Why I Destroy my Art: Fakewhale in Conversation with Francesco De Prezzo

– “Dear M, good paintings go to galleries, but bad paintings end up everywhere.”

With this provocation, Francesco De Prezzo opens the preface to his latest artist’s book, an entry point that encapsulates the complex paradoxes underpinning his practice. For years, we have followed his evolving body of work, drawn to his ability to deconstruct the image and reframe its ontology. His artistic language exists in a space of suspension, where the act of creation is inseparable from its own manipulation, and the artwork emerges as a site of negotiation, a dynamic interface between object and observer, image and absence.

In his work, documentation is never a neutral tool; rather, it emerges as a creative gesture that reshapes the conventional relationship between the artwork and its image.

We caught up with him for a relaxed Fakewhale conversation, eager to unpack the conceptual tensions and visual strategies at the heart of his research, and to learn more about his latest work, Liminal Figures.

Fakewhale: You’ve always had a borderline relationship with painting… can you tell us more about that?

Francesco De Prezzo: In 2015, I bought back every single work I had made before that year, often paying more than their original value. I promised all my friends and collectors that I was going to create something unique, something extraordinary. Then, I burned them all in a large bonfire.

That moment marked the true beginning of my relationship with painting.

On several occasions, you engage in the removal or dissolution of the artistic object…where does this obsession come from?

When a sculpture or a painting feels like it’s “on its way” or “just removed,” a strange kind of tension arises, one largely made of expectation. That’s precisely the substance my work is built on.

In 2023, for instance, I created a series of sculptures using simple photographic tripods, strategically placed throughout the gallery. They staged a kind of placeholder installation, as if the exhibition were either about to be replaced or still waiting for something else to arrive.

The suggestion was that something different, something other, was yet to come.

But in truth, the only certainty was that something was already happening.

Those metallic placeholders embodied the very possibility of display, they formed a sculptural presence in their own right. For me, they were already enough: as if they were actively engaged in “supporting” something elusive, intangible perhaps, yet oddly complete.

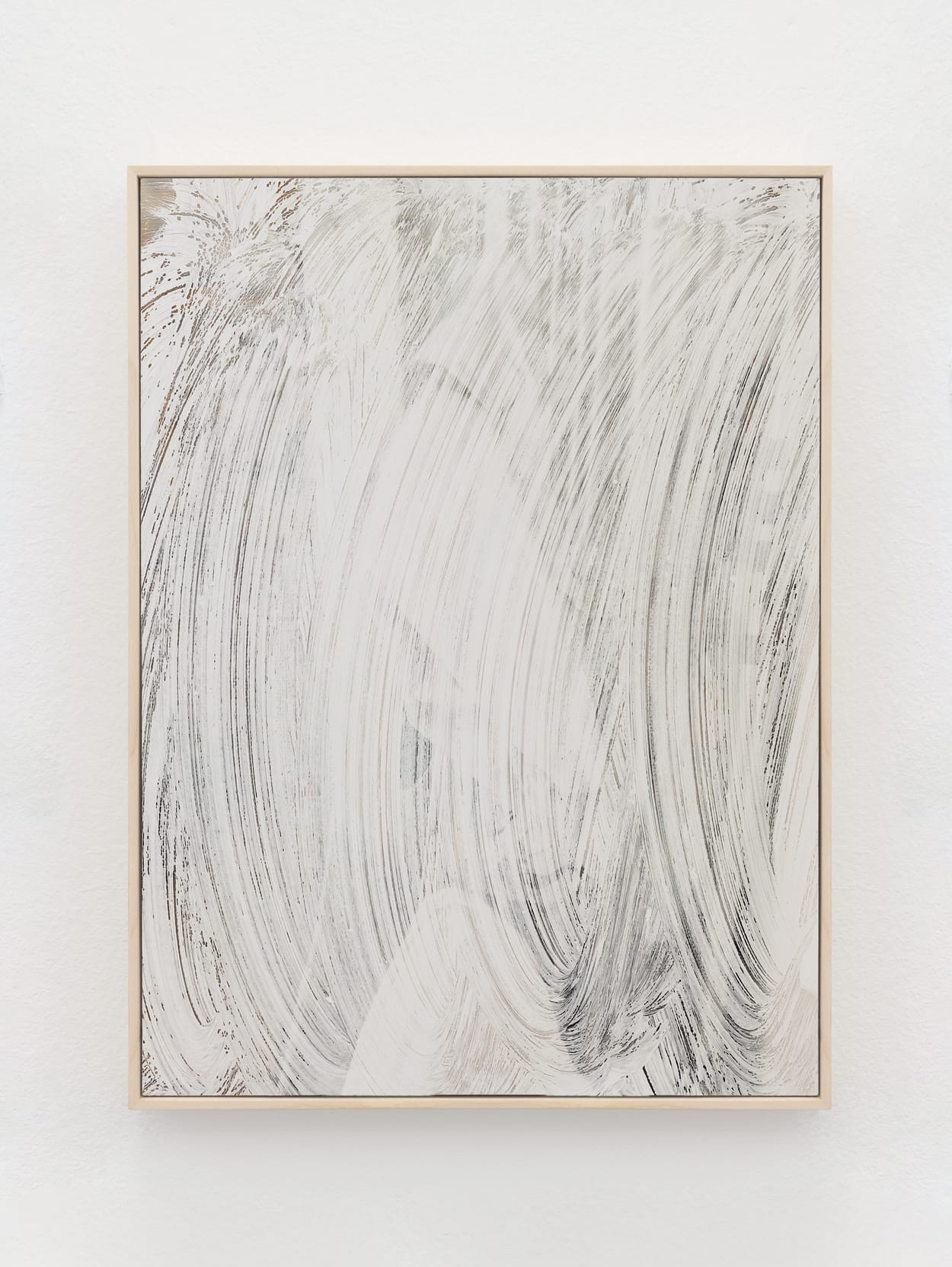

In your latest exhibition Liminal Figures, you chose to sharply separate the works from the physical space that hosts them. The seven paintings from the Null Paintings series appear almost alien to the exhibition context, as if they were disconnected from the space they’re meant to inhabit. What led you to make this choice? Was it driven by conceptual reflection or a formal necessity?

We usually think of an exhibition as a process of assembling, something that brings elements together, not pulls them apart.

But this time, instead of asking myself what to show, I asked what I wouldn’t show. That shift led me to radically separate the images of the paintings from the exhibition space itself.

In fact, I’m not even sure this qualifies as an exhibition.

In the documentation photos of Liminal Figures, the paintings appear almost as an afterthought. Looking at the sequence of images, you get the sense that the exhibition is either yet to be installed, or paradoxically, already dismantled.

I’m interested in playing with the audience’s expectations in this way, creating an unusual distance between the work and its context, yet still presenting them together.

The effect is similar to opening a folder of files: you’re faced with a collection of images that seem to belong to a preparatory or conceptual phase, but for me, this is the finished work

How important is the notion of “truth” in your practice, especially in relation to the documentation of exhibitions and artworks?

Every image is, first and foremost, a linguistic negotiation, it is already, inevitably, a construction.

Painting, sculpture, installation… does it really matter?

If everything ultimately ends up on blogs, social media, magazines, or even in art history books, inevitably reduced to the general form of an “image”, then it becomes clear that if visual matter is the medium, its visibility is the only thing that should truly concern us.

Referring to historical practices like those of Michael Asher, Ian Wilson, or the writings of Rosalind Krauss, you seem interested in a critique of exhibition conventions. What does it mean for you to “exhibit” today?

It fundamentally means letting go of the idea that an artwork is something to be “shown.”

You exhibit doubt, you exhibit disappearance, you exhibit the very impossibility of exhibition.

An exhibition begins when a low-res image starts circulating on WhatsApp, and maybe it ends when someone forgets it. But more often, it never ends. It’s a visual metastasis.

In this scenario, documentation no longer follows the event, it precedes and shapes it. Every work is conceived with an awareness of how it will be photographed, cropped, laid out. Every chosen angle is already a form of storytelling. In this sense, to exhibit is also to decide what not to show: what to obscure, what to displace, what to misalign.

The work is never fully given, it’s always partial, always in a state of assembly or ongoing negotiation.

For me, the question of “truth” fits precisely here: not as the authenticity of an experience, but as an awareness of the apparatus.

If the first encounter with the work happens through the flat space of an image, then the work must also know how to engage with that inevitable “pre-viewing”, and perhaps try to disarm it or redirect it elsewhere.

As Baudrillard wrote, the simulacrum has replaced the original. But perhaps today it’s no longer about distinguishing between original and representation, it’s about reading the threshold between what happens and what remains.

And in the end, if someone is still willing to look, then the show can go on.

The introduction to Liminal Figures seems to evoke a kind of hallucinated dimension, a sense of “constructing reality” from minimal suggestions, an imaginary that deeply resonates with your own poetics. How did you come to choose that particular text? And how do you see it intertwining with your work?

I had it on hand for a long time without really knowing what to do with it, then I realized it could be the starting point to build an entire exhibition around.

I didn’t know what to make of it. Maybe it knew what to make of me.

What struck me was its ability to turn the smallest details, a branch, the corner of a building, into full-blown apparitions.

That act of “seeing figures that aren’t really there” aligns perfectly with my interest in visual uncertainty: my works often invite the viewer to project something of themselves onto them, a mental shape, an expectation.

And that’s when it became clear:

you never only see what’s there.

You see what’s missing.

Recently, your work has also ventured into experimenting with artificial intelligence models…

Over the past year, I began working with a customized version of GPT-4, trained to generate complete layouts and configurations for potential exhibitions or installations.

The project quickly exceeded my expectations.

Through a casual, almost informal conversation, the model is capable of purchasing objects online for the exhibition, providing precise indications on where to place each element in the space, the distances between the objects, and the meanings associated with each piece in relation to the selected theme.

It feels almost like speaking with a curatorial assistant who is technically aware but devoid of actual consciousness.

For me, this process reflects a broader transformation: the art world is moving closer to a generative dimension, where not only exhibition texts, increasingly recognizable by certain stylistic tics, like the overuse of long dashes, but soon even the setups themselves, will be conceived by artificial intelligences.

We may be entering a phase where the artist no longer directly authors the work, but rather orchestrates technically automated dynamics already in motion.

Looking ahead, do you already have new directions in mind?

Yes. One of the directions I’m most committed to is working on pieces that will never be shown.

This is not a provocation, but a conscious decision to explore the value of artistic labor outside the logic of visibility and exhibition. I’m interested in the idea of a work that exists fully in its own process, art that refuses to perform itself for an audience.

I’m also thinking about forms of documentation that self-destruct after 24 hours.

As a reflection on the temporality of images and the accelerated cycles of digital circulation. What does it mean to preserve a work today? And what does it mean to let it vanish?

In a world saturated with content, perhaps nothing is already something.

fakewhale

Founded in 2021, Fakewhale advocates the digital art market's evolution. Viewing NFT technology as a container for art, and leveraging the expansive scope of digital culture, Fakewhale strives to shape a new ecosystem in which art and technology become the starting point, rather than the final destination.

You may also like

Myungchan Kim, Dahoon Nam, Ahyeon Ryu, Min Shin, Hán Yohan, Tactics for an Era, at K&L Museum, Seoul

Myungchan Kim, Dahoon Nam, Ahyeon Ryu, Min Shin, Hán Yohan, Tactics for an Era, at K&L Museum,

Manuel Esposito, Mattia Ragni, Are you tired? at Spaziolalepre, Tortoreto Lido

“Are you tired?” by Manuel Esposito and Mattia Ragni, curated by Spaziolalepre, at Spazi

François Bellabas, unloadingoverdrive at Contretype, Brussels

unloadingoverdrive by François Bellabas at Contretype, Bruxelles, 16.01.2025 – 23.03.2025. Ar