mailed artworks. Ed mentioned that, in the distant past, he collected artworks and that the apartment was considerably more of a social space and studio, unlike its present condition.

He had purchased artworks with the help of an inherited stipend in the 1950s and 1960s. One of the works was a B version of the Duchamp Boîte-en-valise that he purchased from an exhibition at Sidney Janis in 1953 for $125.

Ed expressed interest in the Duchamp work and was asked if he would be interested in buying the work. As the $125 was beyond his means, Mr. Janis told him that he should own the work and was willing to take payments when possible, and to take the work with him.

Ed decided to sell the Boîte to me under the same conditions, $25,000, take the work and make payments.

As a cornerstone of my collection, I am forever grateful to Ed for his generosity in the late 1980s to pass on not only the work but the spirit of an earlier time.

The 2012 exhibition “Using Photography” brought to light works that use photography as a conceptual tool. What were some of the main challenges you faced in preserving and presenting such fragile materials as vintage prints or mail art postcards?

My photography collection is comprised of conceptual photography and performance photography from the 1960s and 1970s, as well as historical precedents such as 19th- and early 20th-century “performance” photographs, spirit photography, and, at times, scientific photography.

The 2012 exhibition Using Photography was a great opportunity to exhibit works which are normally kept in files, archival boxes, and drawers. I am fortunate to have a space with light conditions, not in direct sunlight, that allow for safe exhibition of photo materials. I try to be conscious of preservation; however, I admit that I am not a museum but strive to be a good custodian.

You’ve frequently collaborated with curator George Kurz, including on projects like Blank Generation and FotoFocus 2024. How did that collaboration come about, and what has it allowed you to explore that you may not have pursued on your own?

FotoFocus 2024 was an iteration of the FotoFocus Biennial in Cincinnati and the Midwest region. George Kurz is a close friend of mine and a serious collector of art. Blank Generation was an exhibition of George’s collection of 1970s–1980s Downtown New York culture, the art, music, and fashion scene. The exhibition was in my gallery space, but the collection was George’s.

We do, however, crossover in our interests and did a joint exhibition in 2014, which combined works from the 1960s to the 2000s for FotoFocus.

In an age of digital collecting and online platforms, how do you see the role, and the value, of “analog” collecting, especially when it comes to physical works and archival materials like correspondence art or minimalist sculpture?

I believe that analog collecting is the most satisfying version of collecting. Without the physical presence of artwork, we are left with the possible obliteration of our entire artistic heritage during a power outage. As an organizing tool, online platforms certainly are valuable. As vehicles of commerce, online platforms are valuable but dangerous, in the sense that forgery is rampant and money wasted on inexpensive fake art is still money wasted.

Care must be taken to verify descriptions of materials, methods, and condition without a physical viewing. Provenance can be falsified online through repeated auction listings bearing false information. AI does not listen to reason.

All of this doomsaying is to say that, even so, I have found amazing works online and forged strong bonds with sellers, which would not have been as easy without technology.

Looking ahead, are there any upcoming acquisitions or collaborations you’re particularly excited about? And how do you see the field of collecting conceptual art from the ’60s and ’70s evolving over the next decade?

I am looking forward to adding works to my collection. There are more opportunities at present to find photography, documents, and artworks online. Auctions are always surprising offerings from collections formed some time ago. Death, divorce, and disinterest are, sadly, generators of opportunity. I have purchased works by Yves Klein, Walter De Maria, Robert Barry, and Marcel Duchamp.

As to how my area of interest might evolve, I believe that there is interest to a certain degree, evidenced by the number of documents and publications from the ’60s and ’70s which are reprinted and purchased by young people. Curators are mixing ephemera and documents as context in exhibitions, which is a good sign. And… prices for works from this period are relatively low, especially when compared to contemporary works, even freshly minted graduate students still ask large sums for work. The art market is a victim of its own greed in many ways, and this is having an effect on prices.

On the other hand, non-“visual” art does not appeal to everyone, nor does non-visual art which is overly described, defined, categorized, and canonized. Personally, I am as interested in a stone or a scientific diagram as art. Banality is beauty much of the time.

fakewhale

Founded in 2021, Fakewhale advocates the digital art market's evolution. Viewing NFT technology as a container for art, and leveraging the expansive scope of digital culture, Fakewhale strives to shape a new ecosystem in which art and technology become the starting point, rather than the final destination.

You may also like

Erris Huigens, Anti-Monuments at FORM, Wageningen / Amsterdam

Anti-Monuments by Erris Huigens, at FORM, Wageningen / Amsterdam, 5–30 January 2026. “They are n

Softimag, On the Threshold of the Visible and the Simulated

Perspective by Softimage (Katja Breder, Viola Del Monte, Hannes Hochmuth, Lara Jordan, Luka Keresman

Thomas Hirschhorn, LAST CHANCE: A Visual Manifesto on Learning from Art

“History never repeats itself, but it does often rhyme.” – Mark Twain And yet, we neve