CTRL+Z: From 1910s to 2010s, and Beyond. A Brief History of LOWTECH

To understand what LOWTECH Art tendency is and what we have been facing in art galleries and online platforms in recent decades, it’s important to take a step back into art history, rewind the film, and try to comprehend the process that has led us to this specific moment in contemporary art, where technology is constantly present, even when the artwork is something as traditional as a painting, since it is photographed and presented online, such as blog posts or installation views.

“CTRL+Z” is the perfect metaphor for this journey into the past. Every day, with our keyboard, we “undo” errors and mistakes, removing an action to return to the original form. In an age in which the possibility of deleting is so easy that even culture and tragedies can be erased or denied, by using this tool, we can delve into the foundational aspects of this movement in contemporary art.

According to Fakewhale’s recent introduction of the term, LOWTECH is «a practice that reframes technology not as a symbol of linear progress but as a space for questioning and redefining sculptural language» [1], which means that it’s not merely the metaphor of progress and innovation, but a tool of self-referential analysis that «emphasize [sic] a sense of transience in their ‘function’, suspended between the operative and the dysfunctional, between a sudden inversion of their intended use and the space they open up for new meaning, where the limits and wonders of technology become a space for critical reflection and creative reinvention»[2].

This tendency is far from being “new”, and actually is rooted in the historical junction of the Avant-Gardes, which are also rooted in the evolution of means like photography or cinema through the 19th century, during the industrial revolution. But let’s proceed in order.

Since the advent of the Avant-Gardes, the relationship between art and technologies was present.

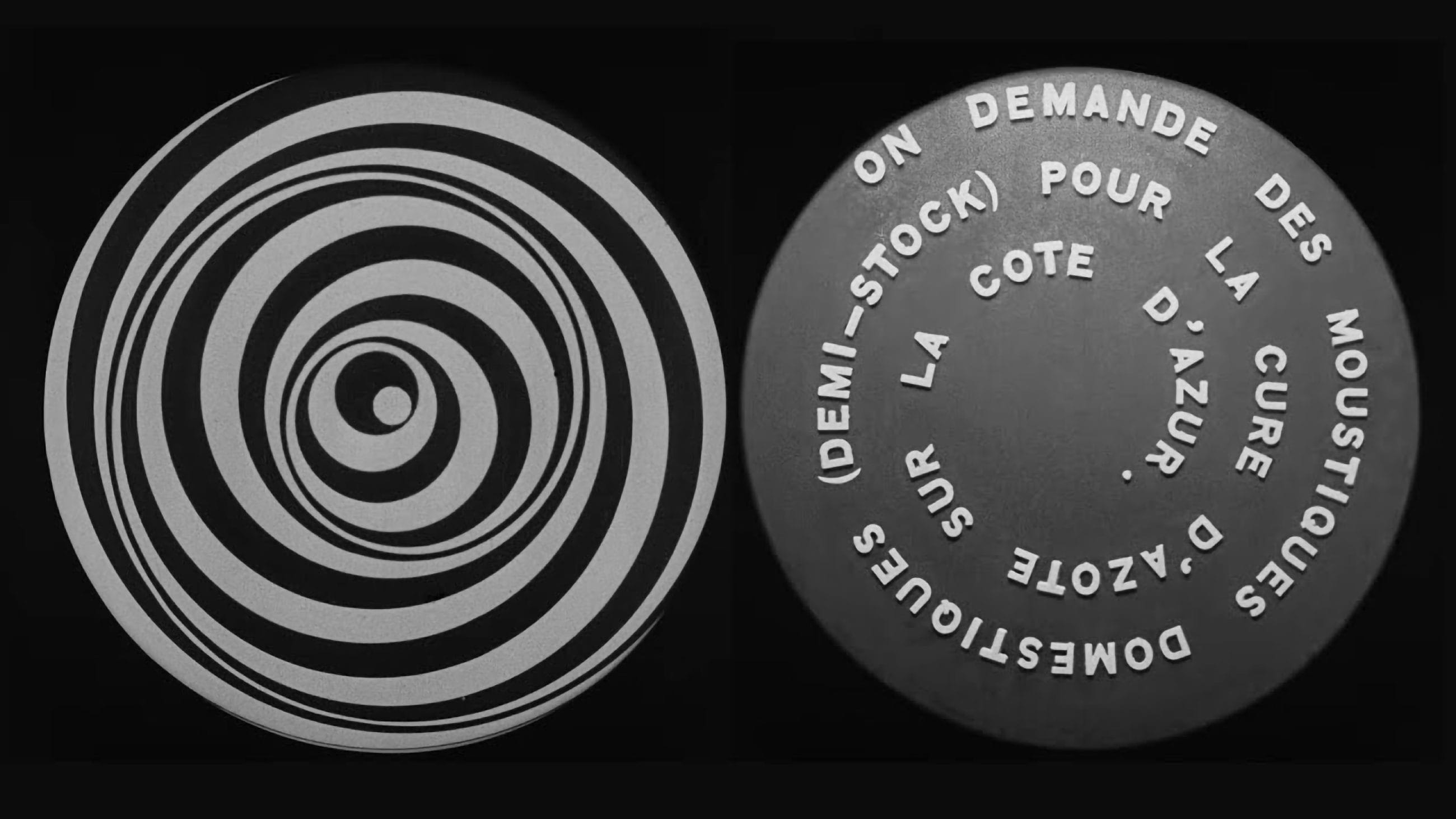

Consider for example Marcel Duchamp’s Anemic Cinema (1926). Here the movement of spirals and geometrical forms, accompanied by visual wordplay, creates a sequence of images that involving machines as main components of the work, which is a video (now converted in digital). Or think about László Moholy-Nagy’s photography series and his machine called Light Prop for an Electric Stage (1930), that he used to study light and choreographies also during his Bauhaus period. These are clear examples of the presence and use of technology in the process of creating in the first half of the 20th century.

During that period, also Constructivism used technology as a fundamental part of the production — for example in Tatlin’s Monument to the third international (1919-20) — but it was the Futurism, that generated the idea of technology as essential in art, but mostly in society and human body. In 1910, in fact, the founder of the movement, F.T. Marinetti, published the novel Mafarka Futurista (1910) in which he dreamed a future connection between human bodies and machines, believing in an irreversible fusion that would overcome and break ties with the past and culture. It would have been Andy Warhol, fifty years later to declare the final union anticipated and dreamed by Marinetti. In 1963 interview for ARTNews he stated: «I want to be a machine, and I feel that whatever I do and do machinelike is what I want to do» [1].

It was after the Second World War in fact, that the relationship between art and technology became increasingly strong and supported. In the 1960s, this connection was not only championed by artist but also through institutional exhibitions, critics and technology itself, all contributing to emergence of a new trend based on the use of technology in and as art.

In collaboration with the artist Robert Rauschenberg, engineer Billy Klüver founded the group Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.) to promote the fusion of art and technology. This initiative was rooted in their previous partnership on the 1966 project Oracle and was preceded by their extraordinary collaboration with Jean Tinguely between 1962 and 1965 on Homage to New York, a self-constructing and self-destructive artwork. In the meantime, major institutions like the MoMA or the Jewish Museum in New York, but also the Institute of Contemporary Art in London, hosted incredible exhibitions that promoted this dynamic fusion.

During the 1970s, a romantic feeling “anti-computer” [1] increased overwhelmingly against the use of technology in wars and control and surveillance policies. Even if during the entire decade until the 1990s the art world excluded the technology from its system, the presence of technology in artworks continued. In spite of this fact, artists like Nam June Paik — already known for his TV series like TV Buddha (1974) or TV Cello with Charlotte Moorman (1976) — or Dan Graham — with his rooms, like Time Delay Room in “ctrl_space” (1974), or the eighties pavilions — persisted in their research, focusing more on videos and installation. Their research merged the use of technology with the aesthetics of Minimal Art, Conceptual Art and Arte Povera, involving the audience inspired by Happenings and Fluxus, using the machine not just as a machine but as a more complex signifier and creator of signifiants.

The journey of what is now defined as New Media Art — and what it could potentially become — is perfectly described in the monumental research of Domenico Quaranta [1]. However, what’s important to note is that the cultural activism of the late 1960s and 1970s pushed this kind of art into a non-systematic niche. Festival like Ars Electronica (Linz, 1979) were born shaping another idea of art, completely separated from the institutional system. The collaboration between art and technology continued, but outside mainstream channels, and it was during the 1980s that there was a renewed interest in this type of art, finally restored during 1990s.

Among the many artists who could be mentioned at this stage of rediscovery during 1990s, I would like to recall Jenny Holzer, who began experimenting with combining video or LEDs with space earning a Golden Lion for Best Pavilion at the 1990 Venice Biennale, and Tony Oursler, a pioneer of the research which merge video and sculpture, like in his series of “talking heads” that took shape after a long process of research started in the 1980s. In 1994 — exactly the year of birth of the Net.Art — Antoni Muntadas presented to the public an installation of an interactive digital archive referred to specific cases of censorship and collective private spaces called The Room at the Chicago Cultural Center (US). Whereas other artists like Pipilotti Rist or Doug Aitken were trying to find immersive way to project their videos evolving the lesson of Bruce Nauman. Pipilotti Rist created Sip My Ocean (1996), a 2 channel video projected as two mirrored reflections on adjoining walls flowing sequence of dreamlike images, while Doug Aitken worked with translucent screens like in the installations Electric Earth (1999) and Interiors (2002). These are perfect examples of the LOWTECH ambitions to unify technologies and arts in one unique and expanded reality. A reality that would once again be split throughout and beyond the decade, major changes in the society and critics of the time.

In 1994 in fact, the Net.Art was born, and the dualism between systemic art and technological art turned into a dualism between a “Duchamp Land” (the physical space) and “Turing Land” (the virtual space) [1]. Beyond cables, computer e monitors — physical components for Quaranta [2] — the problem was the translation of digital art and concept into physical spaces, or at least knowing how to exhibit digital art without failing — like the exhibition Documenta X curated by Catherine David in 1997, where the decision to isolate Net.Art in a sponsor-branded room led to its trivialization and “ghettoization” [3]. Therefore, despite many museums and curators began a process of wise integration of the new trends, the critical juncture amplified the sense of distinction between the two worlds, to the extent that New Media Art became isolated in its festivals, and in many cases fueled the belief on the part of some artists in the complete separation of the two worlds, leading them to work exclusively online. For a long period of time, most net.artists worked exclusively online, such as Gazira Babeli, and the net itself started to produce new art formulas based on the premises of the 1990s. Nowadays, this division between the virtual and the physical world appears to be still present, to the point that from 2020 to 2021, the NFT media boom has brought the topic back into vogue, rediscovering this pointless dualism.

Fortunately from the late 2000s to the 2020s we witnessed the increase of a more opened conception of art that aimed to explore a broader concept of digital art, not defined just by its medium. This peculiar art was already conceived as post-media art or, quoting Nicolas Bourriaud, a Postproduction art, that specifically tents to create «a site of navigation, a portal, a generator of activities» [4] that would connect and blend virtual reality with physical space, fostering a new artistic language and expression. This portal would bring virtual conditions of a new distribution and fruition of art into physical reality, aligning precisely with the principles of LOWTECH.

Numerous artists tended to investigating the potential of the virtual world and technology in relationship with human beings and physical spaces, through technology’s devices and contemporary art displays. Two notable examples are Cory Arcangel and Eva & Franco Mattes, also known as 0100101110101101.org. Arcangel, who defined a new interaction between video games and installations, revealing the fragility of the machine and technological forms, like in Super Mario Clouds (2002), inviting viewers to reconsider the aesthetics and underlying structures of digital media. Whilst Eva & Franco Mattes constantly worked in this direction, conceiving a symbiosis between virtual and physical worlds, they aimed to translate a concept rather than a specific aesthetic through video installations. This approach culminated in BEFNOED (2013-), a series of videos recorded by anonymous gig workers performing absurd actions via webcam. These videos were later presented on multi-screens scattered throughout art spaces and placed high above or low to the ground, forcing spectators to crouch, stretch, or contort, thus turning them into participants and translating the online experience into a tangible, immersive encounter.

Another notable work is Personal Photographs (2019-), a series of installations showcasing the hidden infrastructures of data systems, such as metal conduits and cables, which are typically invisible behind the digital content we consume. The piece involves Raspberry Pi computers interconnected through a peer-to-peer network, circulating images from the artists’ personal archive in a loop. Presented in various forms, from small-scale framed works to large, immersive installations, the work challenges the focus on images by highlighting the tangible materiality of the technology that enables digital communication.

The LOWTECH tendency seems to take shape from all these previous research and historical flow, mixing the background of the past with the power of installation aesthetics by contemporary personalities who sinuously shaped paintings and installations suspended within virtual and physical. Although LOWTECH doesn’t intend to put a label on artists and practices, it’s clear that there are roots and references that need to be declared and noticed. Producing a digital painting today means producing a work grounded in pioneering experiments such as Wade Guyton’s Epson Ultrachrome HDX inkjet series, or Richard Prince’s paintings and screenshot series from 2014, or again like Seth Price’s 3D / 2D paintings. Exactly like digital paintings, today, video installations, installations and sculptures are deeply rooted in the practices of artists such as Cady Noland, Arman, Jason Dodge, Ryan Gander, Michael E.Smith and Claire Fontaine, that in the end are all debtors to the ready made provocation by Marcel Duchamp.

¹ What is LOWTECH?, Fakewhale, February 27, 2025 – https://log.fakewhale.xyz/what-is-lowtech/

² ibidem

³ G.R. Swenson, The Reason I’m Painting This Way is That I Want To Be a Machine… Andy Warhol, Art News, v.62, November 1963.

⁴ Taylor Grant, How Anti-Computer Sentiment Shaped Early Computer Art, Conferenza Refresh!, s.l., s.n., 2008 – http://95.216.75.113/handle/123456789/346.

⁵ Domenico Quaranta, Beyond New Media Art, Brescia, LINK Editions, 2013.

⁶ Lev Manovich, The Death of Computer Art, s.l., Rhizome, 1996 – https://rhizome.org/community/41703/.

⁷ Domenico Quaranta, It Isn’t Immaterial, Stupid! The Unbearable Materiality of the Digital, Artecontexto, II, 2009, pp. 35–41.

⁸ Domenico Quaranta, Beyond New Media Art, Brescia, LINK Editions, 2013.

⁹ Nicolas Bourriaud, Postproduction. Culture as Screenplay: How Art Reprograms the World, Lukas & Sternberg, New York, 2002.

Matteo Giovanelli

Matteo Giovanelli (Brescia, 1999) is an art historian, emergent curator, and writer with a versatile approach to contemporary art. Holding a BA in Cultural Heritage and an MA in Art History from the University of Verona, he has developed a versatile profile through his work at APALAZZOGALLERY, where he supported artists and contributed to the organization of exhibitions, international art fairs and curatorial projects, managing projects across all aspects of their realization. As a writer, Matteo collaborates with esteemed publications such as ARTFORUM and Flash Art, offering insightful critiques and analyses of contemporary artistic practices. he combines a keen eye for innovation with critical insight, offering thoughtful perspectives on the evolving art landscape.

You may also like

Breaking Walls, Building Worlds: In Conversation with Jakestudyos

Introducing Jakestudyos Artist: Jakestudyos – Living in: Manila, Philippines Visit Artist Webs

Ian Wilson: There Was a Discussion

There was a time when conceptual artists roamed the art world. But some were more so than others. Th

Fakewhale in Dialogue with Fabian Lehmann: Exploring the Intersection of Materials, Media, and Digital Duality

Fabian Lehmann’s work exists at the intersection of materiality and memory, where digital and anal