Fakewhale in Dialogue with Aaron Huey

Aaron Huey’s artistic practice cannot be pinned down to a single era, medium, or terrain, geographic or virtual. From high-risk field photography to AI-driven visual experiments, from collaborative campaigns with Amplifier.org to poetic reinterpretations of the climate crisis, Huey navigates through tools and contexts with an uncommon fluency. We at Fakewhale had the pleasure of diving into the layers of his work, exploring the fluid dialogue he creates between image, memory, and machine. What follows is a journey across deserts, data streams, and the blurred borders of photographic possibility.

Fakewhale: Which artists or movements have most influenced your creative vision, and how have they shaped your artistic journey?

Aaron Huey: My influences have evolved with every new tool and shift in my practice. When I started traveling to increasingly remote parts of the world in my youth, photography became my most portable tool for making art. I found myself in extraordinary situations: lost temples in Myanmar, protests in Iran, Taliban schools pre-9/11, and I realized documenting with a camera was the only way to bring back the depth, immediacy, and intensity I was seeing and feeling. I was all over the map geographically with my first cameras so my early influences were as well: James Nachtwey, Alex Webb, and many of my predecessors at National Geographic magazine. And at home, working in the American West meant engaging with masters like Bill Allard, Richard Avedon, and Joel Sternfeld, because you can’t escape their influence if you’ve photographed those landscapes.

With my more recent work in AI and virtual spaces, there was much less established visual language to draw from, which is why I fell in love with working with (and in) machines. Projects like Nano Sketches or Wallpaper for the End of the World emerged from a more blank canvas of influence. It’s both liberating and challenging to work without the crowded field of historical reference points that traditionally guides artistic practice. That said, I found inspiration in artists who were already pushing these boundaries. Trevor Paglen’s trajectory resonated with me – how his work evolved from documentary exposure toward abstraction and interrogating the very nature of images themselves. Others like Jon Rafman, Holly Herndon and Mat Dryhurst, Bas Uterwijk, and many of the artists in the darktaxa-project were pioneers in working with interfaces and algorithms, though I found myself studying the tools more than visual styles.

When did you begin to perceive photography not just as documentation but as a form of expressive art?

That line has always been fluid for me. Even in my earliest work in the Georgian Caucasus, I was searching for something beyond straight reportage, those in-between moments that carried more poetry than facts. I put every frame from that time (1998-2000 with my very first cameras and film) on-chain with my FirstFilm.xyz project, essentially minting my process itself. You can see my birth as a photographer as a 22 year old version of me learns how to use the medium. I think that approach deepened through my years of editorial work even if I was on assignments that were on the surface to “just document,” because it was never just documentation. As seen in recent work I did in the LA fires, that are far more than just reportage. I’ve always been looking for the in-between images.

I do think the definitive shift occurred when I started to hit the limitations of traditional publications and began collaborations with other artists, but especially when I started working with (and in) machines. The visual language immediately transformed, even though in my mind, it was a natural extension of the same conceptual threads.

In one of your quotes, you stated: “Photography has been a fluid and evolving practice since its invention in the 1820s, continuously reshaped by technological advancements and cultural shifts…”. How does this vision influence your approach to photography and the use of technology in your artistic work?

I’ve lived that evolution firsthand. From pre-cellphone black-and-white film days, to color slide film on a Leica M6 during my 154-day solo walk across America in 2002, to the first digital DSLRs which I used covering protests and war, and then the cellphone camera era. Now I work with synthetic photography, custom LoRAs, and virtual cameras. Each flowed naturally into the next and I never recoiled from the next possibility, each technological shift not just changing the tools we use but rewiring our perceptual framework. The rangefinder camera forced me to anticipate moments rather than chase them. Digital tools expanded my capacity for experimentation but also encouraged a different relationship with time and editing. And algorithmic photography has completely reconfigured my understanding of authorship.

Today, my conception of a “lens” extends far beyond glass and light. It can be algorithmic, virtual, or involve no physical camera at all. Each new tool is both liberation and constraint. I’m perpetually sketching new approaches, experimenting with new visual languages, resisting settlement into a predictable style. This constant state of reinvention keeps me engaged with the medium’s possibilities.

Your work often combines traditional techniques with advanced technologies. How do you integrate these two worlds in your projects?

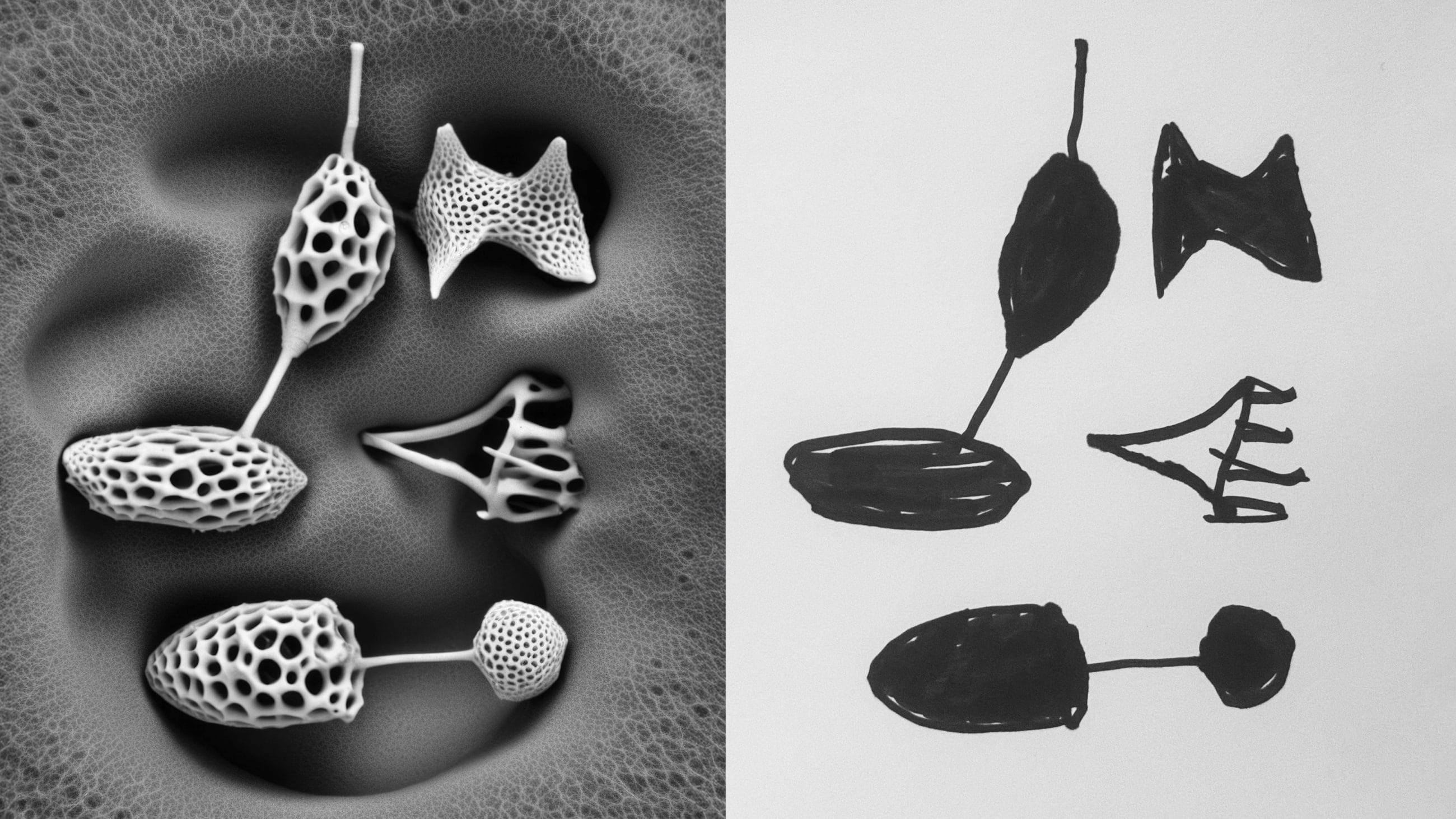

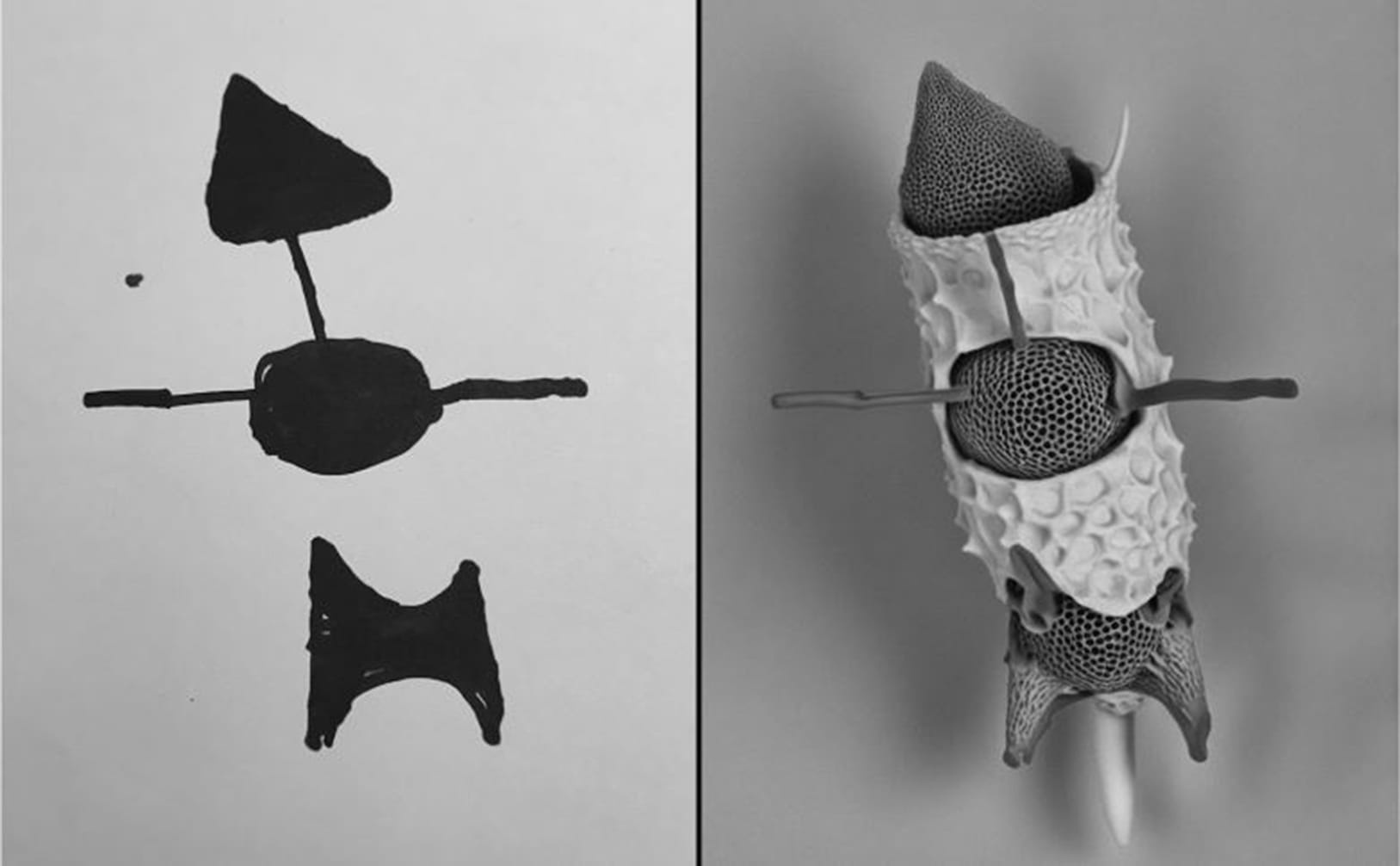

The integration just happens naturally for me because I’ve never really separated them into categories. Take the project I just did with my daughter Juno in Nano Sketches. I collected the fossils of nearly invisible ancient organisms called radiolarians that have been around for 550 million years, coated them with silver, and photographed them through a scanning electron microscope. Then I trained a LoRA on these images and ran my 8-year-old’s marker drawings through it, wrapping them in the photographic light and language of my archive, making whole new hybrid images. So where’s the line between what was done with hands and traditional techniques, what was done with a camera, and what was done with various advanced technologies like the SEM and AI? You can’t really separate it anymore because they are all wrapped up in each other in the final outputs.

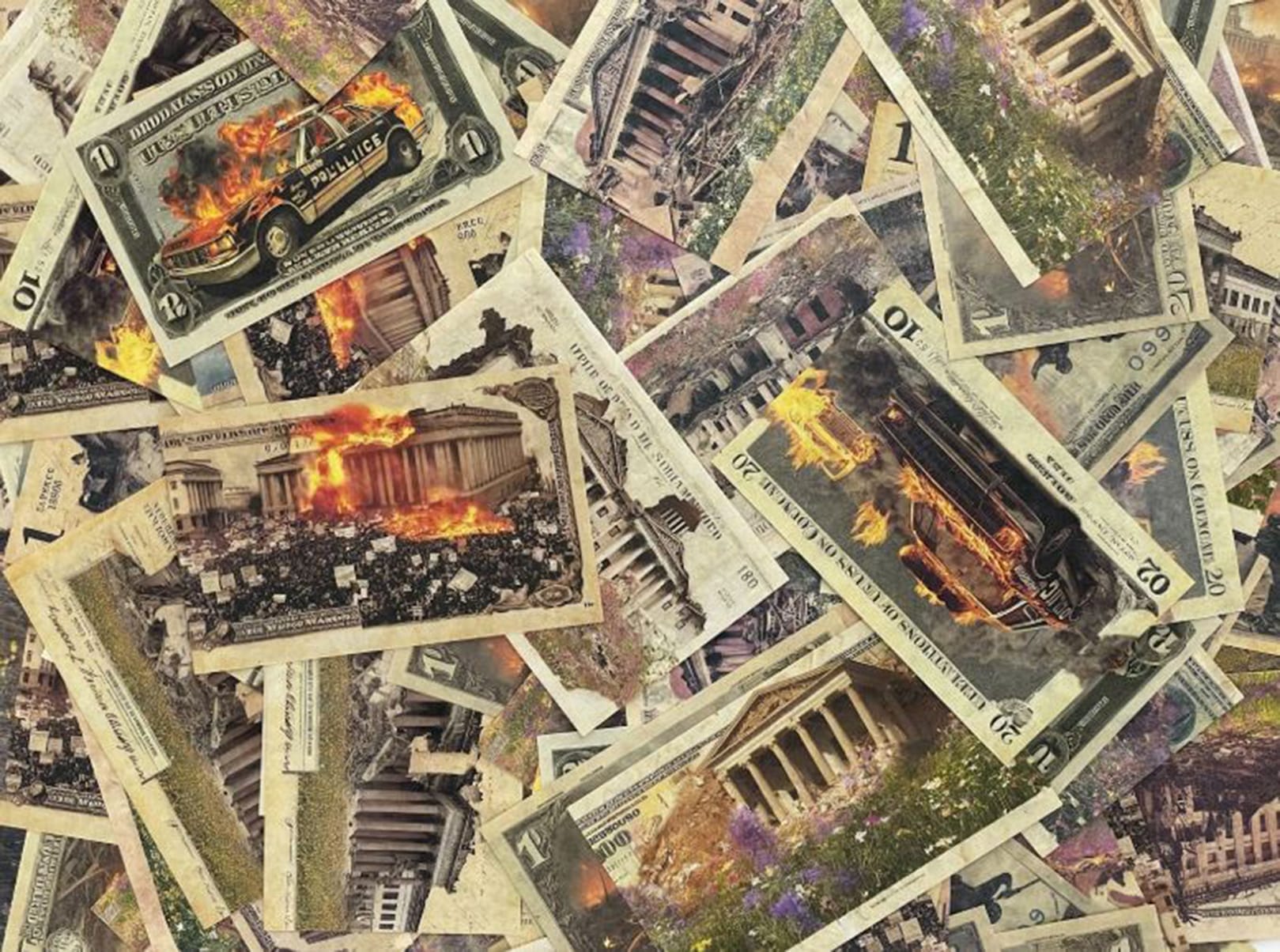

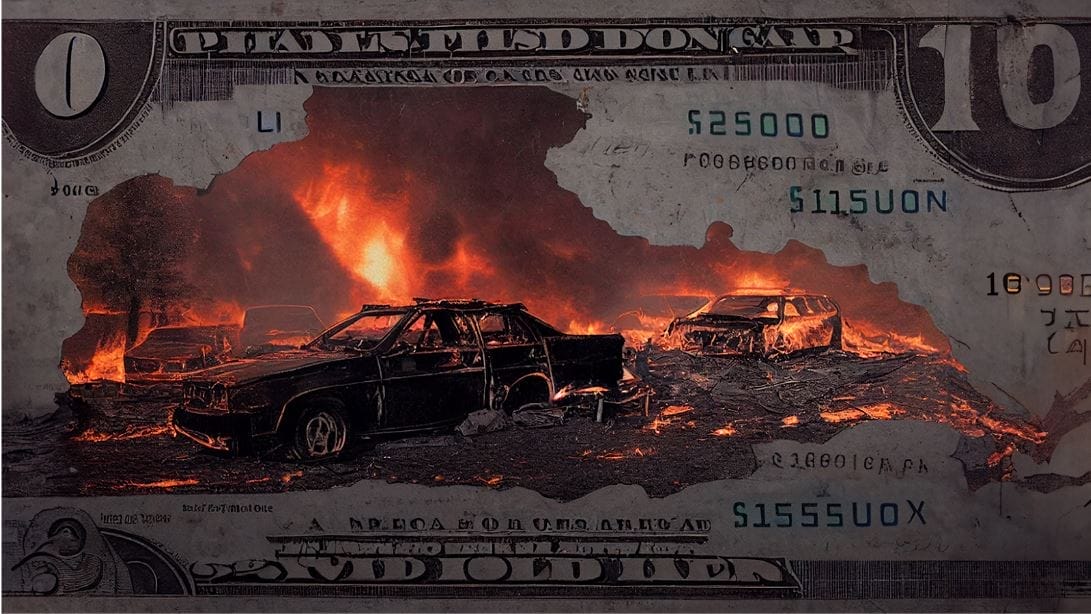

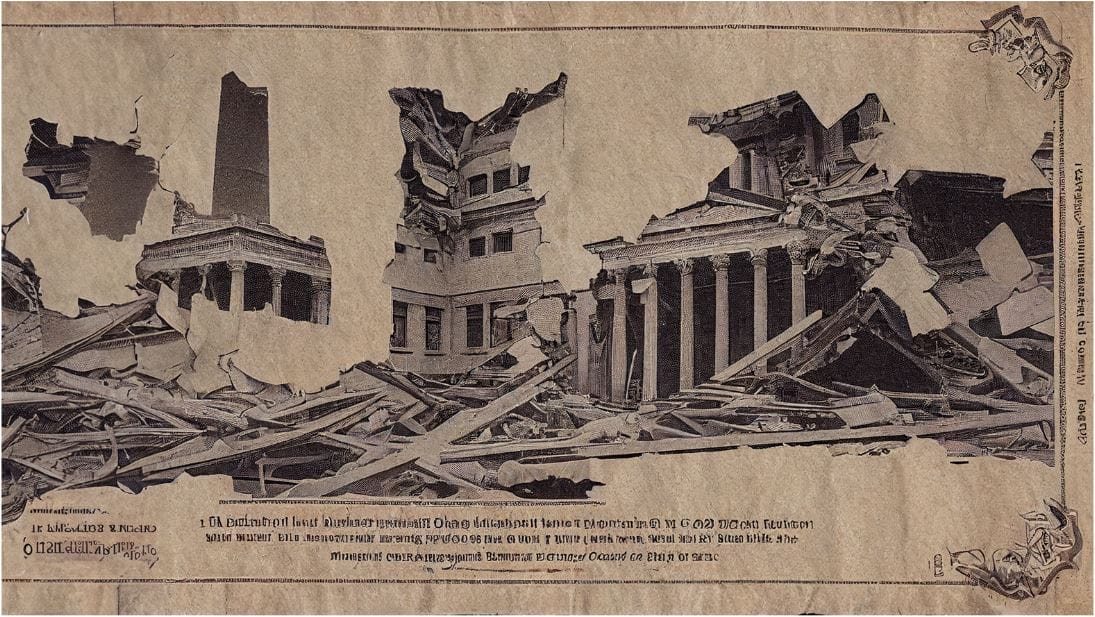

An even earlier example is my Currency of Protest series, my first AI work from 2022. I was using the earliest Midjourney models, but the work transcended the digital, it became a participatory installation. I printed those AI-generated images on seed paper so people could plant them and grow wildflowers. The physical and digital parts of the work totally depend on each other. That’s what excites me most: when a project exists in multiple states at once.

The exploration of virtual worlds is a significant part of your artistic practice. What attracts you to these digital spaces, and how do they influence your perception of reality and identity?

I think I was drawn to these spaces because they felt like truly unmapped territory. As someone who spent decades photographing the far edges of the physical world, I found myself fascinated by these parallel virtual worlds where hundreds of millions of people were inhabiting lands that most will never know exist.

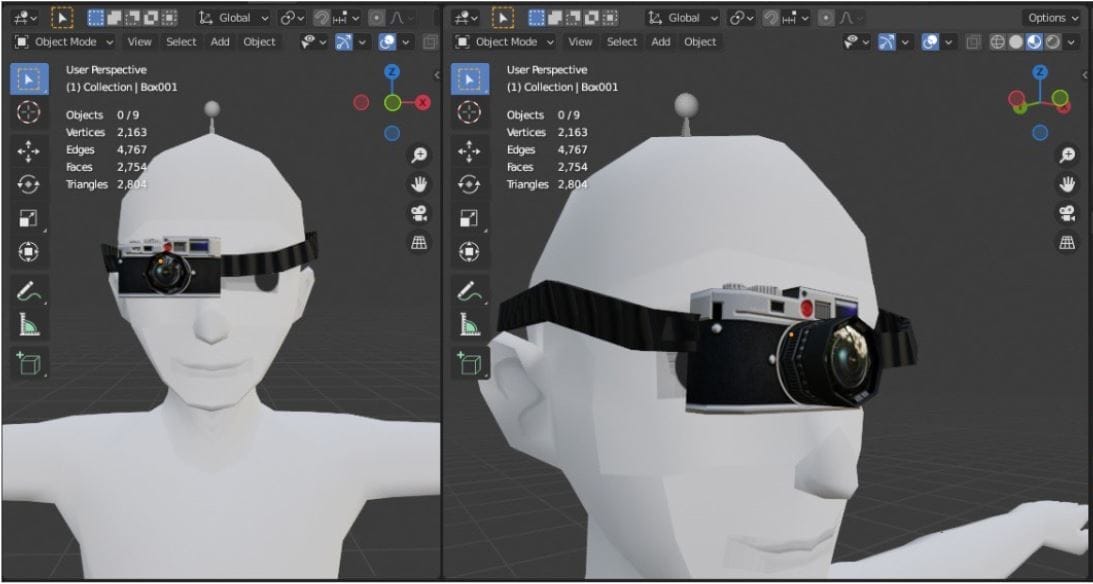

The attraction wasn’t just about documenting new spaces, it was a challenge to my understanding of identity. Each virtual environment required me to recreate myself in a new way. Sometimes this meant collaborating with a company to create a meticulously crafted digital twin that would be released across thousands of apps and virtual worlds, other times it meant becoming something completely conceptual, like in Cryptovoxels where I transformed into a walking 8×10 camera with tripod legs.

These experiences definitely shifted how I think about reality and embodiment. When photographing a meditation gathering where participants are physically scattered across the globe but intensely present together, or documenting a virtual birth that generates real emotional responses from witnesses, it questions what we mean by “real.” The boundaries between physical and digital existence become increasingly fluid.

What also makes these spaces particularly compelling is how they combine technical constraints with unprecedented freedom. Each world has its own rules and limitations, yet within those constraints, you can transcend physical laws – wading through molten lava with my custom avatar, for instance, or manipulating environmental conditions and lighting in real-time in Second Life. This tension between limitation and possibility creates entirely new territories for photographic exploration.

In your work, you often tackle the theme of boundaries, both physical and digital. How do you interpret the concept of “limits” in your artistic research?

I interpret “limits” not as fixed boundaries but as contextual and evolving, permeable thresholds to be explored and questioned. In my artistic research, limits are usually opportunities for transformation rather than endpoints. As I’ve moved from traditional photography in my youth, to a more post-photography practice, I’ve adapted to new technological paradigms while maintaining my core investigative approach. My work consistently examines the space between established categories, so I definitely see limits as provisional rather than absolute and I’m drawn to spaces where conventional understandings break down. High altitude peaks, the frontlines of conflict, nano scale exploration, the boundaries of virtual worlds – these are all sites where reality becomes more complex and nuanced because we are confronted with death or the unknown at a whole new scale.

The representation of the void and the unknown seems recurrent in your projects. How does this reflect the human condition and our relationship with technological innovation?

The void and unknown are the most rewarding places because they are the ultimate wells of knowledge and vision. The Belly of the Whale, the dark woods, death: these are the symbolic spaces of transformation, where new possibilities emerge and whole new worlds are birthed. It’s not quite that romantic when confronting the limits of technology, but it is still us butting our heads against new forms of unknowability with the hope of breaking through.

I first started photographing the far edges of virtual worlds in 2021 with my Edge Studies series. I wanted to capture the places where world builders stopped their construction—the frontiers where thought itself seemed to have reached its limit. In these borderlands I encountered invisible walls that halted avatar progress, unloaded landscapes suspended in digital limbo, and transitions where detailed world-building gave way to unrendered voids. By exploring the in-between, I could photograph through the “folds” of digital matter, offering glimpses into the skeletal framework of these constructed realities.

Once I had found the edges, I began to leap off of them. I turned the camera on myself, capturing my avatar suspended over digital voids across diverse virtual environments. The avatar poised at these boundaries becomes a metaphor for humanity’s constant push against the limits of the known, while the ability to defy physics highlights the profound differences between physical and digital existence. Through this performative act of leaping into the void, I could explore what it means to have a body in spaces where the rules of physical reality no longer apply.

Back to limits again: I suppose these kinds of explorations of digital boundaries reflect our fundamental human condition as beings who constantly push against limits. Throughout history, we’ve developed technologies to extend our reach, but each innovation creates new frontiers of unknowability. This paradox defines our relationship with technology: we build new territories to explore, then search for their edges, revealing our perpetual desire to venture beyond the known.

Collaboration is an important element in your practice, as seen in your project with your daughter Juno. How significant is it for you to involve others in your creative process, and what does it bring to your work?

What collaboration brings to my work is the beautiful tension between intention and surprise. There’s an unpredictability, a friction between, or flow with, different approaches that creates something truly new. When I involve others in my creative process – whether communities I’m documenting, other artists, or my daughter Juno – the result is always something I couldn’t have conceived alone.

With Nano Sketches, my daughter’s involvement transformed what had been a technically complex but conceptually straightforward project into something with much more emotional resonance. My solo exploration had become a meditation on deep time and cosmic insignificance, but Juno’s involvement grounded it in the immediate present, offering a human touch that made the incomprehensible somehow accessible.

I’ve seen similar transformations happen through my work with communities and in virtual spaces. The most interesting territory exists at these intersections, where multiple perspectives converge to create something unexpected. It’s a form of boundary crossing between generations, between disciplines, between worldviews that parallels my interest in exploring boundaries in physical and virtual spaces.

The use of artificial intelligence and other advanced technological tools is prominent in your work. How do you view the balance between artistic control and algorithm-generated results?

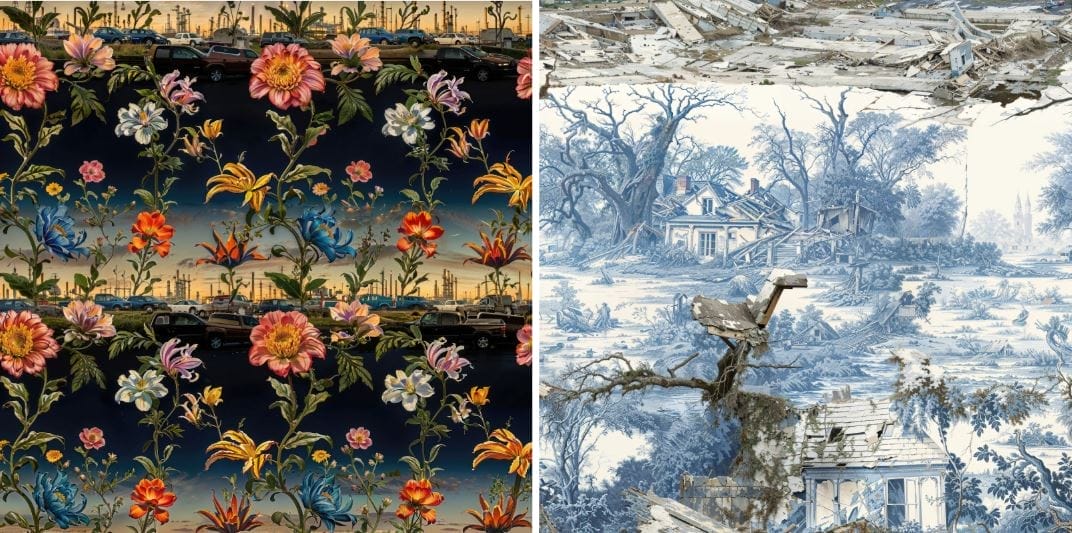

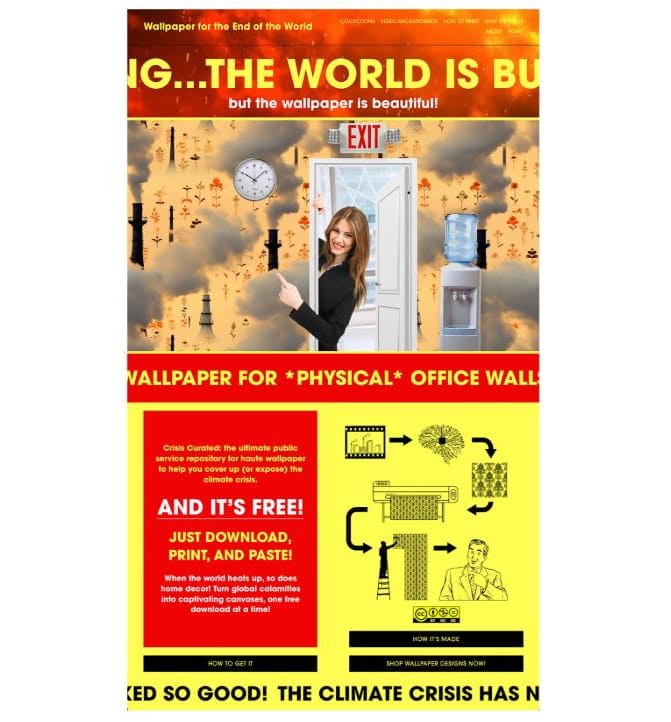

I approach AI as another kind of camera, a tool that can be directed but that also has its own way of seeing. I started my Wallpaper for the End of The World project in early 2023 (crisiscurated.com) because I wanted a way to make these AI outputs really feel like they were my photographs, not just a text-to-image exercise pulling all ingredients from others.

Starting with my image archive as the primary prompt, with only a single text addition for each piece (limited strictly to one historical wallpaper pattern name such as damask, chinoiserie, or toile de jouy, etc), I use a method that prioritizes visual content over verbal descriptions. This approach allows the generative AI to engage more directly with the visual language of my photography, bypassing the usual descriptive text prompts typical of text-to-image generation projects.

With Nano Sketches it was even more targeted and I had more control because it was a LoRA trained on my own archive wrapping my daughter’s drawings in the photographic attributes and light of my own images, preserving both the visual signature of my photographs and the essence of her own creativity. So there is great balance and still the lottery of chance that happens when we run imagery through any diffusion model.

I find this balance between direction and unpredictability to be creatively generative. Using custom models trained on my own visual language creates a feedback loop with my artistic history. The algorithm sometimes reveals patterns and possibilities in my image-making that I hadn’t consciously recognized, creating a dialogue with my own past work.

With projects that transform images of crisis into aesthetic elements, how do you balance aesthetics with the urgency of the messages you wish to convey?

Aren’t we always transforming crises into aesthetic elements with art? We’re always wrestling with one crisis or another.

If I think back to documenting the results of the North American genocide of native peoples, at its core, I’m making beautiful images of horrible things. The same is true of Wallpaper for the End of the World, making beautiful wallpaper patterns of the climate crisis. And sometimes that’s all we can do as artists. If we’re not controlling the political landscape or holding administrative power, then we are working in that absurd realm of beautifying stories of the crises around us.

I found an interesting parallel with historical decorative arts from the 18th century, when wallpapers and tapestries told stories about empire, commerce, and environmental change. They turned scenes of colonization into beautiful repeating patterns for wealthy homes. I’m doing something similar but inverted: taking our contemporary crises and transforming them into wallpaper patterns that can inhabit domestic spaces while carrying their uncomfortable truths. The aestheticization isn’t about making these crises more palatable. It is about finding new ways to make people live with these urgent realities in their daily spaces.

How do you see the role of the photographer evolving in the digital era, especially with the integration of algorithms and virtual reality into the creative process?

As we move further into the digital age, the idea of the “lens” is no longer confined to capturing light through a piece of glass. Lenses and cameras have become exponentially more sophisticated, embedded with, interpreting, and even created from complex algorithms. I think of my archive itself as a new kind of lens, one that allows me to untether from the singular decisive moment and enter an ongoing process of exploration and creation. All of this challenges traditional definitions of photography.

Traditional photography captures what is and was, but these new tools allow us to explore what was not, what cannot be, or what could be in some future or alternate world. It’s not about replacing traditional photography but expanding what’s possible. We are moving into an era where photographers, where all artists, would benefit from being fluent in multiple realities, physical, virtual, and synthetic.

Your artistic practice seems to create a “hybrid reality” that converges past and future. How is this fusion reflected in your works, and what do you hope the audience takes away from it?

Yes, especially with projects where my past photographic work is either the seed or the whole model. That work with my archive has become a way of time traveling and stitching together realities across time. For instance, when I look back at my Hurricane Katrina images from 20 years ago, I am able to return to that moment, to turn my head in another direction through AI tools, to look around inside the event again. This approach allows me to re-examine moments I’ve already traveled to but with a new perspective. When I look back at bodies of work from early in my career, I can see what my less-developed photographic eye missed. Going back with these tools, I can re-enter those moments and re-photograph them, creating a dialogue between my past and present artistic selves.

I think this hybrid approach, where we can simultaneously explore what was documented and what was not, reflects our current moment perfectly. When I use these tools to reinterpret my climate crisis archive or create new visions from old documentation, I am creating spaces where multiple realities can coexist.

What I hope audiences take away is a heightened awareness of the fluid nature of time, memory, and documentation. These works invite viewers to consider reality not as a fixed narrative but as layers of possibilities upon one another. In traditional photography, we’re bound to the decisive moment – the singular instance frozen in time. But these hybrid works exist simultaneously across multiple moments, challenging the notion of a singular, authoritative version of events.

As the founder of Amplifier.org, you’ve collaborated with artists on global campaigns that question power and amplify movements. How has this experience influenced your personal approach to art and curation?

Amplifier has been an important chapter in my life as a person who cares about, and wants to affect the course of, events in the world, but it is a separate practice from my personal art practice. The organization emerged organically when my documentary work had reached a point where it needed to change shape to reach more people, which was when I first reached out to Shepard Fairey to start what has become 14 years of collaboration now.

The impact of that experience funding and art directing in the trenches of resistance movements is definitely visible in projects like Currency of Protest and Wallpaper for the End of the World. Both have free distribution paths in physical form for the currency and as high resolution downloads meant to literally turn into wallpaper at crisiscurated.com. Being constantly exposed to in-depth dialogue about social and environmental crisis and the communities being actively harmed has informed my conceptual frameworks and distribution strategies, and heightened my awareness of how images function in different contexts.

The work has sharpened my understanding of the tension between aesthetics and urgency that we discussed earlier. In the advocacy space, the primary goal is impact and message clarity, while in my personal practice, I can explore more ambiguous and complex relationships with similar subject matter. This dual perspective has allowed me to consider how images transform as they move between contexts – from protest signs to gallery walls, from direct messaging with Agitprop, to more oblique artistic inquiry.

There’s a pattern that continues through all my work: recognizing when established forms have reached their limits and finding new collaborations or modes of expression and distribution to transcend those boundaries.

fakewhale

Founded in 2021, Fakewhale advocates the digital art market's evolution. Viewing NFT technology as a container for art, and leveraging the expansive scope of digital culture, Fakewhale strives to shape a new ecosystem in which art and technology become the starting point, rather than the final destination.

You may also like

Bridging the Divide: The Struggles of Digital Art in the Traditional Art World

In an increasingly digital age, the art world finds itself at a crossroads, grappling with a questio

Sculpting Society: The Unfinished Revolution of Joseph Beuys

Origins of a Myth: The Body, the War, the Transformation To speak of Joseph Beuys is to enter immedi

11 – The United States of Grain Alcohol

White House, Washington D.C., United States President Knudson paced around his office. If you could