The Counterpower of Piracy: Malta, the Mediterranean, and the Politics of the Sea by Sofia Baldi Pighi

The sea surrounding the Maltese archipelago has long been both a route of danger and a corridor of opportunity. Piracy endured for almost three hundred years, enriching Malta while igniting countless diplomatic tensions. At its peak, Maltese corsairing employed around 4,000 people and operated a fleet of some 30 galleys, playing a central role in ransoming Christian captives held in Ottoman territories. It also provided a base from which a highly organized fleet could engage in lucrative trade, attacking enemy ships and raiding ports for profitable plunder. Corsairs paid a fixed quota to the island’s government and were active in the slave trade, as well as in securing valuable goods, grain, and food supplies. As Professor Liam Gauci from the Maritime Museum – Heritage Malta notes, “We should look at corsairing as a motor of the Maltese economy at the time – just like Freeport and digital gaming are now.”

(Gauci, Liam. Get Rich or Die Trying, interview by Teodor Reljic. Malta Today, 20 April 2016.)

Today, Malta’s economy continues to operate along similar maritime logics — a hub for data flows, blockchain enterprises, and financial speculation. From Freeport logistics to crypto exchanges, the island still negotiates its prosperity through the management of circulation, risk, and controlled opacity: the same dynamics that once animated its corsair fleets.

Within the Malta Biennale 2024, a curatorial section was dedicated precisely to this theme, unfolding from the archipelago’s own site-specific history of corsairing and maritime trade — and from the broader ways in which pirates have long inhabited our collective imagination, from childhood tales to cinematic mythologies. The section, titled The Counterpower of Piracy, brought together Daniel Jablonski (France/Brazil); Dijana Protić (Croatia); Dolphin Club (Germany/France); Franziska von Stenglin (Germany); Goldschmied & Chiari, Matteo Vettorello, Post Disaster, and the Suez Canal Republic (Italy); Mel Chin (United States); Tom Van Malderen (Belgium); and the collective Artists Against the Bomb (Mexico), led by Pedro Reyes with participants from across the world.

Each artist presented a work inspired by the manifold meanings of piracy, which — within the context of the Malta Biennale 2024 — served as a lens through which to reconsider the very idea of the Mediterranean: a space where trade, exchange, peace, and violence have always intertwined. Who were these pirates? Many had departed from Mediterranean ports, fleeing crimes or seeking fortune, often working alongside the Maltese. In alliance with the crusaders, these seafaring adventurers came to “run” the sea — targeting so-called “Turkish” vessels and any ship that presented an opportunity for plunder. Some captains, such as Guglielmo Lorenzi or Alfonso de Contreras, became legendary figures, while others met their fate through prosecution and hanging. By the time the Hospitaller Knights of St. John arrived in 1530, the Mediterranean had already been shaped as a constellation of smaller seas — with islands like Malta serving as vital bridges along transversal routes, perilous yet essential to the region’s historical fabric.

Today, piracy continues to inspire libertarian thinkers, who see in it a form of counterpower that escapes the control of governments and multinational corporations. The organisation of life on board has been interpreted by many historians as self-managed, a prototype of an egalitarian society. Scholars such as anthropologist David Graeber have reconstructed these “pirate utopias” — temporary autonomous zones of freedom, like Libertalia, the legendary pirate city said to have emerged on the coast of Madagascar.

It is within this framework that the curatorial section The Counterpower of Piracy — conceived by Sofia Baldi Pighi, Emma Mattei, and Elisa Carollo, together with scientific advisor Franco La Cecla (IULM University, Department of Humanities Studies, Faculty of Arts and Tourism) — takes shape. The section reconsiders piracy as a political and imaginative device: a lens through which to read the Mediterranean and its histories of resistance, exchange, and survival. Thinkers such as Heller-Roazen have described the pirate as “the enemy of all” — a figure that, in contemporary terms, may be embodied by Julian Assange, by activists involved in migrant rescue missions, or by community networks and self-managed health and childcare centres. In the digital realm, hackers and network saboteurs who reclaim the infrastructure of the web for collective and autonomous purposes also identify themselves as pirates.

What if we were to consider artists themselves as pirates — as uncomfortable agents who provoke debate, rather than as mere content for grant applications or the marketing strategies of cultural institutions? When the Knights fell and Napoleon reached Malta in 1798, piracy seemed to vanish from these waters. Yet perhaps the time has come to raise another flag — carried not by conquest but by imagination, a flag of shared resistance and renewed beginnings.

Daniel Jablonski (France/Brazil, b. 1985) presents a new site-specific rendering of Hy-Brazil — a phantom island that appeared on nearly every European chart from 1325 until 1870, when it was finally dismissed as a cartographic error. Imagined as a marvellous yet unreachable land, it occupied a privileged position in the imagination of the Age of Discovery, bridging travel literature, Christian doctrine, and Celtic folklore. Even today, references to the island of Brazil continue to circulate online, especially within YouTube ufology channels and conspiracy forums.

Conceived as a “cartography of errors,” the installation Hy-Brazil tells two intertwined stories: one about not finding what was sought, and the other about not recognising what was found. As explorers ventured further across the oceans, geographers gained opportunities to “correct” earlier maps. Yet, since the island of Brazil had to exist somewhere, it was gradually displaced — from the coast of Ireland to the shores of Newfoundland.

Advances in cartography — from the use of scale to the introduction of precise coordinates — allowed explorers to claim ever more “accurate” discoveries. Still, the predetermined objectives of their voyages shaped their perception of truth: Columbus, for instance, never realised (or never admitted) that the land he set foot on — not once but four times — was not Asia, but an entirely new continent.

Mel Chin (USA, b. 1951) presented an AK-47 assault rifle welded together, in which the arrangement of the weapons forms a cross. The flared configuration of the butt stocks explicitly evokes the symbolism of the Maltese Order of Christian Knights, historically engaged in violent conflict with the Muslim empires during the Crusades. The rifle — and its many variants — was first developed in 1947 in the former USSR. Cheap and easy to mass-produce, the AK-47 has become one of the most widely circulated firearms in history — “the second most sold object in the world after the rosary,” as noted by anthropologist Franco La Cecla, scientific advisor to this curatorial section.

Cross for the Unforgiven is a collision of symbols and worldviews: it intertwines the histories of brutal military violence and penitential sacrifice, overlaying them with the sacred promise of redemption in a field where no absolution is possible. Fundamentalist faith and the potential for violence are welded together within the shared body of the sculpture — a body that, if triggered, could only implode upon itself.

Post Disaster (Peppe Frisino, Gabriele Leo, Grazia Mappa, Gabriella Mastrangelo — Italy, est. 2018) presents a temporary occupation of the monumental space of Fort St. Elmo in Valletta. The barricade functions as a scenographic device that provokes a critical confrontation with the site and its layered symbolic charge. Although one of the most iconic landmarks of Maltese heritage, Fort St. Elmo bears the weight of the colonial processes that have shaped the territories and peoples of the Mediterranean through centuries of occupation and conflict. Through a series of spatial interventions, public conversations, and performances — developed in collaboration with the local artistic scene, including Sam Vassallo, Rivoluzione delle Seppie, Karmaġenn, Parasite, Alien Montesin, Accla, Epicure, and Tarzna — the collective stages The Unfinished Barricade: an action intended to disrupt the normative functioning of the war museum and to contribute to the formation of an alternative imaginary, collectively and unpredictably constructed. The project seeks to re-signify collective memory by critically engaging with the architectural, political, and affective nature of the site.

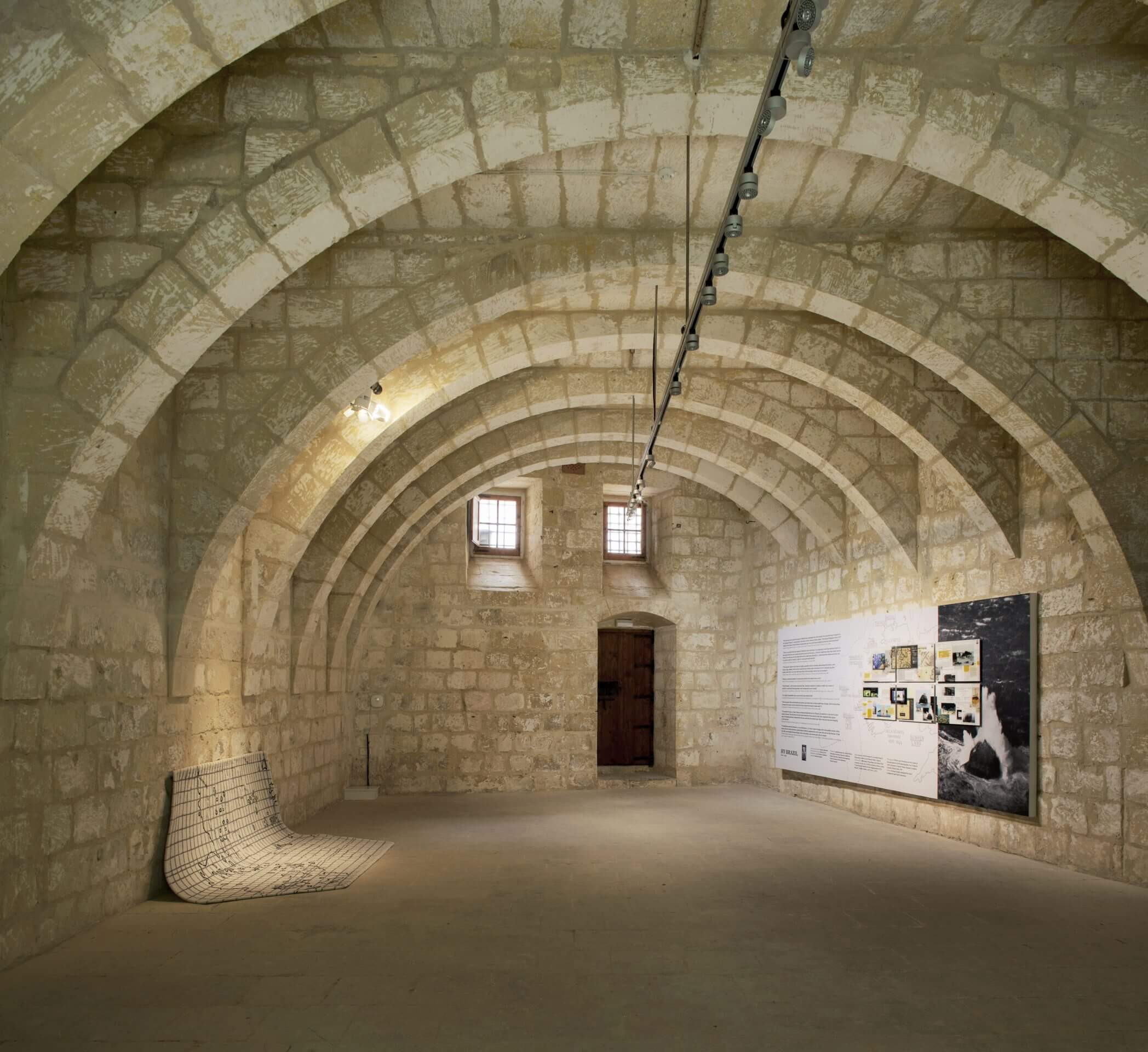

Thanks to Heritage Malta, the Maritime Museum, and the Cultural Directorate of the Ministry for Gozo, the curatorial section The Counterpower of Piracy of the Malta Biennale was hosted within some of the most emblematic Maltese heritage sites — including the ancient Citadel of Gozo, the Gozo Cultural Centre, the Grain Silos, and Fort St. Elmo in Valletta. The encounter between contemporary artists and historical heritage was made possible through the visionary direction of Heritage Malta — the national agency responsible for the preservation and promotion of the islands’ cultural patrimony. In a joint effort between this leading public institution and governmental support from the Ministry for Culture, Education, Foreign Affairs, and, notably, the Ministry for Tourism, Malta is currently investing in a large-scale strategy to reposition the archipelago as a cultural destination. This vision reflects a broader understanding of culture as a form of diplomacy and soft power.

Insulaphilia sought to explore how cultural heritage shapes identity, both historically and in the present. If today words such as identity, nation, and authenticity have become unsettling or even frightening, perhaps places themselves remain keepers of a knowledge we must learn to unearth. Cultural heritage must be examined in its conflictual nature — between the planned construction of memory and the political contingencies that have marked the Euro-Mediterranean landscape, tracing and re-tracing borders, territories, and militarised geographies.

In the case of Maltese heritage, we have learned to read hybridity as a defining feature of local culture. As James Clifford writes in Pure Products Go Crazy, identities often emerge strengthened by their apparent dispersion — only the impure products survive the grinding forces of capitalism and globalisation. At 450 Valencia Street in San Francisco, novelist Dave Eggers has opened a store selling bandages, hooks, headgear, and scarves for aspiring pirates — outlaws who defy established rules and “go to sea,” the ultimate symbol of freedom. From this perspective, the story of Malta is also one of changing flags: corsairs who, depending on the political climate or the loot acquired in a raid, would shift allegiance — the only flag that truly mattered was that of the Grand Master, the sole emblem able to elude the judgment of the Vatican court.

Today, the island still bears countless traces of its maritime history — stories of capture and liberation, trade and slavery, heroic and less glorious ventures. Tales abound of Muslim captives falling in love with their masters’ daughters, of secret escapes through caves, miraculous rescues of ships and sailors, and chapels built in gratitude for having escaped Turkish raids. Insulaphilia has examined the history of piracy and its local repercussions through collaborations with Maltese and international artists, engaging directly with local heritage sites to return to Malta its centrality — freeing its history from subordination, humiliation, and external instrumentalisation, and proposing instead a distinct identity on the global stage.

Keeping this framework in mind offers a vivid understanding of the sites where the Biennale unfolded — palaces and fortresses touched by the layered histories of piracy. The first edition of the Malta Biennale emerged within this dynamic landscape, entrusting artists with the responsibility of imagination in spaces that were never neutral, to tell of seas that connect rather than divide in the face of history’s fractures.

Now that the Mediterranean once again becomes a stage for exercising international law, and the right to solidarity, it must be reclaimed not only as a space of conflict and migratory tragedy, but as a terrain of resistance and collective agency — as seen in initiatives such as the Freedom Flotilla for Gaza. To hoist a pirate flag today is to refuse submission to unjust laws, to reclaim disobedience as a civic right, and to resurface the forgotten stories that still lie beneath the waves of the central sea.

Sofia Baldi Pighi

Sofia Baldi Pighi is an Italian curator and PhD candidate based between Milan and Gozo, Malta. Since 2017, her practice explores the intersection of art, historical heritage, and militant politics through exhibitions, public programs, and workshops. She is the Artistic Director and Head Curator of the Malta Biennale 2024, Insulaphilia, promoted by Heritage Malta and UNESCO. Baldi Pighi was part of the curatorial team for Italy’s first National Pavilion at the 14th Gwangju Biennale in South Korea (2023). She collaborates with institutions across Europe and Asia, including UNESCO-WHIPIC, Triennale Milano, Larnaca Biennale, and MOKA Museum. Baldi Pighi also works with international galleries and companies supporting art projects. She is a member of Art Workers Italia and IKT - International Association of Curators of Contemporary Art and contributes to publications such as NERO, Exibart, Modern Times and Fakewhale LOG.

You may also like

KEN OKIISHI · JOHANNES PORSCH · TANJA WIDMANN: Derivatives Affaires at Schleuse, Vienna

KEN OKIISHI · JOHANNES PORSCH · TANJA WIDMANN: Derivatives Affaires at Schleuse, Vienna 05/09/2025

Underneath the Paving Stone at Lunds konsthall, Lund

Underneath the Paving Stone by Lygia Clark, Anders Hergum, Valérie Jouve, Yuko Mohri, Kasra Seyed A

Fakewhale in dialogue with Tim Plamper

For some time, we have been following Tim Plamper’s work, fascinated by his ability to blend diffe