Fakewhale in Dialogue with Fabian Lehmann: Exploring the Intersection of Materials, Media, and Digital Duality

Fabian Lehmann’s work exists at the intersection of materiality and memory, where digital and analog processes collide in a continuous dialogue. His practice explores the fragility of digital media, the historical weight of classical forms, and the shifting perception of permanence in an era defined by technological acceleration. Through Series like “Säulen.jpg” and other works in the Exhibition IN(STABILITIES), Lehmann questions how cultural memory is curated, distorted, and preserved in the digital age. We at FakeWhale had the pleasure of speaking with him about these themes, uncovering the layers of his artistic inquiry.

Fakewhale: You often emphasize the fragility of digital media and their ability to distort historical memory. How do you think digitalization is transforming cultural memory and our understanding of historical continuity?

Fabian Lehmann: Digitalization is profoundly transforming cultural memory and our understanding of historical continuity. While digital media significantly expand access to historical sources and knowledge, they simultaneously challenge the materiality of memory. Traditionally, memory has been preserved through physical carriers—from cave paintings and books and so on… These physical media were not only repositories of information but also cultural artifacts that endured over centuries.

Digital media, by contrast, are characterized by a paradoxical fragility: on the one hand, they promise potential immortality; on the other, they are subject to technological obsolescence, data loss, and institutional power structures. While analog media are threatened by physical decay, memories bound to digital media require constant maintenance and migration. Without such measures, information across all domains may disappear—whether due to technical incompatibilities or the vanishing of platforms and formats. The very concept of decay must be reconsidered in this digital context.

Moreover, digitalization is reshaping the selection and curation of memory. In a world overwhelmed by digital information, a renewed question emerges: Who decides which memories are preserved and which are forgotten? While traditional archives were managed by institutions with more or less clear hierarchies and structures, digital platforms are often shaped by algorithmic decisions. These mechanisms can not only selectively shape cultural memory but also distort it by privileging certain narratives while rendering others invisible. Digital media not only determine which memories remain accessible but also influence how we understand and interpret history. The omnipresence of digital cultural techniques enables, on the one hand, a democratization of access to historical information. On the other hand, it introduces new challenges: the potential for manipulation, the risk of overload due to unfiltered data volumes, and the danger of collective memory becoming dependent on a few powerful platforms.

Ultimately, the question arises whether digital memory is truly “immortal” or whether, like a crumbling temple, it will one day become inaccessible. The long-term preservation of cultural memory requires not only technological solutions but also institutional and societal responsibility. We have to think about new strategies not only to store digital memory but also to critically reflect upon and actively curate it. After all, the way we deal with memories today will determine how we think about the future.

In your exhibition “(IN)STABILITIES,” you explore the tension between historical symbols of stability, such as Greek columns, and the ephemeral nature of digital environments. What inspired you to focus on this contrast, and how do you think it reflects the current cultural moment?

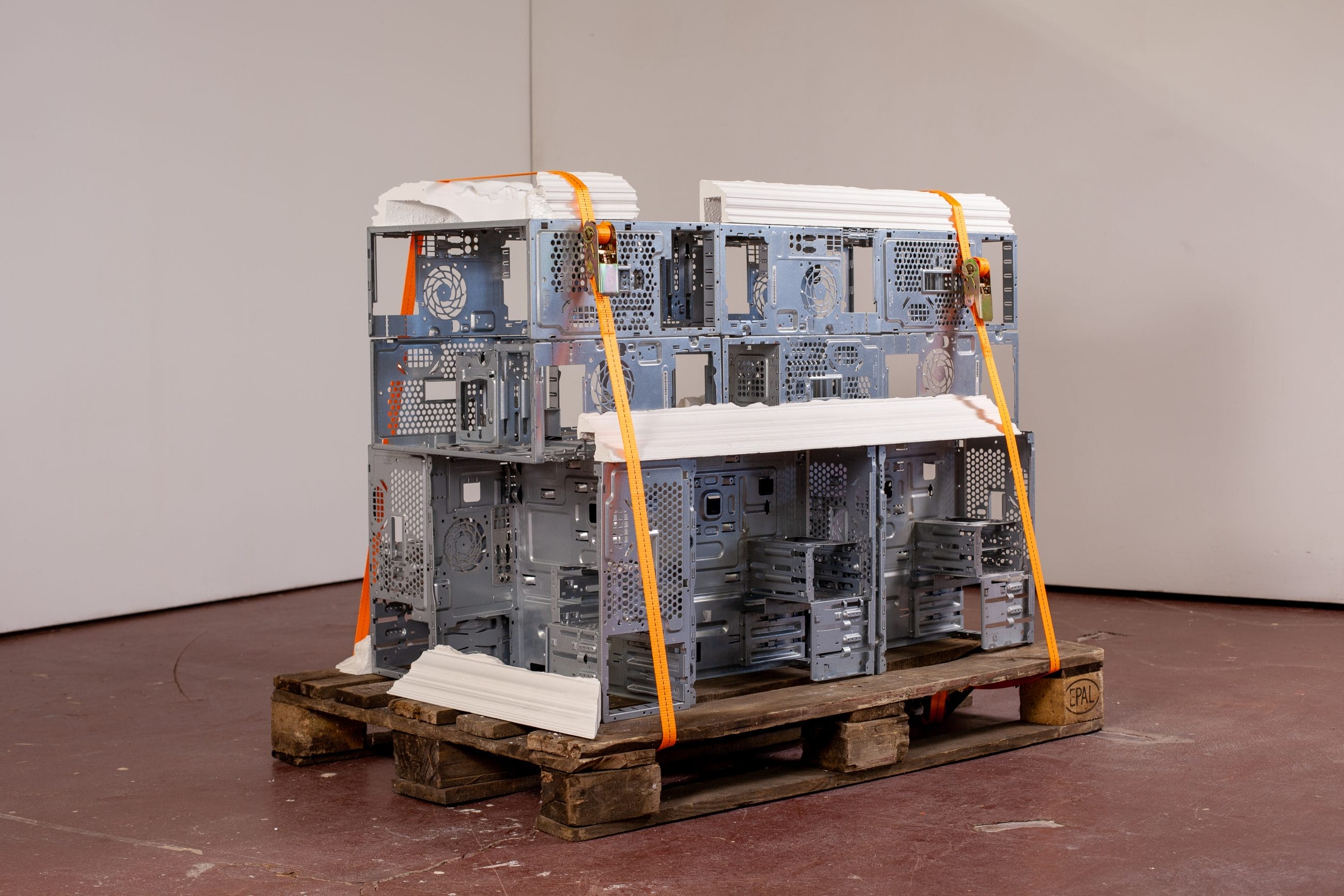

In the exhibition, I explore the tension between historical symbols of stability, such as Greek columns, and the fleeting nature of digital environments. How can common assumptions about antiquity as a symbol of stable, material structures and about digital media as ephemeral and ever-changing be questioned? To what extent could the juxtaposition of these two realms itself be subject to critical reevaluation?

This contrast stems from two of my central areas of interest: looking into the past— shaped by archaeology, history, and art history—and engaging with contemporary digital cultural techniques. It was only natural for me to connect these two fields in my work. During my studies at the art academy in Leipzig, I had the opportunity to visit Athens as part of various projects. Direct engagement with Greek antiquity strongly influenced the works I presented in (IN)STABILITIES. My focus is not merely on an aesthetic approach to past epochs but rather on using form—and the accompanying worldviews of the past—as a means to better understand the present, and thus, to envision the future.

Greek columns symbolically represent permanence and cultural continuity. Digital media, on the other hand, exist in a state of constant transformation—they are immaterial, change at an unprecedented historical speed, and are always dependent on the technological infrastructure that supports them. At a time when supposed stabilities— political, social, and technological—are repeatedly being questioned, I am particularly interested in the dialectical movement between preservation and deconstruction. Which historical stabilities should be reinforced, and which must be critically examined or even dismantled? A lot of the current questions are by no means new: some of the crises and challenges we face today have, in similar forms, already occupied our ancestors 3,000 years ago. This realization can be reassuring—problems seem less unique—but also sobering when one recognizes that certain challenges have remained largely unchanged over millennia.

Ultimately, my work seeks to create a space for reflection on the present through the lens of the past. By combining historical symbolism with modern technologies, I investigate how our understanding of permanence and transience is evolving in the digital age—and how we can navigate this tension …

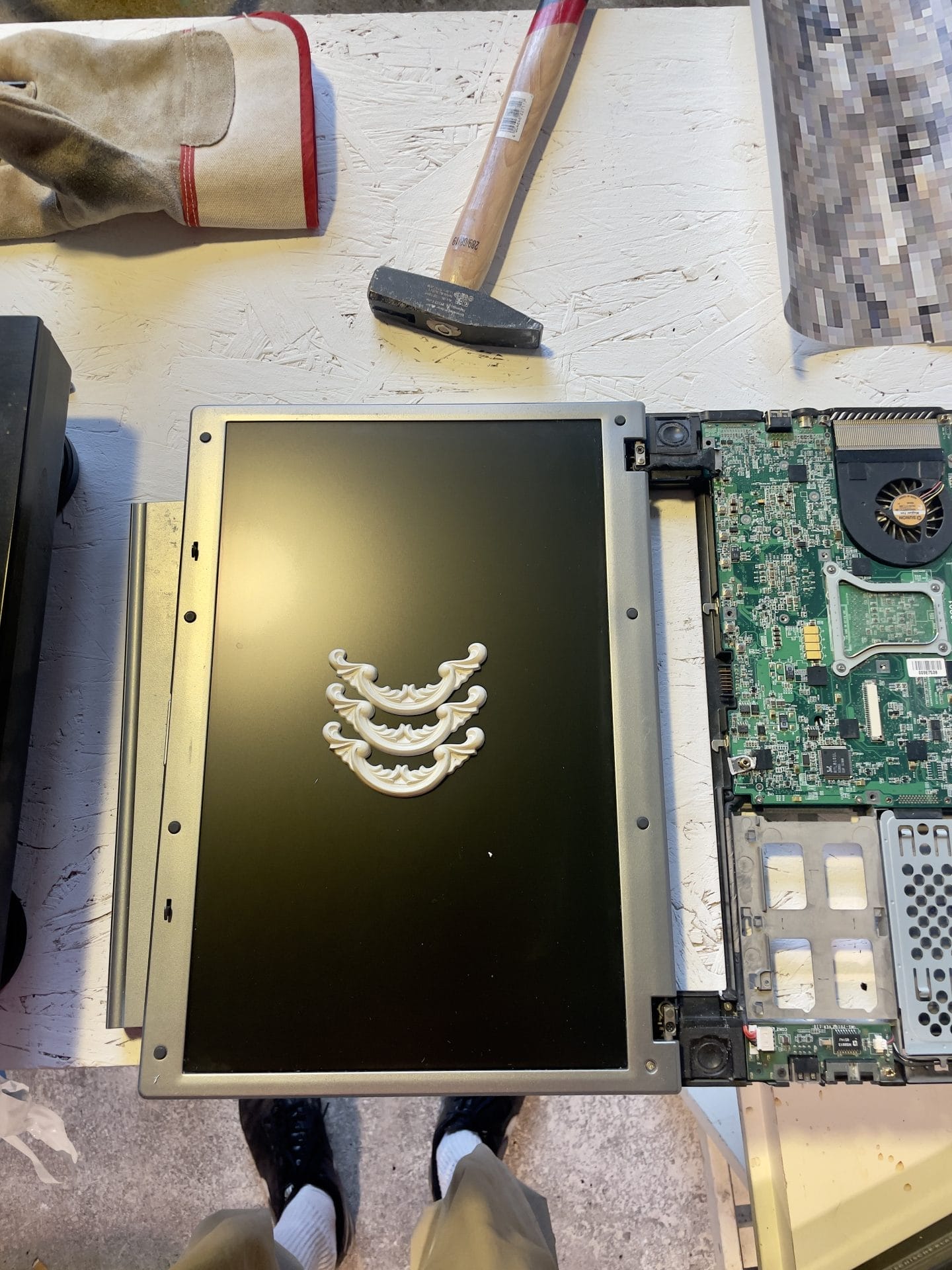

The series Säulen.jpg uses rusted metal frames to encase photographs of ancient monuments modified with artificial intelligence. Could you elaborate on how this fusion of analog and digital materials contributes to your reflection on permanence and decay? Additionally, could you explain further the relationship between photography and artificial intelligence in this series? On this subject, what is your opinion about artificial intelligence applied to visual arts? What kinds of perspectives do you think it opens for the future, and what has it already opened so far for artists working in fields like yours?

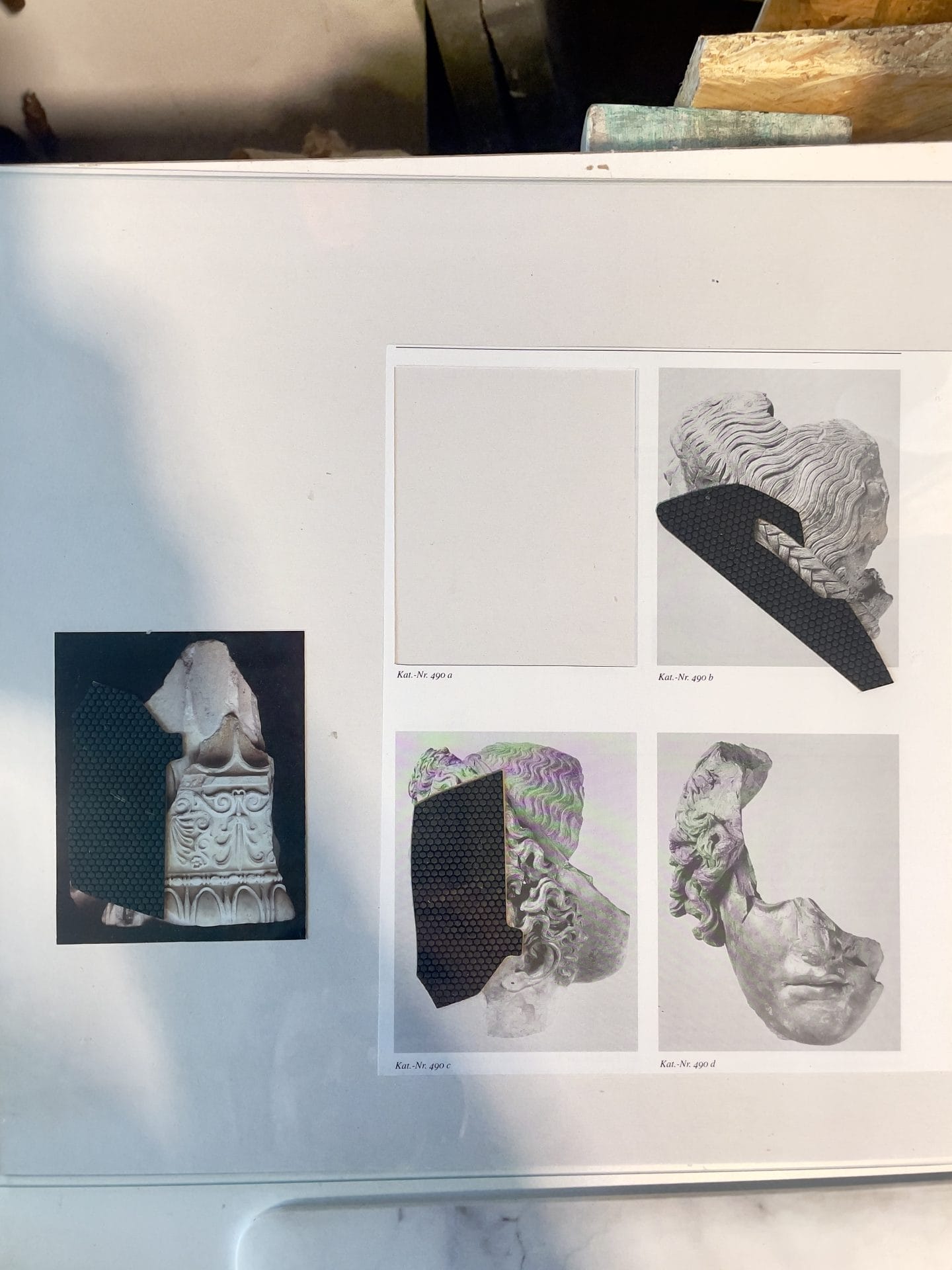

In my series Säulen.jpg, I work with the tension between analog and digital materials to explore questions of permanence and transience. The rusty metal frames surrounding the photographs represent physical stability but also the relentless process of decay. Encased within them are images of ancient monuments—symbols of endurance—that I have edited by using artificial intelligence. Through these interventions, I question whether and how our perception of stability shifts through technological developments.

I am not only interested in the material aspects of decay and preservation but also in how AI reshapes our understanding of images and art. Generative AI is not an entirely new technology, yet it brings fundamental questions about image production and reception back to the forefront: How does AI affect our trust in images? What forms of visual reality emerge from its application? In my work, I consciously embrace this uncertainty by modifying parts of the images with AI, reflecting on whether our “images of stability” can withstand new technological paradigms.

For me, engaging with AI in art is not a matter of acceptance or rejection but one of critical reflection. Artists have always been curious about new tools. However, while previous technological revolutions, such as the invention of photography, took decades to transform art (and society), AI is accelerating this process at an unprecedented pace.

Like past artistic revolutions, AI has the potential to push boundaries, generate new forms, and inspire new ways of thinking. Yet it not only changes how art is made but also how we discuss and evaluate it. The debate around AI in art is becoming increasingly polarized: on one side, abstract theoretical discourse; on the other, a fixation on market value and popularity. But beyond these extremes, art’s fundamental task remains unchanged: to ask questions in order to engage with the past, present, and future.

The new tools are here—we will use them. But the crucial question is not whether we create art with, about, or against artificial intelligence. Far more important is asking the right questions: How does AI alter our relationship with art? What paradigms does it create? And what transformations does it trigger in our understanding of images, history, and “reality”?

How do you select the materials for your installations, which blend tactile and digital elements, and how does this fusion shape the viewer’s experience? Do you have a preferred medium, or do you enjoy working across multiple media simultaneously? How do you navigate the interplay between analog and digital processes in your work, and what challenges arise when bridging these two worlds?

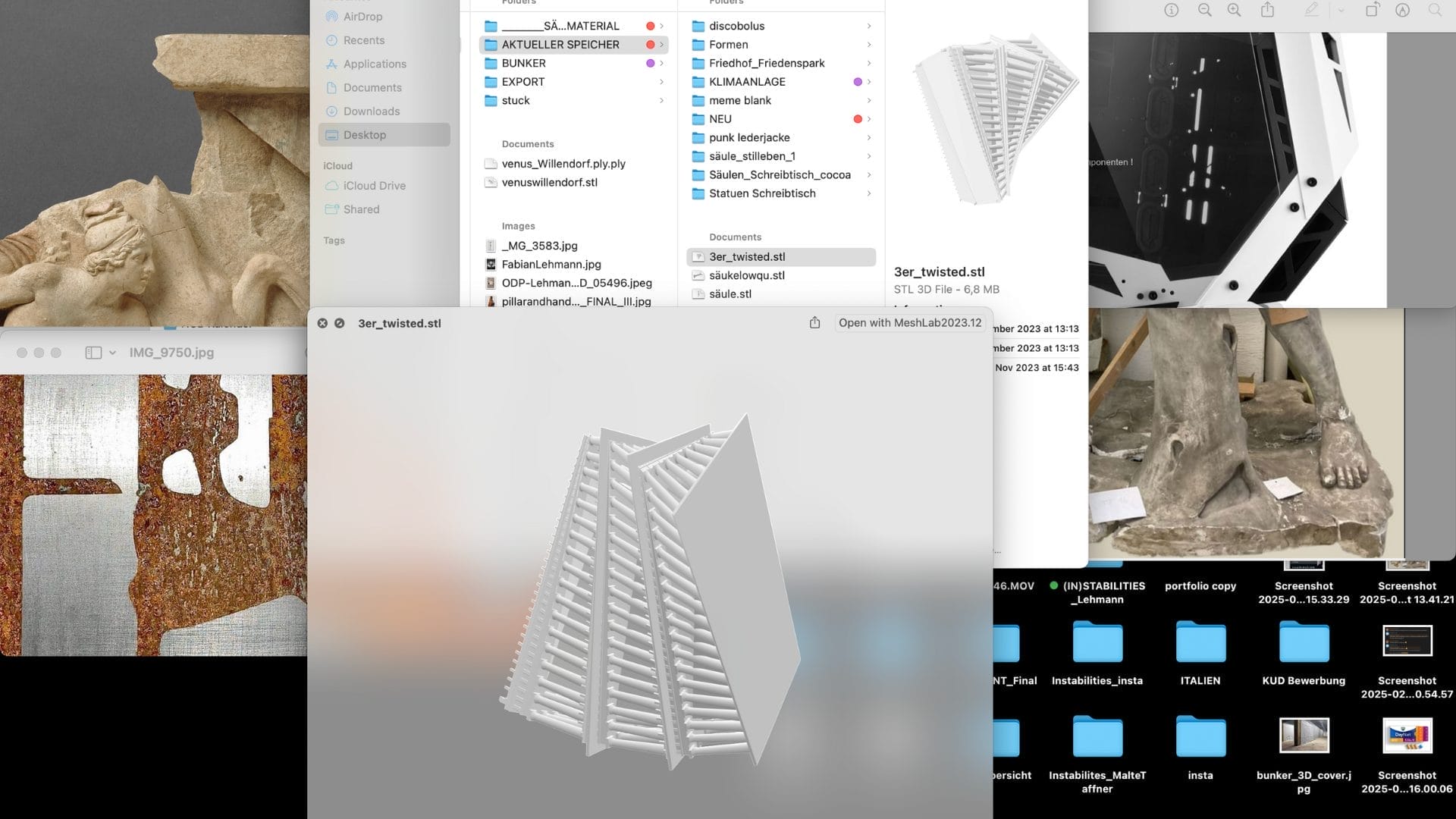

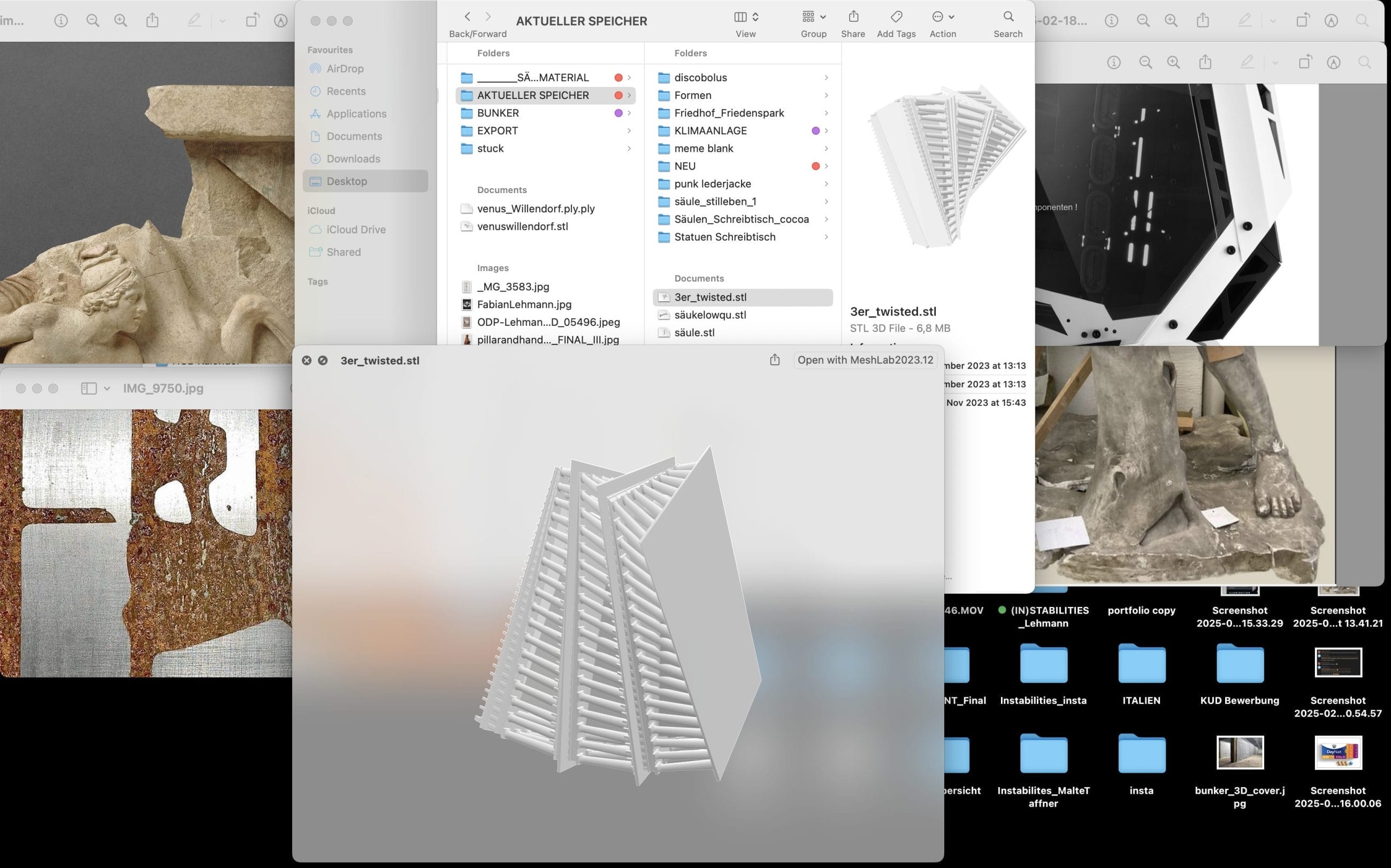

My work in the studio is strongly shaped by the collection and assemblage of diverse materials—a process where I don’t make no distinction between analog and digital sources. To me, both are equally valuable and equally fascinating. The first step in my process is gathering materials, which are often unconsciously preselected based on my artistic interests and the themes I engage with. There is no hierarchy in this selection: objects and materials from a scrapyard can be just as relevant as items from online shops or digital fragments found in virtual archives or on social media platforms.

A key part of my artistic practice is observing the relationships between these collected materials. I arrange, sort, and place them in new contexts to highlight their similarities and differences. I am not only interested in formal or aesthetic aspects but also in the conceptual tensions that arise from juxtaposing heterogeneous materials. What fascinates me most is the contrast between industrially manufactured “ready-made” objects and those I create myself. I explore how these two categories differ in terms of materiality, perception, and meaning—and what new contexts emerge when they enter into dialogue with each other. What happens when an industrially produced object is altered or distorted through artistic intervention? How do the surfaces, structures, and textures of a machine-made object differ from those of a handcrafted element?

These questions accompany me throughout the entire process. Often, new insights only emerge through direct physical engagement with the materials—through experimentation, combination, and transformation. My practice is therefore an open, exploratory process in which I rarely know at the outset what the final outcome will be. (#yolo)

The final step is to translate this collection into a format, into an expression. Processes of translation, transfer, and transformation play a central role in this stage. I am particularly interested in how certain contents, forms, or aesthetics change when they migrate into another medium. It is precisely through this media transformation that the unique characteristics of materials and techniques can be better understood in a dialectical relationship.

My practice deliberately navigates the space between analog and digital processes. To me, these two worlds are not contradictory but complementary. Digital technologies open up new possibilities for image and object creation, but it is only in combination with

physical materials that the ruptures and contrasts emerge, which are central to my work. This duality raises fundamental questions: How does our perception change when a digital object gains a physical presence? And what role does the artist’s hand play in an increasingly automated, algorithm-driven world?

Ultimately, my studio is a place where these questions unfold in a practical way. It is a space for experimentation, material research, and the intersection of diverse influences. I enjoy working with different media because each material and technique brings its own logic and vocabulary. Whether I work with plastic, plaster, 3D printing, or other forms— the choice of medium emerges from the process and from the dialogues between the individual elements. I am also super fascinated by the confrontation between industrial mass production and individual human interventions—a tension that runs through much of my work.

Looking to the future, what projects do you have in mind, and how do you imagine these technologies could evolve your exploration of the interaction between materiality, memory, and instability?

To be honest, I simply want to keep working. I feel that my engagement with certain themes and techniques is becoming more refined, and I’m eager to continue exploring these directions. I can imagine that generative AI, particularly in relation to 3D modeling and image making, will play a more significant role in my practice—this is something I find incredibly interesting.

At the same time, many ideas, materials, and concepts have accumulated in my studio and in my mind over the past months. Unfortunately, I haven’t had the time to take the next step of organizing and developing them further, but I am optimistic that I will soon find the space to do so. One exciting opportunity in this regard is an upcoming residency in Romania, where I will have dedicated time to focus intensively on 3D printing techniques and push forward certain aspects of my work.

Another project close to my heart is the International Art Center Petersberg (www.ikzp.online), which I founded in a former DDR bunker in a rural area near Leipzig. Together with fellow artists and friends, I curate exhibition formats inside the bunker, and in August 2025, we will launch a summer academy—an extended residency where we will work on-site, develop formats, and collaborate with other artists.

I’m also looking forward to several exhibition projects in 2025, including a presentation of my work in public space, which offers an entirely different framework for me. So, yes— there’s definitely no risk of boredom. The future remains exciting!

fakewhale

Founded in 2021, Fakewhale advocates the digital art market's evolution. Viewing NFT technology as a container for art, and leveraging the expansive scope of digital culture, Fakewhale strives to shape a new ecosystem in which art and technology become the starting point, rather than the final destination.

You may also like

FAKEWHALE in conversation with Jan Robert Leegte

On the occasion of the upcoming exclusive Fakewhale-curated release Walled Garden, launching June 5

Beatriz Olabarrieta, “Proximity,” at Shahin Zarinbal, Berlin.

DECEIT…on the move. One of our* tasks is to give you a WARNING, warn you about invisible fields

Nicolás Rupcich, TRL at ZiMMT, Leipzig

“TRL” by Nicolás Rupcich, at ZiMMT, Leipzig, 18/09/2025 – 28/09/2025. What remains of