Fakewhale in dialogue with Tim Plamper

For some time, we have been following Tim Plamper’s work, fascinated by his ability to blend different artistic languages such as drawing, cinema, and performance to explore human psychology and the themes of identity, trauma, and myth. His works, especially the “Exit II” cycle, offer a dense fabric of symbolism and critique that delves into the depths of the unconscious and contemporary culture. At Fakewhale, we had the pleasure of speaking with him to understand better his creative process, the evolution of his research, and the meaning of his most recent works.

Fakewhale: You often describe your creative process as a ‘garden’ to cultivate, where ideas grow and influence each other, and sometimes need to be trimmed or resized. Could you tell us how a new work comes to life and develops? Does the idea arise from inspiration or something similar?

Tim Plamper: Yes, that is a metaphor I often use to describe my practice. It fits quite well because, to me, all individual pieces, or at least groups of artworks are interconnected on a certain level.

A work of art almost always emerges from a moment of genuine inspiration. One could say that this moment invariably occurs when I am moving about when I am in motion. There is a point when the idea suddenly takes shape in my mind and already begins to form quite comprehensively. This form could be considered the seed, which, if I deem it worthwhile, I plant in the garden and allow it the opportunity to grow further. Some seeds take shape quickly and develop into autonomous artworks, while others remain dormant underground for a long time. Some artworks evolve from the seeds of pre-existing works, growing almost independently. Yet, in certain areas, the garden grows rather wildly and must be kept in check. Here, I have to limit and cultivate the overgrowth.

The nature of the work also plays a significant role. Performances and films require much more effort. For those, I work extensively with scripts, creating exhaustive PDFs filled with text, sketches, and moods, and I establish a cohesive context for all these elements.

Which past and contemporary artists have most influenced your practice? How have these references shaped your approach to art and the development of your works?

Throughout my life, various artists have profoundly influenced me, often striking me with their work in a way that left me utterly defenseless. It would take a considerable amount of time to free myself from their spirit. This kind of encounter – or perhaps one should rather call it a collision – has always appealed to me. When an idea is so powerful that it threatens to overwhelm you, it can be challenging to learn how to navigate such an experience. But if one manages to appropriately integrate it into one’s own worldview, it becomes a deeply enriching gift.

Over the past decade, however, I have made a conscious effort to distance myself from external influences and the work of other artists, seeking inspiration instead within myself, my own life, my personal experiences, and my own reflections. Particularly since 2017/18, with the commencement of the “Exit II” cycle, I have found that inspiration arises naturally from within this body of work. There is so much that emerges organically, which I can accept as a gift. Here, I must be more discerning about what to select, which branches to pursue, which roots to protect, and which lines to follow.

Nevertheless, there have been significant moments of encounter with other artists throughout my artistic journey. I grew up with a book in my family home titled “German Painters of the Romantic Era”, but the most impactful discovery occurred in my high school library when, at the age of 16, I came across books containing Egon Schiele’s drawings. This was a true collision for me; these drawings, with their intensity and extraordinary erotic energy, completely overwhelmed me as a teenager and have left a lasting impression to this day. Additionally, The Doors had an almost equal influence on me, profoundly shaping my perception of artistic expression and intensity, much like Schiele. In my first year at the academy, I encountered the work of Neo Rauch. It took me a very long time to free myself from his grasp. During my studies, I also discovered Joy Division, who had a very significant impact on my work, too. Their raw, wild energy, which is utterly hopeless and dark, yet manages to convey profound poetry, resonated deeply with me. Marcel Duchamp has also been a recurrent influence, provoking much thought over the years. He represents, in his unique way, an artist who is not merely a creator of images but one who embodies an artistic-philosophical stance, which still resonates with me today. His approach to art, which is not solely focused on material production but is first and foremost an intellectual and spiritual endeavor, continues to shape my practice until today. Similarly, Andrei Tarkovsky’s films have had the most significant influence on my approach to art and my own work over the past decade. I found in him a kindred spirit who also descended deep into the human soul. He radically refuses to conform to the rational demands of his time, instead offering a profound spiritual vision rooted in personal experience, bringing with it an equally personal suffering and beauty. The same could be said of Joseph Beuys, whom I admire primarily as a draftsman, a thinker, a spiritual teacher, a public figure, and a political persona.

Your work “Exit II” unfolds across ten films and exhibitions. How did you decide to structure this project over such a long timeframe, and what challenges did you encounter in maintaining narrative and visual consistency across the various chapters?

This evolution was quite organic, I must say. I spent the winter of 2017/18 in Palermo, a period following my major solo exhibition “Zone” at Suzanne Tarasieve in Paris, where I had reached a point in my artistic journey that I had been striving for since completing my

studies. My focus was on developing large-scale drawings that, on one hand, appear highly realistic but, on closer inspection, remain strikingly abstract. This series, titled “Dissociations”, consisted of five large-format pieces and two additional drawings named “Zona” and “Europe After the Rain.”

At that juncture, I asked myself: What comes next? Should I continue creating more large scale drawings, or should I explore something entirely new? I was reluctant to fall into a repetitive cycle of production that would soon bore me. Thus, I decided to pursue a fresh direction. A theme had already begun to emerge in my last drawing from 2017, “Europe After the Rain,” which depicted two dark sewer shafts leading underground. I followed this call to the subterranean, contemplating how I could approach this metaphorical underworld, often depicted in mythology and psychology as the unconscious. Ultimately, I chose the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice as a starting point and developed a script based on it – a collection of notes, thoughts, and quotes loosely organized. This spontaneous structure allowed me to divide the work into ten chapters, each with its own title.

I continue to adhere to this structure, expanding it with each film. Every film features a voice-over of the text I wrote in 2017/18, along with a new script tailored to the film’s themes and scenes, serving as a prelude to the original script. This new material, like the initial draft, retains a raw and unpolished form.

Each film stands as an independent artwork, accompanied by an encompassing exhibition. These exhibitions include objects and drawings created during the research phase or the process of scriptwriting, such as annotated script pages, inspiring objects, film-related items, and costumes. Despite the films’ individuality, they all contribute to a larger whole, forming the “Exit II” cycle, which I envision as a living entity that evolves organically over time. Every new addition has its character and nature, influencing the existing parts, yet all elements collectively point toward the future.

From the outset, I was determined to open this project to external influences. This means inviting artists, musicians, actors, and performers to collaborate and contribute, allowing them as much creative freedom as possible. It is important to me that my collaborators have the space to express their distinct voices within this framework. Narrative coherence is primarily drawn from the 2017/18 script, which, even in its preliminary form, encompassed all ten films and their narratives. There is a common thread that runs through all the parts, traceable back to the project’s inception. Visual coherence, on the other hand, is maintained through a consistent structure I use to visualize keywords from the voice-over at critical moments in the films, much like subtitles positioned centrally over the footage. This technical approach creates a recognizable thread throughout the cycle, ensuring visual continuity. Thus, the entire series is held together by an internal coherence rooted in the script and an external one determined by the technical format.

In your large-format drawings, you use a unique approach that goes beyond classical perspective, expanding the depth of the image into a temporal and mental dimension. How did you come to develop this technique, and what do you aim to communicate through these visual layers?

This approach emerged from a series of drawings titled “Atlas”, which was inspired by a particular incident. In 2014, I took a train journey from Berlin to Georgia in the Caucasus to see Mount Kazbek, where, according to mythology, Prometheus was chained. During this trip, I filmed and photographed extensively, capturing landscapes, rivers at night, and moments of transit. While I stayed in Istanbul for a few days, I needed to send one of these recordings for an upcoming solo exhibition. Unfortunately, in the internet café where I tried to send the file, my SD card malfunctioned, and all the visual material I had gathered up to that point was lost. Back in Berlin, I attempted to recover the files with specialized software, but to no avail. Apart from a few small sound fragments that remained on the card, everything was gone.

Convinced of the significance of the scenes I believed I had captured, I found no peace and decided to work with these last remnants of the lost recordings. I secluded myself in my studio for a week and created an entire album titled “Europa” While working on this album with various sound programs, my attention kept returning to the sound spectrum, the visual representation of the audio.

It dawned on me that this soundscape precisely depicted what I had hoped to document on my journey – a dark, blurred, reflective landscape. I then began extracting small fragments from this soundscape and translating them into large-scale drawings. For the first time, I layered these visual representations of sound fragments with other images I had taken during my travels, creating a hybrid form where my memory merged with the documented.

What has always fascinated me about music is its profound emotional depth – the way it can touch a listener’s soul. Visual art, in comparison, rarely reaches such intensity. Yet, through this method of translating sound into image, I found a way to capture and convey this depth in my drawings.

This process led to a unique compositional style, reminiscent of double exposures in traditional photography, while also bearing similarities to sculptural techniques and cinematic structures. However, unlike in film, where narrative emerges from a sequence of images, my narrative unfolds in the depth of the images themselves. I work within the confines of the physical space of the paper, which, though merely a few tenths of a millimeter deep, extends into a profound mental dimension.

For me, this approach is incredibly compelling because it allows me to create a landscape that invites the viewer to enter. It is crucial that these drawings are large in scale, a principle I have maintained to this day. The format exceeds the dimensions of the human body, engaging the viewer’s physical and mental presence. It is a space that one can enter with both the body and the mind.

I deliberately avoid classical means of perspective or illusionistic depictions of space, instead drawing inspiration from the structure of dreamscapes, which exist fully formed from the outset, through which the dreamer moves. These dream spaces exhibit strange, otherworldly structures, vastly different from those of the waking world. In dreams, things are connected more by association than by causality; different laws prevail – the ‘Laws of Soul’.

You often explore the collective unconscious in your works, as described by Jung. How do you believe myths and dreams can reveal something universal about the human experience, and how does this relate to the current context?

During my studies, I found my way to Jung’s writings through alchemical imagery, a subject to which he was deeply devoted. Since then, I have been profoundly inspired by his theory of archetypes, exploring it at various points in my artistic practice. Ultimately, I

view Jung’s psychological theories, along with myths and dreams, as frameworks for understanding the world. They are human constructs that can help us make sense of our surroundings and find our place within them.

I believe that all forms of human endeavor – be it in religion, art, or science – serve as tools to orient us in the world. Through these means, we create stories, images, maps, and theories that help us navigate our reality. This issue is particularly pressing today, given the political developments of recent decades, both globally and within Europe. We are once again confronted with questions of origin, belonging, and orientation. Our societies are currently searching for new directions in which to evolve. We need visions for how we can shape our world. At the same time, we face challenges of xenophobia, the exclusion of the ‘Other’, and a general fear of the unknown. In such times, it is worthwhile to revisit myths and seek alternative narratives that transcend the current situation. It seems to me that Europe has lost the unifying vision that flourished so vividly in the 1990s. We lack a cohesive force that unites us as European culture and provides a shared sense of direction for building a positive future together. A look at our cultural heritage and into the depths of our souls could be very helpful in this search.

Memory is a recurring theme in your work, and you’ve spoken about its fluid and inconsistent nature. How does this concept of memory reflect in the process of creating and experiencing your artworks?

I would say that memory is, first and foremost, a story we tell ourselves. It is an active process, a deliberate act we engage in individually, yet it also serves as a collective activity through which we connect with others. Thus, remembering carries a responsibility, both personal and shared. Memory is never static; it is a dynamic, ever-evolving process of shaping and adapting, a vital aspect of our lives.

This concept closely parallels the artistic creation process, which is also highly active and entails a sense of responsibility. Artists are accountable for their actions and creative expressions. The same holds true for the experience and appreciation of art. Engaging with and immersing oneself in a work of art is a form of communication. In my view, participation in art is an active endeavor because only through interaction with the audience – those who engage with the artwork – does the art truly come alive. This process of participation and shared experience of art is particularly significant to me. Art, especially in the context of social interaction, fosters a sense of community and shared responsibility. It is within this space that a collective narrative can emerge, and culture is created.

In the “Exit II” cycle, you focus on the concept of the underworld in relation both to the human psyche and the current political situation. What led you to choose the myth of Orpheus as the main narrative structure for exploring these universal themes?

When I decided to explore the concept of the underworld, I chose to primarily focus on the perspective of ancient Greece. It soon became evident that this classical notion of the underworld shared many similarities with the concept of the unconscious mind, making it worthwhile to compare and intertwine these two ideas. The juxtaposition of these distinct worldviews proved to be highly fruitful. I began to question what parallels could be drawn between the figures emerging from both realms and how the structures of the unconscious are reflected in Orpheus’s journey into the underworld, and vice versa. This exploration was immensely captivating, especially as I started to search for modern equivalents of these figures and stages, casting them in a new light against the backdrop of these two perspectives.

I chose the myth, particularly the story of Eurydice, because Orpheus, in this narrative, is fundamentally an artist attempting to rescue his beloved through the power of his art. At the same time, he embodies a shaman-like figure who ventures into darkness, into the unknown. His descent into the underworld is a tale of loss and tragedy that remains unresolved from beginning to end. There is no redemption for the lovers; Orpheus fails due to his inability to resist temptation and is ultimately torn apart by the Maenads. I found it particularly intriguing how the story abruptly ends at this point, like a cliff dropping off into the ocean, only for him to be unexpectedly elevated to the heavens as a constellation. This story of loss, pain, crossing boundaries, darkness, and despair seemed a fitting metaphor for our current political and social climate, which, at least in my perception, had already begun to reveal itself in 2017. It evokes a sense of standing at the end of an era, perhaps even an age, tasting the sorrow that is yet to come. Unfortunately, this premonition has been increasingly validated by the ongoing political developments, including wars in Europe and Palestine, and the global pandemic. The latter played a significant role in my second film of the cycle which is titled “Exit II (The Beloved Dies)”, echoing themes of losing loved ones, the disappearance of the familiar, and the longing for what has been lost.

Yet, the myth also speaks of the courage to descend into darkness, to confront the unknown and one’s own shadow, and to bring, if only briefly, a light into that darkness. It is therefore is, to me, a perfect example of how humanity opposes the transience of existence with its vital creations, thereby imbuing life with a deeper cultural significance.

The notion of ‘symbolic sediment’ is central to your work. Could you elaborate on how the symbols and traces you leave in your pieces function as mirrors of your thought process and how they invite the viewer to actively participate?

This question relates to two pivotal aspects of my artistic practice in recent years. First, the symbolic realm has taken on an increasingly significant role in my work, particularly through my engagement with the “Exit II” cycle. I came to realize that symbols, in their most profound and elevated sense, act as ‘keys’ to unlocking the irrational structures of our being. As I explored this realm of the irrational, delving into themes of the underworld, identity, and origin, I discovered that symbols are among the most powerful cognitive tools available to the human mind. They can partially unveil potential answers and open pathways that transcend rational and causal thought, shedding light on a kind of universal substructure.

Secondly, I realized that the concept of sediment also plays a fundamental role in my artistic approach. After my exhibition “Zone” at Suzanne Tarasieve in 2017 in Paris, I decided to take a new direction and confront my own abyss. I closed my eyes and began creating blind drawings, ultimately producing over 1,000 A4 drawings. This raised the question of how to handle such a vast quantity of drawings – whether to select and categorize them, destroy those I deemed unsuccessful, or find another way of engaging with them. This process reminded me of a moment from my youth when I discovered that my parents had discarded most of my childhood drawings, which were now lost. I collected whatever I could find and archived these A4 drawings in a binder with plastic sleeves. From that point on, I continued this practice until the beginning of my studies, ultimately amassing nearly a meter of binders filled with drawings. These collections, organized chronologically, formed a visual diary spanning almost a decade of my life. In 2018, I revisited this method, organizing the blind drawings into binders once again. The drawings I considered unsuccessful were placed on a separate pile, which gradually took on greater significance as I realized that these rejected works often pointed towards something unknown. Starting from this pile of discarded drawings, I liberated the other drawings from their binders and arranged them in similar stacks. During the subsequent year-long process, with these drawing blocks lying on my tables, I increasingly felt that the block format was particularly fitting. These blocks compress both content and time, creating a kind of ‘sediment of meaning’.

Similar to my large-scale drawings, these blocks feature a layering of images and contain both temporal and mental depth stored within them. Based on these experiences, I continued this approach in subsequent projects. All sketches created during the preparations for my performances and films, as well as other projects outside the film cycle, were developed in A4 format and preserved in similar sediment blocks. I took this approach even further by including all sorts of material – receipts, correspondence, letters, and found objects related to the projects – thus opening my artistic practice even more to external influences and chance occurrences. These new blocks have become true repositories, gathering diverse materials that communicate and relate to one another, creating a raw, cohesive whole.

In your performance “Security III (Tiger)”, you explore themes of power, violence, and control. How do you use the body and the temporal duration of the performance to address these concepts, and how do these ideas interact with your visual work?

The performances are rooted in two significant experiences I’ve had since 2018. First, there are the insights gained from drawing with closed eyes. In the absence of sight as the guiding sense, the awareness of the body takes on a much more significant role. The body, in this context, is no longer merely a tool of the mind but becomes the subject of expression. When drawing with closed eyes, one must listen closely to the body, and at a certain point, body and mind begin to oscillate in harmony, moving together on the medium of paper.

The second experience came in the summer of 2018 when I traveled to Greece to visit one of the sites believed by the ancient Greeks to be an entrance to the underworld. Upon arriving at the cave, known as the “Oracle of Hypnos”, I began photographing, moving through, and exploring the space. It quickly became clear to me that this place had something specific in store for me. I resisted this intuition for several hours, wandering around in near embarrassment. Only after taking a swim in the nearby sea did I finally decide to surrender to the call of this magical place. I returned to the cave, undressed, set up my camera with a self-timer on the ruins, and submitted myself to the environment. I repeated this ritual every morning for the next four days, returning to the cave, disrobing, and connecting with the soil – a very clay-like, tactile soil, highly malleable. It was as if I were making love to the earth, yielding to the entrance of the land and allowing myself to be absorbed by it. In retrospect, I realized that this was my first performance. This was an intense and profound, yet also unsettling experience that had a significant impact on me. I brought this performative, embodied approach back to my studio and sought to translate it into new forms, engaging physically with other concepts. The first of these was the concept of ‘Security’, which I explored in the studio through performance. This time, though still not public, I involved a photographer, which expanded upon the initial experience. Naked but wearing a security jacket, I performed around and over the blind drawings I had created up to that point. This process proved to be extremely fertile and inspiring for all subsequent work. I have continued to develop and refine this approach ever since.

I view this as the essential quality of performance art: the holistic engagement of body and mind with concepts, negotiating them, and communicating them to others. It is a way of artistically processing ideas, presenting them, and provoking a response in the audience, entering into a dialogue on both an intellectual and physical level.

The experiences I had with blind drawing, where the body suddenly assumed a much greater significance in understanding and feeling, also informed my understanding of performance. There are parallels here with my large-scale drawings, which similarly aim to captivate the viewer on both a physical and mental level.

In many of your recent works, such as “Aura” and “Lovers,” drawing plays a prominent role. How do you see the evolution of drawing as a medium in your practice, and how does it intertwine with your exploration of other art forms such as performance and cinema?

Drawing is undoubtedly the core of my artistic practice, but as I have already hinted, it is intrinsically and deeply interconnected with all other forms of expression in my work, enriching and complementing one another. In my large-scale drawings, similar elements come into play as they do in my performances. For me, the process of creating a large scale drawing is at least as important as the finished image itself. Some drawings take months to complete, and this process mirrors the experience of a performance. Both can be described as a journey – an expedition into a foreign landscape to explore new experiences. In both cases, my fascination with dream imagery and visions plays a significant role.

In front of a developing drawing, which I see as a gateway to another visual world (Bildwelt), I ‘perform’ with the pencil on the paper, engaging not only my hands but my entire body and mind, embarking on this journey. Music is crucial here. The most productive moments in drawing occur when I find myself in a trance-like state – moments where I completely lose myself, becoming one with the act of drawing, guided by my intuition and in sync with the rhythm of my drawing, dancing body, and the music. In these instances, I forget myself, and everything unfolds in a state of complete flow, sometimes lasting up to twelve hours. This state closely resembles that of performance, with many parallels between them.

The concept of the “hyper-surface” emerges strongly in your “Atlas” series. How does this notion of the virtual extension of the surface relate to how you perceive space and time in your works?

Since 2015, with the series “Atlas”, a discernible evolution in my artistic practice can be observed, particularly in the way my large-scale drawings engage with the concept of expanding the (virtual) depth of the image beyond the picture plane. My intention is not to extend the classical perspective, which projects the three dimensions of space onto the two-dimensional surface, but rather to virtually introduce a third dimension of depth that can best be described as ‘temporal’ or ‘mental’ in nature, unfolding vertically towards the viewer. To clarify: through the layering, superimposition, and blending of multiple images and diverse content on a single surface, I create an image space that resembles a vivid screen during a film screening – except that the entirety of the film, or all its scenes, are visible simultaneously. This process forms a spatial sediment of the temporal dimension. The concept of the ‘hyper-surface’ in my “Atlas” series thus represents a virtual expansion of the image surface, transcending traditional notions of spatial and temporal boundaries. In my work, I view the surface not merely as a two-dimensional field, but as a multidimensional space where various elements interact and merge. This expanded surface becomes a threshold space, a portal that enables the exploration of different temporalities and dimensions, much like a palimpsest where layers of meaning are inscribed, erased, and rewritten.

In the “Atlas” series, the drawings are not confined to their immediate physical presence but suggest a depth that resonates with the performative and cinematic aspects of my practice. Each stroke, each line, is a trace of a journey, a gesture that extends beyond the paper into a conceptual space that I traverse with my entire body and mind. This methodology allows me to explore the fluid interplay between the tangible and the intangible, the visible and the invisible – between the picture and the image, much like a hyperlink oscillates between different layers of content.

The ‘hyper-surface’ thus becomes a dynamic field where time is experienced not linearly, but as a series of overlapping moments – states of trance, flow, and deep immersion. These drawings, created over several months, embody a temporal depth in which the traces of my performances are captured on the image. Ultimately, the ‘hyper-surface’ in my work serves as a conceptual tool that unites the various forms of expression within my practice, creating a continuum of mind and body. It forms a cohesive and multilayered narrative landscape, inviting the viewer to engage with it both physically and mentally.

”Exit II” is not just a personal work but also aims to create a space for dialogue between different cultures and identities. What is your vision of the role of art in building a common European identity, especially in times of political and social crisis?

”Exit II” aims to create a dialogue between different cultures and identities by exploring the psychological and symbolic dimensions of the underworld in the context of contemporary political and social crises. My vision of the role of art in building a common European identity is deeply rooted in the ability of art to transcend national boundaries and offer a shared space for reflection and connection. Art can provide a platform for engaging with complex questions about identity, origins, and the self, while also addressing the fears and uncertainties that shape our societies.

In times of political and social crisis, such as those we are currently experiencing in Europe and beyond, art has the potential to go beyond immediate crisis management. It can foster long-term visions that inspire faith, resilience, and a sense of shared purpose. By confronting themes of violence, loss, and trauma, but also love and renewal, “Exit II” seeks to contribute to the collective processing of these experiences and to illuminate the underlying symbolic structures that connect us all. This process can help build a common cultural framework that acknowledges our diverse backgrounds while uniting us in the pursuit of a shared future.

Through collaborative artistic practice and the inclusion of voices from different countries and backgrounds, “Exit II” embodies the idea of Europe as a living, evolving cultural landscape. It invites participants and viewers to engage with the complex, often painful process of redefining identity in the face of change. By doing so, it exemplifies how art can serve as a tool for cultural integration, offering a vision of a European identity that is not fixed but constantly being reimagined and renegotiated in response to the challenges of our time.

Art, in this context, becomes a means of navigating the irrational and the unknown, offering a space where we can collectively explore new narratives and ways of being. “Exit II” serves as a testament to the power of artistic expression to foster dialogue, understanding, and ultimately, a more cohesive and resilient European identity.

How do you envision the cultural and political future of the European continent, and what role can art play in this historical moment?

In this context, art plays a crucial role, offering more than just a rationalistic worldview or immediate crisis management. It can create long-term visions that instill confidence in individuals and societies, guiding us through dark times, fostering belief, connecting us, and filling us with hope for who we want to be and how we wish to act.

What are your thoughts on artificial intelligence applied to art? (And by this, we mean in its various uses.)

I observe this development with great interest, as I have been using artificial intelligence tools as one of several means in my image production for years already. The rapid advancements in AI technology over the past few years have been truly remarkable, and it will be fascinating to see where this journey leads. Just yesterday, I had a conversation with my friend Michael Short, an art dealer from New York, about this very topic. We discussed the specific implications of AI-generated imagery. AI, after all, draws upon countless images found on the internet, reassembling fragments to create new compositions. These images are then redistributed online, becoming new material for future AI processes. This led me to wonder: could this result in a feedback loop? A situation where the signal is reiterated to the point of becoming incomprehensible. If we follow this line of thought, it suggests a development toward a kind of blurring or even an over-saturation of expression. While this could pose certain challenges, I am, as an artist rather than a technician, genuinely curious about the outcomes this phenomenon might produce.

In general, I believe that, much like other technological advancements throughout cultural history, AI is a tool that artists will undoubtedly incorporate into their practices. Just as artists have adapted to and utilized photography and film, they will also find ways to creatively engage with the capabilities of artificial intelligence.

What is particularly intriguing and challenging about artificial intelligence, however, is that it not only serves as a medium but also functions in a way as an author. This introduces a novel element to the discourse, as it raises new questions about authorship and copyright, in addition to the usual aesthetic considerations.

What role does emptiness play both in your creative process and in the reflections that your works provoke in the viewer?

The concept of emptiness, especially as a space for potential, holds a significant place in my art. In my large-scale drawings, I have always conceived of the figures as such vacant spaces. These are the areas on the paper with the least amount of graphite, creating a kind of opening – a void within the image that invites the viewer to project themselves into it. This void offers an entry point for the observer to fill with their presence, emotions, and experiences. This aspect is crucial to me because I believe that art should not convey a single, definitive meaning, but rather foster communication and collaboration. It is the viewer who completes the transaction.

But the empty spaces are not only vital within a single artwork, but also in the spaces between individual pieces – the virtual space in between, so to speak. I often work in series, where a thread of continuity is woven through repetitions, but there are deliberate gaps where it feels as though something is missing. I intend these voids to prompt viewers to engage, to fill these empty spaces with their own experiences.

Emptiness also plays a crucial role in my artistic process. It is essential to withdraw, to clear oneself, and to open up to new possibilities. This involves a kind of emptying of preconceptions to make room for something deeper to emerge. In critical moments, I consciously follow my intuition, allowing chance to play a significant role. On the other hand, I believe there are structures within our personalities that extend beyond conscious thought. By clearing my mind, I create a space for the unconscious to enter and actively participate in shaping the creative process.

In your works, references to classical culture and mythology blend with elements of contemporary culture such as capitalism and surveillance. How do you balance these seemingly distant worlds, and what do you hope will emerge from this encounter?

In 2017, when I decided to consciously draw upon one of these mythological narratives and began contemplating the parallels we might find between mythological figures and structures and our contemporary world, it quickly became evident that this juxtaposition was incredibly fertile ground. Modern equivalents for mythological concepts emerged readily, and this fusion of mythical imagery with contemporary elements created a captivating blend. I realized that myth is not merely a historical construct, but something 13

that can still be lived and experienced anew today. Even capitalism, for example, is deeply rooted in belief systems that can be traced back to Protestant worldviews – the belief in an afterlife, and in the notion of progress, an idea that remains present, albeit weakened, in our society – a belief in another world, a transcendental realm. Similarly, in our ‘insurance culture’, ‘security culture’, and ‘surveillance culture’, belief systems play a significant role. One might even ask: Is this surveillance apparatus not somewhat akin to the eyes of the gods? Gods who look down upon us, monitor our actions and serve as a moral authority hovering above us.

An interesting anecdote comes to mind: while working on my performance “Security IV (Event Horizon)”, I engaged deeply with Penrose diagrams, which I find visually appealing as well as conceptually elegant in their simplicity. A Penrose diagram is essentially a mathematical map of our universe. During my research, I also came across a diagram by C.G. Jung, which he drew to represent his unconscious mind. When I placed both diagrams side by side on my desk, I noticed their striking resemblance – they share a similar geometric structure, organize conceptual space in analogous ways, and, despite differing terminology, operate with similar dualities. When these two worldviews are overlaid, they reveal a surprising congruence.

This led me to question: what is the underlying essence of these two, or, more broadly, of all worldviews? What do these diagrams truly represent? Ultimately, I believe that these worldviews are not so much representations of the external world as they are maps of our inner selves, reflecting the external world within us.

Looking to the future, on what themes or artistic techniques do you think you will focus in your upcoming works, and in what direction do you see your artistic practice evolving?

I am currently working on a major solo exhibition featuring a new series of large-scale drawings, and I am also planning another series for the coming years. Simultaneously, I am preparing for a new performance and writing the script for my fourth film, which will be titled “Exit II (An den Grenzen)”.

fakewhale

Founded in 2021, Fakewhale advocates the digital art market's evolution. Viewing NFT technology as a container for art, and leveraging the expansive scope of digital culture, Fakewhale strives to shape a new ecosystem in which art and technology become the starting point, rather than the final destination.

You may also like

Cemile Sahin, «BB – BORN TO BLOOM», at Kunst Halle Sankt Gallen, St.Gallen

«BB – BORN TO BLOOM» by Cemile Sahin, curated by Giovanni Carmine, at Kunst Halle Sankt Gallen,

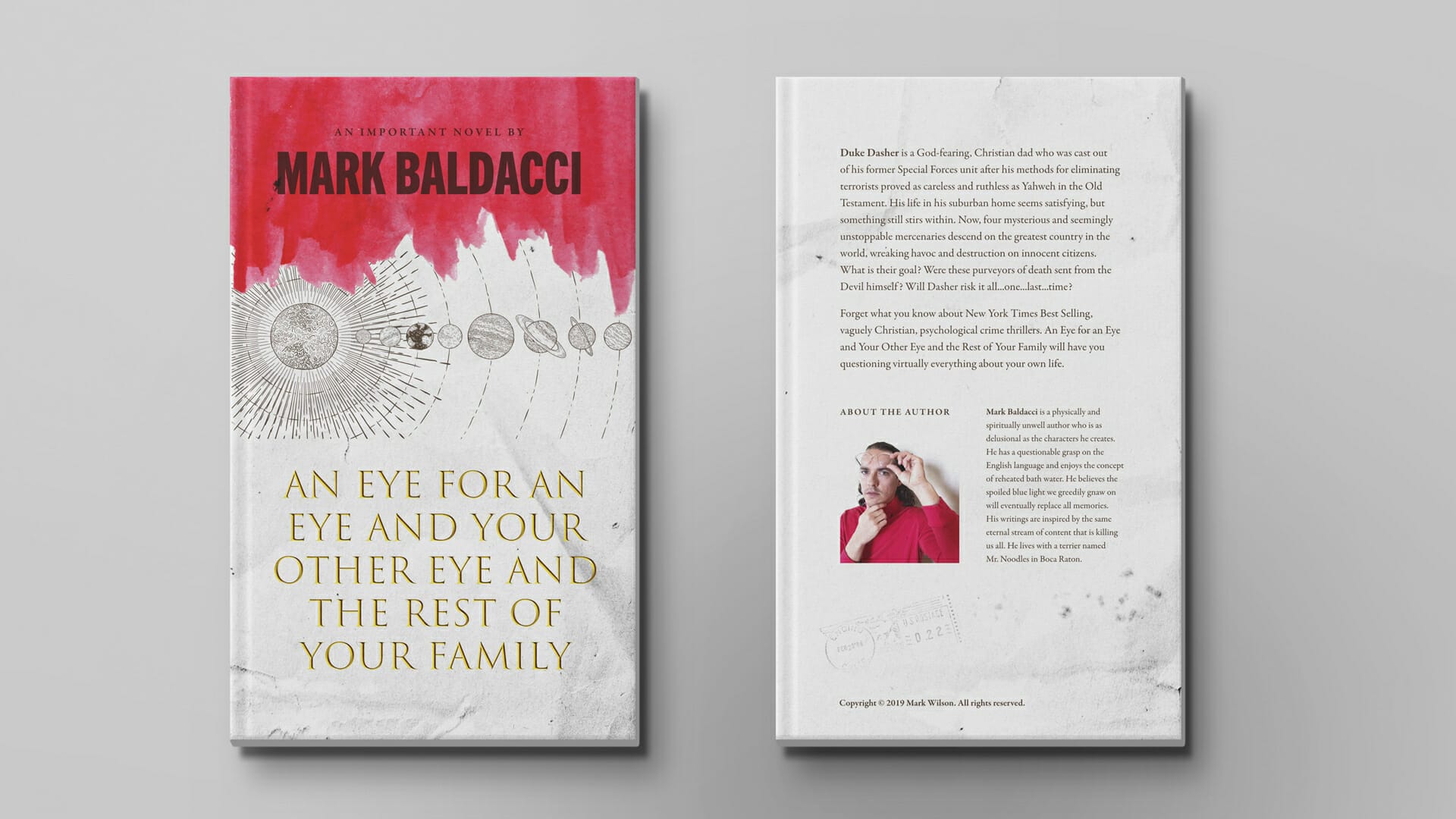

An Eye for an Eye and Your Other Eye and the Rest of Your Family

An Eye for an Eye and Your Other Eye and the Rest of Your Family was written and self-published und

Alexander Klaubert, Francis Kussatz, Julia Lübbecke, Rahel grote Lambers, Weaving Back to Common Grounds at ACUD Galerie, Berlin.

Weaving Back to Common Grounds by Alexander Klaubert, Francis Kussatz, Julia Lübbecke, and Rahel gr