Fakewhale in dialogue with Markus Sworcik and René Stiegler

Markus Sworcik and René Stiegler, known collectively as StieglerSworcik, strive to translate the complexities of memory and everyday life into symbolic and often paradoxical forms. Their work invites the viewer into an ongoing process of recontextualization, where meanings are continually shifted, dissolved, and rebuilt. Central to their practice is the idea of deterritorialization—breaking down the fixed boundaries between space, memory, and the viewer’s own perception. With a strong focus on the technology that surrounds us and its effects on the modern human, they try to reflect on current times.

Their exhibitions challenge conventional artistic categorizations, using contradictions, errors, and speculative narratives as essential components of their expression. Whether it’s through immersive installations or collaborative curations, StieglerSworcik’s work oscillates between the deeply personal and the universally unsettling. With a fascination for the everyday and a penchant for dismantling familiar structures, their art opens up new spaces of meaning, demanding active participation and reflection from the audience.

We at FakeWhale had the pleasure of speaking with them to explore the intricate layers of their creative process, their reflections on memory, and their vision for the future of art in an ever-evolving world.”

Fakewhale: Your work consistently explores the transformation of everyday observations and emotional states into symbolic forms. How do you select which aspects of everyday life to translate into your artistic practice, and how do you decide what emotional resonance should be woven into these symbolic representations?

MS: Our process revolves around distilling the everyday life, a practice shaped by what catches our attention or resonates on a deeper level. It’s about how certain perceptions linger with us, shifting from raw experience into something more concrete. Often, the body becomes a vessel for this, absorbing and transforming fleeting moments into meaningful, digestible pieces.

When it comes to selecting what aspects of life to translate into our work, there’s a certain element of anarchy in how we approach it. We actively question dominion—over spaces, forms, materials, and technologies. This isn’t about chaos for its own sake, but about disrupting the conventional ways we relate to these elements. The process is fluid, blending questioning, deep research, and the eventual release of control. Sometimes things take shape quickly, other times they don’t, and ideas can just as easily be abandoned. It’s about embracing a spontaneous awareness of what carries emotional weight at that moment, without forcing it into rigid structures.

The concept of memory recontextualization is central to your work, where memories are continually rearranged to generate new meanings. How do you approach this process of rearranging memory in a way that allows for both personal and collective interpretations to coexist?

RS: We try to form daily observations and emotional states into something. Central to this is a curiosity about the everyday, which serves as the basis for complex memory structures. Cluttering of distracted thoughts, mixed with emotionality and memories is the weather in our head, which spreads in different forms to people. We have realized while working on projects, that the collective perception will be generated anyway and in rather random ways. So generally, the personal interpretation is primary—letting go of expectations in this process is hard enough.

We focus less on the documentation of reality itself than on attempting to renegotiate meanings in an open, ongoing process. Facing decay as a function of time is the most universal commonality of all. Everyday life thus becomes a stage that forms the basis for our practice through our filters and the constant change inherent in the world.

MS: I would add that we’re also drawn to navigating through observation rather than getting lost in the overflow of information, though we still consume it a lot. It’s not about immediate reactions but rather letting things settle and recur over time. It’s similar to using an equalizer—some memories or details come through strongly, while others fade into the background, only to resurface when needed. These latencies, these recurring echoes of past experiences, are something we find fascinating. They shape our work in ways that feel both deliberate and instinctive, like a slow-burning process where saved memories transform into something new when they reappear.

RS: I think of it similar to a technique also occurring in psychotherapy. You are consciously looking for recurring thoughts which are thrown at you from your unconscious, and then you focus on exactly that.

Your method has been described as a form of metabolism, where arbitrary observations merge with conscious practice. Could you elaborate on how this “metabolism” functions in your creative process and how you maintain a balance between randomness and deliberate action?

MS: Our creative process thrives on the interplay of spontaneous observations and intentional practice, which we consider a form of metabolism. We integrate diverse elements—objects, narratives, and forms from our everyday environments, including for example nature, technology, pop culture, etc…—transforming them into new expressions. While we consciously release the constant flow of information, fragments remain in our subconscious, seeking translation into tangible forms. This ongoing process prompts us to question our motivations, balancing randomness and deliberate action.

The line between accident and intention blurs, with both playing vital roles in our work. As a drummer, I memorized compositions while embracing improvisation and the acceptance of mistakes, reflecting this dynamic metabolic flow in our art.

The notion of deterritorialization—dissolving fixed meanings and boundaries—is crucial in your work. Can you describe how this process influences the spatial and emotional structures in your installations? How does this dissolution extend to your audience’s engagement with the work?

RS: It is the attempt to always see things in a different context, no matter if it is material, perception, dialogue, rules etc… Art should be liberating not restrictive, that is at least the hope. The dissolution of boundaries extends to the viewer, who has to actively position themselves in the works without ever remaining in a clearly defined role. It is a help to feel oneself and the state one is in, questioning what is going on. Comparable to a dynamic movement, oscillating between reflection and immediate experience.

MS: We understand deterritorialization as a disruption of spatial, bodily, and material constructs, unsettling established systems to cultivate an openness to the unfamiliar. While rooted in older ideas, it continues to resonate, dissolving traditional frameworks and inviting fluid interpretations that transcend fixed boundaries.

In “Gedunkelfloxx Obsidian,” you explore cryptic sensations within familiar yet paradoxical environments. How do you construct the tension between the familiar and the unsettling, and what do you hope the audience experiences when confronting this “nebulous darkness”?

RS: As the conversations between me and Markus tend to steer always to the psychological and existential, the C.G. Jung term of the “shadow” has been very prominent. The question of what steers me personally and all of us is an important one for us. We find the opposites of “heimelig” and “unheimlich” better suited, and it simply describes things that you know and do not know – which is in our opinion key for good art making.

MS: We often talk about inner states, evoked emotions, and behaviors. The psychological aspect gives us a foundation to work from. We’re definitely drawn to darker themes—they naturally intrigue us more. In a way, we’re aiming to evoke these emotions, to stir up that internal friction. People seek that, consciously or not. There’s this secret fascination with discomfort. Even though we try to avoid pain, there’s something undeniably compelling about it.

Gedunkelfloxx Obsidian is, in a sense, a stand-in for that tension. It represents the friction we feel, a reminder that we’re constantly surrounded by these occupying forces—whether it’s fast-evolving technology, tragic events, or layered personal dramas. It brings us face-to-face with the unsettling. As the philosopher William James said, ‘We do not weep because we are sad, we are sad because we weep.’ It’s that emotional pendulum—our emotions swinging back and forth, driven by the experiences we can’t quite escape.

“Mechanisms of Occupant Ejection” speaks to a sense of perpetual movement and instability. How does the interplay of speed and the fragmented nature of modern existence manifest in this work? Do you see the experience of disorientation as a key theme in your exploration of modern life?

RS: Disorientation and reorganization, today in shorter and shorter intervals, shape almost everything. For us, it also shapes the work we make. The film “Crash” by David Cronenberg was the starting point for “Mechanisms of Occupant Ejection”. This movie revolves for us around rampant manners in a world that seems tamed for the protagonists. Constant movement doesn’t just seem to be a symptom of our society, it’s inherent in us, and we try to accept that in our work.

MS: Also there’s this persistent longing for slowing down, even though it remains a deeply rooted, yet unfulfilled desire. In this case, disorientation became a nostalgic but necessary tool to trigger a particular state of mind. We found ourselves focusing on all the memories and feelings tied to driving—a kind of reflection on a story from our lives that, in truth, could be anyone’s story. It’s represented through objects, some lost, some found, carrying a sense of both absence and presence.

“…I don’t know how long we’d be like that, but it would be fast. Fast like a catnip drip or an auto chase, like driving off the two-lane highway at the speed of the wind. Fast like taking the middle turn off that freeway where I wish we’d crash into each other, but now the freeway splits right before us into two, we’re driving on the wrong one, in the middle of the night, just letting the speed of thoughts take us where we’d go, and because we can.

The charging seatlessness through 5 seconds of sailing, stopping, retuning, and into the tunnel— all in a seemingly lucid, serene movement, in a trance. No shame in going back and forth in thoughts… what is done is done. Such delight. Again. Its gestures interrupted this ruthless system. You can’t stand still for too long.” —Text “Mechanisms of Occupant Ejection”

Your works often operate in a space of contradictions and paradoxes, refusing clear categorization. How do these contradictions function in the larger narrative of your practice, and how do you navigate the challenge of keeping these opposing forces in harmony?

RS: We deliberately avoid clear categories and try to use the said contradictions, paradoxes and errors as essential building blocks for expression. We try to grasp the complex aspects of existence—not as clear answers, but as open questions that continually arise in new constellations. We in no way see these opposites as something that needs to be reconciled. Likewise, we often intentionally combine things that don’t fit together in a harmonious way. The goal is not harmony or beauty, but rather the triggering of a feeling.

The use of text and speculation in your exhibitions often serves as a starting point for your interventions. How do you see the role of speculative writing in your process, and in what ways does it influence the materialization of your artworks?

RS:What begins with speculation and phantasms—often in text form—takes shape and develops into interventions that make inner structures visible. Writing holds other potentials that physical material, for example, does not contain. Furthermore, this can also be understood as a kind of cartographic exploration. These “maps” serve as a starting point for our work—a decoding of the unknown that opens up alternative worlds and aesthetic forms. These worlds may not be real, but through targeted staging they open up new possibilities for how we can think about space, form and materiality. Through speculation, new possibilities arise in the material that go beyond the obvious. Mistakes have the chance to represent something final and are not seen as some kind of enemy. In this flexible, almost fleeting way of working, art is not viewed as a closed, absolute space, but as a living process that is constantly and almost limitlessly reconfigured.

In “A terrible doorstop,” you engage with themes of limbo and intrinsic emotional states. What inspired this exploration of threshold spaces, and how do you think the improvisational nature of your work contributes to the depiction of societal and psychological tipping points?

MS: Basically, we had the idea for a duo exhibition and were looking for a shared arc or overarching theme. We viewed the space as a body we stumbled into, existing in a loose, undefined state. This quickly led us to the concept of liminality, which also reflects a broader social condition—one that describes a non-functioning state. We were searching for a common denominator here. It’s about a symbolism that can flow in spontaneously, intentionally, or even in terms of banality. Whether this “state” reveals itself was not our primary concern.

Technology plays a recurring role in your exhibitions, often symbolizing both a disruptive and influential force. How do you view the relationship between technology and the emotional worlds you depict, and what do you think this relationship reveals about contemporary existence?

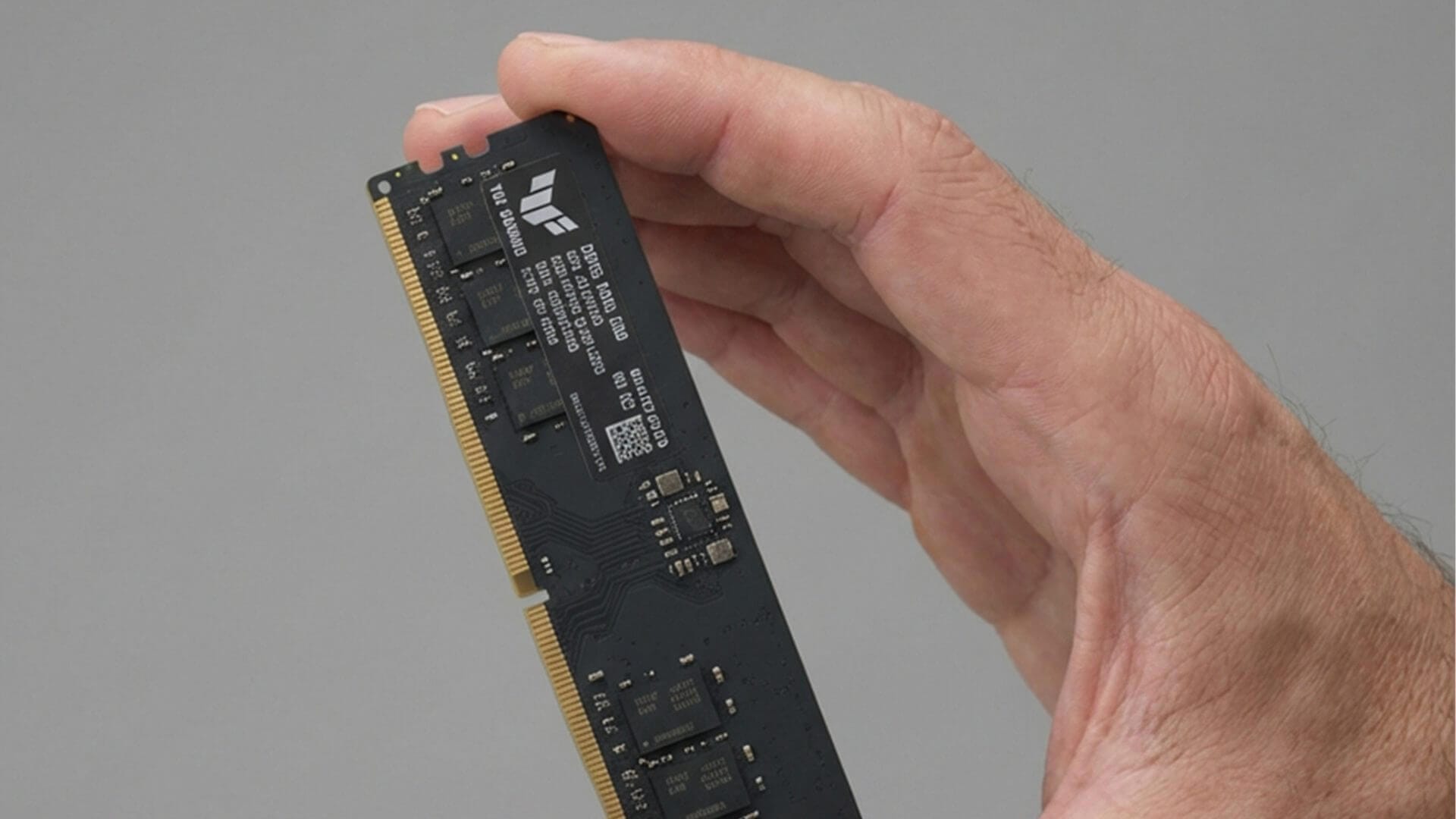

MS: It is true that technology somehow plays a central role in our exhibitions, acting as a disruptive and influential force, even if it only manifests itself symbolically and divergently in the form of objects, materials and space. On the one hand, technology can lead to disconnection and isolation, reinforcing feelings of loneliness in a hyper-connected age. On the other hand, it offers new possibilities for expression and connection, allowing us to explore complex emotions in ways that were previously unimaginable.

This relationship reveals much about contemporary existence. We live today in a world where our emotional experiences are often mediated by screens, where digital interactions can feel more immediate but less authentic. This dichotomy highlights the tension between our innate desire for connection and the artificial environments we sometimes inhabit. We often find ourselves forcing new ways of representation and translation to depict this entity.

Your exhibitions often require active participation from the viewer, yet they maintain an elusive and undefined role for them. What strategies do you employ to ensure that this dynamic participation remains fluid, and how do you anticipate the viewer will navigate the ambiguity present in your works?

MS: We leave the viewer with the possibility to engage with the works at varying speeds. However, we ourselves reflect freely and independently, even unconsciously, on how we react to the pieces. At the forefront is the scenic aspect, along with an accompanying theatricality, to create a vivid overall image. What is depicted could suggest a narrative, where time itself can be transcended.

The imagery in your work, such as the fragmented visions in “Gedunkelfloxx Obsidian” or the chaotic states in “A terrible doorstop,” often evokes a dreamlike or surreal quality. How do you harness the subconscious in your artistic process, and in what ways do you think this enhances the emotional impact of your installations?

RS: The works can be seen also as psychological reflection, where the unconscious is always present. Through intensive exchange mutual issues arise, which simmer below the surface. Things such as dreams and the myth of the simulation can be seen as translation of unconsciousness and wants. This constant internal battle of conscious and unconscious drives us, keeps us on our toes.

Both of you have worked extensively together to curate exhibitions and create collective works. How do you manage the collaborative aspects of your artistic practice? How does the dialogue between the two of you shape the final outcomes of your projects?

RS:Dialogue acts very similar as the text starting points and is often the very first step. Talking about certain imagery scenarios evoke feelings which motivate action. A collaboration has always its highs and lows, and we try to accept that and use also difficult times as a source for creation. Acceptance is indeed a major part of our work, referencing back to the unconscious and trusting the flow of thought, a trust of instinct.

MS: Imagination plays a big role for us, especially when it comes to mapping out the space within a scenario. It often helps shape a complete installation and guides our next steps. We’re drawn to the idea of using unconventional spaces as a primary starting point. It’s about balancing different elements—whether it’s our work, the works of other artists, or the whole process of installing, while keeping an eye on possible open scenarios that might emerge. But the most important thing is staying completely open to different thoughts and ideas as we move forward.

Looking ahead, how do you envision the evolution of your practice in response to emerging cultural and technological changes? Are there specific new mediums or themes you are eager to explore in future projects?

MS: In some contexts, there are countless opportunities to experiment with new materials and technologies. We’re constantly seeking out different modes of expression, especially through our research. It’s less about responding directly to cultural phenomena, which are always shifting, and more about capturing a deeper, underlying mood—a kind of societal pulse that subtly shapes the body of our work. This becomes a form of representation in itself.

For us, the exploration of technology goes beyond just innovation; it includes embracing mistakes and glitches, using them as creative tools. Looking ahead, we’re excited by the idea of reinterpreting classical materials in contemporary spaces, discovering new possibilities in the context of exhibitions and environments. These spaces offer a playground where the tension between old and new can unfold in unexpected ways.

RS: I think we will maintain our independent exhibition style and venture into other media with a bold, scenic approach. Trying to connect to a deeper human experience when creating and perceiving the work.

fakewhale

Founded in 2021, Fakewhale advocates the digital art market's evolution. Viewing NFT technology as a container for art, and leveraging the expansive scope of digital culture, Fakewhale strives to shape a new ecosystem in which art and technology become the starting point, rather than the final destination.

You may also like

The End of Function

The acceleration of artificial intelligence models is commonly interpreted as a threshold of loss: l

13 – Family Reunion and the Death of a Dream

Somewhere in the Forest, Montana, United States Patrick Kibby and Stacy Dasher happened upon a depra

Bytes, Data, Backups, Uploads, Reviews, Photographs: The Role of Documentation and Preservation in Contemporary Art

We might say, exaggerating just a little and using this as a provocation to open the article, that a