When Nothing Weighs More Than Stone

There is something irredeemably inert in the object. We touch it, move it, measure it. Yet the very act of handling it marks its domestication. Sculpture, perhaps more than any other medium, bears the risk of consensus: it appears stable, complete, assertive. And for this reason, it has always been viewed with suspicion.

The twentieth century carried out a long and deliberate dismantling of sculpture, conceptually, symbolically, and linguistically. It wasn’t a rejection of matter per se, but a removal of its aura. When Duchamp, in 1917, flips a urinal and presents it as art, he is not merely redrawing the boundaries of artistic practice. He is introducing an asymmetry that forever contaminates the object. Sculpture is no longer what is shaped, but what is selected, pointed at, displaced. No longer creation, but choice.

In 1969, Joseph Kosuth wrote that “art is the definition of art.” The artwork ceases to be an extension of the body and becomes an extension of language. Within this framework, sculpture turns into an obstacle, a material interference in a conceptual field. The artistic gesture migrates to the realm of propositions, systems, enunciations. It is no coincidence that works like One and Three Chairs become paradigmatic: the chair as object, as word, as image. But in the end, nothing remains of sculpture except its semiotic potential.

Even architecture, the more institutional sibling of sculpture, undergoes a similar treatment. Gordon Matta-Clark slices through walls, hollows out buildings, exposes their wounds. His “building cuts” are anti-objects: not constructions, but deconstructions. What emerges is no longer the building, but its structured absence. A sculpture made of voids, as if emptiness itself could become volume.

More radical still is Robert Barry’s position when he states: “Nothing seems to me the most potent thing in the world.” Nothing, not as subject matter but as condition, becomes the true object of art. A show may consist of an empty room, an electromagnetic field, a series of dates or intentions. The artwork is not what is seen, but what is assumed, inferred, hypothesized.

But it is not just the artists who dismantle sculpture. Critical theory also plays a part in its decline. In her seminal Passages in Modern Sculpture, Rosalind Krauss shows how modern sculpture progressively abandons the pedestal, the center, the figure. It opens itself to time, to the body, to context. The work invades space, disperses, becomes an event. And when, in Sculpture in the Expanded Field, Krauss introduces her now-famous diagram encompassing “site construction,” “axiomatic structures,” and “land art,” it becomes clear that sculpture is now everywhere except where we once thought it was.

This is not merely a historical process. It is an ontological one. The plastic, three-dimensional, stationary form is what most resists semiotic fluidity. It is what most exposes the vulnerability of the artwork to fetishism, commodification, and ownership. To dismantle sculpture is to attempt a non-possessive aesthetics, a form of reception that resists appropriation.

And yet, something remains. Not the object, but its refusal. Not the sculpture, but the thought that dismantled it. The anti-form, the process, the subtraction, the gesture as artwork. A genealogy that runs from Yves Klein to Tino Sehgal, from Piero Manzoni to Hélio Oiticica, from Eva Hesse to Santiago Sierra.

Because, as Wittgenstein wrote, “the logical forms of reality never coincide with those of ordinary language.” In the same way, the forms of art no longer coincide with those of the visible. Sculpture, in this new grammar, is no longer an object. It is a question.

The Inverted Pedestal: A Genealogy of Anti-Sculpture

It is no longer form that imposes itself, but its negation. Sculpture, which for centuries embodied the highest expression of plastic autonomy, is progressively deconstructed until it disappears. The gesture of inverting the pedestal is not merely symbolic; it is an epistemic rupture, an act that challenges the entire logic of the object as visual fetish, as stable presence in space.

Already in the twentieth century, the historical avant-gardes acted against monumentality. Duchamp’s gesture, placing a found object within the semantic field of art, dissolves the necessity of carving. The Ready-made stands in direct opposition to the very idea of craftsmanship, of form shaped by the hand. Authorship shifts from execution to selection, and the gesture moves from material to language.

But it is with Minimalism that sculpture is brought to its threshold. Donald Judd denies sculpture as such, preferring the term “specific objects”: modular, industrial structures with no center, no narrative. The work represents nothing, alludes to nothing, aspires to nothing. It is a body in space that declares its own seriality and neutrality. The pedestal is abolished. The work sits on the floor, within the environment, on the same level as the viewer.

Yet even this neutrality is already a language. Robert Morris, in his text Notes on Sculpture (1966), insists that the meaning of a work does not come from form itself, but from its relationship to space, time, and the body. Sculpture is no longer an object but an event: a situated experience, a cognitive process.

This trajectory becomes radical with conceptual art. Artists not only reject form, but erase all trace of it. Lawrence Weiner writes sentences describing works never realized. Michael Asher removes walls. Robert Barry works with radio waves. Sculpture becomes what remains of its own erasure: an active absence, a theoretical imprint.

Meanwhile, Land Art and Arte Povera carry material outside the museum, immersing it in landscape, in time, in instability. Richard Long walks as sculptural gesture. Giuseppe Penone grows a tree. Art and life merge, and form becomes the natural consequence of an action, not of a plastic will.

In this genealogy of anti-sculpture, each step is an erosion. Marble is abandoned, then the pedestal, then the exhibition space, then the artwork itself. The object, once the cornerstone of aesthetic experience, becomes an obstacle. What remains is context, thought, time. Sculpture is no longer a presence, but a disruption. No longer mass, but threshold.

The pedestal has been overturned. And in its overturning, it has freed sculpture from the necessity of appearing.

Latent Matter: When Form Is Time

Not everything that appears truly is, and not everything that is needs to appear. This inversion has shaped many of the artistic practices that, since the postwar period, have reformulated the relationship between matter and duration, between sculpture and time. Form is no longer a stable attribute, but a delayed possibility, an event that may never occur and yet still leaves a trace.

Consider Roman Opalka, who in 1965 began painting numbers in progressive order from 1 toward infinity, as an unending record of time. Or On Kawara, who inscribed each day of his existence onto a canvas with its exact date. Here, form is nothing more than the material residue of time spent, a form that coincides with the very duration of living. Sculpture, in the traditional sense, is entirely dissolved, and yet everything becomes sculpture: each canvas, each date, each act of counting becomes a body that bears witness.

Time is no longer a frame, but matter. It is not a parameter of the work, but its primary substance. In certain practices, such as those of Tehching Hsieh, time becomes proof, endurance, a performance consumed through the repetition of a gesture or the self-discipline of life as artwork. In this sense, the body itself replaces stone. It is flesh that sculpts, yet never allows itself to be fixed.

Temporal sculpture is invisible sculpture. It cannot be touched, moved, or restored. It is composed of presence and disappearance, memory and anticipation. The artwork no longer exists where it can be preserved, but where the eye arrives too late, where thought reconstructs. It is what remains in the viewer’s consciousness, not what is arranged in space.

In this light, even documentation becomes the work. Photography, video, oral or written narration: everything that transmits a past event becomes latent matter. It is not a support, but a secondary surface that absorbs time and redistributes it through new forms of presence. It is in this transformation that sculpture finds its continuity in time, not as permanence, but as reactivation.

Form then becomes what extends through time by way of its own dispersals. A carved stone is matter fixed. But an action, a gesture, a concept transmitted through stories, images, or successive repetitions is a form that does not need to be fixed, because it has already entered history through other channels. The work exists because it continues to speak, not because it continues to exist in space.

Ultimately, what is shaped is no longer marble, but time itself. The artist is no longer a shaper of matter, but a director of durations. Each work is a temporal device operating through memory, projection, and expectation. Form is no longer what is seen, but what is remembered. And perhaps, even what is imagined.

The Weight of Absence: Strategies of Emptying and Subtraction

When Bruce Nauman installs an acoustically altered room in which the visitor becomes aware of their own body as a source of discomfort, he is not sculpting space, but absence. When Michael Asher removes a wall in a white cube, he is not creating an artwork, but erasing a threshold. In both cases, sculpture is not what is seen, but what is missing. Form becomes an echo, an interference, a subtraction that generates a new kind of attention.

A logic of emptying runs through much of conceptual art. Lawrence Weiner claimed that the work did not have to be realized, it only needed to be formulated. “A sculpture is what happens in space when you think about it,” we might say, paraphrasing him. In this way, the object becomes secondary, physical presence unnecessary, meaning anchored in language rather than in matter. A silent explosion in the temple of form.

Marcel Broodthaers also played with this absence: fictional museums, empty vitrines, catalogues without works. Everything pointed to what was not there, and yet everything was dense with meaning. Absence is never a neutral void. It is a charged space, filled with expectations, frustrations, and questions. The work becomes a device, a structure that activates the viewer, rather than an object that reassures them.

The weight of absence is measured by the density of thought it provokes. It is sculpture that does not occupy space, but inhabits the mind. The gesture of subtraction is, ultimately, an act of force. It removes in order to reveal. As in Taoist thought, where the void gives function to the full, absence here becomes what renders presence legible. It is not a rejection of matter, but a redefinition of its role.

Contemporary art has often chosen to walk this fine line, where form dissolves to let the idea emerge. Where the material is no longer marble or bronze, but time, space, and silence. It is sculpture made of air, yet capable of weighing more than a column.

The Symbolic as Matter: Words, Instructions, and Ideograms

The paradox introduced by artists like Sol LeWitt is that a sculpture can consist solely in its execution instruction: “A cube whose sides are equal in length and whose surfaces are white.” There is no need to see it. It is already complete in the mind. Language becomes invisible architecture, mental construction, a verbal form that shapes the space of attention.

Yoko Ono, in her Instruction Pieces, also abandons any claim to the object: “Draw a map to get lost.” Sculpture, in this case, is the semantic shift, the imaginative act, the projection of an action that may or may not be performed. The artwork does not reside in its execution, but in its potential. Not in the result, but in the proposal. The idea is sculpted within the symbolic.

This grammar has deep roots, grounded in what we might call constructive iconoclasm. Zen tablets, koans, and haiku already held the capacity to condense vast meanings into minimal forms. They were not images to be contemplated, but tools to displace perception. Likewise, Western conceptual art made text into a plastic medium: malleable, extensible, meaningful.

The symbolic, once relegated to the role of caption or commentary, becomes the protagonist of the work. The image is deferred, the material postponed, and what remains is semantic density, a play of ambiguities, a sculpture of meanings.

This transition is anything but neutral. Words are subject to cultural codes, elite languages, editorial conventions. This is why verbal sculpture is also a contested field. Whoever controls language, controls the work. Whoever possesses the grammar, sculpts reality.

In the act of writing an instruction or dictating a rule, the artist is no longer merely creating an artwork. They are creating a possible world. Art becomes plan, program, algorithm before its time. And it is within the symbolic that the most radical space opens up for a redefinition of sculpture, no longer as an object that occupies, but as a meaning that acts.

fakewhale

Founded in 2021, Fakewhale advocates the digital art market's evolution. Viewing NFT technology as a container for art, and leveraging the expansive scope of digital culture, Fakewhale strives to shape a new ecosystem in which art and technology become the starting point, rather than the final destination.

You may also like

A Narrow Strip Along a Steep Edge at Fort Lytton, Brisbane

A Narrow Strip Along a Steep Edge by Angel, Charlie Robert, Dean Ansell, Jessica Dorizac, Max Athans

7 Must-See 2024 Venice Biennale Pavilions

Set against the timeless splendor of Venice, the 2024 Biennale emerges as a dynamic showcase of cont

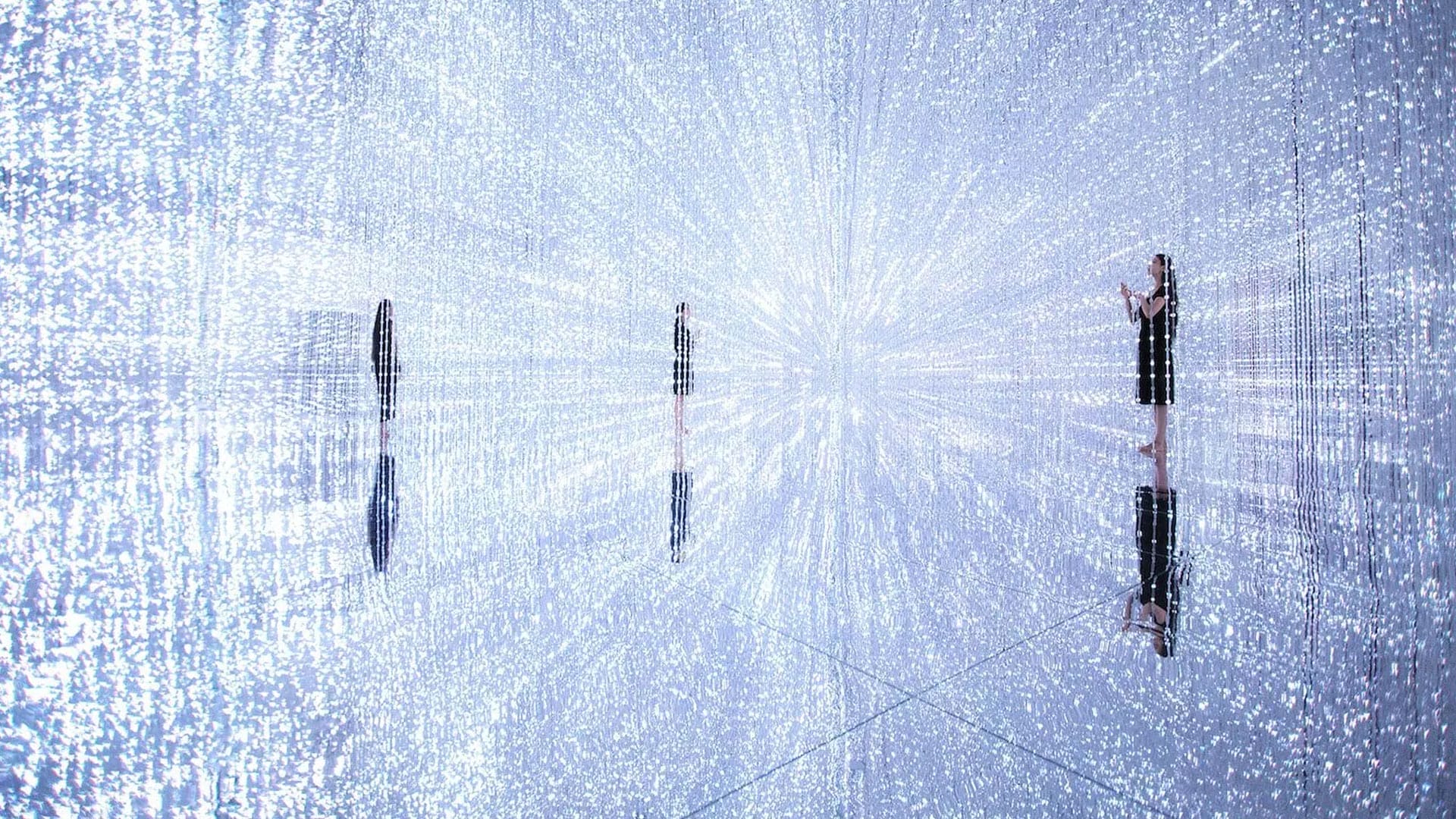

teamLab: Where Immersive Installations Become Nature’s Canvas

In a world where the digital and the organic are often seen in opposition, there exists a collective