Fakewhale in dialogue with Marlon Nicolaisen

Marlon Nicolaisen‘s practice focuses on a wide range of themes that span the digital and natural, exploring perception, physicality, and the boundary between object and subject. His works, which utilize technologies like 3D printing, laser cutting, and CNC milling, pose questions about complex concepts such as Posthumanism, liminal spaces, and the Uncanny Valley, challenging the viewer to reconsider the life and presence of objects.

We had the opportunity to talk with him, delving into his influences and the processes behind works like “Cradle-Coffin” and “Sidequest mod: fountain”, while also exploring his views on the convergence of art and technology.

Fakewhale: Your work seems to constantly explore the boundary between object and subject. What drives you to investigate this distinction, and how do you think contemporary technology is redefining these concepts?

Marlon Nicolaisen: Yes, I often engage with this threshold state. I find it fascinating that objects, which appear entirely inorganic, can gain a certain vitality through movement, for example. They can be understood as hybrids that may evoke emotions in the viewer. Through such exploration, one can perceive their environment differently and possibly develop a new relationship with objects. In my own work, I build a kind of relationship with these objects myself. What excites me most is witnessing the moment when I show my work to someone and see what associations it triggers.

Your installation Cradle-Coffin is inspired by Mori’s Uncanny Valley. How did you integrate this theory into your works, and what other reflections has this concept sparked for you?

The “Uncanny Valley” initially describes objects that appear human-like but are still clearly recognized as non-human. I find this concept particularly interesting because it deals with the perception of objects and our interaction with them. I believe that the distrust triggered by the “Uncanny Valley” today no longer primarily concerns tangible objects but rather AI or other autonomously acting processes that we can no longer fully control.

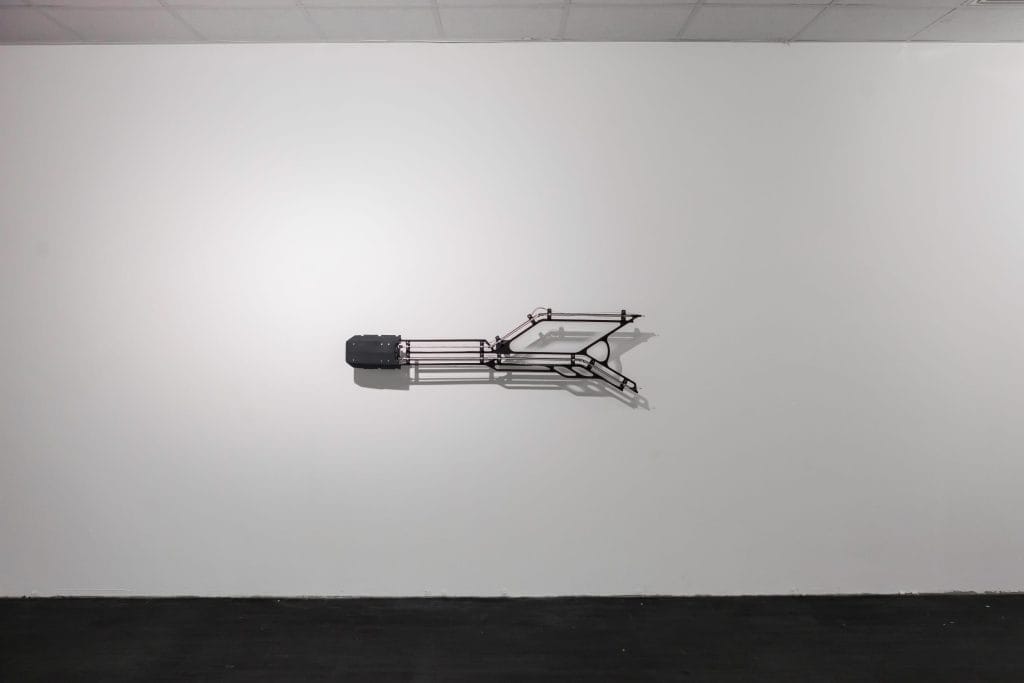

During my research for the Cradle-Coffin installation, I came across Mori and his theory. The “Uncanny Valley” reveals uncertainty about one’s own reality, and I find this uncertainty to be a particularly thrilling moment. However, I think this feeling can also be evoked in other ways. Therefore, my installation doesn’t have human features but instead a distinct vitality of its own.

The object integrated into the installation, which plays a central role, is a hybrid in relation to this uncertainty. On one hand, this object evokes exactly this type of uncertainty in me, but on the other hand, it is clearly not human and doesn’t aspire to be perceived as such.

You often use hybrid structures that mix organic and artificial components in your works, like Contraption and C7950ZN. What is the meaning behind this duality, and how do you hope it will be perceived by the public?

I particularly enjoy the contrast between these different components, as it clearly highlights the characteristics objects bring with them. This clarity allows a story to be told and makes the objects appear more organic. In almost all of my works, I don’t use organic materials, but rather plastic, metal, and glass, which emphasizes the differences. I believe familiar technical structures, like screws, are necessary to better categorize and visually grasp organic forms. Upon closer inspection, new details can always be discovered, and that’s what fascinates me: understanding how something works. I hope that my works also evoke this fascination in the viewer.

The relationship between movement and the perception of “vitality” is central to your work. How do you think movement transforms objects into animated entities in the eyes of the viewer?

I feel that we can assess very early on whether something is alive, and we quickly want to categorize things to understand what we are encountering. My works attempt to challenge this categorization. Irritability, metabolism, growth, reproduction, evolution, cells, and movement – these are the seven characteristics of life, but in a quick observation, we primarily recognize movement. I believe that movement facilitates emotional access and amplifies the impact. However, it is important to distinguish that objects with regular, rhythmic movements are often identified as machines.

You often speak about liminal spaces and how they influence the perception of the everyday. Can you tell us more about how space and the absence of human presence play a role in your installations?

When I speak of thresholds, I refer to the ambiguous categorization and the resulting uncertainty. The works could be interpreted as dark visions of a future without humans, but I don’t want to dictate this interpretation. A positive reading could be equally intriguing. Regarding space, I believe a certain emptiness can encourage focus and individual interpretation of what’s happening. Entering a calm, humanless space can create a situation that might even feel dreamlike. Light plays an important role here, as it guides the gaze and shapes the space.

Your works, like Quick Rest, often play with the ambiguity between familiar objects and unknown entities. What do you hope the viewer experiences when confronted with these creations?

This work is a good example of the interplay between the environment and the object itself. The feeling of familiarity is supported by the table and the fur on which the creature curls up. The movement brings the scene to life. This encounter creates a confrontation with the everyday, potentially creating a liminal situation where the impact goes beyond the visible.

In ULAN, you explore the concept of machines developing a life of their own. Do you believe that machines are truly becoming more opaque and incomprehensible to us?

Yes, I believe that the surfaces of devices and machines are becoming smoother and shinier, while we know less and less about the knowledge behind them. In ULAN, I liked the idea of creating something that cannot actually fulfill any task, but looks like it could. In this way, the object gains a function through interpretation. ULAN is visually influenced by exposed machines.

You use technologies like 3D printing and laser cutting to transform digital projects into physical objects. How do you balance the digital and physical worlds in your creative process?

A truly exciting moment was the first time I 3D printed something, and the fascination has stayed with me. Using various modeling tools on the computer, you can freely create shapes, and shortly afterwards, you hold exactly that form in your hand. It feels a bit like being a child who cannot wait for the print to finish. The feeling of having the object afterward is often entirely different from what it looked like on the computer; the proportions are almost always different from what you imagined. Over time, you learn how to estimate the sizing.

You’ve worked on numerous projects exhibited in both physical and digital spaces. How does your artistic vision change when considering an exhibition space versus a digital context?

What is exciting about the exhibition space is the experience. The space is a place of encounter where the exhibiting person has complete control over what happens there, allowing for an immersive spatial experience. I find this type of engagement with a place the most exciting. In the digital space, control is even greater, allowing for physically impossible scenarios. However, the downside is the limitation to one’s own decay, as you are unable to fully immerse yourself in the world behind the screen. I use the digital space to create visualizations but also video projects.

Looking to the future, what technologies or themes do you believe will continue to influence your work? Do you have any new projects in mind that will further explore the boundaries between the natural and the artificial?

I can imagine that moving from conventional interfaces to neural interfaces between the digital and the human will be very exciting. The accessibility of new technologies also continually offers new incentives to keep working in this space. I will continue to explore these threshold areas and will try to find new approaches and perspectives in doing so.

fakewhale

Founded in 2021, Fakewhale advocates the digital art market's evolution. Viewing NFT technology as a container for art, and leveraging the expansive scope of digital culture, Fakewhale strives to shape a new ecosystem in which art and technology become the starting point, rather than the final destination.

You may also like

How to craft an art tribe with open source DNA?

Decentralized Dynamics and Protocols: A New Type of Art Manifesto in the Internet 3.0 Era?” URL fr

Fakewhale in dialogue with Norma Jeane

Recently, we engaged in an ongoing dialogue with Norma Jeane and found ourselves captivated by the i

Donghoon Gang, attacca, at BOAN 1942, Seoul

“attacca” by Donghoon Gang, at BOAN 1942, Seoul, 26/07/2024 – 10/08/2024. The Dyad