Losing the Backup Fragments of a Fading Digital Memory

A few months ago, my computer was stolen. With no backup. In an instant, I lost photos, writings, videos, and the archives of the last and first thirty years of my life. The external backup I had was faulty and irrecoverable. That was the end.

After a mild nervous breakdown, I followed the stages that psychologists recommend to cope with loss: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, acceptance. Yet, I’m not a “woman without memories” – I have the blurry, valuable memory of what I’ve lost. I accept the fallacy of technology, which ultimately reflects the fallacy of my own memory.

A story of an archive and its melancholy

In search of some form of impossible comfort, I recall a conversation with the artist Riccardo Benassi, where we discussed this very feeling, the nostalgia for a lost, perhaps idealized, technological past. Benassi coined the neologism “morestalgia” to describe a “hypermodern nostalgia,” felt in front of contemporary interfaces. It’s the result of a web that failed to fulfill our technological, idealized dreams, and now evokes a sense of absence. It’s a kind of “updated” loss, framed in our century, amidst hysterical web browsing, glitching digital empathy, and a flow of faint, vaporized memories.

Lately, I’ve been reflecting on the nature of digital archives, how artists’ works evolve from analog to digital, being preserved by museums, collectors, and curators. The true implications of such intense digitalization are both curious and potentially troubling: a well-ordered collection of digital files, naturally ephemeral, volatile…temporary. This gesture resembles the endless scrolling on social media, revisiting our Canon memory cards from the early 2000s, writing on a Y2K blog, collecting objects. Creating USB drives, external storage devices, and putting them in a drawer. Forgetting about them for years, thinking, “I’ll look at them someday.”

The debris of the internet, the debris of memory.

This concern, which has only truly struck me now, is the same one Jonas Mekas defined years ago as the “digital paranoia of losing things.” Multiple backups, clouds, mini drives, USB sticks, software. Archiving means having the courage to…lose? Perhaps to forget, if only temporarily? This, if you will, is the apotheosis of “the culture of convergence,” to quote Henry Jenkins. It was Mekas who famously said, “Memories are gone, but images are here, and images are real!” This is likely why he created the 365 Day Project in 2007, where he posted a video every day for an entire year on his online diary.

So, how can we have less digital paranoia?

An archive, like any true collection, arises from the obsession with having everything, being able to see everything, and creating a personal order for the things we want to keep present. The practice of archiving plays a crucial role in contemporary discussions in art, museology, cultural studies, and philosophy, all in the service of a subjective, intimate, and personal memory. Inventories use various media and uncommon techniques to break the dominance of the visual, operating on the psychological principle of personal attachment and idiosyncratic order, and professionally to guarantee wide, democratic, and shared public open access—an open form of knowledge and networking. Very interesting to think, as Hans Unrich did, that “an archive on its own can be a bit lonely”: he was the one to imagine an Interarchive to understand what happens when different archives create alliances, synergies between collections from all over the world.

Artists have always archived. Through their various formats, they document what they do, their practice, and their creations, and much of the residue, carefully sifted, of what ultimately remains of the artwork is what gets returned and shown in galleries: the journey, rather than the destination. We enter their thought processes, the creative flow that can’t really be materialized. In a sense, artists are the precursors to today’s explosion of the digital archive, a matter of containment, classification, and selective order. Clusters and accumulations of data, information, and memories that are both real and alive. I envision the museum as an archipelago of research and “emergences.” In this light, it wouldn’t house a synthesis but rather a network of interconnected relationships, creating potential future scenarios and cultural encounters. The archive is both a lab and an organism for us humans with short-term memory. It must be curated and activated: losing it? It’s a physical pain, much like death.

“But I know that memory is not a tool for exploring the past, but a medium. It is the medium of my experience, just as the earth is the medium in which ancient cities lie buried”.

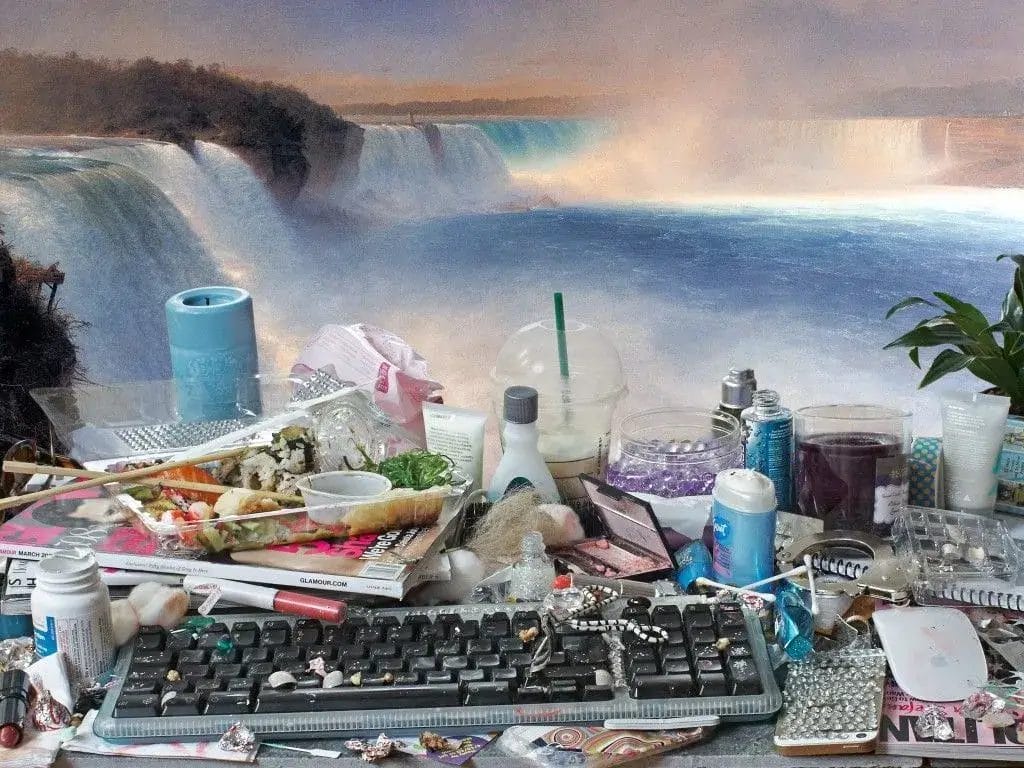

Artist Jon Rafman extracts his material from all corners of the internet, deeply considering immaterial memory. He often uses images, video clips, screenshots, and comments from platforms such as YouTube, Craigslist, and Reddit, without ever registering his sources. Both in form and content, his new media work reflects on our fascination with technological progress and digital advancements, as well as our simultaneous fears in confronting them. The medium Rafman uses allows him to analyze them in various ways, in both “real” and virtual spheres, whether on the artist’s website, in gallery spaces, or across social media platforms. Rafman’s “poor magic” echoes Hito Steyerl’s “Defense of the Poor Image”. By extracting video games, subcultures, and communities from the “Deep Web,” Rafman highlights human obsessions reflected in technology, as well as the loneliness and melancholy that have increasingly permeated our real lives. In Remember Carthage 2013, like in many of Rafman’s works, a sense of alienation and solitude structures the narrative: digital media make the story fully accessible through archival information, but also entirely distant from us. The atomized characters, sources, and remixes are anonymous, illusory. What does it mean for something to be real?

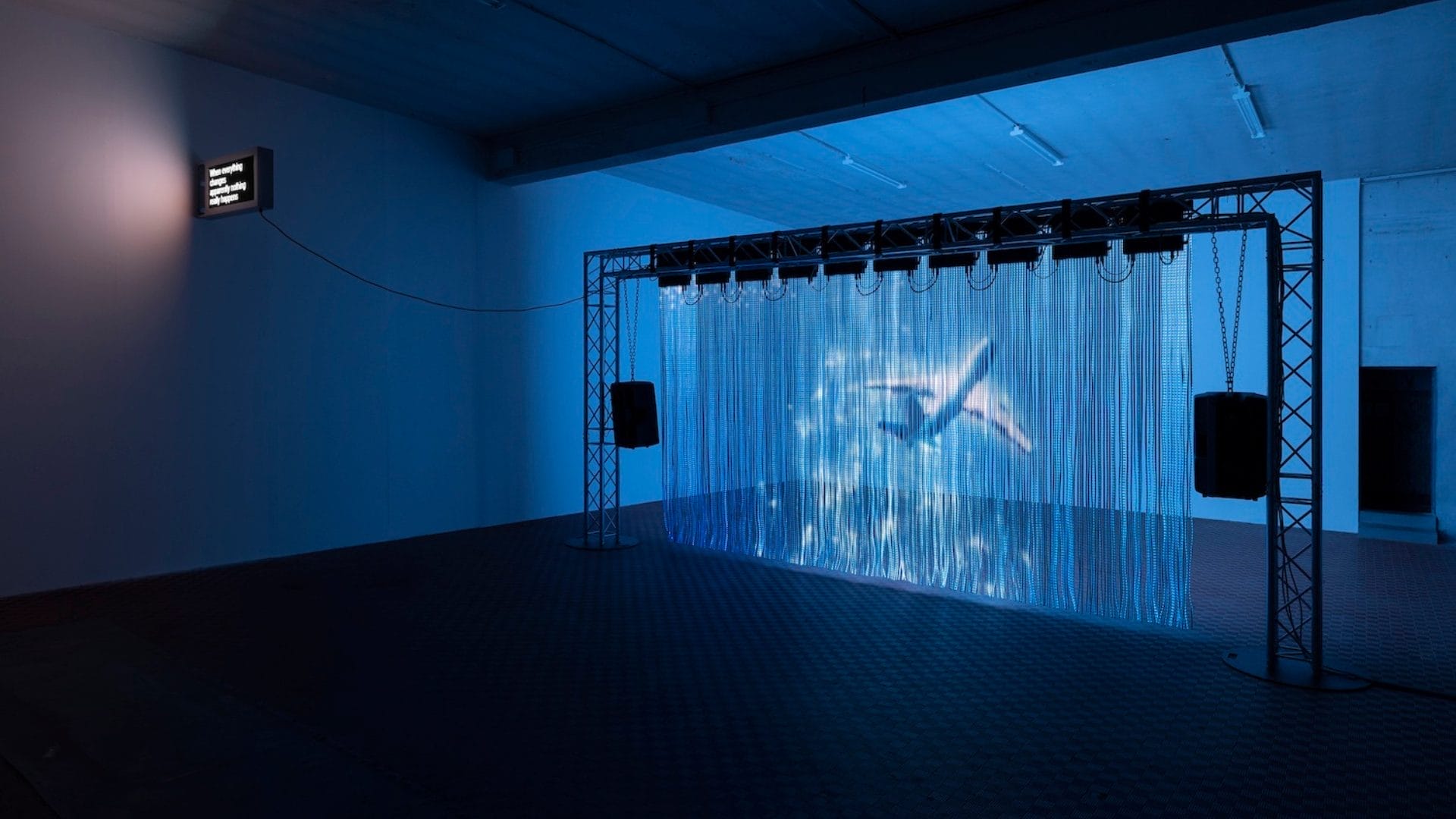

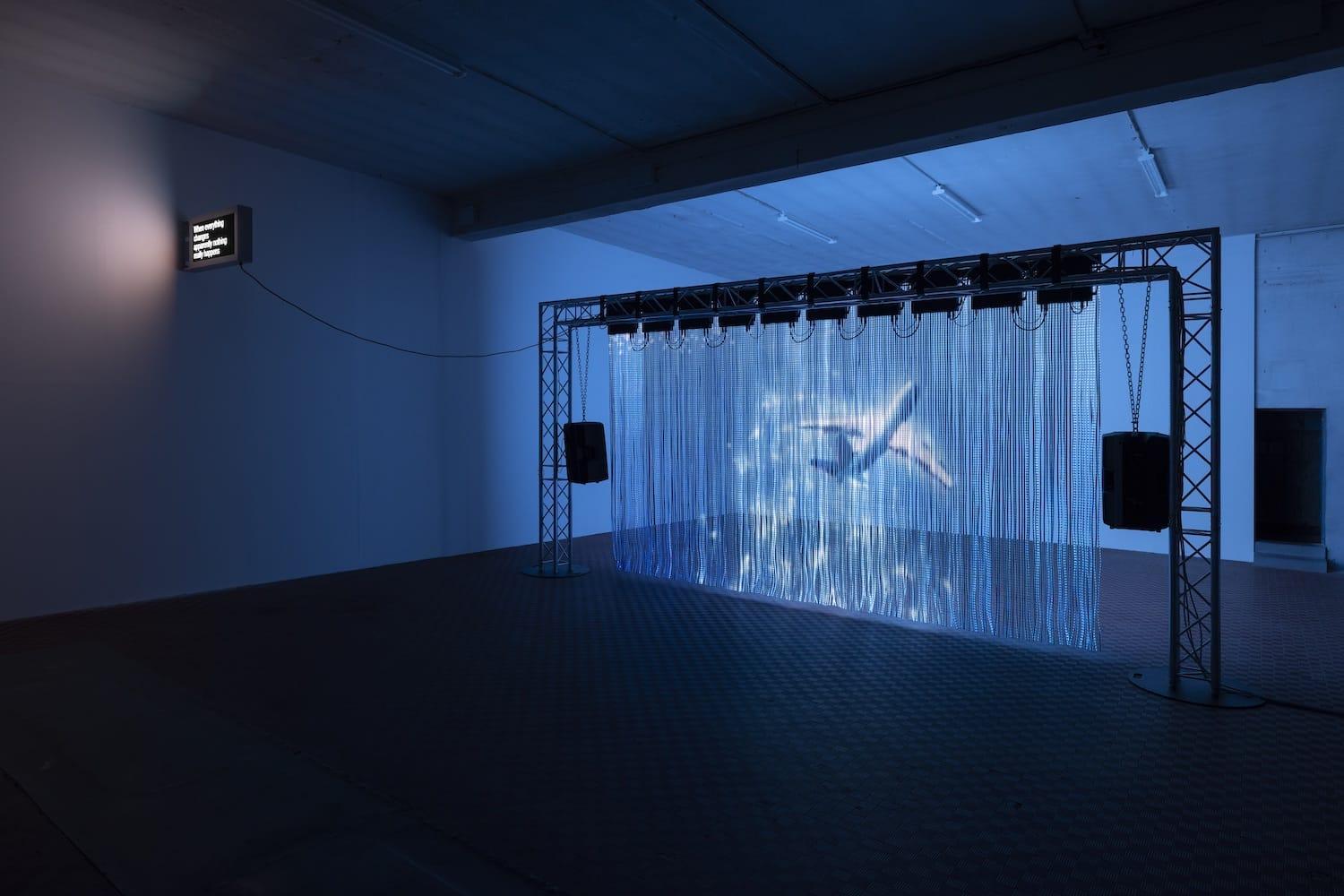

In a related yet distinct way, Eva & Franco Mattes, in Personal Photographs November 2007 (2023), installed at Frankfurter Kunstverein, created a site-specific installation involving cable pathways and a closed system circulating 101 personal photographs of the duo. These files are saved images, intentionally invisible, images with no viewers, yet omnipresent. It’s a reflection of the vast amounts of images that accumulate on our phones and computers, uploaded in verwhelming, unmanageable quantities.

Memory’s Transformation in the Age of Software

The ways in which individuals and societies access, shape, and remember the past are becoming increasingly influenced by digital technologies. “Mediated memories” refer to the technological mediation of our recollections, whether they are collective or personal. In her 2007 book Mediated Memories in the Digital Age, José van Dijck discusses how remembering is vital for our well-being, providing a sense of continuity between the past and the future, and between others and ourselves. According to van Dijck, “mediated memories” are “manifestations of a complex interaction between the brain and digital technologies, ‘embodied, enabled, and integrated.’” What van Dijck is questioning is how the changing materiality of our world has impacted how we remember, how the ability to reproduce, archive, and manipulate digital media changes the way we negotiate relationships and time. She identifies three major transformations, digitalization, multimedia, and “googlization”, that have shaped how we “store, retrieve, and adapt memories over the course of our lives”. This is a creative process, essential to memory retrieval, since the human brain is not designed to retain everything. The body makes mistakes that a machine wouldn’t: a machine doesn’t forget; it can copy, overlap, or move data instantly.

How does an artwork evolve over time, and what elements should or must be preserved? What does it mean to preserve works that inherently address and embody the idea of change in human memory? Some projects, such as the international symposium Transformation Digital Art, in Amsterdam, now in its ninth edition, examine the possibilities for conserving, archiving, and presenting digital art and media. This year, the symposium will explore the evolving space-time landscape of media art, encompassing all hybrid forms of video art, electronic art, software-based art, and internet art. Whether in museum galleries, art academies, virtual realities, or physical spaces, the symposium will address the ongoing evolution of digital art conservation.

The “slight forgetting”, the nervous “phobia”

We upload, we donate our most precious things to an electronic tool in files made of bits, uploading our private thoughts, emails, somewhere on our computers. In a way, we are all collectors: we engage in both analog and digital preservation, and we are terrified of losing it. Panic over system crashes, the dataphobia tied to the vulnerability of our digital identities, and the information we call “ours,” but is it really ours? This fear is tied to a broader anxiety about the disintegration of self-sufficiency and the illusion of control humanity has long sought to exert over its own reality, now mediated by technology. The potential loss of a “technological” memory thus becomes an existential void, an absence that threatens the integrity of our identity, in the fragile realms of the network, the web, a USB stick, or a hard drive. Are you perhaps that absence that Jacques Lacan taught me to call manque—that “slight oblivion” that underpins our human existence, a constant search to fulfill a desire, a “lost object,” symbolic? The fear of a breakdown, of the system failing, is the reflection of a fundamental tension between desire and the impossibility of its fulfillment, both in the psychological and technological spheres.

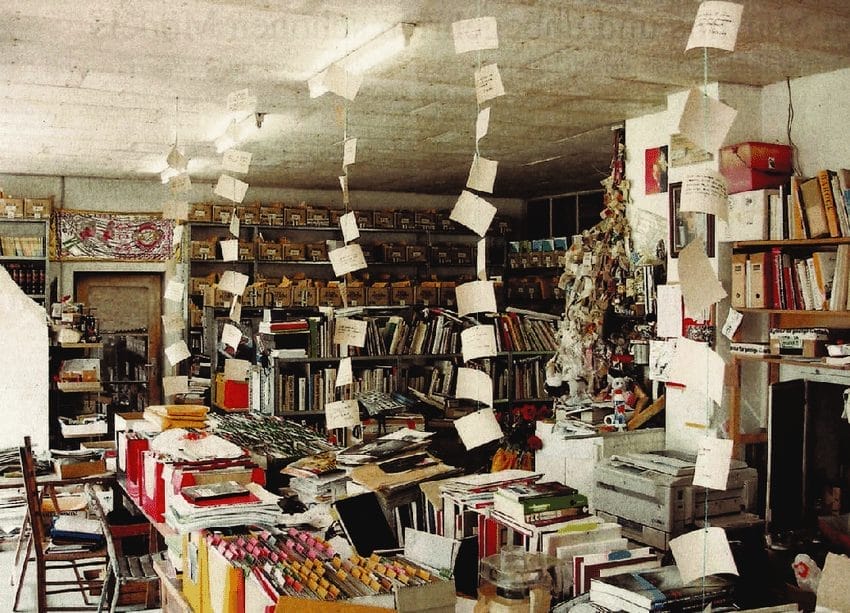

Harald Szeemann, in his own way, saw this coming. Although he had an email address, he never used it to write. His extensive archive began with the fax: when Szeemann traveled, he always carried two shopping bags full of paper, with printed emails that needed responses, written by hand. He would send stacks of documents by fax to his office, and then his office would send the response by email. In a curious way, Szeemann’s hard drive—the Harald Szeemann Archive, first housed in his studio in the village of Maggia—was this massive analog archive, 1500 meters of paper (the largest archive ever acquired by the Getty Research Institute), documenting his correspondence with prominent artists, curators, and scholars from the late 1950s until his death in 2005. Piles of paper, but more importantly, invaluable documents revealing the world and life of a passionate curator.

The things we take for granted can be lost, and much of the process of setting up an art exhibition may not be preserved. What remains of the exhibitions I’ve seen over the years? Did my collector friend make the right choice by keeping a journal, a tangible, analog diary? Did I make a mistake by only taking photos and not collecting press releases? And to think that, according to Vinton Cerf, one of the fathers of the internet, the web was “the surprise of being able to finally contain the enormous, infinite content of everyone.” He added, shortly after: “But always assume zero trust: never trust any network or online environment, no matter where you are. Assume nothing is secure.” A prelude to Vinton Cerf’s paranoia about the digital dark age. Some media will no longer be readable in the future; they will be obsolete. What if all the formats we use today, such as PDF, JPEG, TIFF, and WAV, become obsolete in ten or twenty years? What would happen to all this data we’re producing today? Would it all be lost?

The radical act of putting in the trash

The decision on what to digitize and what to archive is central to the entire process. This implies that we must be highly discerning: if an archive excludes nothing, it ceases to be an archive. When you place an archive online, it will inevitably have gaps, just like our memories are filled with holes. This represents one of the central paradoxes of our time: as we gain more knowledge about the natural and cultural world, and as more information becomes available to us, the world increasingly feels unknowable. And often overwhelming, even demoralizing. It seems as if we lack control. Thus, the act of archiving shifts from a means of communication to a way of being, to a work of art, to an existence. An archive doesn’t exist in any single, fixed form—it must always be remade, fluid, indefinable, much like our decisions and perhaps our perspectives. It has to live the struggle of “growing up” with us, as we do.

Overload, lack of control, trying to preserve, trying to contain. Then, suddenly, everything is discarded. The hyper-presence of digital spaces and the accumulation of information in databases is altering our relationship with memory. Emotional “indigestion”. I think about the film Happy Old Year (2019), directed by Nawapol Thamrongrattanarit, which examines the relationship between past and present, and how memories, often stored through objects and digital data, influence our identities and decisions. In Happy Old Year, Jean, the protagonist, struggling to organize her life and memories, faces the difficulty of letting go of the past, symbolized by objects and photographs. What does she do? She gathers all the objects from her past into numerous black trash bags, and…throws it all away. Physical memory, digital memory, the past we want to archive, and the future we hope to build: everything disturbs us constantly. In the film, Jean is confronted with her past in a world that doesn’t allow for losing oneself, avoiding responsibility, or achieving freedom. Jean takes the revolutionary step of consciously letting go of something, picking it up, and throwing it away.

The Archive as a Hyperlink Network

What is the issue with thought? Why is it essential for the human psyche to archive?

I view archives as vast hypertext databases: tools designed to store and organize intellectual and cultural activities, and to seek out new solutions and languages. The term “hypertext” refers to a non-linear, branching text, where “narratives have become multimedia and interactive“, as told by Ted Nelson in Literary Machines, 1992.

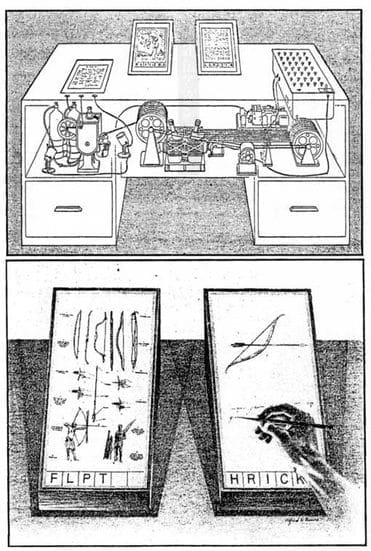

The archive, like hypertext and digital memory, serves to manage access and navigation of scientific information, storage, errors, and user access to academic and educational documents, where the risk of confusion and disorientation had already been identified as a symptomatic outcome. Content is categorized using a backtracking function (to return to earlier nodes), with navigation tools such as a graphical browser (fish-eye views, overview diagrams, etc.), query-based search functions (queries of databases to extract or update data based on specific search criteria), bookmarks, and more. Indeed, “The WorldWideWeb (W3) is a large-scale hypermedia information retrieval initiative designed to provide universal access to a vast universe of documents.” Hyperlinks contributed to the creation of cyberspace, where information is immediately and globally accessible, providing new, more exploratory and personalized ways of learning. The correlation between information, mimicking the functioning of the human brain, becomes information itself, interpretable with the help of an electronic interface. The fear of forgetting is deeply linked to the creation of the first web networks and storage tools, responding to the urgent needs of early technology pioneers: early examples include Vannevar Bush’s Memex, Doug Engelbart’s Augment, and Xanadu, as told in Computer Lib/Dream Machines (1973). These systems were concerned with representing “intertwingularity,” the connections that would help us navigate vast amounts of material and texts, and create new ones.

“Consider a future device… in which an individual stores all his books, records, and communications, and which is mechanized so that it may be consulted with exceeding speed and flexibility. It is an enlarged intimate supplement to his memory,” imagined Vannevar Bush.

This was the Memex, an imaginary machine conceived by Bush in 1945, a sort of mechanized library of files, detailed in his article As We May Think. It was intended to be an electro-optical machine, a large, translucent desk equipped with buttons that would activate mechanisms to search documents. This device was designed to allow users to move from one document to another in a way similar to how we navigate electronic hyperlinks, enabling better management of large quantities of information. The issue was always the same: how to manage an ever-growing mountain of research. The Memex is, in effect, an ancient form of mass memory: Bush described it as “a kind of mechanized private file and library,” a device where one stores books, records, and communications and can consult them with greater speed and flexibility. In other words, it was a “collective human memory amplifier.” Technology should not aim to replace humans but to enhance human (mnemonic) capabilities, this was the consensus among early computer scientists.

Ted Nelson, who coined the term “hypertext” in 1965, was a pioneer of the Xanadu system, which aimed to make all human information available in the form of hypertext. In 1995, Wired called Xanadu “the longest-running vaporwave story in computer industry history.” Nelson said, “in the copiousness of links and visual-verbal human material lies the problem of abstraction, perception, and thought.” Writing on paper is “a hopeless reduction,” the frustration of not being able to capture the vastness of our thoughts, knowing they will vanish eventually. “Everything is deeply intertwingled,” as Belinda Barnet concluded in Memory Machines: The Evolution of Hypertext (2013). In homage to cybernetic dreams of “man-computer symbiosis,” the mid-’80s saw the rise of the “personal computer” revolution, both in homes and workplaces. A technology for mediation and archiving: infinite memory!

Should we feel guilty for living in a society and software environment more focused on performance than on information? Societies without writing, encyclopedias, archives, memories, and backups are, ultimately, societies without history.

The Age of the Extreme Self

Why are we approaching data and metadata as negative? Maybe metadata is actually positive, and perhaps it leads to… I don’t know, a more focused existence? Perhaps mega-metadata will become our new loyalty points system. Why not? Infinite links and embeddings can be disguised as either fun or convenience.”

The Extreme Self Age of You

A dematerialized parallel already exists out there in the Cloud. What part of us are we backing up? Is it the archive itself that serves us, or merely the idea that it exists, for a time when perhaps, in the future, we might want to revisit it?

Does automation, which accelerates all processes of creation and sharing, always result in the optimization of human faculties, or does it risk becoming an overconsumption, too much to process? Being “exhausted” is now the mode of operation we must learn to live with in order to stay on track. Time and memory have become modern-day obsessions. This effect is also described by Hans Ulrich Obrist as “time shrink,” the feeling that life loses its essence when it is overwhelmed with experiences and stimuli, when subjected to an overly intense efficiency regime. What Rosi Braidotti termed “the importance of being exhausted” ends up reversing itself. A necessary overlap between the new and the archived, productive and unproductive time, that collapses life into an endless loop, an Infinite Jest in which users repeat the same actions endlessly. But if memory loses its sharpness, what should we focus on? If there are too many options, what do we choose? Is it truly so obvious, this exhaustion?

In the context of the database, the story fades away: the archive, bit by bit, one entry after another, forms bubbles with no final meaning, inexplicable, correlating our habits to parts of the world we didn’t even know we wanted to explore, to inhabit. And so, reality remains as the background of a desktop, made of narrative fragments. Just another line of code in the infinite archive.

The courage to forget

The dislocation and hyper-presence of media help to create spaces where tools, both pervasive and transparent, take the user’s time and attention, creating non-places where information is received and absorbed. In the “software society,” the device becomes woven into culture itself, linking it to the network through data, the accumulation in databases, and ongoing remediation. Concepts like cyborgs, hyperreality, and virtual ecology are my way of outlining the borders of the transformation, the deep remix, that has already happened and is continuing to unfold, and how the relational dynamics between author, reader, and content are evolving. Is the media experience a form of freedom? The process of linking a wide range of materials, observations, interpretations, and categories within enormous databases: is digital saturation a contradiction? Every “mediated” experience hides its own agenda within the intricate web of events (clicks) that happen in parallel. Dynamic events that don’t move, that are consumed passively, easy to digest but always in motion. The digital has, in this sense, become a spectacle of itself, performing omnipresently in the global everyday. We fear forgetting, losing memories, and want to store and archive everything, throwing nothing away.

Do we have the courage to forget?

Meanwhile, don’t spread this around, I’ve bought an external memory with billions of terabytes.

////

Bibliography

Riccardo Benassi, MORESTALGIA, Nero Editions, 2020

Hans Ulrich Obrist, Estrella de Diego, Future Archives: Conversation Series Volume II, Norman Foster Foundation Press, 2024

José van Dijck, Mediated Memories in the Digital Age, Stanford University Press, 2007

Ted Nelson, Literary Machines, Mindful Press, 1992

Ted Nelson, Computer Lib/Dream Machines, 1973

Vannevar Bush, As We May Think, The Atlantic Monthly, 1945

Belinda Barnet, Memory Machines: The Evolution of Hypertext, Anthem Pr, 2013

Shumon Basar, Douglas Coupland, Hans Ulrich Obrist, The Extreme Self: Welcome to Age of You, Walther Konig Editions, 2021

Matilde Crucitti

Matilde Crucitti (1996) is an author and curator based in Milan. She specialized in Visual Arts and writes for exibart, Coeval Magazine, and C41. She worked at the press office of Mimesis Edizioni and is a co-founder of the multidisciplinary collective Sinergie Naturali. Her current research focuses on the hybridization of electronic text, visibility, and new digital media, along with non-linear hyperfiction in contemporary software society, from both practical and psychological perspectives. Passionate about independent publications and electronic music, which she promotes through hybrid sound projects in the recording studio she co-curates in her city.

You may also like

4 – Carnage in Rockford Illinois

Washington D.C, United States On the Blackhawk helicopter ride to Washington D.C., Dasher spent the

Fakewhale Solo Series presents Out Ouch Pass by Scerbo

On March 13th 2024, Fakewhale is set to present “out ouch pass” — an exclusive Fakewhale Galle

Metaverse Bound: Traversing Alternate Realities through Art

Throughout history, “alternate realities” have woven their way into our artistic and nar