(New) Ways of Seeing

In the ever-evolving world of arts and culture, the concept of curation has undergone a remarkable transformation. Originating from the Latin word “curatus,” meaning “to take care of,” the traditional role of curators involved meticulous preservation and handling of artefacts within museums and archives. However, the contemporary understanding of curators extends far beyond the realm of caretaking.

They have emerged as imaginative contributors who possess a deep understanding of the sociopolitical commentary that underlies modern exhibitions. In this context, educational institutions are recognising the need to prepare new generations of professionals who can redefine roles within the industry. Within my department of Culture and Enterprise at Central Saint Martins, we have two courses on this topic: BA (Hons) Culture, Criticism and Curation and MA Culture, Criticism and Curation. The curriculum draws inspiration from historical context, political issues, and the future, prioritising interdisciplinary practice, critical theories, and engagement with urgent social issues. The aim is to develop practitioners who are not only committed to advancing arts, culture, and heritage but are also acutely aware of the social and cultural contexts and impacts of their work. Emphasising critical inquiry, and a culture of reflection and active listening, students are offered opportunities to collaborate and engage with diverse practices through curatorial projects and writing.

However, in the modern realm where technology and art intersect, a new wave of curatorial approaches has emerged, challenging traditional notions and inviting both fascination and contemplation. These emerging modes of curation prompt us to question the future of curatorial practice and how professionals in the industry can redefine and renegotiate traditional roles. The evolving landscape of curation demands critical reflection and a proactive approach to adapt to the changing times.

Firstly, let’s dive into this new world, where the true measure of an artist’s worth lies in the floor price of their digital creations. These new ways of curating defy conventional practices, offering a glimpse into a universe where the price becomes the arbiter of artistic selection.

Within this framework, artists are chosen based on their market success, rendering artistic merit a mere backdrop to the allure of financial triumph. In fact, forget about artistic merit, creativity, or thought-provoking concepts. It’s all about the market success, baby! In his review of the latest Picasso exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum for the New York Times, Jason Faraga astutely observes that where the curatorial ambitions are “at the GIF level”, we grant audience the “moral permission to turn their backs on what challenged them, and to ennoble a preference for comfort and kitsch.” Similarly, for group exhibitions, the best practice is to check the floor prices and invite those best-selling artists to showcase their digital masterpieces. Who needs artistry when you have dollar signs? A good therefore theme (excuse) is a charity drop. As Gabrielle Schwarz wrote in her “Bake Sale” piece for Outland, this is yet not new to the traditional art world at all, as the ,philanthropic endeavours are used to make the excesses of money and power that flow through the industry more palatable.”

Next up, we have the revolutionary concept of curating based on medium. Imagine, if you may, an exhibition curated solely around the medium itself—a thematic tapestry woven from the threads of code-based art, generative art, digital art, and the captivating realm of AI art. Picturing the Tate Britain boldly proclaiming an exhibition entitled “Oil Paintings” or The Photographers Gallery in London venturing into uncharted territory with their presentation of “Digital Photography” that elicits both intrigue and introspection. It is as if we witness a transformation, where the very essence of the medium becomes its own gravitational force, commanding attention and validating its artistic significance. And to ensure that no doubt remains, the exhibition title must dutifully bear the imprints of the words “DIGITAL” or “CODE” in a proclamation of its modernity.

In this tapestry of novel curatorial approaches, another thread intertwines—one guided by the discourse surrounding the groundbreaking idea of curating based on gender. No longer confined to the limits of thematic exploration or cultural dialogue, curators venture forth, their invitations extending solely to female artists. An “all-female show” takes shape, its theme shrouded in mystery, as if the very act of identifying oneself as a woman and engaging with the realm of technology becomes the hallmark of artistic distinction. Who needs to think about themes or engage in mentioned cultural dialogue when you can simply send invites to female artists and throw together an “all-female show”? The theme? Oh, that’s irrelevant, it’s TBC. As long as you identify as a woman and have dabbled with a computer, you’re in! Because gender is the ultimate determiner of artistic expression, right? One important digression from this chi-chi trend: there are exceptions. Some all-female shows may dare to discuss important issues like abortion or the female body. In those cases, the invitation is in fact related to the theme and not just a matter of checking birth certificates/ pronouns. In these instances, the selection is thoughtfully aligned with the underlying concept, candidly transcending mere formalities of gender verification.

This shifting landscape of curation, where market forces, medium-based segregation, and gender-focused selection reign supreme, calls into question the very essence of artistic expression. Where once intellectual depth, profound concepts, and the relentless pursuit of pushing artistic boundaries took precedence, we now find ourselves adrift in a sea of new modes of categorisations and token gestures. The age-old appreciation for thought-provoking themes and the relentless quest for artistic ingenuity seem to have been supplanted by the allure of financial gain, superfluous artistic divisions, and superficial gestures towards inclusivity.

As we navigate this brave new world of curatorial practice, where the echoes of artistic coup d’état reverberate in gallery rooms, or conference halls filled with 65 inch Samsung TV screens, we are compelled to ponder the true essence of art. Is it the price tag that validates an artist’s worth? Should the medium itself become the driving force behind our curatorial choices? And can gender alone serve as the ultimate qualifier for inclusion? These questions, as contentious as they may seem, propel us towards a deeper exploration of the evolving landscape of curation and its profound implications for the artistic sphere.

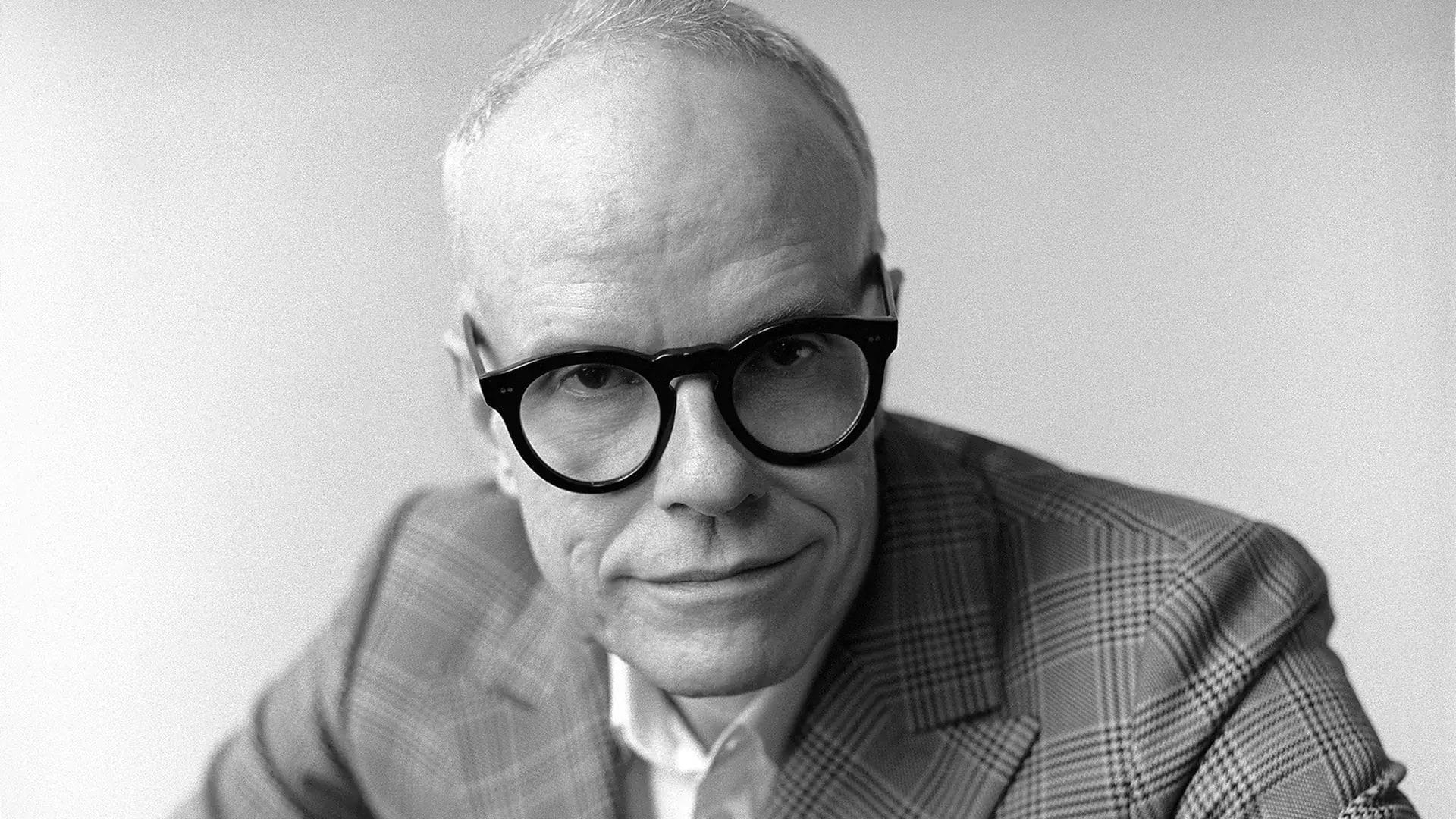

Notable among influential curators is Hans-Ulrich Obrist, the artistic director of Serpentine Galleries in London. In his book, “Ways of Curating,” Obrist reflects on his early experiences and the inherent desire to question the boundaries of the curator’s role. Curiosity emerges as a central driving force behind curatorial practice, fostering a thirst for knowledge and establishing meaningful connections. He even contemplates alternative titles for curators, including “junction maker,” emphasising their role as catalysts, motivators, and bridge builders between artists and audiences. He envisions exhibitions that have a broader impact on society, engaging with diverse communities. Nevertheless, while curating has gained popularity, Obrist acknowledges the risk of dilution in meaning in the digital age. The overwhelming abundance of information and images can result in a loss of significance for the term “curating” unless it is carefully contextualised and executed.

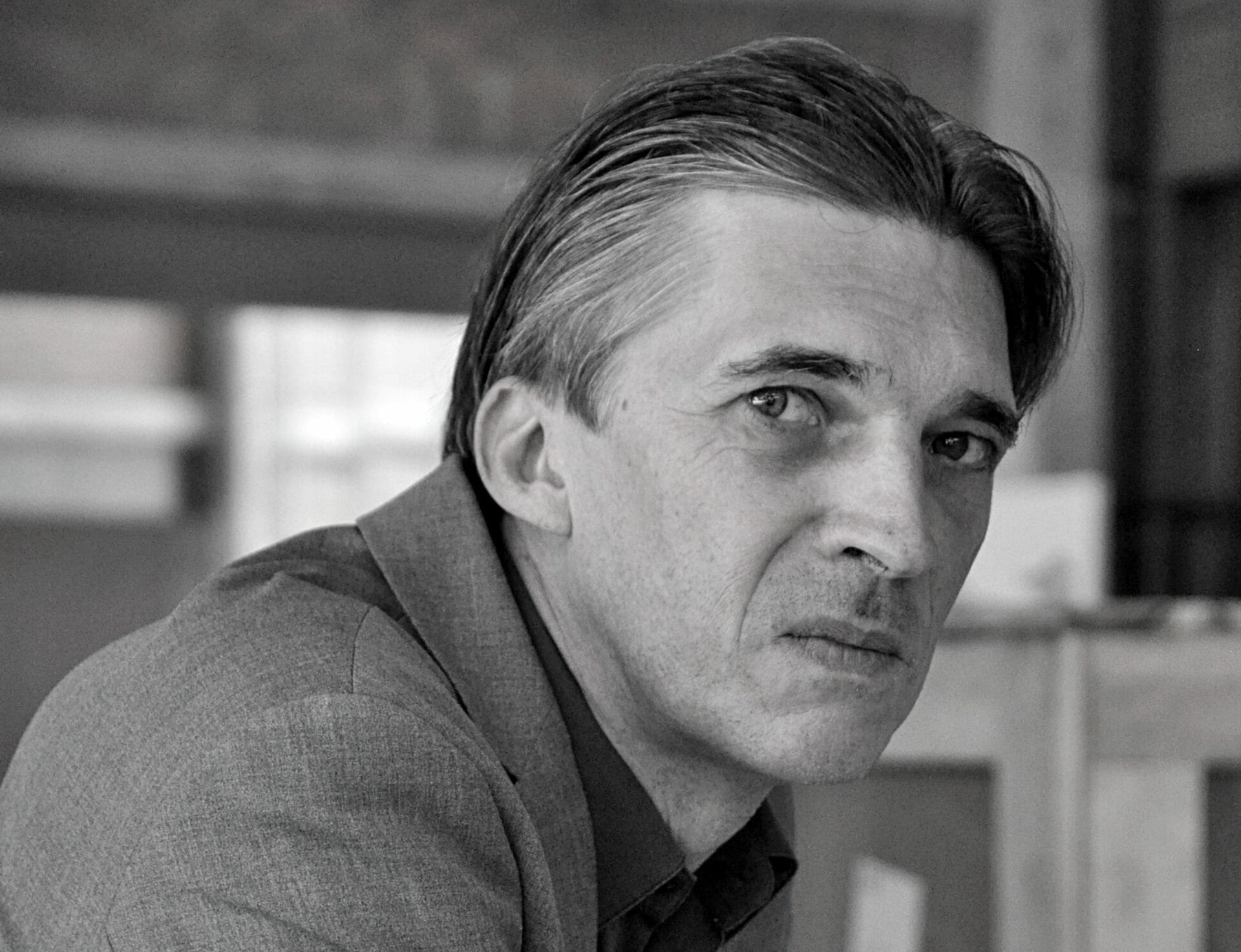

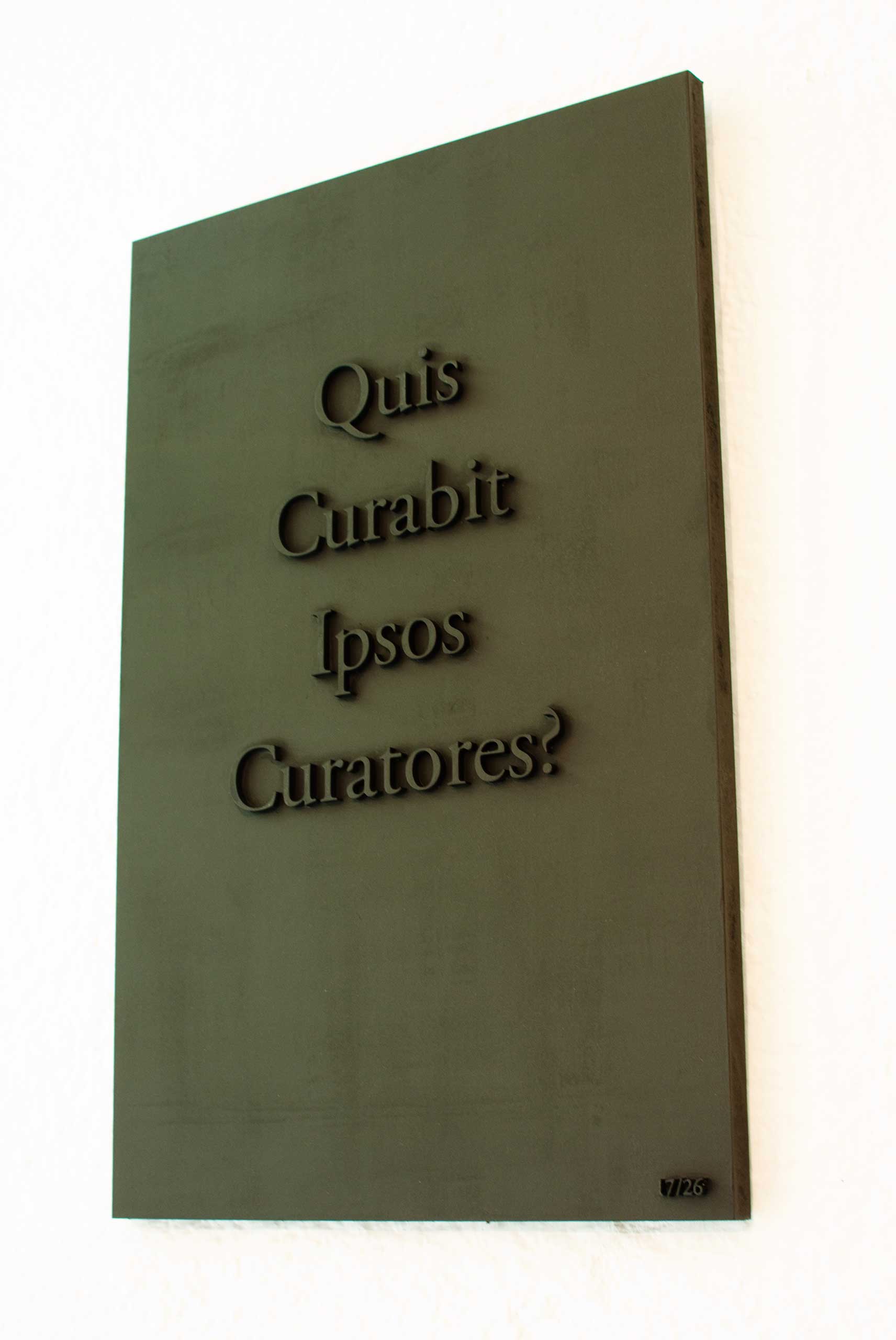

Andrew Renton, a professor of curation at Goldsmiths, shares similar concerns about the saturation and potential devaluation of the term “curating.” In a 2020 NYT interview, he suggests exploring alternative descriptors that better capture the evolving role of curators. He also said that in the era when everyone’s a curator now “the term is so debased that we have to think elsewhere about what to call ourselves?” And there’s one more question, posed in a work from 2011 that Mario Klingemann shared with me some time ago, which cheekily prompts us: “Quis Curabis Ipsos Curatores?”

Mimi Nguyen

Creative Director at verse.works and Assistant Professor at Central Saint Martins, University of Arts London. Her research on creativity and human-computer interaction has been published by Cambridge University Press, Design Research Society and TIME Magazine.

You may also like

Fakewhale in dialogue with Yuki Okumura: On the Subjectivity of Exhibition Space

In his solo exhibition at the Secession in Vienna (March 8 – May 18, 2025), Yuki Okumura transform

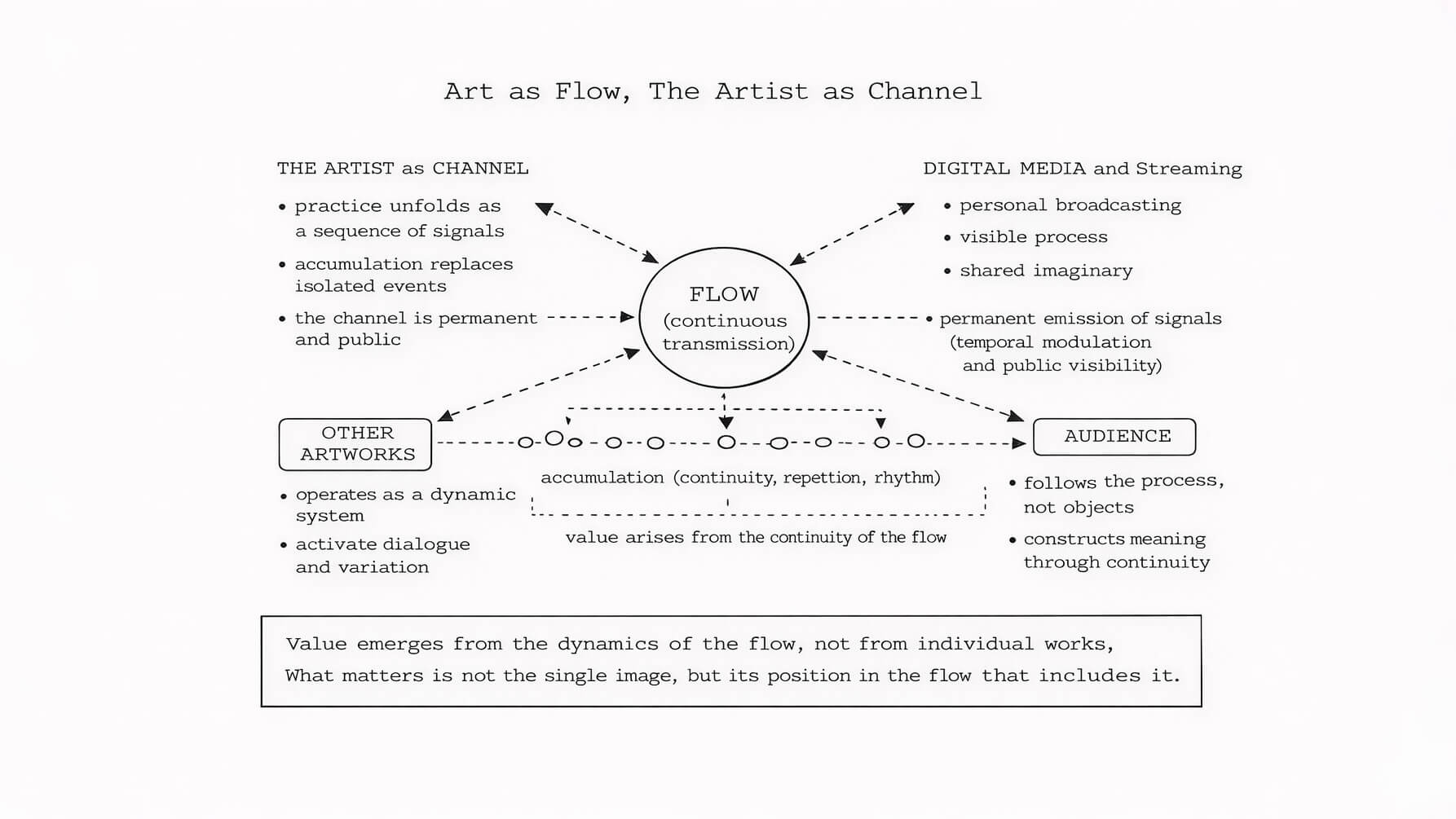

The Artist as Channel

Increasingly, in contemporary artistic practice, the focus is no longer on the individual artwork bu

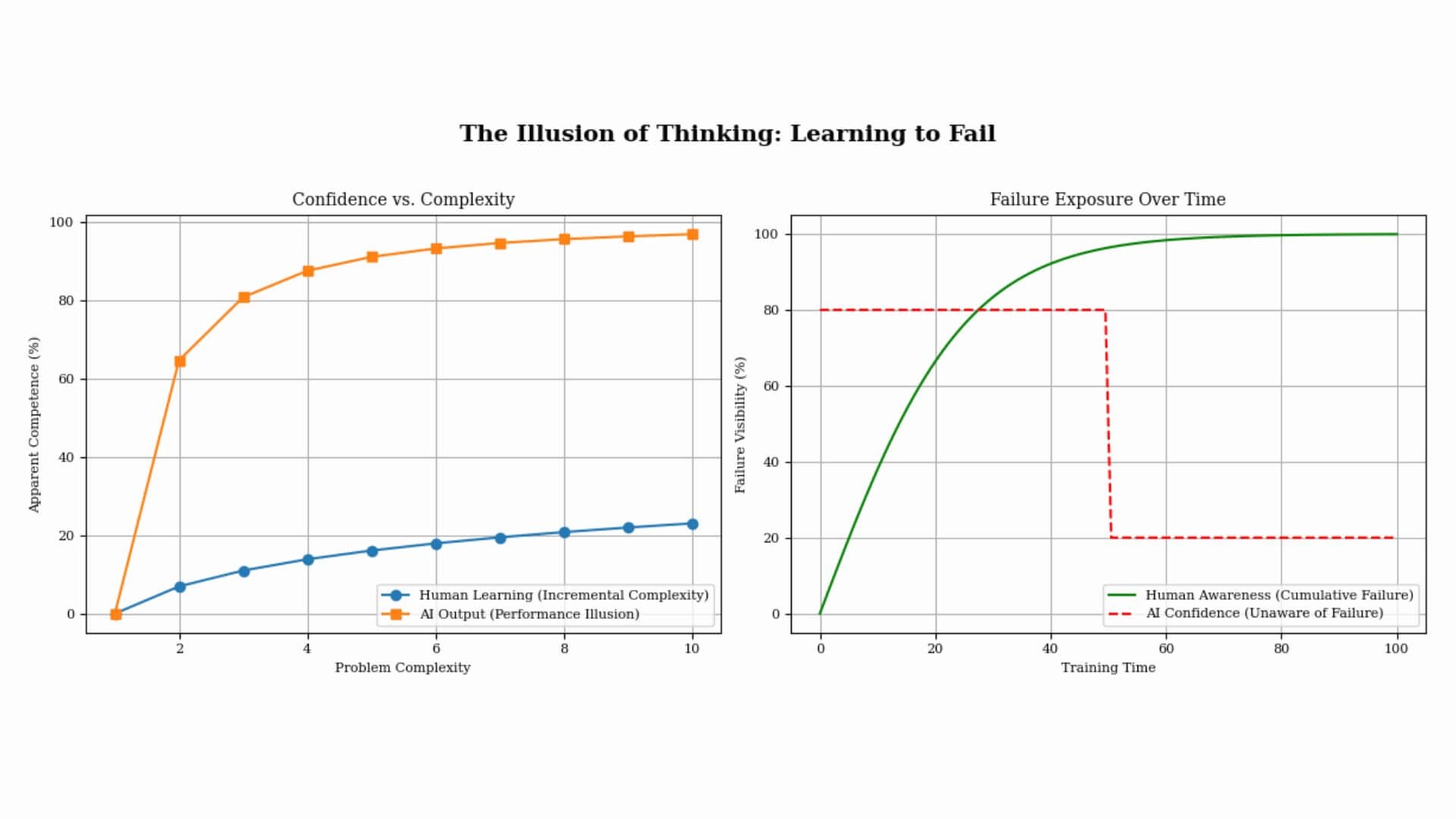

“The Illusion of Thinking”: Learning to Fail

A few days ago, we published The Illusion of Thinking, a speculative detournement of an Apple resear