Manor Grunewald in conversation with Fakewhale

Fakewhale: How do you define the boundary between what is “real” and representation in art, navigating between analog and digital in your work?

I think this is a vague territory to think about; the boundaries are not so clear to me either. There is a certain circle I am working in that juggles those aspects, so I do not see too many boundaries—actually, more overlapping things. Analog, as a slow medium, contrasts with digital as a fast lane to information and processing. Digital vs. Analog could also be seen as ‘brothers from different mothers’.

Fakewhale: Could you describe how you select your initial image templates and what criteria guide your choice of details to explore and transform?

The initial image templates that I work with depend strongly on the series I am working on. Of course, there are similarities between series and the image content I collect. For example, the ‘Letratone’ & ‘Mecanorma’ series I have made came from two layers of images. One layer contains black & white photocopy studies from extremely close-ups and defaults from empty photocopies I generated through trial and error. I made those by only opening the machine during the copy process and letting light enter the glass plate, along with small defaults from the machine itself. The second layer contained a ‘Letratone’ or ‘Mecanorma’ translucent film that has a grid and its own color.

Another series called ‘Rennie’ came from an old-school Flemish cookbook ‘Ons Kookboek’. I made close-up studies of the images of the dishes in black and white. These remind me of structures like marble, stone, or other organic formations. The title ‘Rennie’ came from a stomach acid medicine. The title idea came up as the image dissolves from its original context and has a direct link to the cookbook as well.

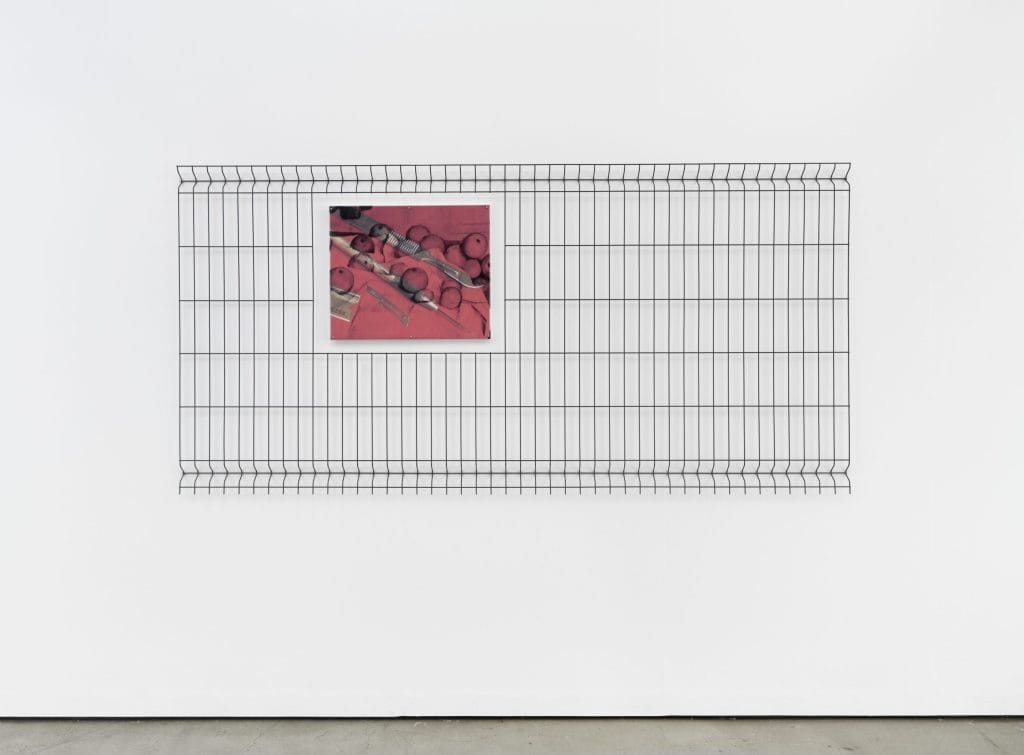

‘Re-Painting Class’ is a series I am currently working on and has a lot to do with the position as a painter and an idea of studio voyeurism. I select images from a wide range of hobby books on arts and crafts that show close-up handlings. These images represent a fictive insight within my studio practice.

Fakewhale: How does manual intervention contribute to the uniqueness and texture of your works, and how does this relate to the use of older technologies like copiers?

There is a clear link between manual interventions into the work, like classical painting with oil paints and acrylics with brushes, and the copiers. I collect second-hand copiers that companies dispose of because they are more or less at the end of their life. This gives the machines their own patina on the duplicated and printed images—traces of mechanical wheels, ink feeders that are leaking, distortion issues, and other surprises that appear. The machines add an artistic value to the duplicated images. I see this similarly to my interventions in the studio with paint and intuitive decisions that are made during the process of working on multiple works at one time.

Fakewhale: How do the texture and surface of various materials integrate into your artistic work, influencing the perception of the printed image?

Playing with different materials can create an angle to read the work on another level. A print on a flat surface, such as paper, is more commonly read visually. I strive to develop a strong visual language that starts from those plain, flat reproductions. Choosing surfaces like commercial materials such as synthetic canvas, mesh fabrics, and cloth printing, in contrast to artistically related materials like linen canvas and cotton, enriches the texture. On the other hand, texture is created by incorporating oil paint, acrylics, varnish, and spray paint within the process of the work

Fakewhale: How do you manage the balance between controlled composition and the element of chance in your technical process?

Generally, I aim to achieve a certain level in my work that balances between the residue of former images or the idea of images that are still under construction. Most of the time, I start with collected source material from a wide range of books in the studio. These images are very clear to read visually. It is my role to transform them within my visual language by playing with them through copying, editing, scaling, scanning, and printing on canvas, among other techniques. There is a lot of chance involved in this process, which creates a curiosity towards my own handling of those pictures.

Fakewhale: Could you discuss how the collaboration with Theo De Meyer for the “Goods Between Floors” exhibition has influenced your perception and use of the exhibition space?

Theo De Meyer is a close friend of mine. He’s an architect and was formerly an assistant to Jan De Vylder at ETH Zurich. He has a keen interest in scenography interventions in close dialogue with contemporary artists. We’ve talked for a long time about collaborating on a project, but we never found the right context that would satisfy both of us. The project “Goods Between Floors” emerged at a perfect time, presenting an interesting space and opportunity for us to work on the exhibition together. I have worked with Berthold Pott (gallery) for seven years, and he was very enthusiastic about the idea of hosting the show at the gallery.

The exhibition was held in the former gallery space at An Der Schanz in Cologne, an old electricity facility from the 1970s with a wide-open exhibition space on the first floor and a storage space on the ground floor, semi-visually connected to each other—hence the title of the show “Goods Between Floors.”

The visual dialogue that was created led to a good back-and-forth progression with an interesting outcome in the end for both of us. It was fascinating to see how two-dimensional paintings, books, and documentation were integrated into a total installation within the space. Despite the abundance of works on display, the exhibition still felt like a very minimal visual intervention. Theo’s choice to work exclusively with metal tubes and translucent material was key to everything.

My reflections on this experience have led me to consider more complex total installations in the future. The ideal setting for such an endeavor would be an institutional show with different spaces and series of work in dialogue with Theo. This could be documented in a book that would serve as an essential part of the exhibition, rather than merely a simple catalogue.

Fakewhale: How do you see this exploration of historical printing techniques influencing your future work with your most recent series “External Hard Disk (E.H.D)”?

“External Hard Disk (E.H.D)” has become an essential part of documenting the work, even becoming part of the title of each piece. It reflects on various aspects of an archive: collected source material, processed images, digital files, artworks, storage, and so on.

Historical printing techniques hold their own fascination. Many of these historical inventions enabled the duplication of images in large quantities to reach a broader audience. Techniques such as etching, lithography, and woodblock printing have all played their part. Of course, everything changed with Johannes Gutenberg’s invention of the letterpress in 1455, allowing books with images and contextual texts to become more widely available worldwide. Other significant movements, like silkscreen and, later on, digital printing, created new possibilities from an economic and commercial point of view.

Within the art world, artists like Andy Warhol and Robert Rauschenberg have clearly represented the concept of mass image pollution and a response to commercial PR strategies. For my own practice, it’s intriguing to consider how using original images in certain techniques can contribute. I enjoy playing with all these methods, exploring how I can blur the boundaries between techniques and their contexts.

Fakewhale: Could you talk about how the final interventions with spray, acrylic, and oil integrate or transform the image you have developed?

For all the works, the process from ‘A to Z’ is crucial in developing an end result that resonates with deeper intellectual layering for both the audience and myself. By incorporating materials such as acrylic and oil paint, which are directly associated with the romantic notion of a painter, I can meet certain expectations of what a painting should represent in classical terms. This approach also serves as a method to engage the viewer with the various layers of the work, revealing itself more fully upon closer inspection. The traces of the source material, the process of copying, printing, stretching, and painting, all contribute to the overall experience of the work, playing their respective roles in its creation and interpretation.

Fakewhale: How do you see the relationship between the different aspects of your work, from the two-dimensionality of the canvas to the three-dimensional space with installations and sculptures?

Ideas can emerge based on the conditions of the exhibition setting and the series I am working on at that moment. Some shows call for a classical hanging of two-dimensional work, while others offer the opportunity to foster a deeper dialogue between the architecture of the space and the work itself. Effective scenography can enhance both. Most of the time, the sculptures or installations I create are a response to the space. Deeper conceptual ideas around archiving, processing, and duplication are often present within more complex installations, reflecting a thoughtful engagement with the themes and the physical environment.

Fakewhale: What new techniques or media are you interested in exploring, and how do you foresee your creative process and works evolving in the coming years?

It’s an intriguing point, as the array of techniques available to artists is indeed vast and seemingly limitless. The challenge lies not in getting lost within this extensive array of options but in continuously discerning what might be beneficial or not. It’s relatively easier to determine what to exclude from your practice, yet more challenging to confidently choose what to use in a specific series of work without going overboard.

Currently, I’m interested in exploring more with a vertical UV printing machine, as this technology opens up new possibilities that weren’t feasible just a few years ago. The vertical printing offers a larger scale to work on compared to UV flatbed printers, and its experimental potential seems more intriguing since this machine could be easily integrated into the studio. Moreover, printing vertically on paintings feels more natural than doing so flat.

For the coming years, I aim to focus more on finding the balance between classical painting and printing, and to incorporate these into autonomous sculptures as a next step. This exploration seems like a natural progression in pushing the boundaries of my work while staying true to its core principles.

fakewhale

Founded in 2021, Fakewhale advocates the digital art market's evolution. Viewing NFT technology as a container for art, and leveraging the expansive scope of digital culture, Fakewhale strives to shape a new ecosystem in which art and technology become the starting point, rather than the final destination.

You may also like

“Resonance” at Kunstraum Steiermark, Vienna

Escape. Resonance by Lena Baloch, Michael Fanta, Susanna Hofer, Lisa Reiter, Nina Schuiki, Katharina

Private on Display: Juliette Blightman and the Performance of Intimacy

“Art is the only serious thing in the world. And the artist is the only one who is never serio

Mark Webster: Evolving Aesthetics through Code

Born in Canada and raised in the UK, Mark Webster is a key figure within the visual and sonic arts r