Fakewhale in Conversation with Luna Woelle: Bridging Art and Technology

We’re excited to chat with Luna Woelle, a Slovenian 3DCG artist and DJ currently based in Tokyo. After graduating high school in Ljubljana, Luna moved to Japan to study traditional Japanese cuisine. Her fascination with Kaiseki presentation eventually led her back to digital art during the pandemic, where she began experimenting with abstract forms, hard-surface modeling, and developed her “Imaginary Robotics” series. Luna’s work has been featured in Japan, Berlin, Miami, and Slovenia, and she’s collaborated with brands like CASIO G-SHOCK and YAMAWA. Beyond visual art, she performs internationally as a DJ and co-founded an experimental music label. We’ll explore how her diverse experiences have shaped her creative journey and get her take on the intersection of art and technology.

Fakewhale: Luna, transitioning from graphic design in Slovenia to studying Japanese cuisine in Tokyo is quite a shift. How did this change come about, and how has it shaped your artistic career and aesthetic vision?

Luna Woelle: Growing up close to a Japanese family in Slovenia, I developed an early interest in Japanese culture and cuisine. Both parents in that family were chefs, which started my obsession with Japanese food when I was just two years old. As I got older, my fascination gradually shifted towards the visual aspects of food presentation. During my time studying graphic design in secondary school, I explored this interest even further. Eventually, I earned a Japanese government scholarship, which allowed me to move to Tokyo right after my high school graduation.

I spent two years at Hattori Culinary College as part of a three-year program, where I earned top honors in my traditional Japanese culinary major. While I appreciated the experience, I realized early on that I was more drawn to the visual side of things, and continued to work on my digital art alongside my culinary studies. The detail and harmony in Kaiseki presentation have deeply influenced my approach – I try to apply the same careful precision I learned during my culinary studies to my work, modeling each detail and object from scratch before assembling everything into a cohesive piece. This allows me to fully immerse myself in the creative process, while still giving myself enough room for experimentation.

After training in graphic design, what prompted you to explore the field of 3DCG, and how did you develop your skills in this discipline?

After learning the basics of Blender in high school, I used it for a realistic restaurant plan as my graduation project. Frustrated by the lengthy process, I set the software aside after finishing the project. However, during the pandemic, I felt the urge to create again. My abstract work in Photoshop started resembling 3D forms, which encouraged me to revisit Blender. This time, I focused on experimentation rather than strict guidelines. As I grew more comfortable, I moved onto hard-surface modeling and started exploring complex structures, eventually leading to my “Imaginary Robotics” projects.

After the pandemic, your work returned to digital art. What were the first projects you created during this period, and how did they evolve your artistic style?

After experimenting with 3DCG, I initially focused on event flyer designs and edits, which I began receiving commissions for through Instagram. These were great as a medium and means to explore and evolve my approach, as I simultaneously created 3D visuals for my DJ sets, focusing primarily on organic shapes and textures. Over time, I transitioned from these early projects to more complex hard-surface modeling, eventually merging abstract experimentation with technology to develop the “Imaginary Robotics” series.

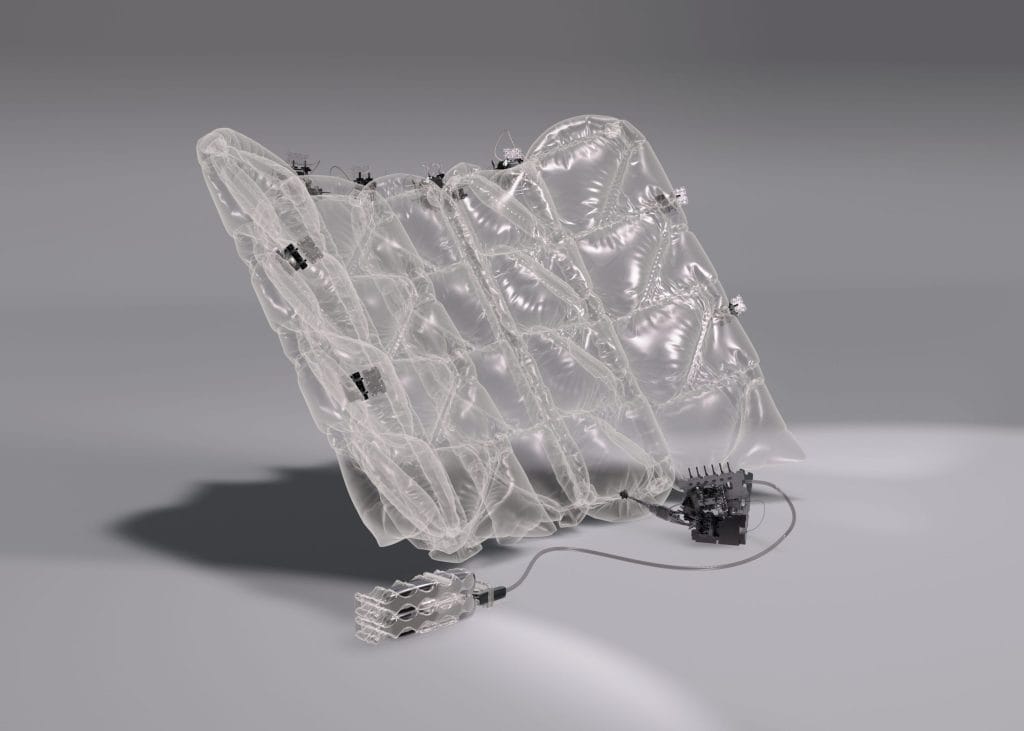

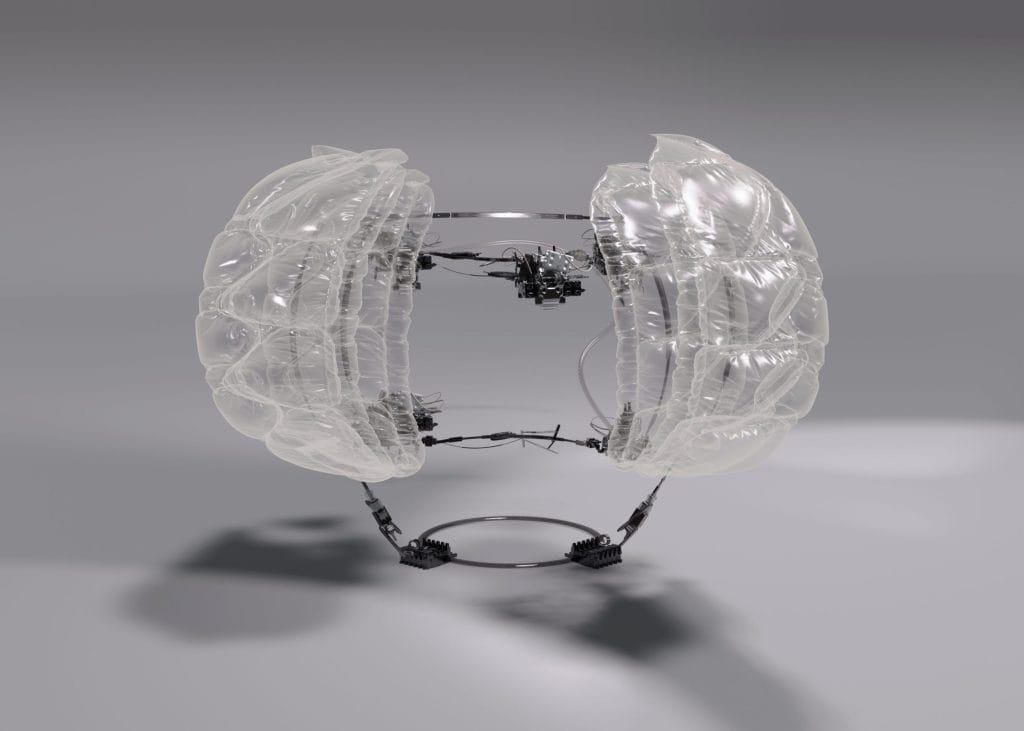

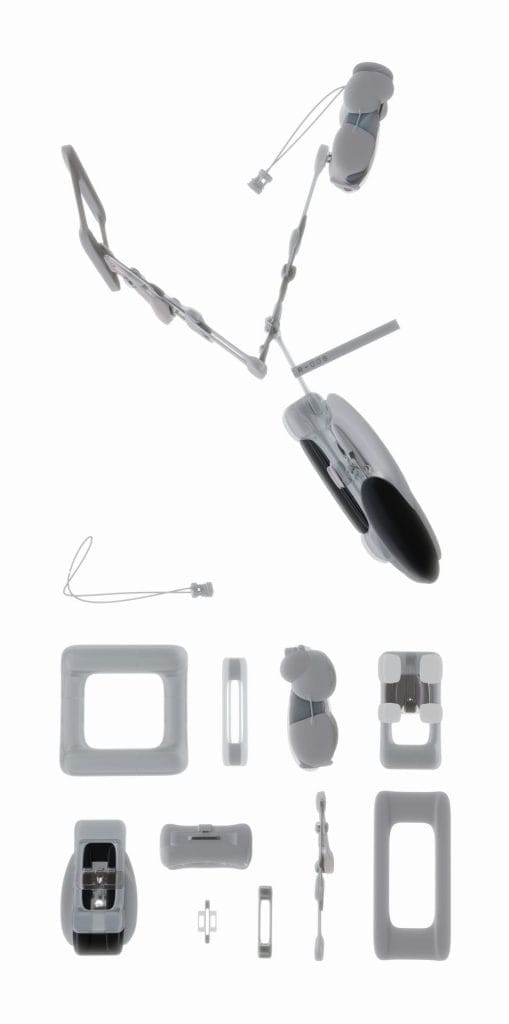

Your “Imaginary Robotics” works reflect a critique of consumerist capitalism. Can you delve into the motivations and messages behind these works?

“Imaginary Robotics” started from my interest in combining mechanical and organic elements. I create objects that seem functional but are actually useless, embracing the idea of producing intriguing, purposeless objects meant only for display. These works reflect how consumer goods give us short-lived dopamine highs but often leave us wanting more, prompting us to reflect on our relationship with technology and how it shapes our experiences.

How has life in a technologically advanced metropolis like Tokyo influenced your works and your perception of technology?

Living in Tokyo has significantly shaped my work and how I view tech. I’ve come to rely on it, and honestly, there’s no turning back. It feels good to be part of something bigger, and I can easily get lost in this tech-driven, overly convenient world. Through my work, I explore these feelings, whether it’s the irony of guilt or simply embracing a world driven by functionality and aestheticism.

Your critique of capitalist society emerges through your work with objects that appear robotic but have no function. How do you hope the audience interprets this contrast?

I hope the audience sees this contrast as a commentary on our consumerist culture and the superficial nature of many capitalist goods. By creating objects that look functional but have no real purpose, I want to highlight the emptiness and insecurity that often accompany our pursuit of material possessions. I aim for the audience to reflect on their own relationship with technology and consumerism, and perhaps question the true value of the objects they rely on.

How do you navigate the complexity of translating your artistic vision into design work for major brands like CASIO G-SHOCK?

It’s not easy. On one hand, incorporating my artwork into commissioned projects feels like a validation of my creative approach and an opportunity to introduce my art into new contexts. On the other hand, things can get complicated when my role becomes purely that of a visual designer, and I lose some freedom and credit. It’s a balancing act between my artistic identity and client needs while keeping my creative edge intact. That said, I’m always open to collaborations and commissions—they’re crucial for supporting my work and exploring new creative directions.

How does your experience as a DJ and your connection to music influence your visual art and vice versa?

Basically, it’s a continuous loop of mutual influence. My work as a DJ, especially with experimental music, directly feeds into my visual art. The dynamic range and emotional depth of the sounds I experiment with inspire my creative process, adding rhythm and movement to my designs. Conversely, my art shapes how I approach music, pushing me to explore unconventional sounds and structures.

Looking ahead, what upcoming projects are you working on?

At the moment, I’m focused on expanding my IR series and continuing to create objects as an art form. Ultimately, I hope to bring them to life and experiment with installations. For now, I’m concentrating on capturing different shapes and textures through animation as a way to exhibit them digitally.

fakewhale

Founded in 2021, Fakewhale advocates the digital art market's evolution. Viewing NFT technology as a container for art, and leveraging the expansive scope of digital culture, Fakewhale strives to shape a new ecosystem in which art and technology become the starting point, rather than the final destination.

You may also like

Fakewhale in dialogue with Alex Hartley

In his most recent body of work, Alex Hartley appears to undertake an operation that is as physical

Fakewhale in Dialogue with Jacopo Benassi: The Visceral Tension of an Uncompromising Vision

Fakewhale had the pleasure of speaking with Jacopo Benassi, a multifaceted artist who moves fluidly

MOCA 2023 Fundraiser: In Conversation with Colborn

From its founding in 2020, The Museum of Crypto Art (M○C△) has been a pivotal force in the evolu