The Spectacle of the Void: Art Without an Object

In the most extreme forms of conceptual art, the artistic gesture tends to vanish, dissolving into the thought that generates it. The “invisible artwork” emerges as both paradox and provocation, a declaration of war. It offers no object, no image, no body to contemplate, only an idea that endures through its own disappearance. This is an art of absence, of traces, of promises left unfulfilled. An art that exists through its own withdrawal.

In 1958, Yves Klein opened a now-legendary exhibition at the Galerie Iris Clert titled The Specialization of Sensibility in the Raw Material State into Stabilized Pictorial Sensibility, better known as The Void. The gallery was completely empty. But Klein didn’t stop at the physical absence of the work, he staged a full-blown vernissage with a red carpet, Republican Guards, and champagne. The event became a theatrical mise-en-scène, a symbolic act that magnified the evocative power of nothingness. The artwork was the void itself, orchestrated as a celebration of pure sensibility. To promote his next exhibition, Klein commissioned a photograph of himself seemingly leaping into the void from a Parisian window: Le Saut dans le vide (1960). In reality, the jump was a photographic illusion, a montage. Once again, the action never truly happened, but it existed as a mental image, as provocation.

This tension between presence and absence reappears in more recent works, such as those of Florence Jung, an artist who has built an entire practice around intentional invisibility. Her pieces, often titled with numbers like jung58 or jung89, are rarely documented. They cannot be seen, purchased, or preserved. These are ephemeral actions, unannounced, sometimes even unsuspected. In one piece, she hired a person to cry convincingly in a shopping mall for a set period of time. The work wasn’t recorded or traceable, it lives only in the uncertainty of those who may have witnessed it. In jung45, Jung subtly altered a gallery’s playlist by inserting a track that subtly unsettled the environment, without notifying anyone. Once again, the art hides in the margins, in the interference.

This act of concealment echoes earlier works like Joseph Kosuth’s One and Three Chairs (1965), where the physical object is interrogated by the idea, the language, and its representation. Or John Baldessari’s I Will Not Make Any More Boring Art (1971), in which the work is a performative promise, a mantra repeated as a denial of the act of making.

But the apex of this tension is reached in works that deny their own material existence. In Untitled (A Curse) (1992), Tom Friedman commissioned a Haitian witch doctor to place a curse on a plain white pedestal. The result is a piece that can’t be seen or heard, but “acts” as an invisible threat. Similarly, the entire body of work by Tino Sehgal consists of choreographed situations and conversations activated by the audience, none of which can be photographed, filmed, or documented. They exist solely in the memory of those who experience them.

The “invisible artwork” thus radicalizes a core artistic urgency: to shift art from matter to consciousness, from form to possibility, from object to thought. It is an art that doesn’t aim to exist for everyone, only for those willing to find it where it refuses to be seen.

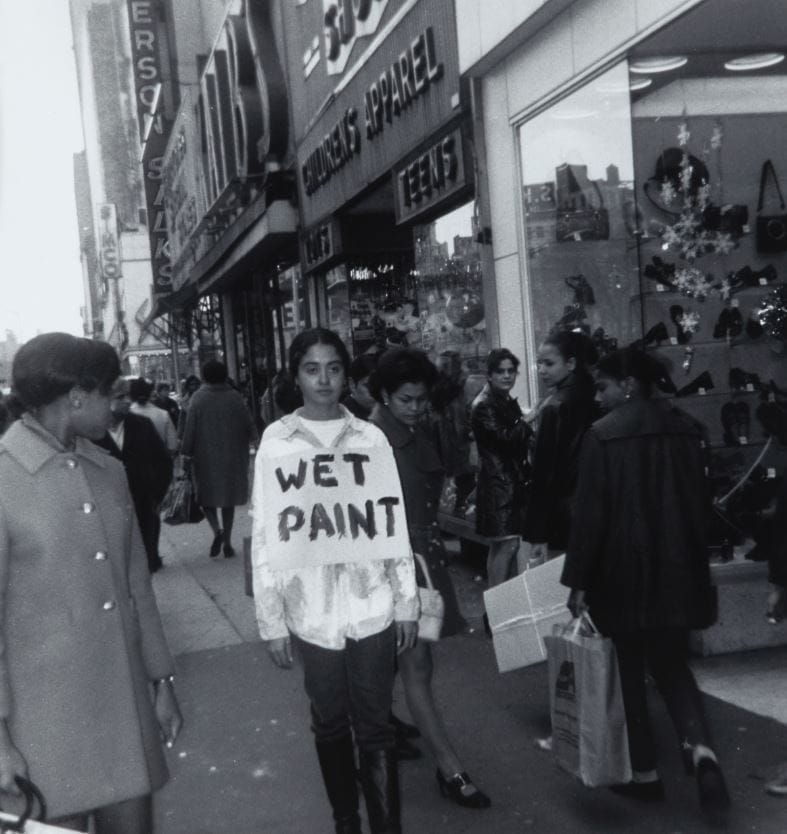

Starting in the 1970s, invisibility became not just an aesthetic choice but also a political stance. Adrian Piper, for instance, in her Catalysis series (1970–1971), performed a set of disturbing and subtly theatrical public interventions, riding a bus with a dirty towel stuffed in her mouth, or walking through the city in clothes soaked with foul-smelling liquids. No one recognized her as an artist. There was no stage, no label. The artwork existed solely in the interference between her and the world, in the short circuit between social expectations and the real body. And it’s precisely this liminal condition, being seen without being recognized, that made her invisible as an artist, yet hyper-visible as disruption.

Around the same time, Chris Burden created 5 Day Locker Piece (1971), in which he locked himself inside a metal locker at a university for five days. No one could see him. There was no visible action, no movement. The audience stood before a closed, silent surface, and the work lay in the awareness of the gesture itself, in the evocative power of the information: “the artist is in there.” A physical presence turned into a visual absence.

In 2005, Gianni Motti presented a “performance” at the Art Unlimited section of Art Basel that consisted of walking through the gallery before it opened—then never appearing again. The title of the work? The Invisible Man. Visitors wandered through the empty space, searching for the work as one might search for a ghost. And perhaps they found it only in their attempt to interpret it.

Invisibility thus becomes not just the content of the artwork, but its form, its operative mode. This is seen in especially sophisticated ways in the work of Santiago Sierra, who often uses budgets and contracts to produce works that are as invisible as they are ethically unsettling. In 160 cm Line Tattooed on 4 People (2000), he paid four drug users to have a single black line tattooed across their backs. The piece was never shown publicly; it was documented only as an idea, as an economic and contractual dynamic. The object had vanished, what remained was the system that produced it.

Another emblematic example is the work of Rirkrit Tiravanija, known for cooking Thai curry in art galleries to feed the audience. Seemingly highly visible, his work actually resides in the relational gesture, the interaction, in what disappears the moment the event ends. No object remains. Tiravanija himself has said: “There is nothing to look at, only something to live.”

But perhaps the ultimate expression of invisibility is reached in the work of Robert Barry, who in 1969 presented Inert Gas Series. In this piece, he released inert gases (like helium and neon) into the air of the California desert. No one could see it. No one could touch it. The only way to know it happened is to believe the artist’s declaration. The work is an act of faith, a suspended belief.

In the new millennium, invisibility is no longer merely a provocative gesture, it has become a widespread strategy, a subtle way of eluding the hyper-visibility imposed by the attention economy. More and more artists are choosing to disappear, to deactivate, to sabotage presence itself.

A compelling example is Mexican artist Mario Garcia Torres, known for his “non-works”, pieces that often take the form of partial reconstructions, orphaned archives, letters sent to closed galleries, or investigations into exhibitions that never took place. In I Promise Every Time (2004), he presents a declaration of intent: each time the piece is shown, he promises to make it again—yet it is never actually presented. The work lives in that cyclical, unfulfilled promise.

Between 2007 and 2012, the French collective Claire Fontaine, which explores appropriation and the crisis of authorship, produced a series of “invisible sculptures.” Some of these consisted of objects stolen from supermarkets or public spaces and reinserted into the gallery space without any indication. The work is not visible, but it’s there, potentially. The tension between legal and illegal, between action and omission, becomes the true form of the artwork.

In 2011, Berlin-based artist Johannes Paul Raether staged an unannounced performance titled Transformella, in which he disguised himself and wandered through technology and biopolitics fairs, posing as a theoretical creature from a dystopian future. No one knew it was a performance. There was no official documentation. Only those familiar with the artist’s alter ego might suspect something. The work existed only in the hybrid space between reality and invention.

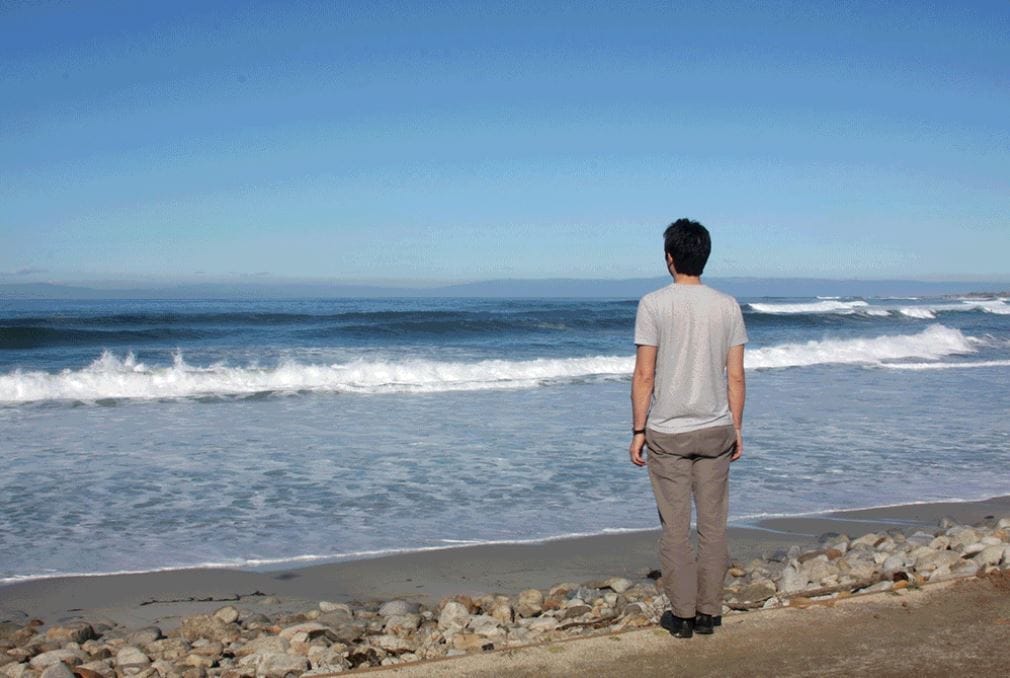

An extreme case is that of David Horvitz, who in 2009 sold poetic actions on eBay, such as “I will walk into the Pacific Ocean fully clothed for thirty minutes” or “I will send you a photograph of the sky taken today.” The works were temporary, ephemeral, and often unverifiable. The collector was buying a gesture, an intention, not an object. In another action, Horvitz placed books in the “art” section of bookstores without permission, but altered with his handwritten notes, annotations, or interventions. These were artworks hidden in plain sight.

More recently, in 2020, artist Sébastien Rémy curated a series of imagined exhibitions, each of which existed only as a verbal narrative, never realized physically. Invitations were sent out, curatorial texts were published, but the exhibition space remained closed. The artwork became an echo, a story, a ghost exhibition that lived in the listener’s mind.

Finally, American artist Valerie Snobeck creates “subtle” and nearly imperceptible works, often using transparent or repurposed materials placed so they blend into their surroundings. Visitors might walk through the installation without even noticing. In some cases, its only presence is marked by a title and a dot on the gallery map. Visibility is reduced to its bare minimum, until it becomes mere supposition.

In an age where everything tends to become content, where every gesture is potentially photographed, tracked, and shared, the invisible artwork gains a renewed power. It is no longer just a conceptual move; we believe it has become a form of active resistance. In the face of the predatory logic of social media, where art is consumed more for its Instagrammability than its depth, invisibility emerges as both an ethical and aesthetic gesture. It is a refusal to participate in the dynamics of the attention economy.

To disappear becomes a political act.

In the silence of the unseen work, in the intentional void left by those who refuse to produce images, a space opens up for reflection, a critical interstice where thought reclaims center stage. The invisible is not empty; it is charged with meaning. It is not absence, but latency. An energy activated by suspicion, doubt, narration.

Today, when every action seems to require visual proof, a document, a caption, choosing to leave no trace is an extreme act, perhaps even a revolutionary one. Of course, to be fully consistent with this line of thought, we would have to start sending out blank newsletters, announcing exhibitions with no works, promoting interviews that dissolve into thin air. And in some ways, we feel guilty, because we keep communicating, and communicating, still!

Yet we continue to dream of the perfect form of the “invisible” artwork, not just one that escapes visibility, but one that undermines the very logic of public validation. A form of art that doesn’t ask for likes, doesn’t seek to be shared, but simply to be thought. And perhaps, in this voluntary retreat, in this radical withdrawal, lies one of the purest, and most relevant, forms of contemporary art.

fakewhale

Founded in 2021, Fakewhale advocates the digital art market's evolution. Viewing NFT technology as a container for art, and leveraging the expansive scope of digital culture, Fakewhale strives to shape a new ecosystem in which art and technology become the starting point, rather than the final destination.

You may also like

Fakewhale in Conversation with Deniz Kulaksızoglu: Exploring Fragmented Bodies and Surreal Spaces

Deniz Kulaksızoglu’s work moves through territories where the exhibition space transforms into a

Fakewhale in dialogue with Marcello Maloberti

With his new project METAL PANIC, showcased at PAC in Milan, Marcello Maloberti transforms the space

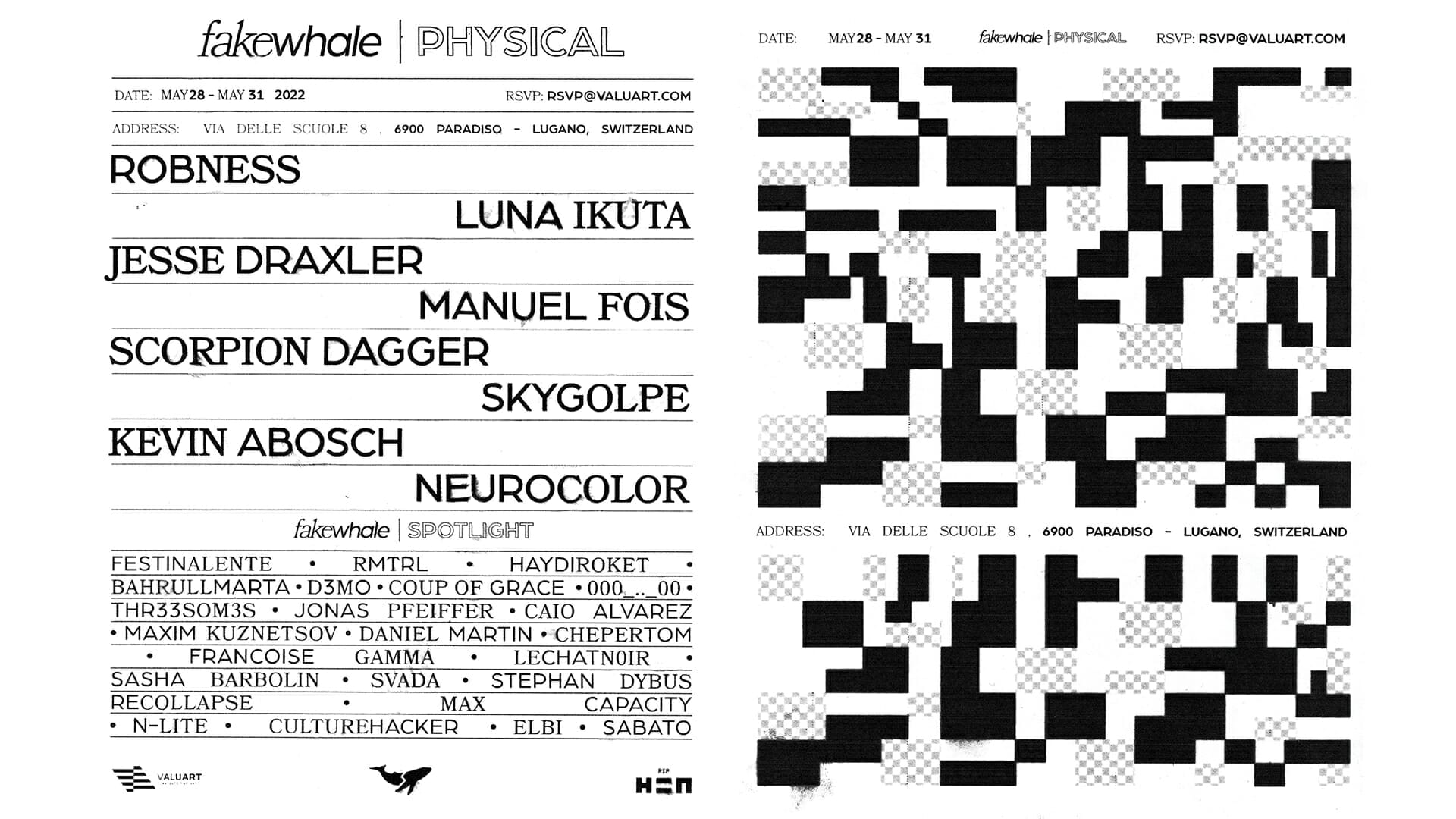

Fakewhale Physical I: The Fakewhale Vault Permanent Collection

At its foundation, the Fakewhale Vault is an innovative curatorial project that aligns the tradition