Fakewhale in Dialogue with Oliver Hull

Oliver Hull is an artist who skillfully blends art, technology, and critical reflection on complex themes such as randomness, image perception, and the effect of digital tools on reality. Through conceptually dense installations, Hull explores the relationship between the natural and virtual worlds, creating works that invite the viewer to reflect on the complexity and unpredictability of existence. His ability to transform scientific data and advanced technologies into rich and thoughtful visual experiences makes him a prominent figure in contemporary art.

We had the pleasure of speaking with Oliver Hull to delve into the creative processes behind his works, the challenges he faces in combining art and technology, and his visions for the future. Below is a series of questions that explore various aspects of his artistic practice, from the techniques used to the concepts explored, to collaborations and influences that have shaped his journey.

Fakewhale: In your artistic practice, what recurring themes do you explore, and how have they evolved over time?

Oliver Hull: My work has historically dealt with specific sites or events which could be understood as hybrid, in that understandings of them were formed remotely through representations before being physically experienced or lived in. Understandings of them often mix with myths or fictions alongside scientific study so they become a kind of hybrid of material/image/scientific research/myth. Some of these places were Outer-Space or Mars or The Marianas Trench. The works tried to amplify these relationships, increasing their dissonance.

I still make some works, but more often works embody a murkier media/environment. I tend to focus more on technologies and systems that embody these ideas, trying to make work which intervenes in the system itself.

work which intervenes in the system itself.

Your works often involve complex simulations and advanced technologies. What role does technology play in your artistic practice, and how do you see its future development in your works?

I’ve always been interested in technology. As a young kid, my first interactions with digital technology were through the family computer, which sat in the corner of my parents’ living room. It was a completely mysterious object to me. I had no idea how it worked; I mainly used it to play The Sims. One night we had a huge thunderstorm and lightning struck our house, shorting the computer. I remember being super annoyed that my Sims were dead, but on reflection, it was amazing they were in a way physically still there in the room with us, being affected by the same weather as us, being killed by lightning.

During my studies under Paul Thomas is really when I started thinking about how we use technology to define the world more seriously. I was working on a project about fiction at the time and I remember Paul telling me he didn’t understand why people were interested in fiction/fantasy or virtual reality when the world is so much more weird and complex. I took this to mean the closer we look at anything, the more complex and strange it is. The world has infinite resolution. Technology and science are just one way we try to interface and understand complexity. This started me thinking a lot about how we use technology to monitor, sense, and measure, to extend our senses and ultimately define the world.

When I make a work using technology as the starting point, the initial ideas usually begin through some emotional or intellectual problems related to the specific tech. I think there’s a large conflict, a knot, within technology that is hard to untangle – these works are like me trying to see specific aspects of it. My approach to making with technology is usually about taking pre-existing technologies—essentially readymades—and combining them with custom code to try to interrogate that specific thing I’m interested in, and what it’s entangled with. To allow that software and the systems it’s in to reveal their bias about the world, and for me to watch them unfold.

These works, such as Surface (2017) or Random Cube (2023) or Random Cube (Guy’s PC) (2024), were made to be live and dynamic so they change with the world. As they run, I’m often surprised by what they do or how they fall outside of what I’ve initially set out to do.

I’m not sure about the future. Current developments make technology feel wild and unpredictable again. I am worried and hopeful. It is always at the back of my mind that the history of digital technology isn’t emancipatory. Historically, most tech is developed by dominant classes and is used to further inequality or violently oppress the disadvantaged. We currently see this contemporary policing in companies like Palantir and Clearview AI and with the various technologies used in the occupation of Gaza.

I don’t think this means machine learning itself is essentially unethical or evil and can’t be used to solve big issues or help artists make new and amazing things, but it’s important to be critical of its use, its biases, and who holds the reins. I feel it is likely as we see it progress, it’s going to be more and more similar to how the early internet was replaced with various siloed platforms, mainly run by huge corporations. Now is probably the time we will see the most interesting things done with AI in an art context as there’s space for artists to develop their own AI tools, and I hope in the future this will still be possible as they become more sophisticated.

How do you approach research and experimentation in your works? Can you describe an example where experimentation led to an unexpected or significant result?

My research technique is pretty non-linear. I’m not an expert in most of the things I like to make work about, so I research intuitively, like an enthusiast. I’m not a very linear thinker, so I follow what my interests are. I usually find something in the world I find really interesting or dissonant—that seems to be hard to pin down. Then I research it as much as I can and try to make something which amplifies what I think is funny/weird/interesting/sad about it. This is usually a process of combining different interests to draw out different aspects of each.

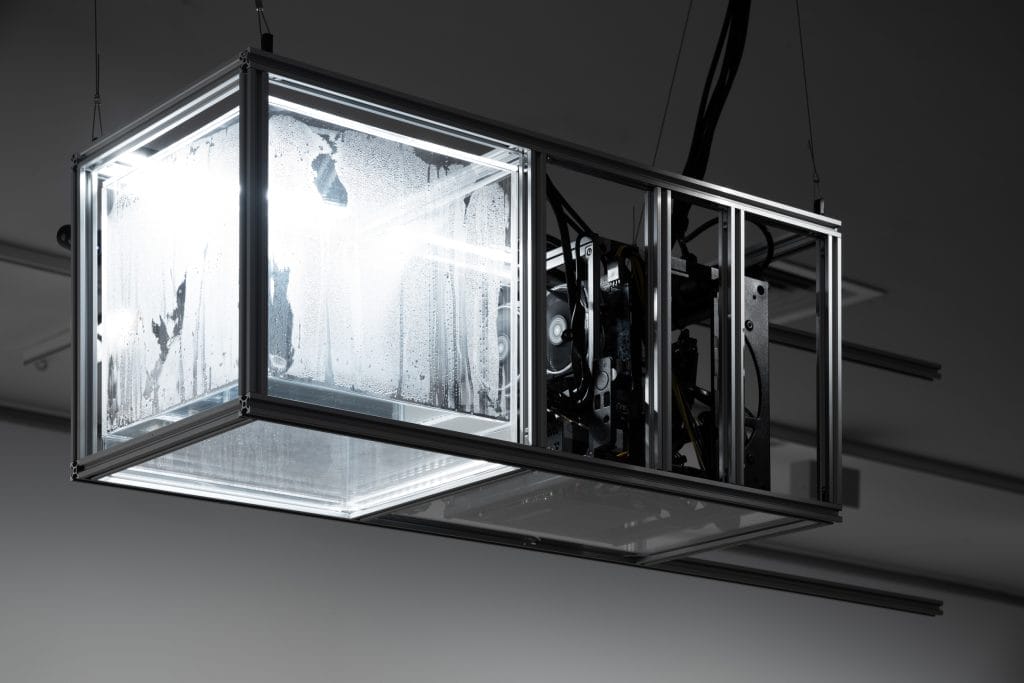

Random Cube is a good example, initially inspired by LAVArand by Cloudflare. LAVArand is a system that enhances cryptographic security by generating true random numbers using lava lamps as an entropy source. In the lobby of Cloudflare’s San Francisco office, a wall of around 100 lava lamps is constantly being recorded by a camera. The unpredictable movement and flow of the lava within these lamps create an unpredictable source of randomness.

The camera captures images of the lava lamps at regular intervals, and these images are converted into a stream of random numerical values. This randomness is essential for generating secure encryption keys, as predictable keys can be easily compromised. The captured images, with their high entropy, are used as cryptographic seeds for Cloudflare’s cryptographically secure pseudorandom number generators.

I took the idea of true randomness, one which cannot be predicted by software, and swapped out the lava lamps with Condensation Cube by Hans Haacke. Condensation Cube is one of the first cybernetic works, designed to constantly change in response to its environment like a living organism. It is an open system that continuously evolves based on its interaction with the surroundings. As Haacke said, “The conditions are comparable to a living organism which reacts in a flexible manner to its surroundings. The image of condensation cannot be precisely predicted. It is changing freely, bound only by statistical limits.” (New York, October 1965.)

The condensation which forms is the entropy source which makes the random numbers like in LAVArand, except in this case it isn’t used for security, but is the input for custom malware which controls the computer monitoring the cube itself. I worked with my good friend Alex Tate to develop the code for this, linking the random number generation to control the mouse movement, clicking, key presses, and scrolling with pure randomness. Watching the screen of Random Cube (2023) feels like a ghost or someone is remote-controlling the PC, but it’s just pure random chance. Often people assume it is AI but there is no logic, only chaos.

The idea that true randomness is somehow a reflection of the environment of the cube, that the audience’s presence, but also the extended environment—its heat, light, and humidity, which by extension is a reflection of human influence through climate change—is really beautiful to me in a very sad way. To imagine this historical lineage of what causes the mouse to click on the next ski bidi toilet link or to the terms and conditions of Temu. I didn’t intend this, to me it becomes a really emotional work, about freedom and lack and environmental destruction.

Endless Oceaning-Image” explores the concept of surface as a point of contact and separation between physical reality and visual representation. How does this work reflect your interpretation of images as simulacra, and how does it connect to your interest in visual and tactile perception?

Endless Oceaning-Image started as an experiment in giving agency to an area of the ocean—the surface above the Marianas Trench. This work was initially commissioned by Black Shuck, a digital development cooperative.

I worked with them to use a generic ocean asset and time-of-day and weather simulator within Unity and connect this to a real-time weather API sending data from the Marianas Trench region. The weather controls the simulation so it mirrors the weather in the real world. The weather also controls the camera’s panning, zoom, focus, editing, and the soundtrack. This was done to create something which uses a highly generic asset but is also highly specific in that it’s controlled by the data from that place and edited to feel filmic by the same data. In a sense, creating a film that changes and moves at the pace of the weather itself.

I realized through the making of the project that it wasn’t just about the real-world location’s weather and the simulation, but also the dispersed chain of technologies, systems, environments, and people that span the globe through which the information flows.

Collaboration is an important part of your creative process. How do you manage these collaborations to maintain coherence in your artistic vision?

Collaboration for me isn’t about coherence; it’s more about conversation and play, pushing ideas to unexpected places. My favorite thing in art is being surprised. The process of collaboration, when it works, is just constantly being surprised by what someone else comes up with or how they approach a topic/problem.

(Video link for An Event with Kieron Broadhurst and Giles Bunch: https://vimeo.com/183596770)

Often works when I collaborate are about collective storytelling or worldbuilding, such as An Event (2015-ongoing), a collaboration with Kieron Broadhurst and Giles Bunch, or Rockpools (2023) with Jess Day, Pascale Giorgi, Kieron Broadhurst, Jessee Lee Johns, Jack Wansborough. Both of these shows were experiments in developing open-ended narratives, where artists made things together and individually, but presented them together as one work.

fakewhale

Founded in 2021, Fakewhale advocates the digital art market's evolution. Viewing NFT technology as a container for art, and leveraging the expansive scope of digital culture, Fakewhale strives to shape a new ecosystem in which art and technology become the starting point, rather than the final destination.

You may also like

Leander Herzog, Heatsink, WUF, Solo Press Showcase, Basel

“Heatsink” by Leander Herzog, solo press showcase curated by Fakewhale, at WUF Basel, Ba

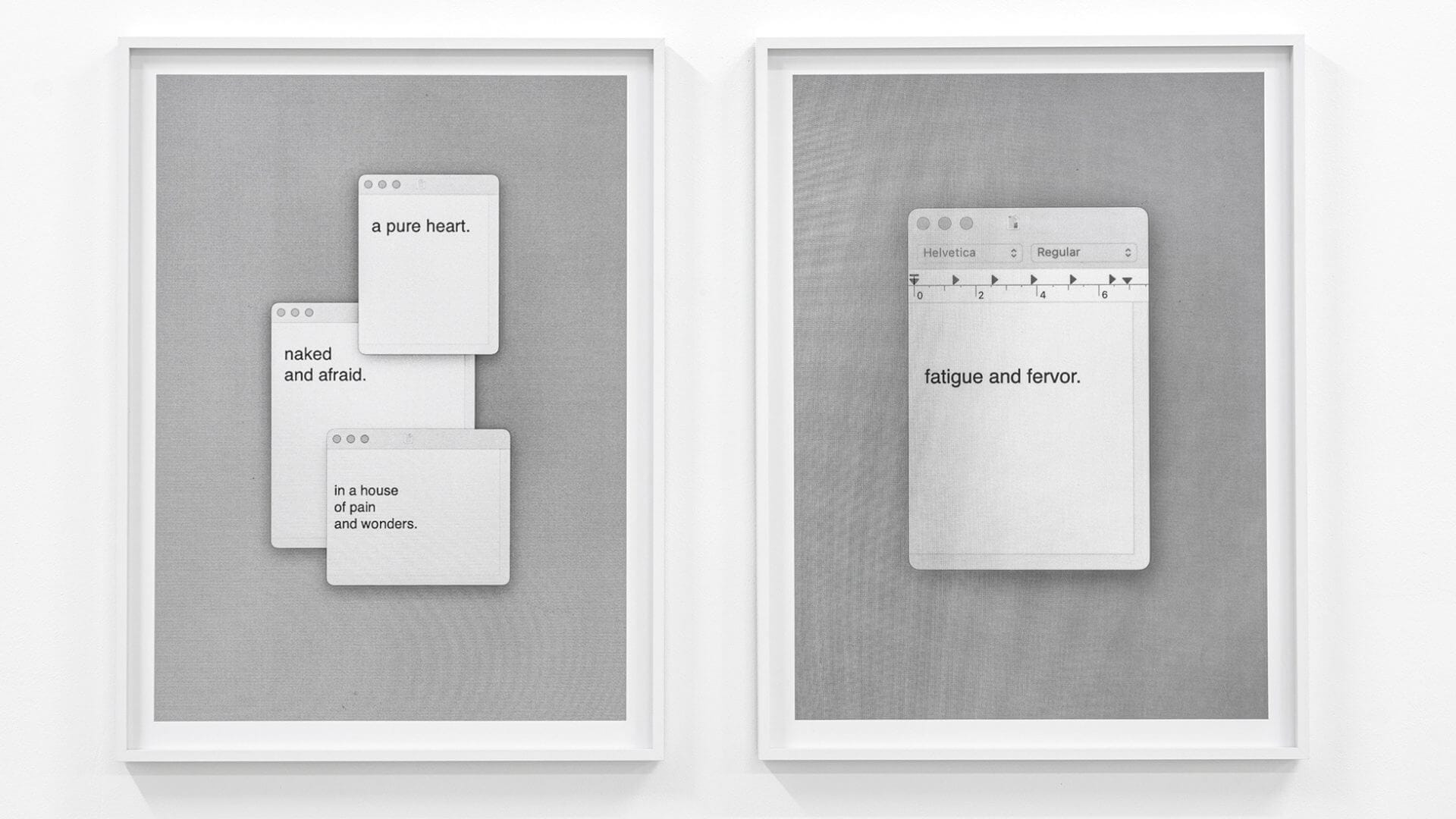

Samuel Henne, untitled (note to self) at ad/ad – Project Space, Hannover

untitled (note to self) by Samuel Henne, curated by ad/ad – Project Space, at ad/ad – Project Sp

WUF Basel 2024: Solo Press Showcases Curated by Fakewhale

On June 11-12 WUF will be hosting an invite-only event for the press at Bar Rouge, Messepl. 10 Basel