Fakewhale in Dialogue with Chris Dorland

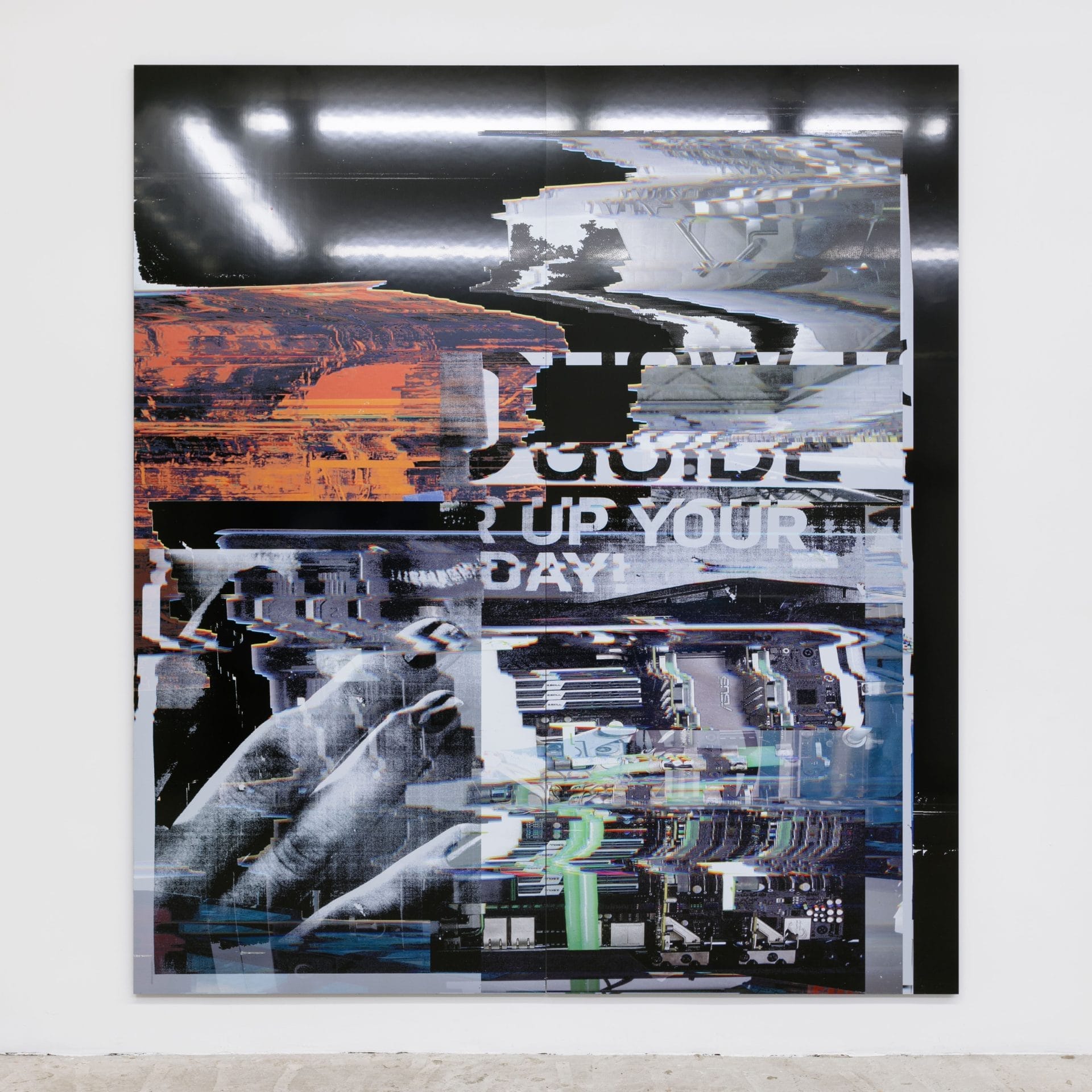

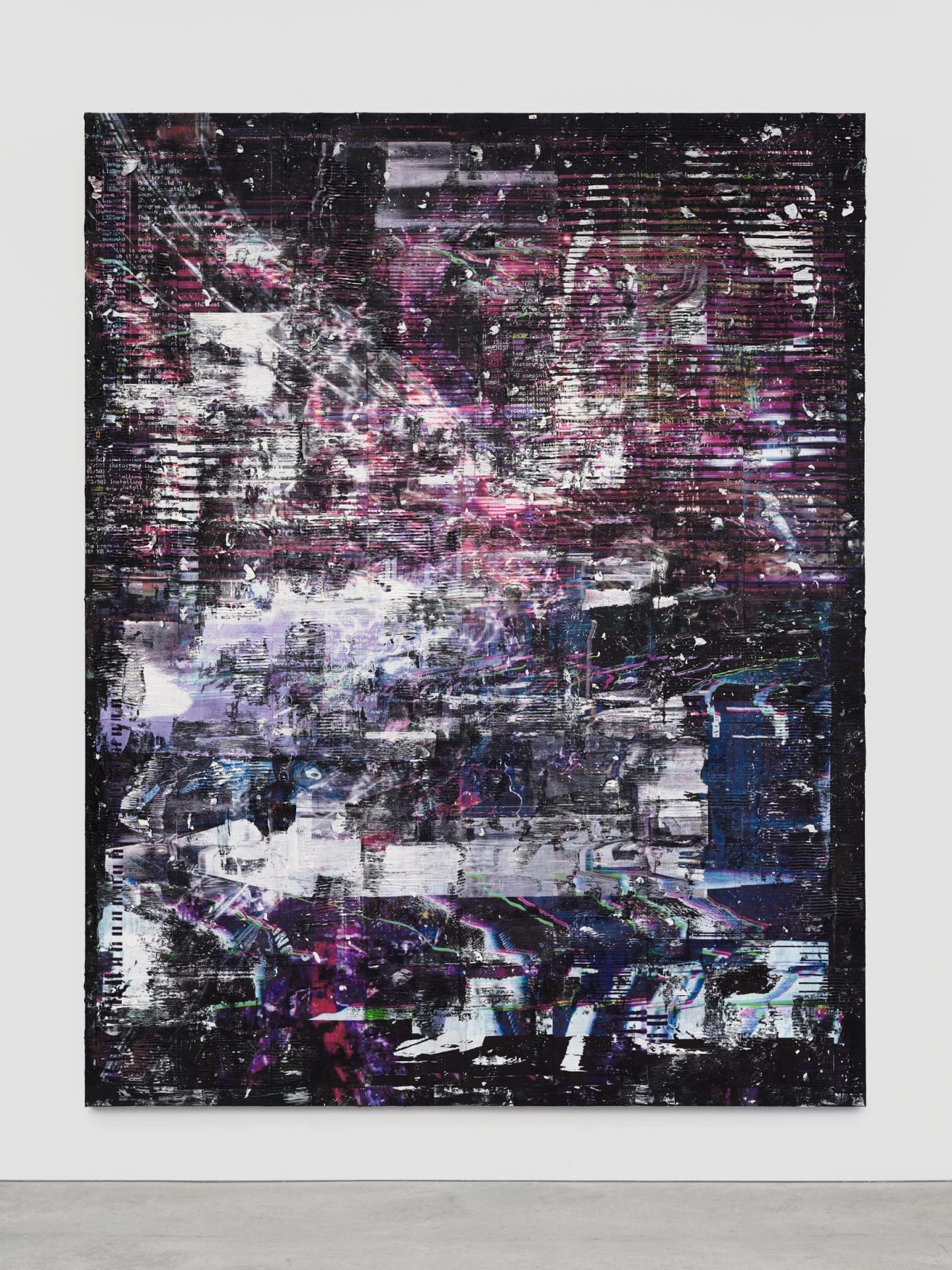

We’ve been following Chris Dorland’s work for some time now, captivated by his ability to fuse digital languages, analog remnants, and a near-prophetic take on the post-human condition. His paintings seem to erupt from a collision between material substance and the residue of corrupted systems, dense, layered surfaces where the glitch becomes expressive, and the aesthetics of digital ruin carry emotional and historical weight. At FakeWhale, we had the pleasure of speaking with Chris to explore the complexity of his practice and the visions that underpin it.

Fakewhale: Your work operates at the crossroads of painting, glitch aesthetics, digital ruin, and technological culture. But what’s striking is how these elements don’t merely depict dysfunction, they seem to transform it into emotionally charged, temporally complex imagery. How important is it for your work to carry emotional resonance, even when embedded in cold, digital aesthetics?

Chris Dorland: Emotional resonance is everything. It’s a critical point of contact between the work and the viewer. Even when the surface is synthetic, coded, or austere, the underlying goal is to move something in the body. We’re surrounded by systems that automate, flatten, and abstract, art remains one of the few places where a pulse can still be felt. My aim is to make work that engages the nervous system.

You’ve often spoken about your fascination with technological failure, the flicker of an old monitor, warped VHS tapes, compression glitches. How do you incorporate or simulate these moments of breakdown in your paintings? Is the glitch for you more of a conceptual stance or a formal strategy, or both?

Both. Glitch is a formal tool, but it’s also a way of thinking. I’m drawn to rupture, the crack in the system where something leaks out, something unintended or ungoverned. Glitches can be aesthetic, but they’re also political. They reveal fragility in structures that present as seamless. Right now, we’re watching legacy systems, technological, institutional, historical, glitch in real time. My work is in dialogue with that.

In your recent “Interface Paintings” and video works, there’s a distinct “surveillance-core” aesthetic, imagery that hovers between military drone footage and ambient digital dream. How does your practice reflect on algorithmic vision and the aest

hetics of control? Is there still space for the human eye to decode or reclaim these machine-distorted images?

“Surveillance-core” captures how ordinary it’s become to be watched, parsed, and predicted by machines. My work borrows from that visual language, grainy feeds, overprocessed signals, but reconfigures it through the slowness and tactility of painting. Painting demands physical presence. It asks the viewer to move, to linger, to look with intent. It reintroduces friction into a visual culture that’s constantly trying to eliminate it. That act of real looking, embodied, resistant, slow, is a form of reclamation.

You’ve described your childhood as a near-immersive experience in pop culture: VHS, video games, advertising, horror films. To what extent did that formative environment shape your visual language and your critical perspective on today’s hyper-mediated, hyper-capitalist visual systems?

My early childhood was a deep immersion in pop culture, sci-fi and horror films, video games, cable TV. My Dad loved exposing me to the spectacle, but always through his particular lens of radicalism. As academics, both my parents were steeped in countercultural thinking and postmodern theory. So while I absorbed mass media in all its intensity, there was a critique baked in from the start. That contradiction shaped me: I love the image, but I don’t trust it. That tension runs through the work, a kind of haunted fluency. And of course, things have only intensified since then. The spectacle has metastasized. We’re now living through what feels like a total psychic and spiritual collapse.

The title of your Nicoletti show, Clone Repo (server ruin), taps into a hybrid vocabulary of biotech and infrastructural collapse. How do you approach titling in your work? Do titles serve as narrative cues, conceptual anchors, or atmospheric suggestions for your viewers?

Titling is the final graft. Once a work is finished, photographed, complete, I start thinking about language. Sometimes titles come from narratives I’ve written and later dismantled; other times they arrive as fragments, atmospheric hints. A good title can ground a work or disorient it. Either way, it becomes part of the surface.

You’ve described your creative process as “punching in the dark”, a constant restructuring of matter and meaning. In an age of automation and streamlined processes, how essential is the raw, nonlinear time spent in the studio, the slow, physical confrontation with the work as it unfolds?

It’s everything. That wasted, circular, solitary time is the heart of it. There’s something sacred about being alone in a room, working by hand, making decisions no one else will see. In an era obsessed with efficiency, that kind of slowness feels radical. It’s also where the surprises happen, where form misbehaves and something unexpected emerges.

Your art explores glitches, viral systems, corrupted networks, but also the potential beauty in error, the possibility of redemption. Looking ahead, do you believe that art, and painting in particular, can still offer symbolic resistance or transformation within a hyper-capitalist, increasingly automated system?

I do. It’s complicated, painting has always existed within systems of power and capital, but I think that’s part of its charge. In a time when everything is automated, surveilled, and scaled, painting insists on the human hand and a different understanding of time. It’s slow. It’s physical. It’s small in scale but large in presence. That doesn’t make it pure, but it does make it potent. It reminds us that not everything has to be legible, trackable, or monetized. That reminder is resistance.

fakewhale

Founded in 2021, Fakewhale advocates the digital art market's evolution. Viewing NFT technology as a container for art, and leveraging the expansive scope of digital culture, Fakewhale strives to shape a new ecosystem in which art and technology become the starting point, rather than the final destination.

You may also like

Léo Fourdrinier in conversation with Fakewhale

Introducing Léo Fourdrinier Born in 1992, lives and works in Toulon. Visit Artist Website Fakewhale

In conversation with François Vogel

Introducing François Vogel Artist: François Vogel – Birthplace: Meudon, France, 1971 –

WUF Basel 2024: Solo Press Showcases Curated by Fakewhale

On June 11-12 WUF will be hosting an invite-only event for the press at Bar Rouge, Messepl. 10 Basel