Fakewhale in Conversation with Operator

Today, few artistic collaborations stand out as distinctly as Operator, the dynamic duo of Ania Catherine and Dejha Ti. Since their inception in 2016, they’ve been at the forefront of blending immersive art with cutting-edge technology, creating experiences that challenge traditional perceptions of the digital and physical realms.

Ania Catherine’s foundation in choreography and performance art, combined with Dejha Ti’s expertise in multimedia art and human-computer interaction, has enabled Operator to craft installations that are both thought-provoking and emotionally resonant. Their work delves deep into themes of privacy, surveillance, and the intricate dynamics of human relationships in the digital era.

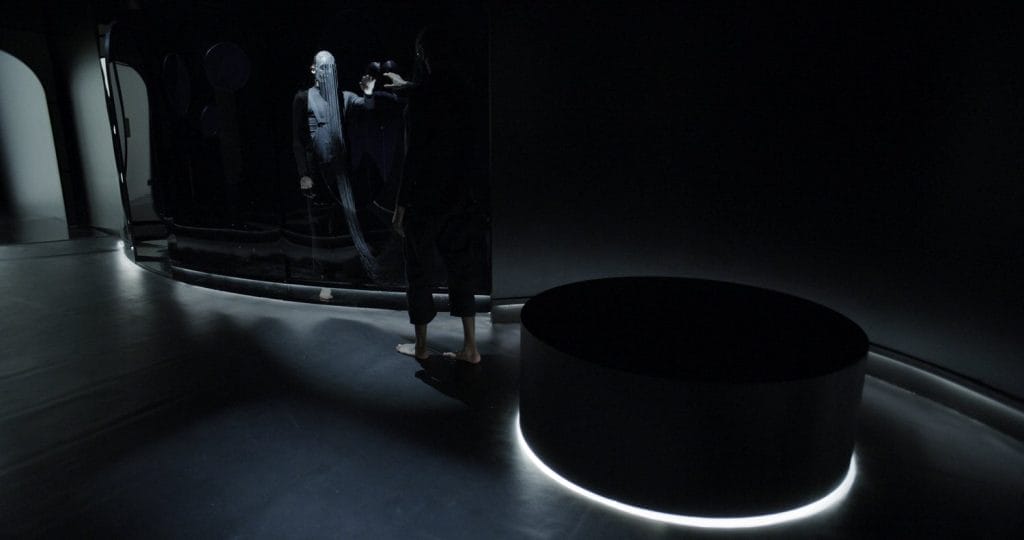

Notable projects include “On View,” commissioned by the SCAD Museum of Art in 2019, which critically examines the commodification of identity in our surveillance-driven society, and “Human Unreadable,” a groundbreaking project that introduces an on-chain generative choreography method, seamlessly integrating human movement with algorithmic processes to explore the symbiotic relationship between the body and code.

Operator’s innovative approach has garnered significant recognition, including the prestigious Lumen Prize and features at esteemed platforms such as Christie’s Art+Tech Summit and Ars Electronica.

In this exclusive interview, Ania Catherine and Dejha Ti shed light on their collaborative journey, the fusion of technology and human emotion in their art, and their vision for the future of digital experiences.

Operator: Rethinking Digital Art and the Body

Fakewhale: Your artistic collaboration began in 2016, merging your distinct backgrounds in choreography and multimedia art. How did your initial projects shape the trajectory of Operator, and what were the pivotal moments that solidified your partnership?

Operator: Our first artwork was a film called Line Scanner, which merged live-triggered, projected animations onto improvised movement. Ania was dancing on the floor and Dejha had a projector rigged to the ceiling and was projecting line animations onto her. After we got the projection and dance combination “out of the way” – we say that because it was kind of the most obvious way we could have merged both our practices at that point, then we moved into performance installations where we were more conceptually worldbuilding projects that were experienced live by an audience. It is important to note that at this point we had no relationship to the art market, and were both supporting ourselves in ways that were kind of adjacent to, but not actually through artmaking. Dejha had a design studio and was doing freelance experiential design, creative/technical direction for corporate clients and Ania teaching dance and choreographing for film & music videos. Most of our early works during the first two years of our artistic practice were these rare chances when we were asked to make something, often by a friend, which meant that most of our early works were music videos. These were the one-off instances when we would be given a small budget to experiment creatively together. Even Line Scanner was actually created on the tiny break between a project we were doing for a client (visuals for a corporate event). We skipped lunch in order to take advantage of the setup and make something. Our first properly resourced performance installation was a commission by Adidas in 2018, the resulting work was called off is on. Based on how we felt making that work, as well as the response, we knew that we wanted to bring our practice to the next level and not just be squeezing in collaborations on the side when we could, but actively find ways to realize more projects that were the fullest manifestation of our combined visions. Curator Storm Janse van Rensburg happened to see off is on on social media, we had a couple meetings, and the following month he commissioned us to create a new experiential work at the SCAD Museum of Art. That was a pivotal moment. I’d say our early days, trying to make magic and produce grand projects on shoestring budgets, each of us wearing a hundred hats, were formative. At the same time, working on corporate projects taught us the ins and outs of production and how to execute at a high level. That combination was solid training, and we’re still benefiting from it today. Because of these past experiences, we see the millions of micro decisions that go into the making of an artwork that some might write off as merely “production details,” as actually essential to the way the work becomes its fullest self and the difference between good and ‘wow.’ Production and execution are paramount. This in a way goes against the premise of conceptual art, where the thing itself is less important than the idea. Our work is conceptual, but also we value polished execution immensely. We also love paradoxes though so this is I suppose conceptually sound.

Fakewhale: Your work often brings the physicality of performance into digital spaces. How do you approach the translation of bodily experiences into virtual realms, while preserving the essence of human movement?

Operator: We often show the body in our work to remind ourselves and others that while we are accelerating or augmenting our lives with technology, we still look with eyes and type with fingers, need sleep, sunlight, touch, to retain a sense of being physical beings. But technically it is not always easy. For example for Human Unreadable in order to be able to retain the essence of the movements from the movement library while not spending obscene amounts of money on storage, we needed to go through each movement and choose only the necessary bones of the body to be uploaded for each move to not spend extra money uploading unnecessary data. The process was complex and painful but it was necessary to retain the essence of the body in the final output. Without this immense and unseen backend work, the impact of the work would not have been the same.

Fakewhale: In “Human Unreadable,” you developed an on-chain generative choreography method. Could you elaborate on the technical and creative processes behind this integration, and how it has influenced your subsequent works?

Operator: We knew we wanted to explore the medium of long form on-chain generative art but wanted to put the body at the center. That early thought led us to create a collection that is in alignment with the conceptual framework of the larger Privacy Collection–focused on the tension between privacy and transparency inherent in blockchain technology–but also builds on and combines multiple historical strands, including:

1) the embodied approaches to digital art pioneered by artists like Rebecca Allen, Analivia Cordeiro, Jeanne Beaman

2) the E.A.T. Movement (Experiments in Art and Technology)

3) Cunningham’s Chance Dance Method

There were many barriers to overcome in order to integrate the body so deeply into an Art Blocks release, as the platform was not designed to produce performance. In the process of making Human Unreadable, we created several tools in order to realize the work, which we are making open source and in the end became the Operator Generative Choreography Method. Upon minting, the algorithm didn’t just create an image, but it actually created a unique dance sequence, and the motion data drives the p5js parameters that become the final image, and each sequence is stored on-chain, making movement collectable as an art object. We are passionate about leveraging technology to introduce new ways for artists who work in ephemeral mediums to have new ways to sell their work (and in turn support their practices), particularly in light of cultural funding being cut, dancers and other performing artists historically not having a way to participate in the art market. Making movement collectable as a scarce digital asset is hopefully a first step towards creating a new audience of collectors and patrons of dance and performance, giving artists new ways to monetize their work, take bigger risks, and allow the field to continue evolving.

Human Unreadable (2023) by Operator | Overview video

Fakewhale: Last September, The Paris Opera’s “Coddess Variations” utilized your Generative Choreography Method. How did this partnership come about, and what were the unique challenges and insights gained from integrating your algorithmic approach into a classical institution’s project?

Operator: Hermine Bourdin, the artist behind Coddess Variations had an ongoing collaboration with Paris Opera dancer Eugenie Drion, doing really interesting work bringing her sculptures to life digitally through dance and motion capture. The next phase was going to be in collaboration with the Paris Opera, working closely with their costume department to create a wearable sculpture that Eugenie would perform live in. Hermine was looking for a choreographer, so Ania joined the team to choreograph the performance. As Hermine already had a history of merging sculpture, dance and technology, we thought it would be the perfect opportunity to bring the Operator Generative Choreography Method to the creation and collecting process of this unique performance. Our open-source method was used to generate the dance sequence–the solo is composed of 9 chapters representing three manifestations of the goddess (maiden, mother, and crone) and our algorithm determined the order of these 9 chapters, and also allowed collectors to collect a visual artwork that corresponds to the motion data of a segment of the dance solo. One key difference between the use of our method in this work and in Human Unreadable was that in Human Unreadable each collector owns a unique sequence. In Coddess Variations, each collector owns a certain part of the same performance, which is a beautiful variation of how the method could be used by other artists and fit their own project and needs. To allow for this to work, Dejha and Isaac Patka, our main engineer collaborator for Human Unreadable, had to make several complex adjustments to the method, on top of changing the specific performance parameters to fit Hermine’s concept and story. We all learned a lot about the method, its flexibility, how it could be improved; it was a very enriching collaboration seeing how our tools were able to support another artist’s vision. On a personal note, going to work, walking down the hallways of Opera Garnier, rehearsing in the Foyer de la Danse, was such a pinch me moment and truly magnificent considering these spaces are so symbolic and culturally loaded for the history of dance.

Fakewhale: Earning Lumen Prizes in both the Immersive Environments and Generative Art categories is a remarkable achievement. How have these accolades impacted your practice, and what significance do they hold for you in the context of the digital art landscape?

Operator: Prizes are beneficial as means but they should certainly not be seen as an end nor are they a necessary marker for art that deserves to be seen and appreciated. We are thankful for the prizes we’ve won, which were particularly important when we were just starting out, worked with unsellable mediums, and relied solely on partnerships and commissions. Recognition can unlock opportunities, partnerships, speaking engagements, etc. Also, people outside the digital art sphere often struggle to evaluate art made with technology. In this context, digital art prizes can serve as helpful signposts, offering some degree of curation, and aiding in the sifting process.

Fakewhale: Beyond traditional art forms, are there any unconventional sources, such as personal experiences, scientific phenomena, or cultural rituals, that have profoundly influenced your creative process? How do these elements manifest in your work?

Operator: Volcanos, bathing, cats, slow cinema, Marc Weiser’s concept of ubiquitous computing.

It is unlikely you could point to how any of these have shown up directly in our work but together they form the stew from which each of our artworks emerges.

– The raw energy of a volcano that spends most its time dormant, burning quietly, a portal that connects the surface we live on with the earth’s core, defined by its quiet power and a perfect example of creation/destruction as two sides of the same coin.

– Bathing for the feeling of immersion, having the body wrapped and transformed by being held, how it impacts one’s interior, one’s movement in a profound but simple way. It is total immersion without relying on scale.

– Cats for style and just being holy beings that we aspire to be like every day.

– Slow cinema for its rejection of giving into a society of constant distraction and shortening attention spans, a circular understanding of time, the importance of patience with art, honoring time, boredom, nothingness.

– Ubiquitous computing whispers to us, like a ghost in the machine, shaping how we think about presence, absence, and the quiet choreography between humans and invisible systems.

Fakewhale: Looking ahead, are there specific technologies or societal issues you are eager to explore in your upcoming projects? Any upcoming projects to keep an eye out for?

Operator: We are currently working on Human Unreadable Act III, the final performance and culmination of the 4-year endeavor, which will be a gesamtkunstwerk and is keeping us 1000% busy for the moment. The performance will take place at the end of 2026 and be hosted in a major cultural institution in the U.S. We are also in conversations with a few universities about integrating our generative choreography method into their performing arts/dance and technology curricula which is very exciting. We love the idea of students being exposed to what we have done, building on it and taking it to places we never would have imagined. We have become increasingly drawn towards finding solutions for how art is made, contextualized, sold, and how it meets the world, as we are oftentimes feeling that the existing art/culture infrastructure feels a bit stale and not in touch with the times. The conditions art needs in order to exist and circulate are subjects we are actively thinking about–performance and beyond. Privacy remains a rich topic of exploration for us.

fakewhale

Founded in 2021, Fakewhale advocates the digital art market's evolution. Viewing NFT technology as a container for art, and leveraging the expansive scope of digital culture, Fakewhale strives to shape a new ecosystem in which art and technology become the starting point, rather than the final destination.

You may also like

Liturgies of Black: Thierry De Cordier and the Discipline of Absence

The Discipline of Nothingness There are exhibitions that present artworks, and there are those that

Cryptoart, History & Perspective

Perspective matters. A lot. On the internet though, there is zero native perspective. Perspective he

Paolo Canevari: Memory, Power, and Transformation

Paolo Canevari, born in Rome in 1963, has established himself as a distinctive figure in the contemp