Fakewhale in dialogue with James Bloom

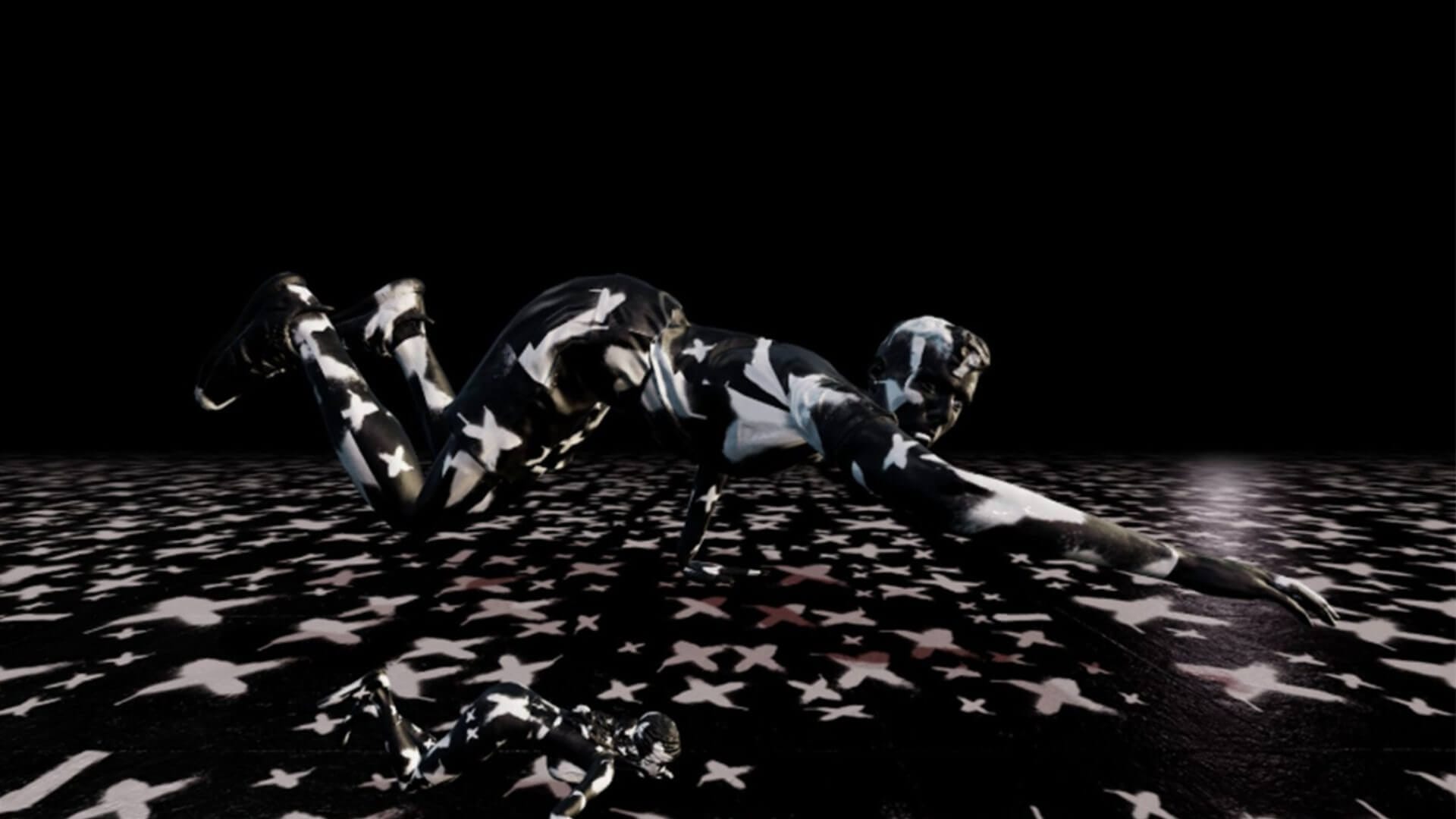

In his latest project, Half Cheetah, James Bloom tackles a theme that is as technical as it is existential: what happens when the algorithms that drive progress are broken down? Through the use of Reinforcement Learning systems and 3D scans of human bodies, Bloom makes a critical reflection on structures of progress and improvement in society and at the level of the body. At FakeWhale, we had the pleasure of asking him a few questions to explore the technical, philosophical, and aesthetic implications of Half Cheetah and his wider artistic research.

Fakewhale: Your work begins with a reflection on performance and the process of optimization towards certain goals. How have Reinforcement Learning agents allowed you to question the notion of progress, so deeply rooted in our technological culture?

James Bloom: Reinforcement Learning models are self-improving. Like most AI models they try to optimize for a given task, so they really embody the systemic idea of improvement and progress that is a controlling theme in society. In Half Cheetah I turn these models against themselves and in doing so break this pattern of progress.

You use terms such as “helplessness,” “competence,” and “efficiency” to describe the evolutionary stages of AI in motor learning. You frame these phases as parallels to human physical development. How did you approach the risk of anthropomorphizing the algorithm, and to what extent was this intentional?

These Reinforcement Learning models are used to mimic the behaviour of mammals, so the similarities are hard to ignore. Equally, machine learning models are also being used to organise and direct our goals as a society. We’re definitely becoming more entangled with these kinds of algorithms, all the way down to our bodies. This is something Half Cheetah explores.

You chose to transpose the AI agent’s movements onto 3D scans of real human bodies. What aesthetic and ethical criteria guided the selection of these bodies and the act of de-identifying them?

These people, with different ethnicities and genders, have sold the rights to their body scans online, under fictional names. Their bodies have become autonomous digital objects, a kind of blank surface you can repurpose, either by ‘re-skinning’ their surface or by directing the bodies’ behaviour. In the digital environment, the body becomes contingent on the purpose of the buyer. This is the world we live in.

In Half Cheetah you use two Reinforcement Learning agents against each other. You describe the goals of the second model as “aesthetic” criteria. What are these criteria, and how did you encode them into the system? Would you call this a form of algorithmic curatorship?

In Half Cheetah there is an initial Reinforcement Learning model, which goes through the normal process of learning how to use its body and improve its proficiency, like we do. But the second model analyses the behaviour of the first model, breaks it down and re-orders it. This second model’s goals can vary but often when it reaches its end-goal it can look more like a failure than anything else. The model moves towards failure, it optimises for failure, so in a sense that is its aesthetic.

At one point in the project, you write that the raw material is not just objects or surfaces but “behaviors.” This semantic shift is powerful: what happens when behavior itself becomes an aesthetic object?

There’s a tradition in time-based media art of using behaviour towards an aesthetic goal. Bruce Nauman is a great example of this. Some of his work reveals the violence in behaviour and yet somehow manages to transcend it at the same time. My interest with Half Cheetah is how behaviours are systematized.

The final visual result is a hybrid dance, often unsettling, suspended between efficiency and failure, predation and clumsiness. How does this “aesthetics of instability” connect to your broader critique of technological narratives?

I’m aiming for a non-verbal experience. In order for me to get to that, there has to be a certain amount of instability. When you look at these pieces you can sense there is a pattern in the behaviour of the moving bodies. As people, we look for patterns and try to work out where things are going. But Half Cheetah doesn’t have a clear direction. By disrupting the direction of travel it shows how precarious things are.

The decision to present the work in real time, within an immersive environment, amplifies the sense of hyper-presence and control. What interests you in the relationship between public experience and the autonomous nature of the work?

I’m interested in people’s physical reaction to these pieces. The artworks are made up of body movement so elicit some kind of bodily response in the viewer. Having them in an immersive environment will make more of a physical impact on people.

The series will be accompanied by a book published by Mousse Publishing, conceived as a flipbook where the bodies move from page to page. How did you approach the challenge of translating a dynamic work into a sequential, paper-based medium?

I wanted to approach the book as an art object in itself and a flipbook seemed an appropriate format to display Half Cheetah. The team at Mousse are clever and have some great ideas about how to bring the movement of these models to life in printed form. We want to break the format slightly too.

From a technical perspective, you worked with tools and models also used in military and industrial contexts. What is your stance on employing these technologies in an artistic setting? Would you also see it as a political act?

I think there is a political dimension to the work, as this idea of progress and efficiency is a big feature of the power structures we live with. But I’m also aware that the goal-seeking impulse is something that’s inside all of us. The question is where does this take us?

Looking ahead, do you plan to continue exploring the deconstruction of skill and performance? Can you give us a preview of your upcoming projects or research directions?

I have a collaboration ongoing with the great Gottfried Jager, an underrated but important figure in generative photography. He really took apart the idea of photography as a representational medium and has had an understated influence on conceptual and abstract photography. I’m looking forward to showing this work soon.

fakewhale

Founded in 2021, Fakewhale advocates the digital art market's evolution. Viewing NFT technology as a container for art, and leveraging the expansive scope of digital culture, Fakewhale strives to shape a new ecosystem in which art and technology become the starting point, rather than the final destination.

You may also like

KEN OKIISHI · JOHANNES PORSCH · TANJA WIDMANN: Derivatives Affaires at Schleuse, Vienna

KEN OKIISHI · JOHANNES PORSCH · TANJA WIDMANN: Derivatives Affaires at Schleuse, Vienna 05/09/2025

FAKEWHALE in conversation with Jan Robert Leegte

On the occasion of the upcoming exclusive Fakewhale-curated release Walled Garden, launching June 5

Inside WUF Basel 2024: A Premier Press-Only Event for Contemporary Creative Culture

Every year, Basel becomes the focal point for the world’s leading journalists and art enthusia