Fakewhale in dialogue with Norma Jeane

Recently, we engaged in an ongoing dialogue with Norma Jeane and found ourselves captivated by the intricate relationship between identity, art, and the process of deconstruction and reconstruction that permeates her work. After several months of conversation, we have distilled and published some key questions here. Starting from the use of ‘Norma Jeane’ as a collective subject, and moving through reflections on consumer society and fragmented identity, we encounter an artistic practice that challenges the traditional notion of the artist as an isolated genius. In this interview, we delve into the intersections of collectivity, audience, and technology, seeking to better understand the creative tensions and possibilities that arise when these dynamics are questioned.

De-construction and Re-construction of Identity: How does Norma’s work relate to this?

To assign a name means to bring a subject out from an indistinct whole, in other words, to identify it. In the case of Norma Jeane, the name is not given to a person (after all, most of us already have one) but to a method of artistic creation with well-defined characteristics. To include a first hint that would allow one to grasp the character of this new subject starting from the name, a rhetorical figure has been used: antonomasia. This consists of attributing characteristics that can be adapted and extended to other subjects by using the proper name of a specific individual, due to the qualities recognized in them. The individual in question is Norma Jeane Baker, better known by her stage name Marilyn Monroe.

In her universal fame, Marilyn represents the distillation of pop culture and has become its main icon, thanks to Andy Warhol’s appropriation of her image. A symbol of superficial and artificial beauty, Marilyn generates an unshakable allure, completely impermeable to the context or the various situations staged by screenwriters. An abstract entity, a pure representation of the feminine ideal (in the masculine imagination of that era), in total opposition to Norma, the real person to whom that name was given for commercial communication purposes. Unlike her celluloid alter ego, Norma had a tormented and complex life. In this sense, the duality she embodied is emblematic of consumer society, where every entity is dressed by marketing in a celebratory costume, transforming every attempt to resist necessity into the idea of fulfilling a desire (often abstract, symbolic, and induced).

Norma Jeane as an artistic practice, therefore, is an attempt to escape the symbolic representation of an induced desire (the artwork as a symbolic object to be collected and traded) that is incorporated into a special person, whose uniqueness is certified by their biographical identity (the artist as the exception that proves the rule – “I am me, and you are nothing,” to quote Mario Monicelli’s *Il Marchese del Grillo*). Norma is a collective subject embodied by the people collaborating on each project. The artwork is not the result of a biography or a single personality, but rather of the creative process that arises from engaging with the complex and contradictory elements of reality.

Thank you for your analysis on Norma. It’s an excellent introduction and helpful for getting started. I find the dualism between Norma’s real identity and her iconic counterpart, Marilyn, particularly interesting. Norma Jeane’s artistic practice, as a “collective subject,” seems to challenge the traditional idea of the artist as a singular genius, a notion to which much of the art world is accustomed. How do you think this collective approach could radically redefine the concept of the artwork as we know it? Are you redesigning this concept? Or deconstructing it?

In a sense, yes, deconstructing to understand, and then redesigning to create different works, starting from the very foundations on which their raison d’être is built. The two pillars of a work of art are typically the exceptionality of its creator (which generates an aura of magic and symbolic predestination around both what they produce and their persona) and the ability of the work to represent concerns considered emblematic of the context in which it is conceived and realized (this second pillar is typically recognized retrospectively, in a historical perspective). These characteristics allow artists and their works to be used as symbolic representations of each historical phase, serving as the premise and necessary condition for its evolution into subsequent stages. In a way, this is a process of synthesis to the extreme, as if spotlights were turned on the tumultuous and difficult-to-comprehend evolutionary process, highlighting significant elements that allow for a simplified narrative. A representation of reality that is less unsettling and (seemingly) easier to grasp. Any gaps in this chain of meaning are then justifiable by the artist’s elusive genius. Convenient. And functional.

Norma’s work, on the other hand, acknowledges the limits of usefulness, does not aim for synthesis, and is based on the acceptance of limits (especially its own) as a starting point for exploration into new territories of meaning. The artist, therefore, becomes a dialectical counterpoint to utilitarian and rationalist synthesis, and the work itself becomes a talisman of complexity. Magical because it can never be fully expressed in other terms, and not translatable except through the existential experience of making or enjoying it.

This vision of artistic practice as an exploration of both personal and collective limits opens up new reflections on the very essence of art. I’m particularly intrigued by how this approach might influence the reception of the work by the audience. Do you believe that the audience’s involvement in the understanding and interpretation of the work can further enrich this process of “deconstruction and reconstruction” of artistic identity? Could you share one of your recent works where this occurred?Moreover, how do you think this approach might impact the social role of art, in terms of its ability to generate dialogue, empathy, or even collective action?

The involvement of the audience is always an existential condition for any work of art. A work is conceived as a collection of elements (more or less cohesive) that responds to a need for connection. Even if a work is created without the intention of being shown, it remains a tool for the artist to engage in dialogue with themselves. Thus, it is not the audience’s involvement (which is inevitable) that enriches the definition of artistic identity, but rather the artist’s awareness in conceiving and realizing the work.

As for myself, I have completely reversed the perspective and now observe my creative process as someone who feels like part of the audience. The relationship precedes and transcends the importance of expression. For example, in the work “Self” (http://www.normajeane-contemporary.com/index.php/portfolios/self20222023/), created for the Noor Light Festival in Riyadh, after considering the sophisticated role of technology (as a *deus ex machina*) in the works before and after mine in the exhibition path (by Aaron Mirza and Refik Anadol), I decided to work with a few simple technical elements to highlight the role of technique itself, beyond its effectiveness in producing highly suggestive effects (remaining inevitably in the background).

Regarding the social role of art, this approach fosters the potential for art to generate dialogue, empathy, and collective action. By removing the focus from the artist’s expression and placing it on the relationships and processes involved, art becomes a shared experience that invites reflection and interaction. It shifts from being a static object of contemplation to an active tool for engaging with complex realities, encouraging audiences not just to interpret but to participate. In this way, art can serve as a platform for collective inquiry, fostering deeper connections and potentially inspiring real-world action.

To this end, I created a system of devices for the nightclub (sound, lights, smoke, lasers, various effects) that operate solely on their own, throwing a party only in the absence of an audience. Every time someone peeks in to enter the dedicated space — curious to see what’s going on, where the music and lights are coming from — thanks to simple motion sensors, everything stops, plunging into silence and darkness. So, there’s little to nothing for the audience on a visual and sensory level, but a strong emotional response emerges, leading to uncertainty, questions, and liberating laughter.

Dialogue and empathy, and therefore the potential for collective action, depend on the sharing of experience in all its facets. The framing of a work establishes a reference point that facilitates a shared interpretation of the experience, thereby creating a new network of relationships, even among people who have never interacted before. But this is not exclusive to visual art. Cinema, music, literature — even memes — serve the same identity-forming function for both individuals and the communities they belong to. This applies even more so to creators and artists.

The point becomes quite interesting, and I wonder: how do you balance the desire to provoke a specific emotional experience in your audience with being open to their personal and unexpected interpretations? In other words, how much do you allow your message to be shaped by the audience’s reactions versus guiding those reactions yourself?

In reality, the work is largely open — actually, entirely open. The attempt to guide the relationship with the audience happens mostly in defining the framework. However, even this planning phase is full of variables tied to all the relationships essential to its development: with the production team, with the institution’s representatives (museum, gallery, biennial), and with the region where the institution is located. The approach changes a bit when a performative piece is restaged. In that case, the audience’s previous reactions are certainly taken into account. But in general, it’s an opportunity to introduce new variables that make it less predictable and more interesting, even for those who worked on it. Otherwise, where’s the fun?

How do you see your role as an artist in the digital age, where the audience is broader and more diverse, and works are open to endless interpretations and re-appropriations through social media and other digital platforms?

Quite comfortably. Since I don’t have any pre-established truths or the need for self-representation, any reinterpretation or appropriation is welcome. In fact, I’m often disappointed that the digital context tends to be too polite and respectful of the work (or maybe just superficial and lacking passion), and doesn’t really provide many opportunities to witness bizarre, conflicting, and surprising evolutions of the work or the artist’s figure. But this holds true for almost all forms of art nowadays. Transgression seems to be more about product/identity placement than about the sheer pleasure of making a scene or expressing one’s disgust freely. Big Brother is no longer a target for defiance and mockery, just a sea to swim in with water wings.

fakewhale

Founded in 2021, Fakewhale advocates the digital art market's evolution. Viewing NFT technology as a container for art, and leveraging the expansive scope of digital culture, Fakewhale strives to shape a new ecosystem in which art and technology become the starting point, rather than the final destination.

You may also like

12 Must-Visit Contemporary Art Galleries in London

London, renowned for its vibrant and dynamic art scene, is a treasure trove for contemporary art dev

Szilvia Bolla, Running Up That Hill at Glassyard Gallery, Budapest

“Running Up That Hill” by Szilvia Bolla, curated by Barnabás Zemlényi-Kovács, at Glas

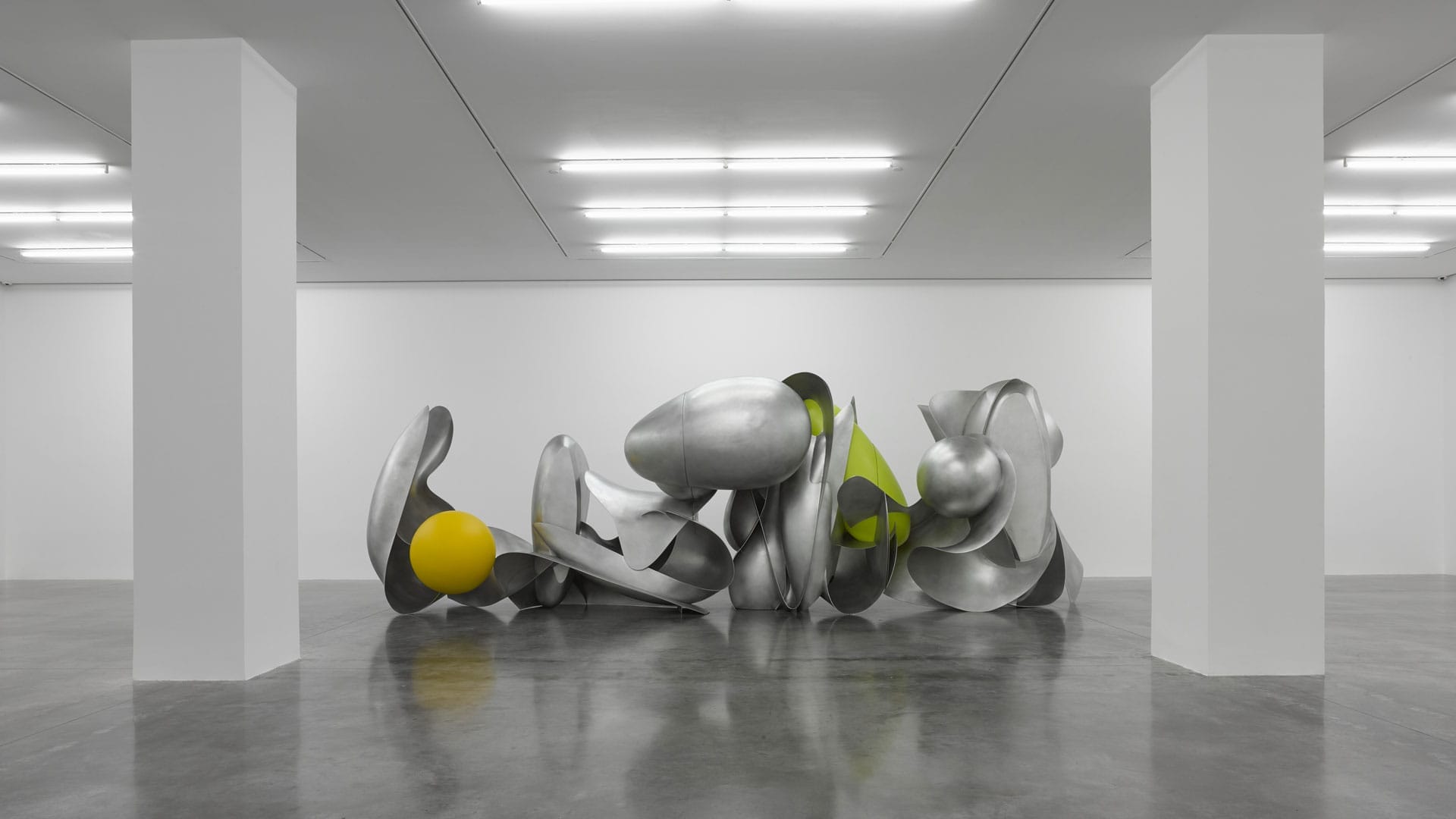

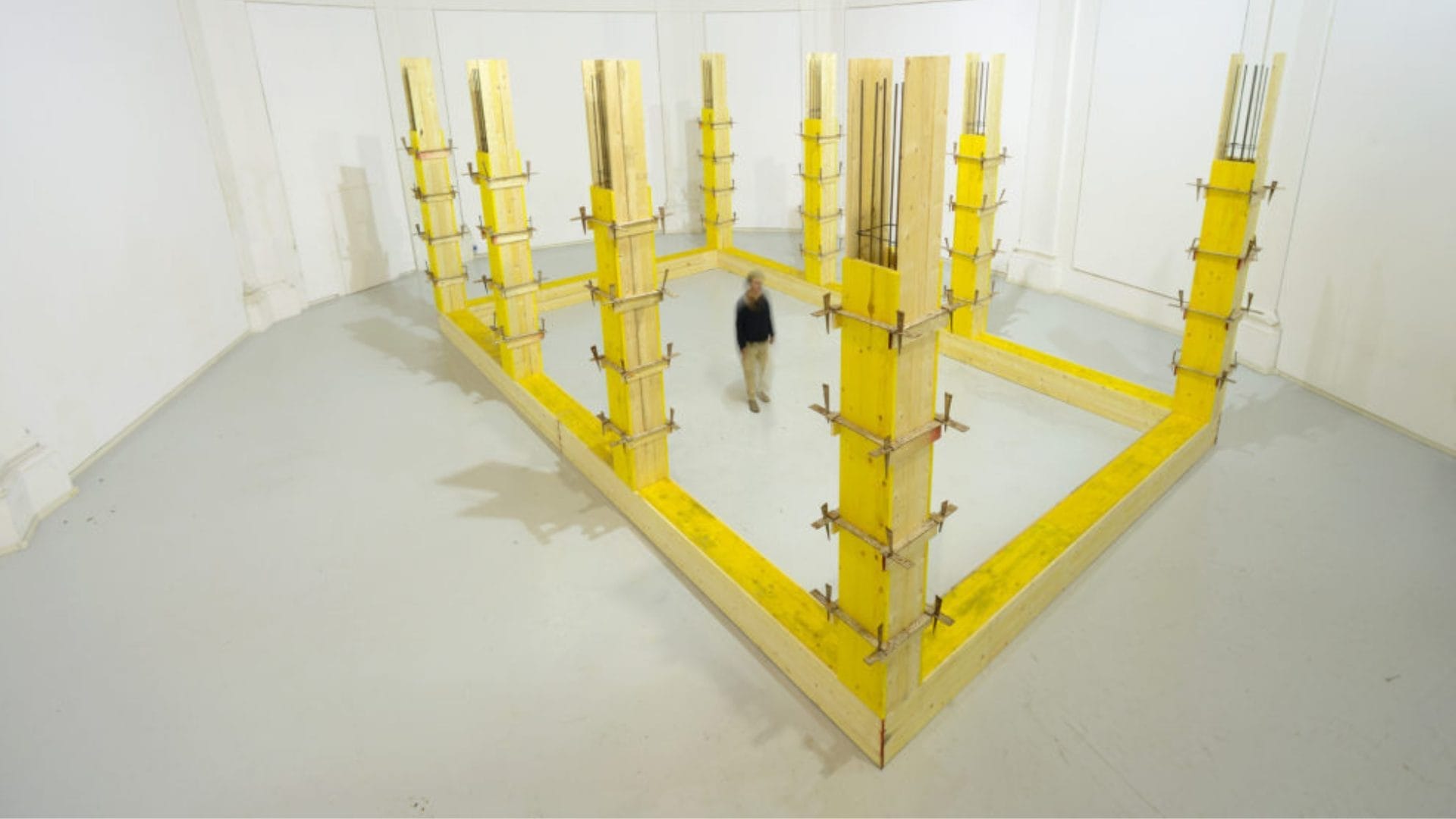

Between Precariousness and Structure: Fakewhale in Dialogue with Giovanni Termini

Giovanni Termini‘s art is a continuous dialogue with space, matter, and the tensions between b