Tech That Won’t Die, No Matter How Hard Capitalism Tries

I haven’t had the chance to check out But Can It Run Doom IRL. Sadly. But in a way, I’ve been there. Before I mean. Maybe not in the physical white-walled space of Super Dakota, but in the glow of old CRT screens, in the weight of a console in my hands, in the moments where a game lingers just a li’l too long on the edge of something almost emotional, almost human. Janne Schimmel’s solo exhibition is about hardware and games, about memory, persistence, and about subverting the planned obsolescence that represent most of our digital culture. About dead tech that refuses to die. About ghosts that refuse to be exorcized. About god-like machines that are god actually.

In But Can It Run Doom, Schimmel’s artworks force us to confront the materiality of gaming. Not as an immaterial pastime, but as a form of culture tied to hardware, bodies, and social structures. Gaming is often framed as ephemeral, existing in a cycle of hype, release, and inevitable abandonment. But every game that ‘ends’ still stays in the hands of those who refuse to move on. Whether they are Twitch speedrunners and hardcore gamers pushing mechanics to their limits, or hackers cracking open engines to make them do illegal things Nintendo, Sony, and others never intended.

Nostalgia as Counter-History

And yet, Schimmel’s work takes a different approach. While most embrace nostalgia as a form of comfort, his pieces offer something much more subversive. There’s a vibe in this show, but not the retro-fetishism that capitalism loves to recycle into whatever can generate cash. We are not talking about reminiscence as regression here, but rather as counter-history—anemoia. A craving for alternative timelines, for paths not taken. Forbidden.

Mark Fisher, in Ghosts of My Life, described the “slow cancellation of the future”, the way neoliberalism has stripped us of radical visions of what technology could be. This leaves us with endless reiterations of the past. The gaming industry, much like the music and film industries, feeds on this loop. Every few years, gaming systems are replaced, franchises rebooted, and old titles remastered. But in the end, nothing really changes. The structure of gaming remains rigid. Rather than evolving into open-ended, community-driven platforms, gaming has become hyper-corporatized. Hardware is more restricted than ever, and digital rights management has fragmented the culture.

Schimmel’s work cuts against this. He keeps tech alive and relevant not as a collectible, but as a counterfactual experiment. In this context, questions rise. What if? What if gaming had taken a different route? What if open-source ideals had created it from the start? This way, his work aligns with the right-to-repair movement, the modding community, and the broader discourse against digital enclosures. It reclaims creative and technological agency from an industry that is made on built-in expiry.

The Machine as Ghost

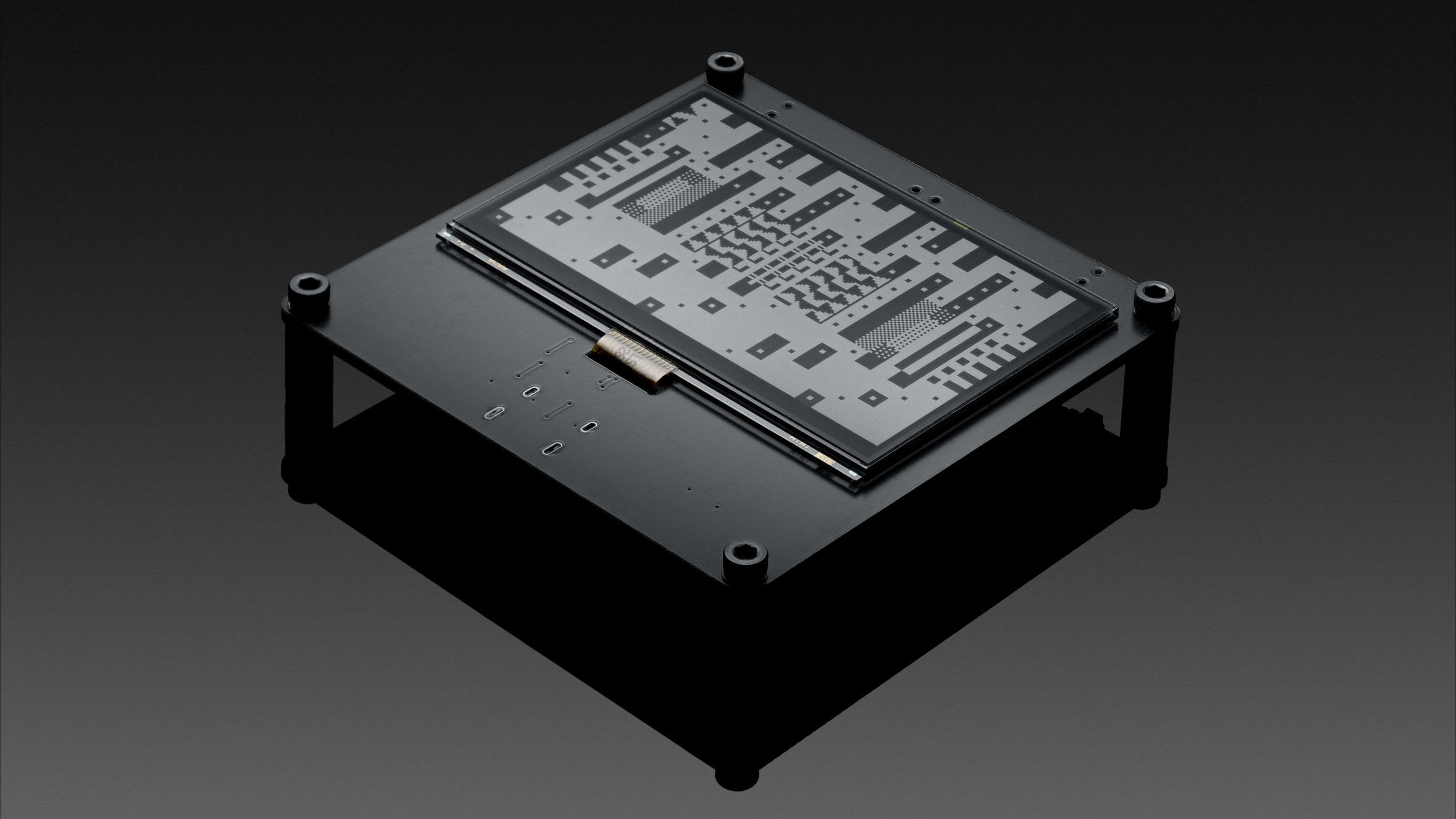

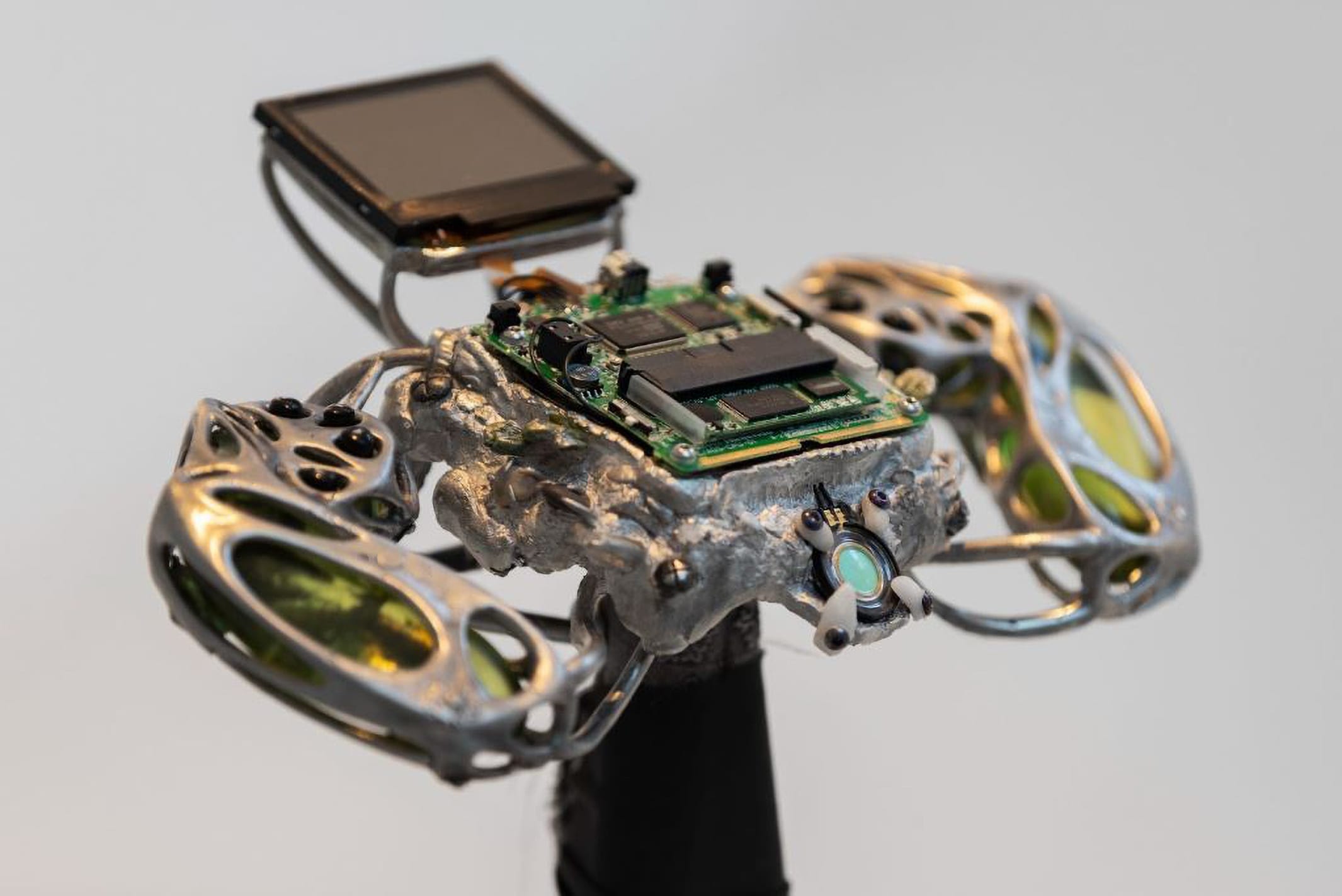

It reminds me of those machines that never quite disappear because someone, somewhere, at some point in time, keeps them running: the modders, the homebrewers, the ones getting through proprietary hardware and rewriting the rules of obsolete electronics. Schimmel works with old systems, extending the lifespan of GameBoy Advances and Nintendo DS, protecting them from slipping into the abyss of fading tech.There’s something intimate about this. Holding onto a piece of hardware long past its commercial relevance, the way a well-worn controller fits differently in your hands, the way an old screen glows just a little warmer than an LED ever could. Maybe it’s just muscle memory or something deeper. Maybe these machines, like Fisher’s hauntology, continue to whisper to us because they carry the weight of lost potential.

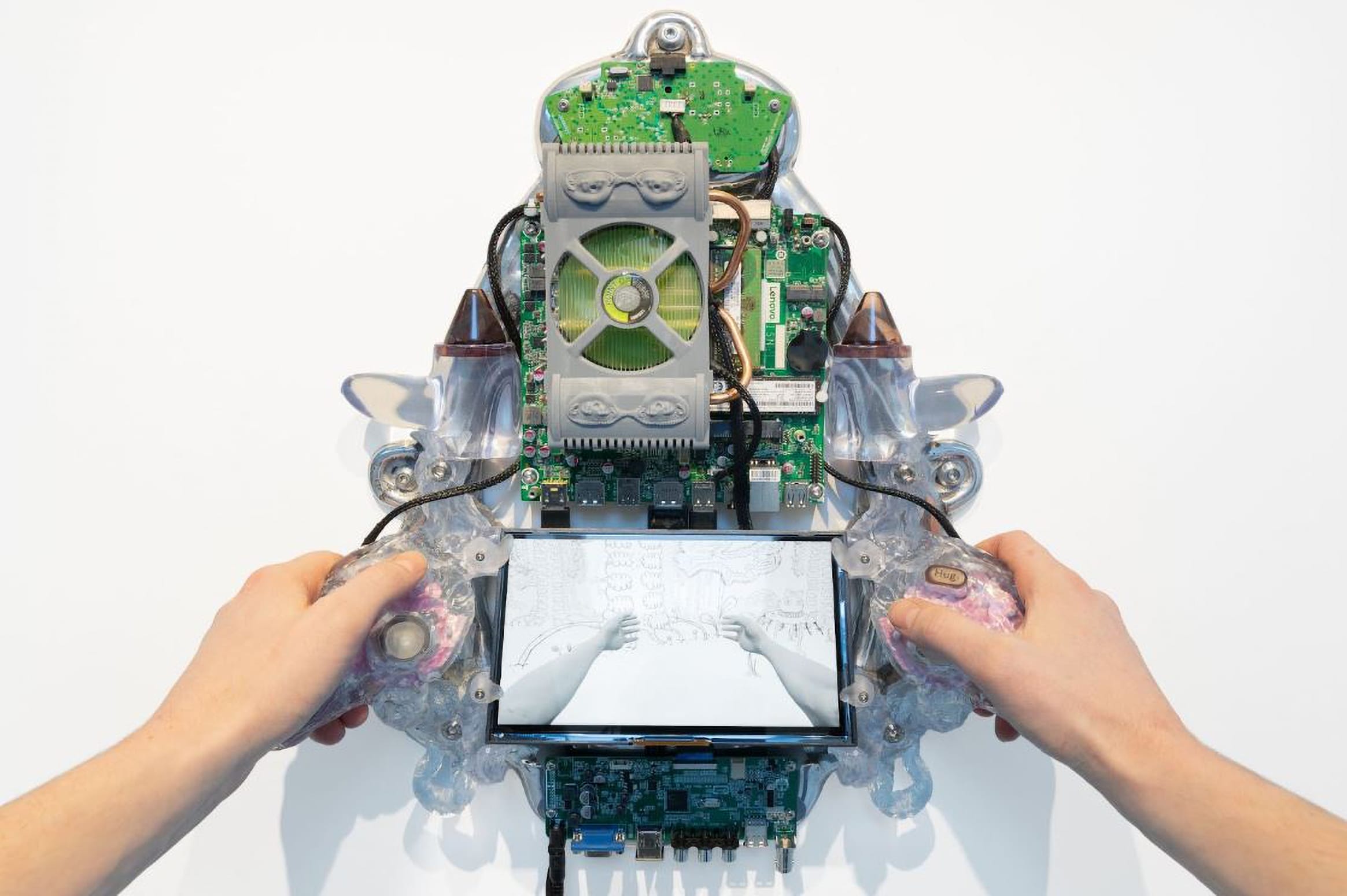

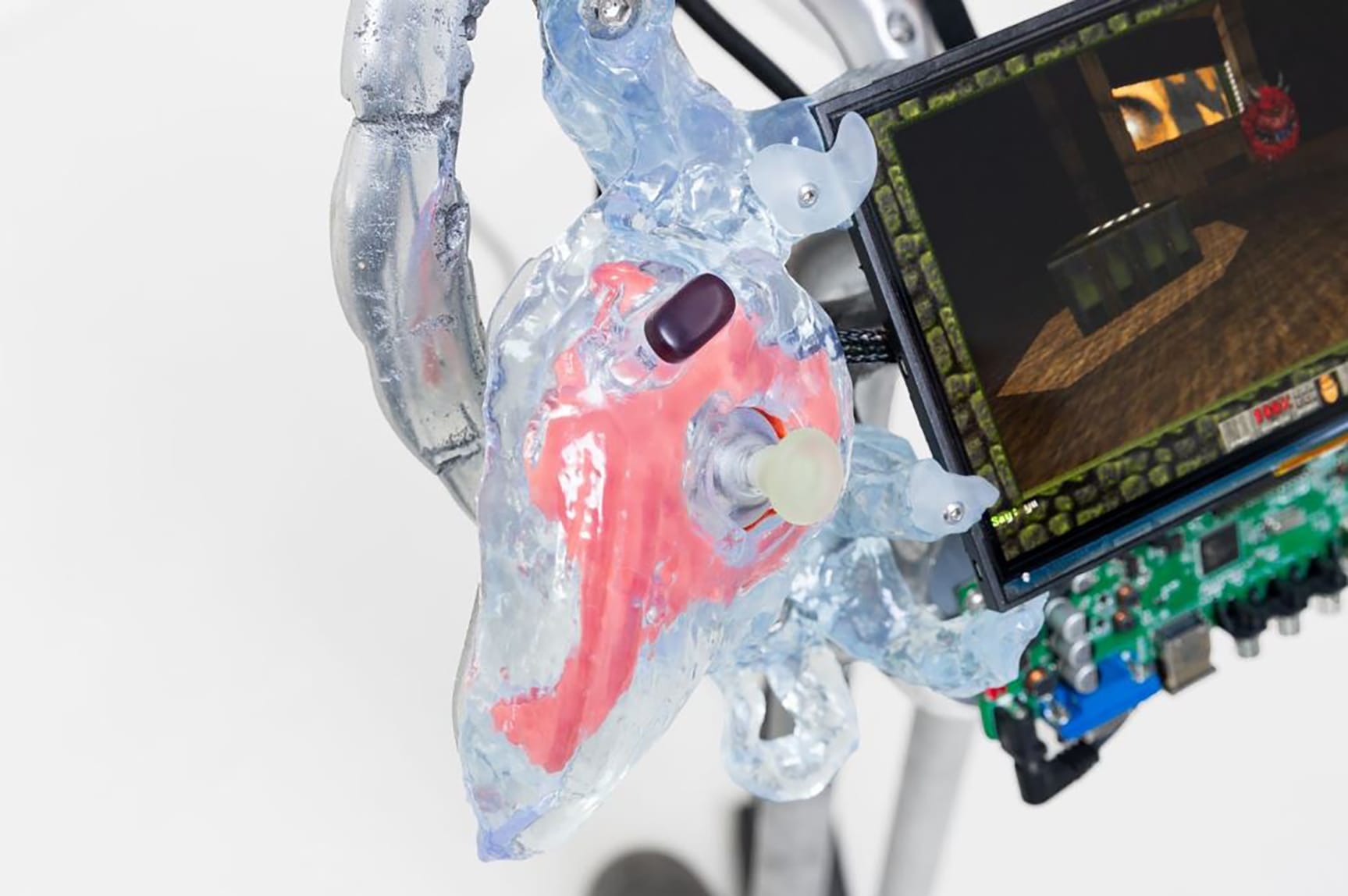

His works Doom Passive Mod and First Person Hugger rewire the logic of FPS games, rejecting violence in favor of something softer, stranger. No enemies. No weapons. Just hugging, listening, lingering. In the text accompanying this show, Schimmel recalls a childhood moment when a game seemed to offer infinite possibility but turned out to be a closed system. His mother once suggested he give a woman flowers in GTA: San Andreas, only to realize the game’s only option was to use them as a weapon. That moment reveals something; virtual worlds are simulations, but also ideological blueprints. They encode rules about power.

This tension—between what’s possible and what’s enforced—runs through the entire exhibition. Strange Loop and Projections reveal the glitches and distortions that emerge when human expression is translated into digital form. Motion capture, once designed to create perfect doubles, instead reveals the gaps. It could be related to N. Katherine Hayles’ idea that we’ve always been posthuman, stretched between flesh and data, between what the system registers and what it leaves behind. The digital body is finally never whole; it is an approximation.

But Can It Run Doom?

And then there’s Doom, always Doom. The title itself is a portal. If you’ve spent enough time in digital subcultures, you know the reference, right? Can It Run Doom? is a meme, becoming a challenge. Doom on microwaves. Doom on ATMs. Doom hacked onto a John Deere tractor as a f#%& you to corporate tech lockdowns. Doom here. Doom there.

Because that’s the deeper layer of this meme. Beyond the absurdity, it’s a form of defiance. Booting up Doom on a restricted machine is to prove that tech is not as locked down as corporations want you to believe. The John Deere example is a case in point: modern tractors are software-locked, preventing farmers from repairing their own machines. The hacker who got Doom running on made a statement about digital ownership and control. The same goes for gaming hardware. Every console generation becomes more restricted. Operating a game on unsupported devices is a way to conquer the machine.

Schimmel’s work has the same energy. His consoles suggest a broader critique of digital culture. They remind us that hardware should belong to the people who use it, not the companies that sell it. Because today tech is dominated by subscriptions, DRM, and proprietary systems, playing a game on something you shouldn’t be able to is a form of resistance.

A Future Still Out There

Sometimes I wonder what it would be like to see our tech from the outside, from the vantage point of a distant future where all of this is just archaeology. A world where our sleek, locked-down devices are incomprehensible relics, but Schimmel’s hacked consoles still flicker with something alive.

As many have argued, including N. Katherine Hayles, the human condition has always existed in a liminal space—caught between dimensions, materiality, and the unknown. But there’s another way to read that. We’ve also always been haunted by the futures we never had, by the possibilities foreclosed before they could even take root.

Maybe the world where gaming remained open-ended, where modding and hacking weren’t fringe activities but core elements of play, isn’t entirely lost.

Maybe it’s still out there, running on modded hardware, buried in obscure forums, waiting for some nerds to dig it back up.

Maybe it’s not too late to reclaim that space, where gaming is more than just a product, but an evolving expression.

b.p.

Benoit Palop

Benoit Palop is a Tokyo-based producer, writer, and curator with over 13 years of experience exploring how digital ecosystems, decentralized networks, aesthetics, and communities shape culture. He co-founded LAN Party, a curatorial and research duo focused on internet subcultures and gaming theory, and holds a Master’s degree in Research in Digital Media from Sorbonne University, Paris.

You may also like

“The Gatherers” at MoMA PS1: Where the Superfluous Stares Back

“The Gatherers”, 24 April – 6 October 2025, MoMA PS1 (Long Island City, New York, USA), cura

Andreas Gysin’s Digital-Physical Continuum

Andreas Gysin is a Swiss-born graphic designer and generative artist that stands at the intersection

On animated architecture at Soft Power, Berlin

On animated architecture by Maija Fox, Jakob Francisco, Dongchan Kim, Nina Nowak, Esteban Pérez, an