Cutting Through the Conventional: The Radical Art and Vision of Gordon Matta-Clark

The Architect of Anarchitecture

Gordon Matta-Clark, born in New York in 1943, is an emblematic figure in the 1970s art scene, renowned for his revolutionary approach to architecture and sculpture. The son of a well-known Chilean surrealist painter, Roberto Matta, and an American artist, Anne Clark, Matta-Clark inherited a profound artistic sensibility that shaped his unique and radical vision of art and architecture.

After earning a degree in architecture from Cornell University in 1968, Matta-Clark began exploring the intersections between art and urban space in ways that had never been considered before. Unlike his contemporary architects, he was not interested in constructing new buildings but rather in transforming existing ones through what he called “anarchitecture.” This term, coined by him, reflected his critique of conventional architectural norms and his interest in the city’s abandoned structures and forgotten spaces.

Matta-Clark’s artistic practice was deeply rooted in a philosophy of direct intervention, which saw the artist making cuts, slices, and removals on buildings slated for demolition. His most famous work, “Splitting” (1974), involved literally cutting a two-family house in Englewood, New Jersey, in half. Using circular saws and other heavy equipment, he removed a central vertical section of the building, exposing the internal parts that would normally remain hidden. This act of “cutting” transformed the building into a living artwork, exploring light, space perception, and temporality.

His works were not only physical expressions but also powerful socio-political statements. Through his art, Matta-Clark commented on urban destruction, alienation, and abandonment, reflecting on the life cycle of urban spaces and the impact of human activity on the built environment. He saw his work as a way to give a voice to the forgotten and neglected spaces, inviting viewers to reflect on the transience and reconfiguration of urban spaces.

Gordon Matta-Clark was a pioneer in his field, and his work continues to influence contemporary artists and architects. His vision extended the field of architecture far beyond traditional boundaries, introducing new dimensions of social critique and spatial interaction that still challenge our concepts of space and structure today.

Visions of Space and Community

In the 1970s, New York City’s urban landscape provided Gordon Matta-Clark with a living laboratory for experimenting with and implementing his anarchitectural theories. Among his most significant projects from this period was “Food,” an artist-run restaurant opened in 1971 in the heart of SoHo, a neighborhood then undergoing deindustrialization and transformation. “Food” was not just a place to eat, but a social and artistic installation, a gathering point for the emerging art community where dialogue and the exchange of ideas were as much a part of the menu as the innovative dishes served.

Matta-Clark saw “Food” as an expression of his critique of the commercialization of urban space and a way to reconnect everyday life with art. The restaurant thus became a form of “process art,” emphasizing the importance of human relationships and creative collaboration in the act of making art. Through this initiative, Matta-Clark not only challenged artistic conventions but also rewrote the rules of community engagement and urban space.

Concurrently, Matta-Clark continued to explore the concept of physical space through projects like “Conical Intersect” (1975), executed in Paris as part of the Paris Biennale. In this work, he cut through two adjacent seventeenth-century buildings slated for demolition to make room for the Centre Pompidou. This intervention created a visual cone that passed through the buildings, allowing new visual perspectives and radically transforming the experience of urban space. With this act, Matta-Clark not only questioned the permanence and value of historical spaces but also the political and economic decisions that shape the urban environment.

Matta-Clark’s approach to art as a tool for social inquiry and as a catalyst for change was also evident in his photographic and film projects. He meticulously documented his interventions and their interactions with the surrounding environment, creating a visual archive that served both as documentation and as an extension of his artistic practice. These works, which often included filmed sequences of his structural cuts, invited viewers to look beyond the physical surface of urban spaces and reflect on their history, use, and transformation.

Through these explorations, Matta-Clark not only drew new mappings of urban space but also redefined the role of the artist as an active agent in the social and cultural fabric of the city. His vision of common spaces transformed into sites of artistic interaction continues to influence contemporary practices in the fields of art and architecture, demonstrating the power of art to provoke reflection and change.

Segmented Spaces

Gordon Matta-Clark’s artistic practice reached new heights with his radical and experimental approach to segmented spaces. One of his most revolutionary projects in this area was “Day’s End” (1975), a work that highlighted his ongoing interest in the interplay between light, space, and perception. Matta-Clark transformed a massive abandoned warehouse on a New York pier into a colossal light installation. He cut large openings in the walls and ceiling of the warehouse, creating a play of light and shadows that changed with the movement of the sun, turning the entire structure into a temporary and dynamic sundial.

This project not only altered the physicality of the warehouse but also its perceptual and symbolic experience. Matta-Clark used the abandoned space not just as a canvas but also as a medium to explore temporality and transience. The title of the work, “Day’s End,” reflected the ephemeral nature of the installation and his meditation on endings, both in terms of a day and of a bygone industrial era. With these large openings, he transformed the warehouse into a place for reflection on light and time, inviting the audience to consider new possibilities for forgotten urban spaces.

In addition to his large-scale interventions, Matta-Clark was deeply engaged in documenting the processes and effects of his work. His photographs and films not only served as documentation of his temporary works but also became artworks themselves. For example, the film “Day’s End” documents the cutting process of the work of the same name, offering an intimate view of his work and philosophy. These documentaries, projected in galleries and museums, extended the life of his installations beyond their physical existence and allowed a broader audience to experience his radical interventions.

Matta-Clark was also an active theorist, and his reflections on space and architecture were deeply intertwined with his artistic practice. His notes, sketches, and correspondence reveal a profoundly philosophical and critical thinking about modern urban life and its discontinuities. Through his art, he sought to dismantle not only physical structures but also the conceptual barriers between different disciplines, proposing an integrated and multidimensional vision of art, architecture, and everyday life.

With “Day’s End” and other similar projects, Matta-Clark not only challenged traditional conceptions of space and structure but also extended the dialogue on art and its capacity to influence and reflect cultural and social changes. His legacy continues to influence generations of artists and architects, pushing them to consider new interpretations of space and its transformative potential.

Matta-Clark also had a significant impact on the debate surrounding the preservation, reuse, and transformation of urban spaces. His works, often created in abandoned buildings or disused areas, prompt reflection on issues such as sustainability, urban planning, and social responsibility. Today, Matta-Clark’s legacy is evident in the practices of artists and architects who see value and potential in urban remnants and decommissioned structures.

In conclusion, Gordon Matta-Clark was not just an artist who worked with spaces, but a visionary who reinterpreted the role of the artist in society. With a legacy that continues to influence and inspire, Matta-Clark remains a central figure in discussions about the nature and possibilities of modern art. His works, ideas, and pioneering spirit live on in ongoing dialogues and practices that challenge and expand our understanding of art and space in contemporary life.

fakewhale

Founded in 2021, Fakewhale advocates the digital art market's evolution. Viewing NFT technology as a container for art, and leveraging the expansive scope of digital culture, Fakewhale strives to shape a new ecosystem in which art and technology become the starting point, rather than the final destination.

You may also like

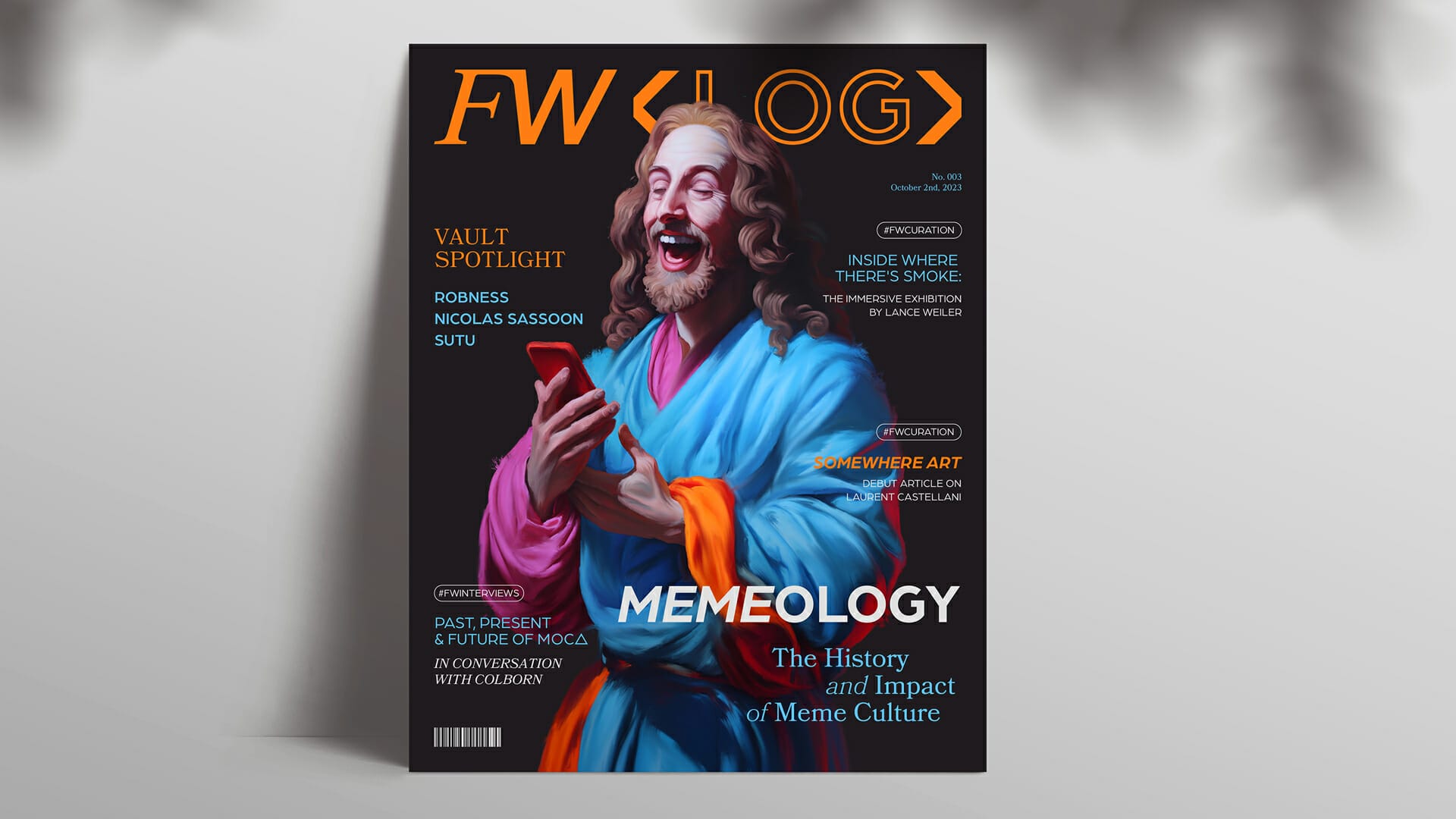

FW LOG: Editorial Feed No. 003

The FW Editorial Feed No. 003 meticulously explores the dynamic interplay of diverse expression and

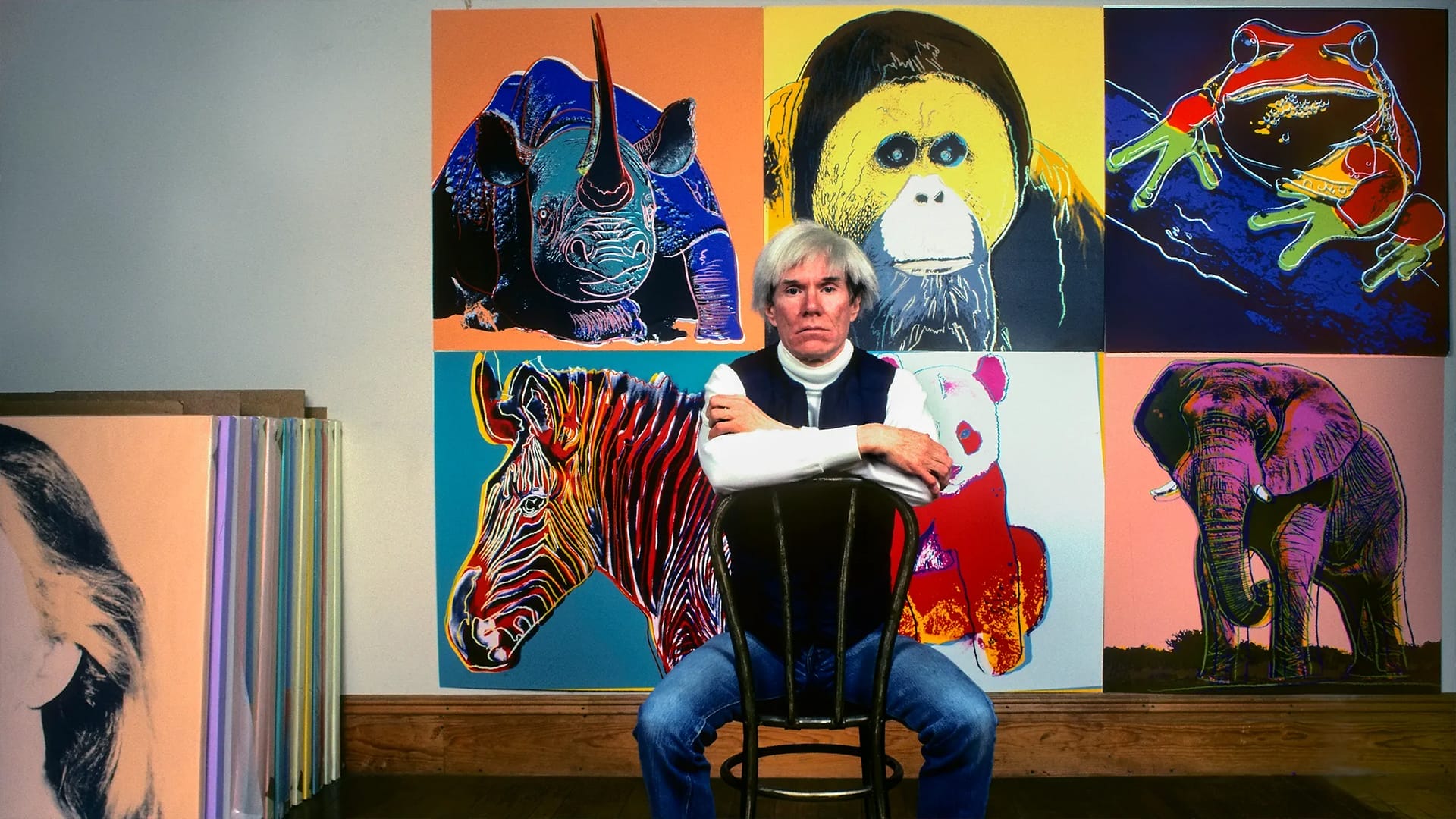

The Warhol Effect: We Are All Sons of Andy

A Pittsburgh-born artist, Andy Warhol emerged as one of the most recognized artists in the 1960s New

A Cubicle, Terminal at Schwindel LLC, Vienna

A Cubicle, Terminal by Morgane Billuart, Meltem Rukiye Calisir, Xin Huang, Martin Rovan, Paul Seipel