Painting After the Machine: Wade Guyton and the Aesthetics of Reproduction, Error, and Withdrawal

The Computer in the Empty Room

There are moments in the trajectory of certain artists that feel like extended silences, not absences, but suspensions. As though the work itself were waiting to be thought before it could be made. Wade Guyton emerged in the American art system at the turn of the millennium, a time when strong narratives had already been exhausted. Painting had been declared “dead” more than once, and digital tools were beginning to infiltrate the creative process without yet claiming any aesthetic authority. There was no manifesto, no movement. Just a computer, an Epson printer, and an empty room.

Born in Hammond, Indiana, in 1972, Guyton moved to New York after his studies, working as an editor at Harper’s, an environment far from the gallery world but saturated with a quiet, latent visual sensitivity. It was there that he began producing his earliest works using tools that, at the time, seemed entirely unremarkable: Microsoft Word, a flatbed scanner, a consumer inkjet printer. The story goes that his inaugural gesture was almost incidental, a large black “X” printed onto a white page, repeated, shifted, overlaid. And yet in the blind repetition of that typographic mark, a foundational act was taking place: no longer painting, no longer image, but a systematic error turned into style.

Guyton does not paint. Nor does he “design” in the modernist sense. He establishes, instead, a method of production that lives inside a malfunction: the printer, built to produce spreadsheets, contracts, clean layouts, is overloaded, forced, made to fail. The smudges, misalignments, cut-off blocks of ink, these are not flaws to be corrected but signatures of an internal resistance. In this way, Guyton’s art is born as a strategy of sabotage from within the device.

His first significant solo show came in 2005 at Friedrich Petzel Gallery, but the critical response had already been percolating. Earlier works, pages torn from art magazines, overwritten with black bands or emptied-out words, had drawn attention from those attuned to the new aesthetic signals. At a time when the art world was still metabolizing the legacy of 1980s appropriation, Guyton proposed something else entirely: a form of painting that prints itself, that refuses construction, that doesn’t represent but instead registers a break.

That empty room, with the computer and the printer, was not a studio in the traditional sense. It was a zone of tension, an interface between the artist’s body and the automated logic of the machine. From that space emerged a practice that, without declarations, began to redraw the coordinates of art-making. The artwork was no longer an object or a surface, but a field of programmed failure. And from that first failure, everything began.

Printing the Gesture

To speak of gesture in the context of Wade Guyton is to confront a paradox. The term, historically tied to the expressive impulse of the artist’s hand, Pollock’s drip, Twombly’s scrawl, Kline’s slash, finds itself displaced, if not entirely disarmed, in Guyton’s work. And yet, the gesture does not disappear; it mutates. In his practice, the gesture is printed.

The black “X,” recurring like a stutter across his early works, is neither a symbol nor an abstraction, it is a mark without metaphor, a gesture performed not by a wrist or brush but by the read head of a consumer-grade inkjet printer. Still, it retains a strange urgency. The ink, dragged across the page or canvas, bleeds and stutters in places where the machine hesitates. Misfeeds, jams, folds, and overlaps become sites of meaning. In this mechanical choreography, intention and accident are indistinguishable.

What Guyton offers is a model of authorship that bypasses expression and enters into conflict with execution. The file is prepared—Word documents filled with monochromes, cropped images, letterforms—and then sent to print. But between digital preparation and material realization lies a narrow, volatile space: the moment when the canvas, fed manually into the printer, shifts or resists, when ink pools or skips, when data becomes matter through failure. It is precisely there, in that moment of breakdown, that the work acquires its singularity.

The art historical implications are both subtle and seismic. Guyton’s printed paintings, especially those large-scale U-shaped forms and flame motifs—echo the visual language of modernism, but with none of its metaphysics. They are, in many ways, after-images of minimalism: formal, repetitive, severe. But whereas Donald Judd sought to eliminate the hand to achieve objectivity, Guyton eliminates the hand to let in contingency. He does not manufacture precision; he exposes the limits of its pursuit.

Moreover, the gesture here is not only technical, it is conceptual. By outsourcing mark-making to a non-art device, Guyton inserts the machine into the lineage of painting not as a tool, but as a collaborator, and perhaps even a critic. The printer is not simply a surrogate for the brush; it is a site of resistance, a medium that pushes back.

In an age where the digital is often equated with smoothness, perfection, and infinite reproducibility, Guyton’s work insists on the friction between code and body, between data and dirt. His paintings do not celebrate technology; they complicate it. They are, above all, documents of a process in which control is rehearsed and relinquished simultaneously. The gesture, in this system, is not expressive, it is procedural, wounded, and printed with intention toward its own instability.

Ghosts of the Grid

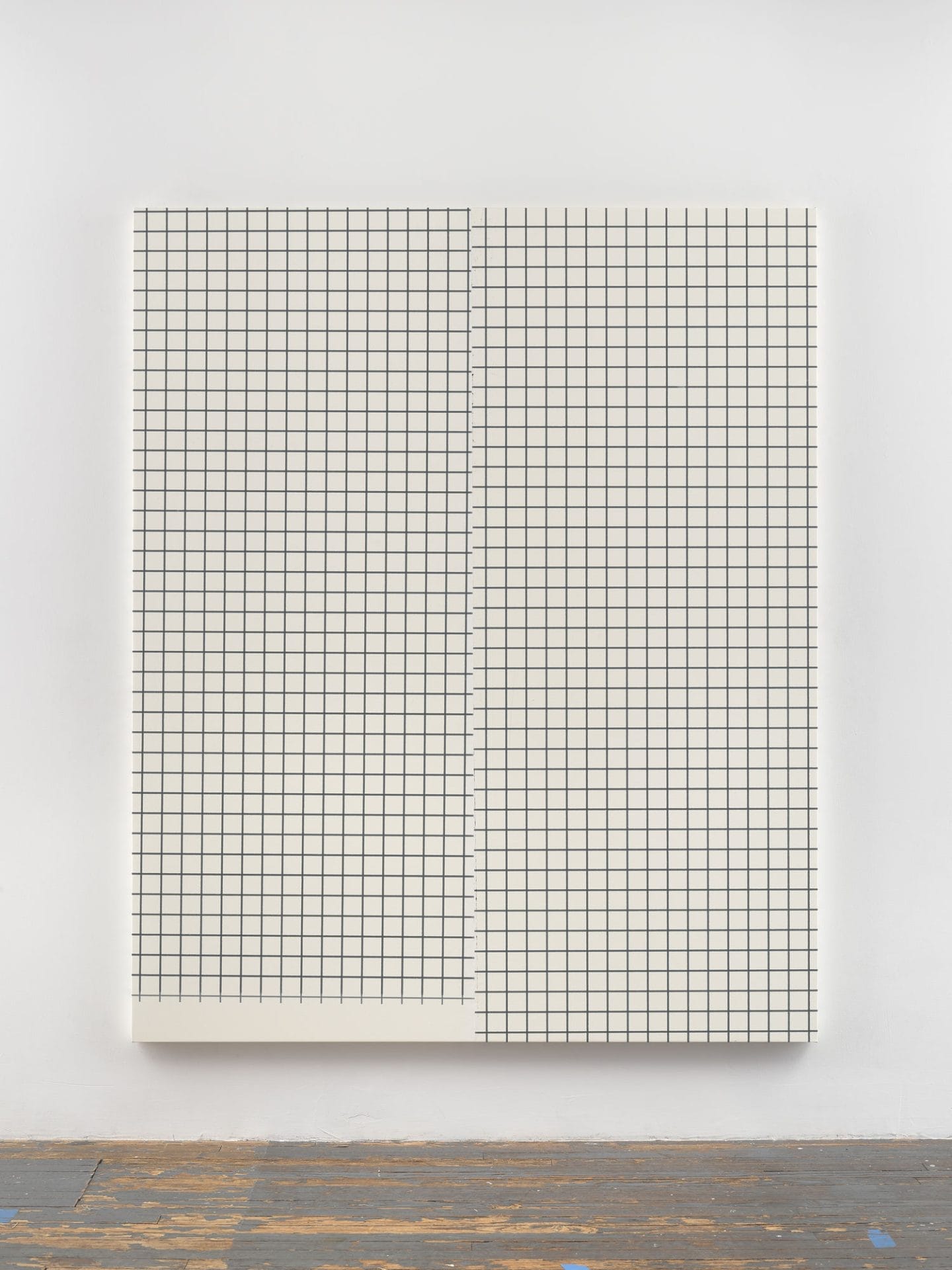

To approach Wade Guyton is to walk through the ruins of a system, one composed of orthogonals, seriality, neutrality. The grid, that foundational structure of modernist painting, reemerges in his work not as schema or ideology, but as a ghost. Haunting, fractured, no longer secure.

There is something uncanny in the way Guyton reactivates the grid. In the legacy of modernism, the grid had been both formal tool and metaphysical claim. In Rosalind Krauss’s famous reading, it was a declaration of autonomy, an ahistorical, anti-narrative field that severed the image from illusion. But by the time Guyton engages with it, the grid is no longer sacred; it is historical, compromised, and already saturated with meaning. And yet, he doesn’t discard it—he inhabits it with a sense of irony and critical fidelity, like a tenant refusing to pay rent on an abandoned property.

His repeated use of vertical stripes, symmetrical layouts, and axial alignments echoes the visual programs of Frank Stella, Agnes Martin, and even Mondrian. But the resonance is strained. Where Martin’s grids tremble with spiritual intensity, Guyton’s are deliberately indifferent. Where Stella’s paintings assert industrial control, Guyton’s surrender to technological fragility. The grid, in his hands, is not a utopian scaffold; it is a formatting error.

This spectral return is crucial. Guyton’s engagement with the history of abstraction is neither homage nor parody, it is an excavation. The grid survives, but it has been scanned, compressed, printed on canvas with inkjets not designed for such tasks. It is riddled with noise: micro-misalignments, ink bands, pixelated traces. The formal order it once promised now flickers, destabilized by the materiality of contemporary tools.

More importantly, the grid in Guyton’s work is no longer isolated within the domain of painting. It bleeds into screens, software, architecture. The Word document he uses as a compositional interface imposes its own invisible structuring logic, margins, alignments, font metrics, ghost-grids that infiltrate the aesthetic surface. In this way, Guyton extends the field of the grid beyond modernism and into the infrastructures of everyday digital life.

What we encounter, then, is a grid that no longer holds the world at bay, but lets it in. Smudged, burnt, misprinted, it becomes a site of permeability. Through this collapse, Guyton stages a quiet but profound institutional critique. He shows that the minimalist ideal of order was always entangled with mechanisms of control: technological, epistemological, even ideological. By printing the ghosts of those forms with cheap ink and corrupted files, he doesn’t just undermine their authority, he reanimates their unresolved contradictions.

The ghosts of the grid do not speak in Guyton’s work. They stutter. They misalign. And in that stuttering, we begin to hear something else entirely: not the voice of modernism, but its afterimage.

Pictures, after Pictures

In Wade Guyton’s work, the image is no longer a window nor a mirror—it is an echo. An echo of images past, compressed, degraded, reinterpreted through a process that neither photographs nor paints, but rather reproduces reproduction itself. This recursive condition, a picture of a picture, printed from a file, derived from a scan of something once material, marks a decisive shift in the ontology of the image. It is no longer what we see, but how we see through what has already been seen.

Guyton operates within a post-photographic landscape where the indexical power of the photograph has been eroded. The image does not bear witness to a moment in time; it carries no empirical guarantee. Instead, it circulates. His use of pre-existing imagery, pages torn from Artforum, JPEGs of flames sourced from Google, book scans of Frank Stella’s paintings, reveals an aesthetics of mediation. These images are already once-removed, twice-processed, flattened into data. What he adds is not interpretation, but friction.

Printing these images onto canvas, Guyton subjects them to a process of material contradiction. Ink streaks, banding errors, incomplete passes, these become the new expressive marks, replacing brushstrokes with machine artifacts. In doing so, he doesn’t just comment on the mechanical nature of image-making in the digital age; he embeds it into the structure of the work itself. The image, under his hand, is no longer an illusion to be looked at but a surface to be examined, decoded, distrusted.

The title of this chapter deliberately invokes Pictures, the seminal 1977 exhibition curated by Douglas Crimp, where the first generation of postmodern artists—Sherman, Prince, Longo, Levine—foregrounded appropriation and questioned the stability of representation. Guyton belongs to a generation shaped by that legacy, but he moves beyond it. Where appropriation artists treated images as signs to be quoted and critiqued, Guyton treats them as corrupted files, subject to degradation not only of meaning, but of code. He is not recontextualizing; he is reprocessing.

In this sense, his work is not just post-medium; it is post-surface. The traditional dichotomy between figure and ground collapses into a matrix of digital overlays. Flames float atop blankness; letters bleed into white; photographs of sculptures become patterns of ink error. There is no hierarchy, no focal point—only layers of data competing for visibility. And through that competition, a new kind of pictorial space emerges: one shaped not by light and shadow, but by compression artifacts and page alignment.

To encounter a Guyton canvas is to witness the slow exhaustion of the image’s authority. It is to recognize that what we call an “image” today is often a residue, of processes, of devices, of decisions made by both artist and algorithm. And yet, paradoxically, it is in this residue that Guyton locates a strange vitality. Not a return to meaning, but a persistence of form—a form that flickers, hesitates, stutters its way into presence.

He does not give us pictures. He gives us what remains after them.

The Exhibition as Operating System

If Wade Guyton’s individual works function as files, open, unstable, subject to disruption, then his exhibitions operate as the system architecture that runs them. The gallery becomes not a neutral container but an active interface, a responsive matrix where images, formats, and temporalities are executed, crashed, and reassembled. The exhibition is no longer a stage on which objects perform; it is the software that governs their behavior.

From early solo presentations to major institutional retrospectives, Guyton has approached exhibition-making with a logic that resists theatricality and favors procedural transparency. The walls are often left unpainted. The canvases are not centered. Works lean against walls, are hung too low or too high, sometimes stacked, sometimes doubled. The gesture may seem casual, even indifferent, but it is, in fact, rigorously calibrated. Like a designer debugging an interface, Guyton tests how much the system, the space, the institution, the viewer, can tolerate before it reveals its underlying code.

Nowhere is this clearer than in his 2012 survey at the Whitney Museum, where Guyton broke with the linearity of the retrospective format. Instead of presenting a chronological sequence of works, he allowed multiple versions of similar images to coexist. Paintings with nearly identical compositions, black U-shapes, flame prints, were hung side by side, inviting a confrontation with difference that is almost imperceptible. In doing so, he foregrounded the notion of versioning, of iteration without finality. The exhibition became not a record of achievement, but a live environment in which repetition exposed variance.

This approach is not merely formal; it is ontological. Guyton does not present objects, he presents conditions. The walls become part of the work, just as the viewers’ movement, the lighting, and the institutional frame become variables within an open system. Like the operating systems that govern our digital lives, his exhibitions are full of invisible instructions. Where to stand. What to miss. How to navigate not just space, but a logic of malfunction.

There is also an implicit critique at play. By refusing spectacle, by undermining the polished neutrality of the white cube, Guyton draws attention to the mechanisms of display itself. The gallery, like the printer, becomes a device with its own politics—its own breakdowns. The stuttering inkjet is echoed by the misaligned wall text; the corrupted file finds its analogue in the incomplete checklist. These are not errors to be corrected, they are cues. And through them, Guyton invites us to reimagine the exhibition not as a conclusion, but as a provisional state: a desktop in the midst of rebooting.

What emerges from this is a form of aesthetic durationality. The works do not just sit in space, they unfold over time, across formats, between versions. Like updates released over successive operating systems, each show is both a repetition and a patch. This is why his exhibitions resist the language of mastery or closure. They remain open, elegantly, deliberately, like a file left unsaved.

Intentional Failures

There is a certain beauty in failure, particularly when it is chosen. For Wade Guyton, failure is not a malfunction to be corrected but a space to be inhabited. His works are not broken despite themselves; they are broken on purpose. And in this deliberate disobedience, they articulate a powerful resistance: against smoothness, against optimization, against the myth of seamless production that defines both late modernism and late capitalism.

The ink streaks, the misaligned margins, the ghosting of overprinted text, these are not accidents; they are engineered breakdowns. Guyton does not merely accept the printer’s flaws, he courts them. He feeds the canvas manually, disrupts the alignment, reruns the same file multiple times. He stages the conditions under which the machine ceases to behave as expected, and then treats those moments not as aberrations, but as meaning.

This embrace of error recalls, but also diverges from, the logic of chance in earlier avant-garde practices. Where Cage or Cunningham surrendered to indeterminacy as a philosophical posture, Guyton treats error as a tool within a controlled system. The failure is neither divine nor arbitrary, it is calibrated, procedural, repeatable. His practice is less about letting go, and more about knowing precisely when and where to lose control.

The significance of this cannot be overstated. In an era obsessed with precision and high resolution, Guyton’s works remind us of the friction embedded in every system. Even the most rational tools, word processors, desktop printers, standardized formats, carry within them the potential for collapse. What he reveals is that this collapse is not a flaw in the system; it is the system, exposed.

Indeed, what we often perceive as “painting” in Guyton’s work is, on closer inspection, the visible trace of things going wrong: ink pooling in unexpected areas, files becoming unreadable, hardware rebelling against its assigned task. These failures accumulate not as noise but as signal. They form a new kind of visual vocabulary, one that speaks in blurs and bands, glitches and overlaps.

But failure, for Guyton, is not only a technical phenomenon; it is also existential. It points to the limitations of the artist’s agency, the fragility of meaning, the entropy inherent in every act of creation. His works often feel unfinished, not because they lack resolution, but because they resist it. They are open, suspended, caught mid-process. They seem to ask not what is this? but how much of this was meant to happen?

That ambiguity is precisely where their strength lies. By making failure visible, intentional, and productive, Guyton redefines authorship not as mastery, but as negotiation. Not as command, but as choreography, with the machine, with the material, with the institution, with the idea of art itself.

To fail intentionally is not to quit. It is to operate in the space just before collapse, and call that space home.

The Posthumous Artist in Real Time

Wade Guyton is, in a sense, already posthumous. Not because his work has ended, it hasn’t, but because it has already been absorbed, classified, historicized with a speed that once required decades. His exhibitions are studied like case law; his canvases appear in textbooks before the ink has dried. Institutions have not only embraced him, they have canonized him in real time. The result is a strange temporal disjunction: an artist whose legacy is being constructed while he is still updating the file.

This condition is not entirely new, but in Guyton’s case, it is uniquely acute. The velocity of the contemporary art world, its hunger for relevance, its mechanisms of instant acclaim, has accelerated the timeline of reception. Critical discourse, market validation, and institutional framing now converge at a speed that outpaces artistic evolution. Guyton, operating at the center of this vortex, produces work that is both artifact and interface, both record and rehearsal. He is not outside the system; he is its most articulate symptom.

And yet, his work resists closure. Even as it enters collections and museums, it retains an aura of volatility. The canvases may be hung on pristine walls, but they still carry the trace of the printer jam, the ink error, the misalignment. Each piece is a frozen performance of something that might have failed, and perhaps did. This resistance to finality gives the work a peculiar kind of afterlife: it remains alive by staying unresolved.

There is also a deeper paradox at play. Guyton’s method, repeating files, reprinting images, versioning paintings, suggests a practice that should be endlessly scalable. And yet, he resists that logic. He does not outsource his production. He feeds the canvas into the printer himself. He insists on the slowness, the friction, the glitch. It is as though he is actively sabotaging the conditions that would make him industrial. He stages his own impossibility.

This tension, between mass reproducibility and singular failure, between legacy and liveness, is what makes his work feel simultaneously dated and prescient. Guyton gives us paintings that seem to arrive from a future already disenchanted, already archived. They do not seek novelty; they expose the structural fatigue of newness itself. In this sense, he is not only a post-digital artist, but a post-temporal one.

And perhaps this is the quiet provocation at the heart of his project: to make art that knows it will be historicized instantly, and yet refuses to behave accordingly. To let the canon form around him without solidifying. To remain in process.

To live as if already remembered, but not yet finished.

fakewhale

Founded in 2021, Fakewhale advocates the digital art market's evolution. Viewing NFT technology as a container for art, and leveraging the expansive scope of digital culture, Fakewhale strives to shape a new ecosystem in which art and technology become the starting point, rather than the final destination.

You may also like

Curator Spotlight #4: Yuqian Sun

In this new chapter of the “Curator Spotlight” series curated by Giuseppe Moscatello and

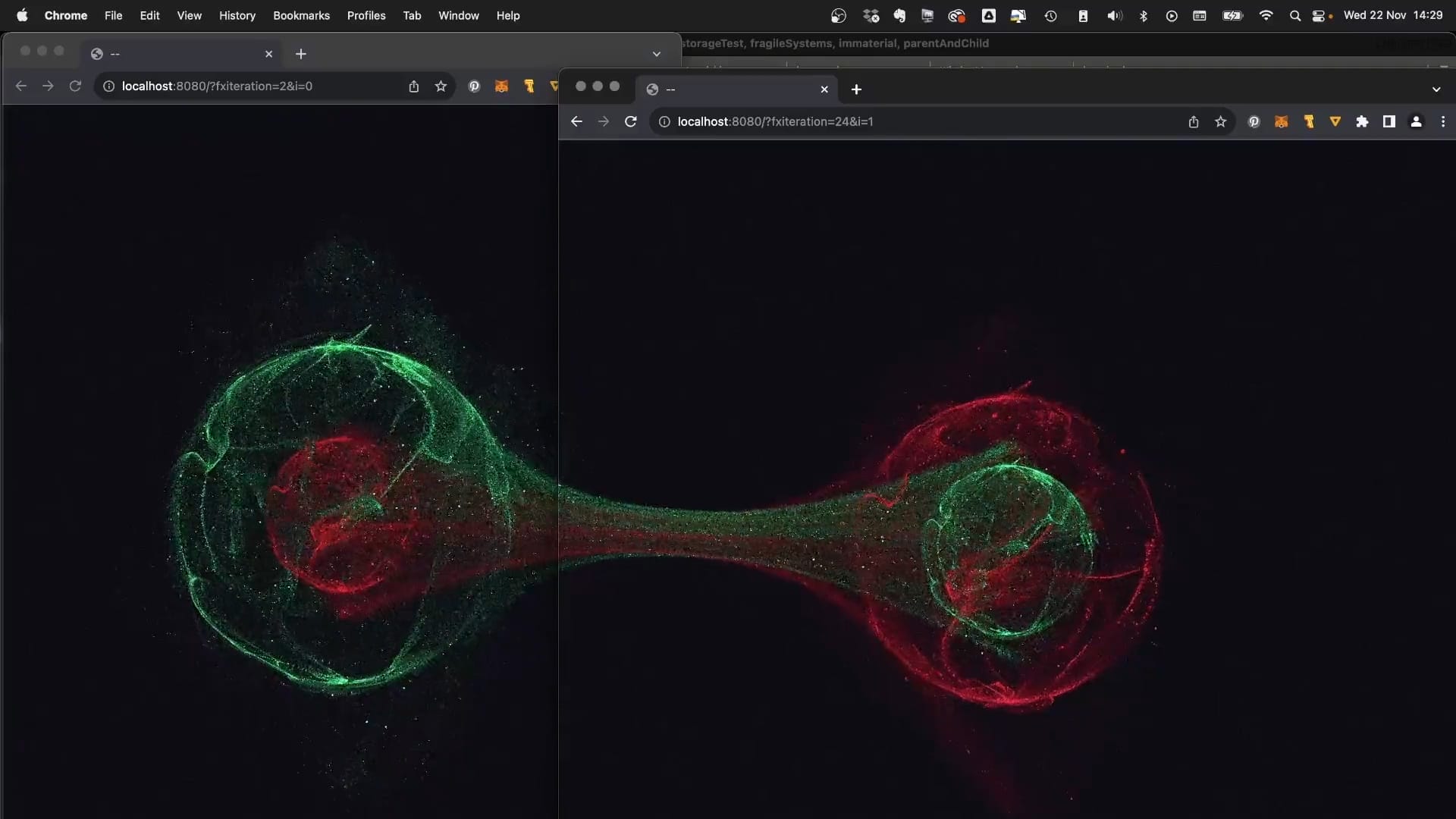

Bjørn Staal and the Art of Connecting Worlds Through the Browser

When it comes to digital art, Bjørn Staal embodies a profound understanding of the ties between art

Nina Canell “Future Mechanism Rag Plus Two Grams” at Simian, Copenhagen

As soon as you enter the exhibition space at Simian in Ørestad, Copenhagen, for Nina Canell’s