Between Prom Nights and Protest Signs: Anne Imhof’s DOOM House of Hope at the Park Avenue Armory

We at Fakewhale followed the buzz around Anne Imhof’s much-anticipated return to New York, where her new major U.S. production, DOOM: House of Hope, took over the Park Avenue Armory. The German artist, who won the Golden Lion at the 2017 Venice Biennale with Faust, is no stranger to controversy (think of DEAL at MoMA PS1 in 2015, when live rabbits onstage disconcerted American audiences). This time, she has orchestrated a massive, immersive “superscore” incorporating more than fifty performers: skaters, actors, musicians, and ballet dancers among them.

A Hyperreal America

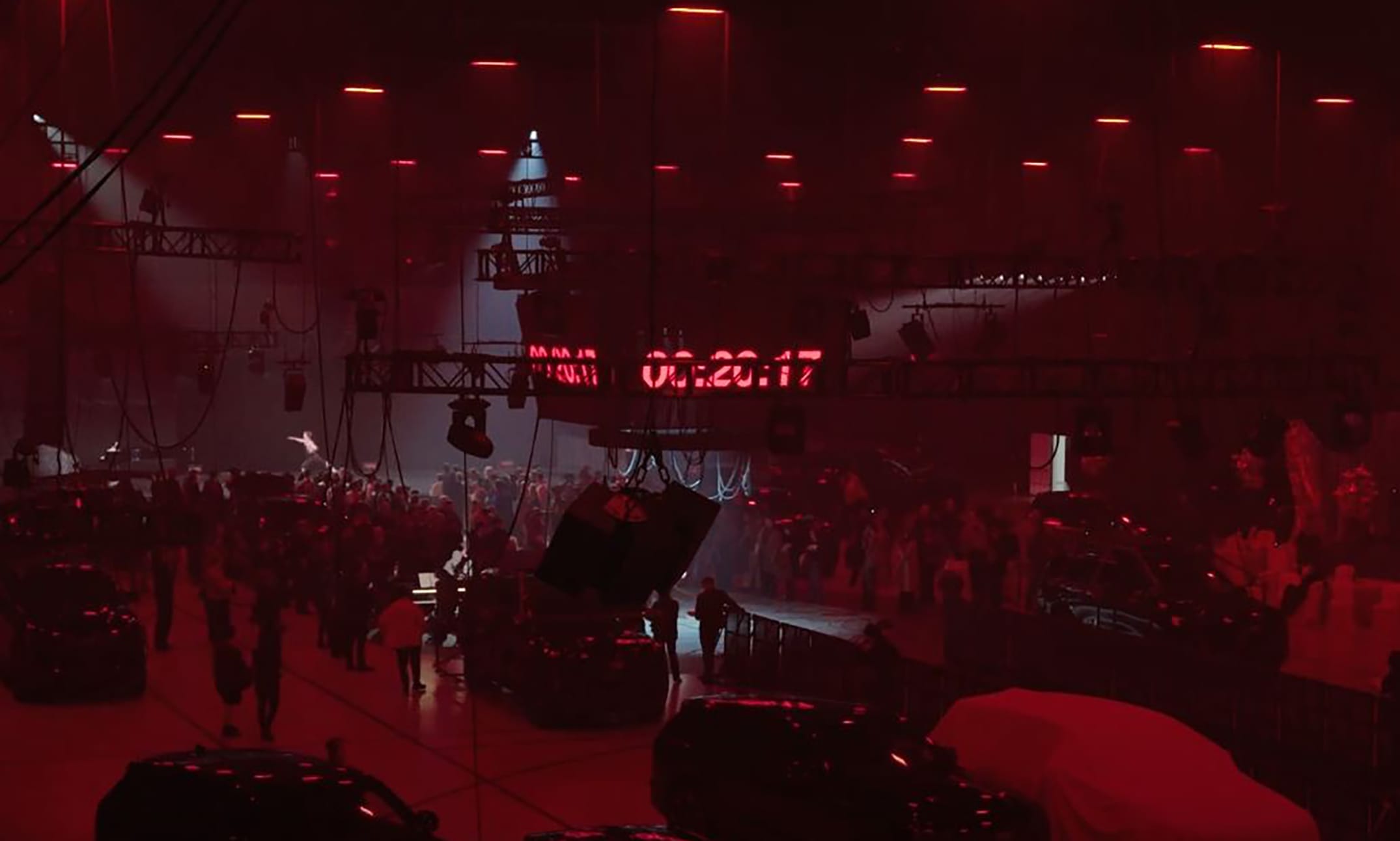

As soon as we entered the vast Wade Thompson Drill Hall, we found ourselves in a setting reminiscent of a quintessential American high school movie: a gym-sized armory with movable barriers, a “prom party” installation complete with silver balloons and decorated tables, and rows of gleaming Cadillac Escalades. This dystopian American dreamscape was made even more surreal by the controlled darkness, occasionally broken by spotlights glinting off metal surfaces. Imhof, who has long demonstrated a knack for captivating and unsettling audiences, seems intent on directly engaging with iconography typical of the United States, as though seeking a bridge between her own artistic vocabulary and the references most familiar to New Yorkers.

The Feeling of Being Locked In

Inside the vast Wade Thompson Drill Hall, the atmosphere conjures images straight out of a quintessential American high school movie: a gym-like space dotted with movable barriers, a “prom party” setup complete with silver balloons and bedecked tables, and rows of gleaming Cadillac Escalades. The dystopian dreamscape is heightened by controlled darkness, pierced only by sharp spotlights glinting off metal. Known for her ability to captivate and unsettle, Imhof seizes on iconography linked to the United States, bridging her own aesthetic language with visuals immediately recognizable to New Yorkers.

Stretched-Out Time

A defining feature of DOOM is its sense of time. Imhof has installed a Jumbotron that counts the minutes, though this does not build suspense in the typical way, instead reminding us that the performance lasts three hours and emphasizing its slow, repetitive pace. It is not necessarily an attempt to exhaust the audience, or at least not only that. It is an invitation to actively explore the space, to choose where to go and when to move on, following each person’s own rhythm. Some moments fly by, like the gentle scene in which Eliza Douglas (a long-term Imhof collaborator, here bridging music and performance) sings “We Can” with such intensity that she ends up giving a rare smile, breaking the show’s veneer of total indifference.

Among those luxury vehicles, we stumble on cardboard signs covered with political slogans, calls for trans rights, and demands for freedom against fascism and discrimination. This explicitly political element stands in stark contrast to the show’s apparent detachment, adding another layer of interpretation: on one side, performers projecting a “cool” indifference, on the other, the harsh reality of protest scrawled on humble cardboard. You cannot help but wonder if this contrast is deliberately highlighting the distance between privileged social circles and more marginalized communities, especially in a historical moment when identity politics are a hotly contested battleground, particularly in the United States.

Art as a Space of (Ex)Inclusion

Imhof offers us no definitive reassurance or solution to the tension between inclusion and exclusion. Indeed, her background itself, which includes a stint as a bouncer in a Frankfurt club, speaks to her history on the “outside.” Even so, this time she plays with American scenography and contemporary dance, with prom-night imagery and youthful rites, blending them with her signature artistic language: vacant stares, almost sculptural poses, and performers seemingly disconnected from the concept of an audience.

The deeper we ventured into DOOM: House of Hope, the clearer it became that the artist has also opened up to fresh possibilities. There are moments of collective singing, ballet passages that nod to Faust and Angst in a less esoteric, more theatrical key. In the last 45 minutes, the emotional intensity really ramps up as the performers almost “break down,” showing bursts of anger and fatigue as if something cracks beneath their façade of cool detachment.

By the time you exit the Park Avenue Armory, it is impossible not to sense both the monumental and intimate aspects of DOOM, a piece that can feel detached yet intermittently charged with emotion. Rather than delivering a straightforward political message or a tidy story, Imhof leans into ambiguity and disorientation. Some sections unfold with a chilling stillness, while others brim with warmth, suggesting the artist is testing a new kind of hope, if one is willing to recognize the complexities of our moment.

DOOM is ultimately a journey that leaves you feeling both privileged and trapped, a spectator who may also become an unwitting participant. Its most explosive power lies in resisting easy answers. In that blurred space between spectacle and self-reflection, contemporary art can still jolt us awake. Whether mesmerizing or perplexing, Anne Imhof’s DOOM: House of Hope ensures it won’t be easily forgotten. And if the questions it raises remain unanswered, perhaps that is where its potency truly resides…reminding us, much like Shakespeare’s tragedies, that art rarely offers a single truth. It simply holds a mirror to our uncertainties, imploring us to look closer.

fakewhale

Founded in 2021, Fakewhale advocates the digital art market's evolution. Viewing NFT technology as a container for art, and leveraging the expansive scope of digital culture, Fakewhale strives to shape a new ecosystem in which art and technology become the starting point, rather than the final destination.

You may also like

Fakewhale in conversation with Franc Archive

Coming from a background in street art and now working across digital installations and performative

Jean-Baptiste Durand in conversation with Fakewhale

Jean-Baptiste Durand moves fluidly between design, ceramics, and scenography, merging industrial and

WUF Basel 2024: Solo Press Showcases Curated by Fakewhale

On June 11-12 WUF will be hosting an invite-only event for the press at Bar Rouge, Messepl. 10 Basel