Fakewhale Meets Domenico Romeo: On Modularity, Meaning, and Multiform Practice

We’ve been closely following the work of Domenico Romeo with great interest. As an artist, designer, and art director, he has spent years moving fluidly across visual art, fashion, sculpture, and symbolic writing, developing a personal language that is both ever-evolving and deeply coherent.

His multidisciplinary practice takes shape through three distinct but interconnected identities: Domenico Romeo the artist, the graphic design lab Metaprogresso, and the fluid project space Avamposto Progressivo.

In this interview with FakeWhale, we wanted to explore the heart of his creative process, the symbolic tension running through his work, and how his modular systems relate to space and contemporary identity

Domenico Romeo: My practice is based on the research and production of systems composed of finite elements that, when combined, generate infinite forms. Initially, I focused on creating a cryptic sign-based alphabet, which I reproduced two-dimensionally on various surfaces. Over time, this language became increasingly abstract, allowing form to evolve freely, until I no longer felt the need to continue with two-dimensional painting.

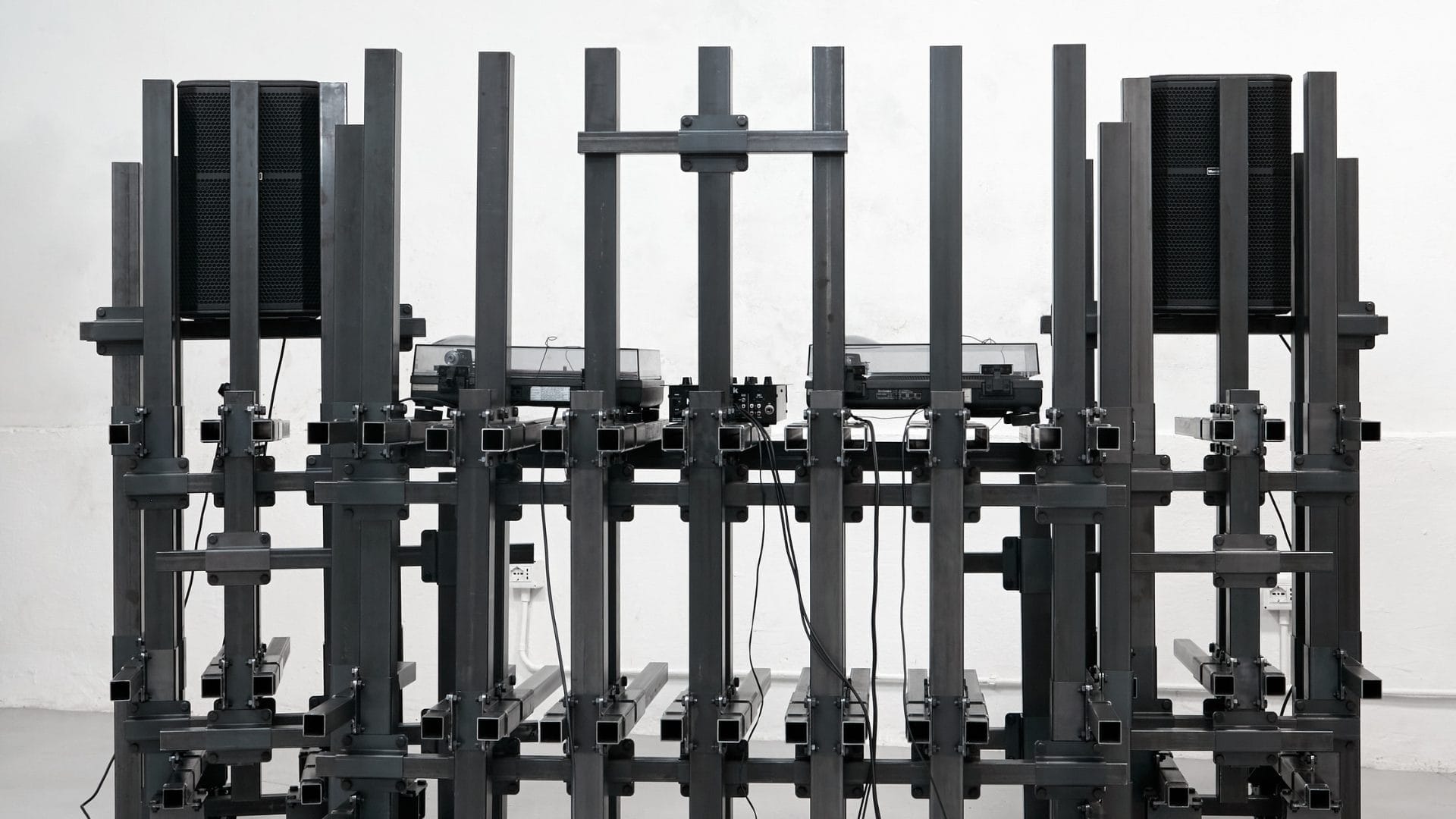

That’s when I felt the urge to engage with space: the material changed, as did the design process and the generative act of the work. But at the core, it remained a modular system of finite elements. The repeating units are iron rods, progressively cut from 50 cm to 400 cm. Horizontal rods have a square section of 4×4 cm, vertical ones 6×6 cm. Diagonals are not included. The joints , also made of iron and designed by me, play a fundamental role in this language: they connect the rods in various ways, making the structures self-supporting. At present, there are around ten different joint types.

This systemic approach ensures a coherent and linear evolution of the practice, although it’s precisely incoherence, understood as radical change, and therefore growth, that I truly aspire to.

We move toward something, we mature, we evolve, but we will always remain irreparably imperfect.

The exhibition guided viewers along a suggested path: from the darkness of a forest of columns to the light of the top floor, where the main structure could evoke an altar with organ pipes, or a cathedral. A precise experience, a “finished” project that left little room for ambiguity. No crisis, no doubt.

The daily dedication to assembling and disassembling these structures is comparable to the obsessive repetition of a solitary prayer. A personal, disciplined ritual, performed every day and completed only when it comes into contact with the outside, with those who choose to interact, to discover, to participate in the “mystery.”

During the first site visit, I register dimensional and atmospheric inputs; it’s usually during the second visit that the emotional spark occurs — the one that helps me understand my position within the dialogue with the space. From that spark emerges a sensation, which becomes a doubt, then a reaction, gradually taking on body and matter.

In this process, considering the spatial experience of the viewer is essential, to ensure the work is precise in expressing what I intend.

A clear example is EAT, a show I inaugurated at Marsèll Paradise in Milan in October 2023.. The gallery presented itself as a long and narrow space. At the time, I was deeply interested in infrastructures: bridges, aqueducts, dams. I immediately thought of a sloped car ramp, as if, at the end of the tunnel, you could drive back up.

However, a visit to the San Nicola Stadium in Bari, designed by Renzo Piano for the 1990 World Cup, proved decisive. Finding myself completely alone inside, I felt an explosive void radiating from the stands. I realized what I was experiencing, besides being deeply personal, was rare, and deserved to be shared.

Back in Milan, a subsequent visit to the gallery revealed the presence of a small storage room accessible through a hidden door, located at the exact opposite end from the entrance. That discovery took root in my mind and enabled the fusion of the feeling I had in Bari with the project in progress.

A thin membrane, filled with compressed air, became the ideal synthesis of that “active void.” The storage room housed a large inflatable pink PVC installation, compressed within it. It was revealed to the viewer only at the end of the austere corridor. A pink light seeped from the door, cutting through the darkness and identifying the destination. The breathing of the blob, amplified by an audio system, heightened the suspense of the journey.

A benevolent virus grows on the margins, and there it chooses to remain. It seems indifferent to the spotlight of the “main stage,” which is free to be occupied by anyone who wants it.

I admit it took time to fully grasp his creative approach: it was radically new, far from the traditional dynamics of fashion. At first, it might have seemed arbitrary. But once I understood his subversive gesture, I embraced the vision — even if it was distant from my aesthetic and cultural codes.

It was an exercise in personal growth that opened my eyes to new horizons. I contributed to the construction of the image and philosophy of a brand that disrupted traditional fashion dynamics.

I never wore Off-White, and Virgil stated this as early as 2016 in an interview: “My team doesn’t wear Off-White,” back when the team could still be counted on one hand. It was his way of saying the clothing wasn’t the point.

The brand was a “space of experimentation” open to all artistic practices, capturing the desire of a new generation to transcend disciplinary boundaries.

Personally, I’ve always tried to break down walls, aesthetic, moral, ideological , to create new, broader scenarios. Virgil and Off-White gave me the chance to put all of that into practice.

With the move to three-dimensional work, my approach to performance design also changed. Starting from the concept, I imagine installations that can express the narrative’s mood, always considering the space in which the action takes place. Without ever slipping into set design, I adapt my language to best accommodate music and bodies on stage.

Painting also changes when it’s live: it becomes frantic, an hysterical dance, almost a fight with the canvas. In those 50 minutes of action, music influences my emotional state and, consequently, the final result. When the performance instead relates directly to the installation, my focus shifts more toward the stage than the work itself.

Cold Still was the first performance created within my studio space. The “storage” became the stage for the first act, while the “main room” hosted the other two. The installations depicted a post-apocalyptic scenario: a semi-destroyed tower stood among rubble and severed electrical cables.

fakewhale

Founded in 2021, Fakewhale advocates the digital art market's evolution. Viewing NFT technology as a container for art, and leveraging the expansive scope of digital culture, Fakewhale strives to shape a new ecosystem in which art and technology become the starting point, rather than the final destination.

You may also like

Refik Anadol: Deciphering Machine Dreams

Art has always been humanity’s conduit to understanding the enigma of existence, our dreams, a

Why I Destroy my Art: Fakewhale in Conversation with Francesco De Prezzo

– “Dear M, good paintings go to galleries, but bad paintings end up everywhere.” W

Nestor Siré, CubaCreativa [PC Gamer], “TOKAS Creator-in-Residence 2024,” Tokyo Arts and Space Hongo

“CUBACREATIVA [PC GAMER]” by Nestor Siré, curated by TOKAS, at Tokyo Arts and Space Hon