Fakewhale in dialogue with Dev Harlan

We have been following Dev Harlan’s work for some time, and we are fascinated by his ability to explore the complex relationship between technology, landscape, and anthropogenic change. His artistic practice investigates how human societies and technology are intertwined and integrated into nature, challenging the narrative that sees them as separate entities. Recently, his work has taken a new direction with the project “The Dithering” which uses virtual desktop emulation as a lens to examine climate apathy. We are excited to discuss these new developments, as well as his hybrid works that blend the digital and physical worlds, opening new avenues of reflection on our technological era.

Your background is unconventional for an artist. How has your education shaped your artistic practice and the themes you address in your work?

That is always a complicated question as I am largely a self-taught artist. I grew up in Silicon Valley and was homeschooled for most of my childhood.

Instead of attending high school I enrolled in community college at fifteen, taking a variety of art classes.

Not surprisingly I had little discipline for formal education and soon left to work in the emerging dot-com boom in San Francisco.

I became immersed in the video art and hacker subculture, while taking on odd jobs ranging from testing routers to programming early websites.

My early approaches to art making were through video programming, hardware hacking and repurposing discarded technology, though I lacked a critical framework for much of what I was doing then. Moving to New York shifted my perspective and my process and I began to work with sculpture and video projection on a larger scale.

I refined my practice through residencies, including a pivotal one at the Frank Lloyd Wright School of Architecture in Arizona, where Wright’s philosophy of “learning by doing” felt appropriate. In the Sonoran Desert, I found inspiration in the landscape’s geological formations. I began casting and 3D scanning rocks and exploring the poetics of the processes that shaped the Earth. Later residencies in Joshua Tree deepened this engagement with the desert. The more I studied the landscape the more it became difficult to ignore the effects of anthropogenic change. The most obvious in the desert being strip mines, I visited many.

These are inextricably linked to technology when considering that very single electronic device, battery or screen contains elements that must be extracted from the Earth.

My interest in geology grew, though my attempts at self-education left gaps.

Eventually, I returned to school to study the sciences and was ultimately accepted to the Earth Science program at Columbia.

Certainly things I’m exposed to here find their way into my practice all the time, but perhaps this biggest shift in thinking is that the Earth System is complicated, multi-layered and that rocks are only part of the story.

My attention has also shifted towards climate science, due in part to the founding of the Columbia Climate School, and also because I am drawn to the depth and complexity of the problems.

Currently I am doing research on glacial ice loss in Greenland and naturally I am thinking of how this theme may be expressed artistically within my work as well. Ultimately my goal is to foster a transdisciplinary practice between art and science.

Are there any artists or significant figures who inform your creative practice? How does their legacy reflect in your works?

Continuing the education theme, I had the opportunity to take an insightful class with American Artist at the School for Poetic Computation in NY. I had already been influenced by their work, but the course pushed me to confront how technology functions in my own practice. At some point it becomes disingenuous to use technology and the spectacle of the digital without addressing its complicity in social and environmental ills.

Nam June Paik left a lasting impression on me as the first museum show I saw as a teenager. His use of television sets and other technologies were more than clever manipulation–he recognized television’s dual nature as both a tool of mass media control and a subversive platform in the hands of artists, which he used to great effect.

Other artists I pay close attention to include Sarah Sze, particularly the strength and candor in exposing artistic process; Thomas Saraceno, who blends art, architecture, and science in a truly transdisciplinary way; Both Jenny Holzer and Hito Steyerl have shaped how I think about narrative and the power of language within visual and time-based media; Recently I have been returning to re-examine work from the JODI collective and John Maeda, (subversive computing and engaging with the language of computation, respectively) who I see informing other figures I admire such as Cory Arcangel or Rafael Lozano Hemmer.

In Hegemony of Screensavers (Artifacts), you use digital brushstrokes to make an ironic connection to computer screensavers while including 3D scanned objects like rocks and discarded technology. How do you see this hybridity acting as a critical response and polemic to digital formalism?

Hybridity is a good way to put it, there is a lot going on in this work. I had been thinking about the logic of screensavers, both as a practical solution to the early problem of CRT burn-in, but also their role in showcasing computer graphics. Naturally the most efficient (and ecological) form of screen saver would be to simply turn it off, but this is somehow contrary perhaps to a Puritan American disdain for idleness, we prefer to show that something is always working. An outcome of this logic is the role of the screensaver as a tech demo showing off the latest advances in graphics hardware and software algorithms.

Unfortunately I believe that much digital art succumbs to the logic of the tech demo as well, which privileges a digital art formalism as an end to itself–such formalism has been widely abandoned in other disciplines since the end of the modernist era.

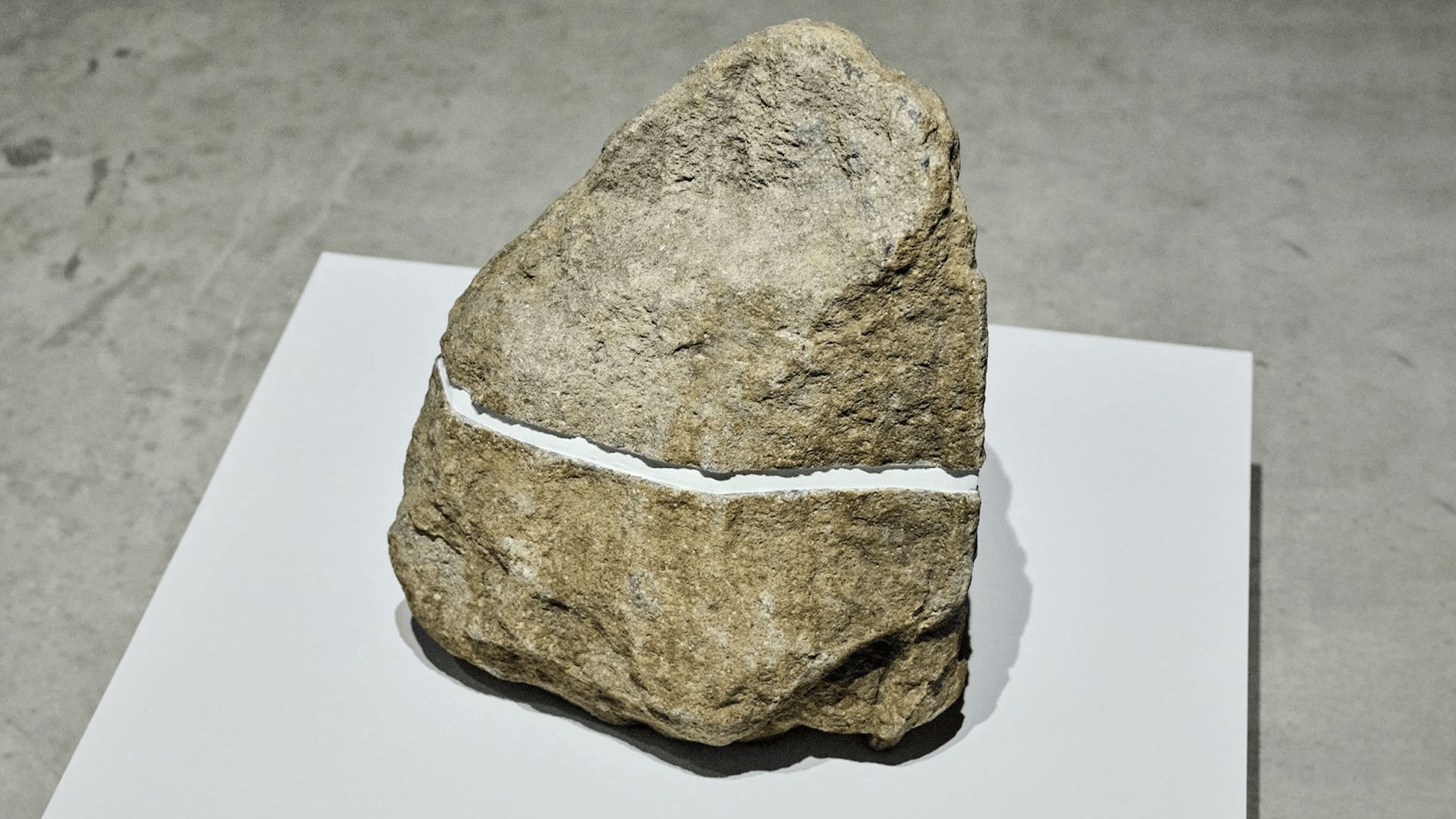

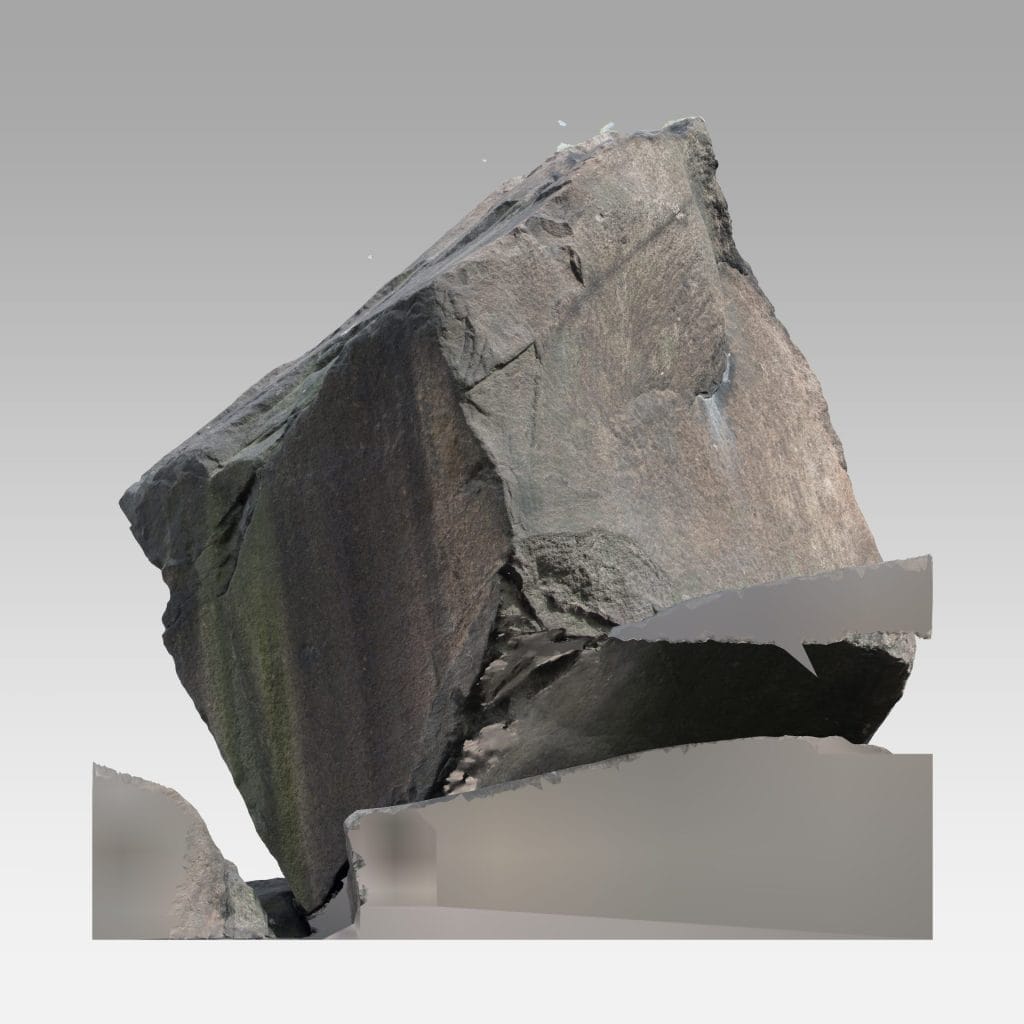

Moreover, digital formalism, often linked to the immaterial, supposes a totalizing liminality that conveniently ignores all the messy physical infrastructure that is required to support it. In the work Hegemony of Screensavers, 3D scans of rocks and boulders alongside technological debris points to the extraction of natural resources on which all technologies depend. Despite the characterization of the digital as a weightless, infinite realm, it is only possible through a global system of physical consumption and waste.

What was the process behind the 3D scanning of rocks, boulders, trash and other found objects, and how does this process create narrative in your work?

Like many artists I am primarily scanning using 3D photogrammetry as cameras are ubiquitous and there are many software options. I prefer to use an SLR but have gotten perfectly usable scans shooting video on a phone. I find the digital scan a compelling way to reference things in a way that retains an indexical relationship to the original thing. Like photography, the scan is a trace of reality that, to quote Susan Sontag, is directly stenciled off the real. This allows for greater narrative potential as the scan brings with it a richer materiality with all the flaws, imperfections and embedded narratives of real world objects.

What becomes interesting to me is the tension between material and immaterial objects, and I am often deliberately mixing materialities in order to dislocate the hierarchies between them. The stone surface has an immutability that suggests stability over time. The digital image or model is in fact an ephemeral collection of electronic impulses on a screen, or magnetic traces on a hard drive that could be wiped out instantly. What if the stone becomes an immaterial digital model? What if the immaterial model is carved in stone? What if both of these representations are combined?

Your hybrid sculptures, which combine obsolete technology with materials like sand and stone, also point to a tension between technology’s ephemerality and geological deep time. What led you to explore this contrast?

At the simplest level, I recall thinking about a slab of marble, which is compressed from limestone at extreme heat and pressure. Limestone is basically a conglomerate of microfossils and shells of marine organisms. What would marble look like if it were compressed from human fossils and the contents of our landfills? What does a computer look like when it has been crushed for 100 thousand years at 500°C?

In the present tense I am interested in the so-called ‘geological turn’, a recognition of the complex role of the lithosphere, and the unprecedented way in which it is being altered. Indeed many of the proposed definitions of the Anthropocene epoch revolve around defining a specific place in geological records where humans have left indelible traces, such as increased CO2 concentrations in stone, or radioactive particles from nuclear weapons testing. In my work, the depiction of computers or devices from the past is not intended as sentimentalism, rather I am interested in considering them as future fossils, literally flattened into the geological strata. When this thin layer of recent human activity is seen against the kilometers thick record of Earth’s history, it brings greater clarity to our relative position, and I hope greater moral clarity as well.

Your new work on virtual desktop emulation marks a shift in your artistic practice. Could you tell us more about this direction and what prompted you to explore these emulated digital environments as an artistic medium?

Sure, the emulated Apple desktop as a standalone artwork is a new direction in my work, and yet it also marks a return to some of my earliest projects. Back in San Francisco, I started collecting obsolete Macintosh computers, which I found on the street or in thrift stores. They seemed archaic to me at the time, though they had only recently become obsolete. Through a serendipitous connection at an e-waste center I acquired over 100 computers, some of which I still have. Lately I have had a renewed interest in exploring their artistic potential, creating sculptures and installations that incorporate functional machines running software art written in C and Applescript. These objects carry personal histories—the wear and tear, files left behind or university names etched into the plastic. The Classic Macintosh also alludes to the larger narrative of late 80s excess – a moment of techno-optimism and marketing hype around desktop computing which prefigured the dawn of the internet. Yet in the same years in which Tim Berners Lee was releasing the first functional web server, the IPCC was also publishing the first Climate Assessment report. It would not receive nearly as much enthusiasm. While reading through this document and comparing it to contemporary climate science it is incredible how accurate some of the 1990 predictions were, and also saddening how much of the fundamental science was already established.

Combining these two interests suddenly made sense to me – a historical research project around the nascent IPCC set in the context of a popular desktop operating system of the time period.

This theme unfolds through generative graphics and digital artifacts viewed within a sculptural installation of computers, stones, and found objects. Beyond the gallery, the desktop emulation allows viewers to engage more intimately with this same material on their own terms, offering an added layer to the experience.

How do you see the idea of a “dithering” algorithm being related to climate inaction?

The concept is not a direct correlation between the two but rather a play on words. I owe this connection to sci-fi author Kim Stanley Robinson who coined the phrase “The Dithering” in the novel 2312. Here he uses the original meaning of the word dither–to be hesitant or indecisive. In the novel, future historians use the phrase “The Dithering” to periodize the first half of the 21st century in which decades are lost to bickering and apathy amongst world governments. While this novel was published over 10 years ago the phrase comes to my mind often and still feels like an apt characterization of the present tense.

The project takes on a double meaning with the more technical meaning of the word dither, meaning a computer graphics algorithm used to achieve smoother aliasing when rendering an image at a lower bit depth. The original Macintosh had a bit depth of exactly one, literally black and white pixels. So within the project, dithering is everywhere, visually within images and icons, and ethically within the reflections around climate denial, inaction and irreparable losses.

In The Dithering, you refer to the inadequate responses to the climate crisis from the 1990s onward. Looking at the present, what do you think artists can do to drive real change in this area?

That’s really the urgent question isn’t it? While my focus here is on 35 years since the first IPCC report, I’m reminded that the climate story starts even earlier—certainly with the Keeling Curve, the first solid CO2 data from the Mauna Loa Observatory dating back to 1958. Perhaps I should think about emulating a UNIVAC next?

But when you look at how much conclusive science we have and how clear the problems are, the real issue becomes obvious. It’s not just a scientific problem—it’s cultural. We see inaction and disagreement from governments, industries, and ordinary people. The problem lies in our ethics, in deeply ingrained cultural values. Given this condition, isn’t culture where art can operate most effectively, challenging and shifting those values? Unlike scientists artists can be speculative and provide provocations that drive conversation and change narratives. If the world is a story we tell ourselves, artists are in a unique position to start telling new stories. I often think of Donna Haraway’s phrase “staying with the trouble,” which calls for a critical engagement that is beyond just art making, it’s about how you live your life. Like really grappling with the tough questions rather than generating them with ChatGPT.

In your artistic practice, there is a constant reflection on how technology and nature are not separate entities but rather intertwined with one another. How do you see this theme evolving in your future works and upcoming projects?

Yes, things are always evolving. The nature vs. culture theme has a lot of implications, a big takeaway being that a hierarchical arrangement which places humans at the top is the type of thinking that has led to the current ecological predicament whereby human civilizations are no longer sustainable. To move beyond this shallow reflexivity, humanity requires a new optimism, one that rethinks its position within nature holistically, with humans in a rhizomatic and networked relation to all living things.

Some have coined this shift in thinking as “the regenerative turn”, which I explored in a recent video work made of 3D scans ranging from rocks, trees and human artifacts sandwiched in between. Narrative text describes various ecological predicaments, and ultimately suggests that plants will take up stewarding ecology if humans are not up to the task.

Something else I’ve been thinking about is how to sonify seismic data from glacial calving events in Greenland. They are a bit like mini glacial earthquakes, but slower. Seismic waveforms are recorded from everything that happens on the Earth, ice slowly cracking, sudden landslides or mountains collapsing. The global seismic network is like putting an ear to the lithosphere and just listening. It is fascinating that much of what was considered ‘noise’ previously can now be identified. I am thinking about a project on this theme of listening to the Earth, literally, through seismic networks and mapping the sounds to the changing conditions of Greenland’s glaciers.

And lastly, I am working towards a larger body of work within the “Dithering” theme which I hope to be able to share soon!

fakewhale

Founded in 2021, Fakewhale advocates the digital art market's evolution. Viewing NFT technology as a container for art, and leveraging the expansive scope of digital culture, Fakewhale strives to shape a new ecosystem in which art and technology become the starting point, rather than the final destination.

You may also like

Blockchain As A New Medium For Art

The symbiotic relationship between artistic ingenuity and technological advancements is continually

20 – The Baptism of Mikel Serone

Washington D.C., Tilted Kilt Pub & Eatery, United States “Duke, honey, let’s all just go hom

Living Things at Tiger Strikes Asteroid – Greenville, Greenville

“Living Things” by Hannah Chalew, Michael Evans, Manuel Alejandro Rodríguez-Delgado, an