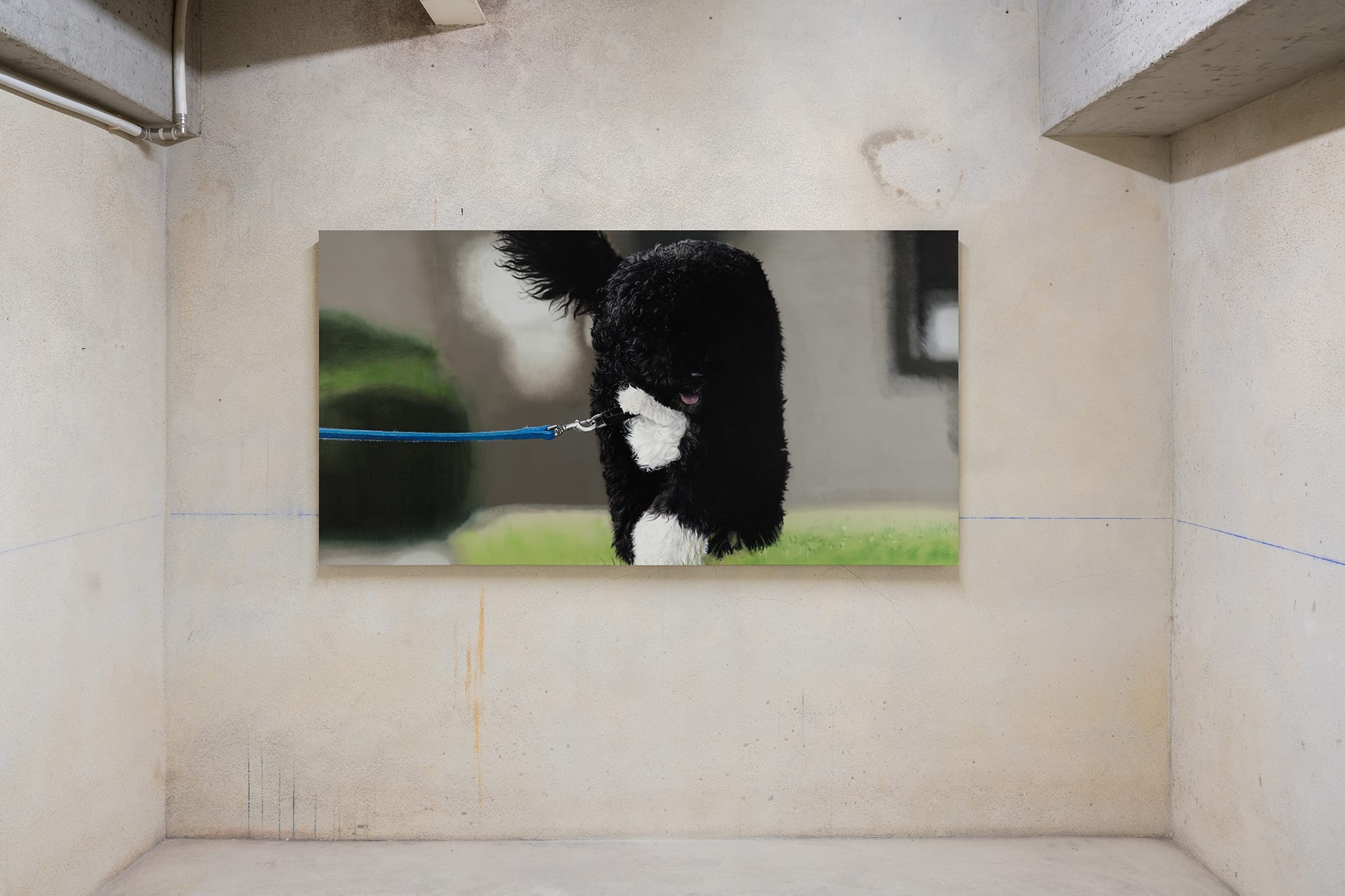

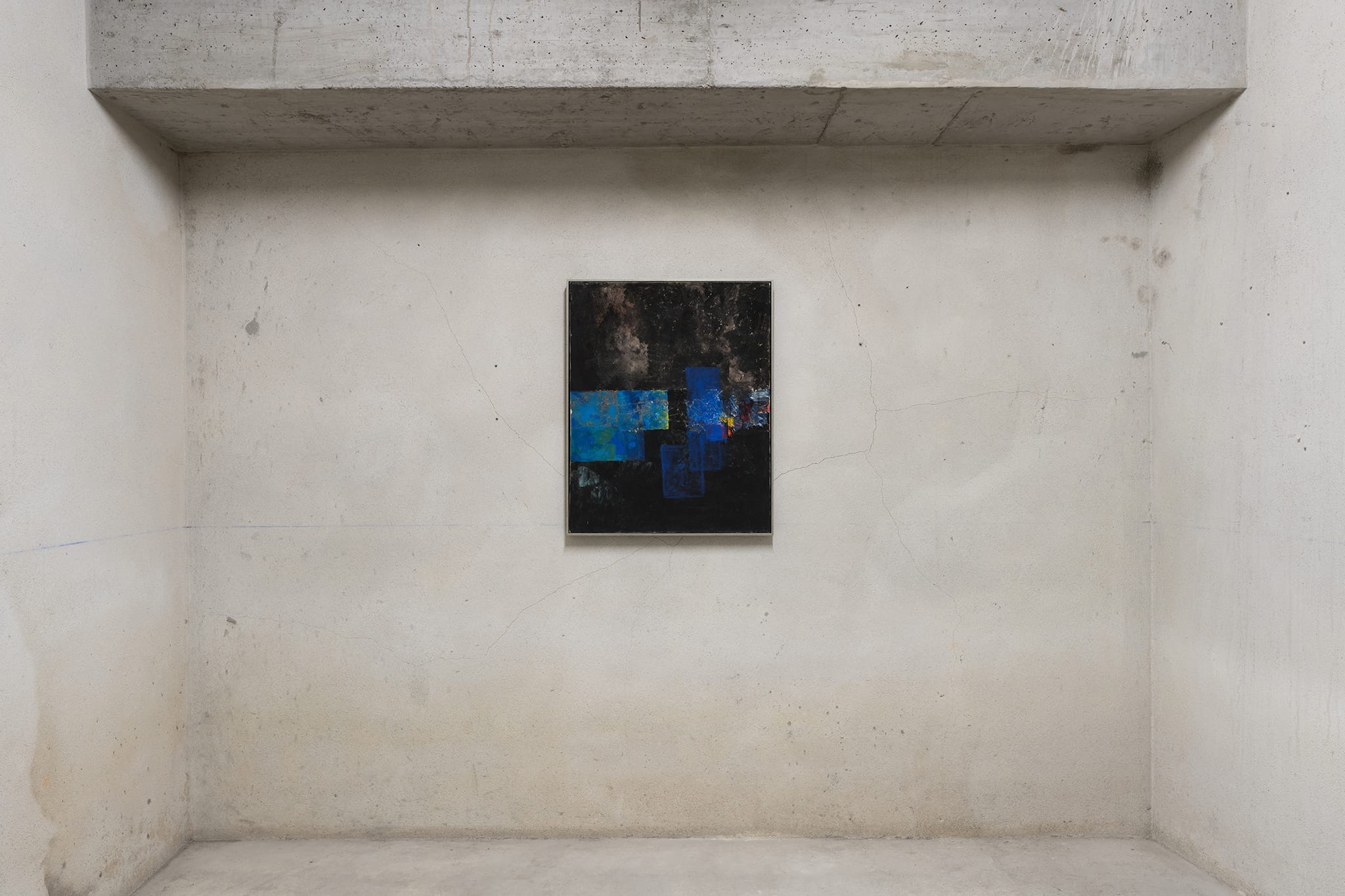

Diogo Pinto, Diplomacia at Belo Campo – Galeria Francisco Fino, Lisbon

Diplomacia by Diogo Pinto at Belo Campo – Galeria Francisco Fino, Lisbon, 24.01.2025 – 07.03.2025.

The existence of a backstage (background) presupposes a centerstage (front), something presented in the foreground that requires no in-depth knowledge of secret movements or plans taking place behind-the-scenes. In Diplomacia, Diogo Pinto presents artefacts of diversion tactics as placeholders for stories of affection, politics and diplomacy between Portugal and the USA. I. Lajes and affections There is, between Portugal and the United States of America, an emotional and geographical love story. The connection’s offspring emerges in 1949, in the middle of the Atlantic ocean between the two nations: Lajes Air Base, pride of Terceira Island in the Azores, and custodial landmark of diplomacy. Like many firstborns throughout History, the Air Base had the intended appeasing effect of diluting the severity of its guardians (many) transgressions. As the national contribution to the founding of NATO, the Base also inflated—in the sensitive decades of early Portuguese dictatorship—the diplomatic, military and strategic importance of Portugal due to being the only point of refuge in the ocean between the continents during the initial escalations of tension between the US and the USSR. For the sake of smooth operations and management of sensibilities, relations between the North American government and the President of the Council of Ministers (Portuguese dictator Salazar) tightened, and Portugal was guaranteed sovereignty over East Timor (after a brief occupation by Japan) and non-intervention in the maintenance of the Portuguese colonial empire project in exchange for the loving Base.

Lajes remained, in the image of its creators, as proof of the ideological sacrifices made by great pragmatists; there are dictatorships and dictatorships, regimes and regimes, and tight relations. When thinking of the political tightening of those decades, consider also of the liaison brought about by this special corridor between the Portuguese coast and that of the USA, and the lines drawn straight across the Atlantic on world maps (how one imagines lengthy and slow journeys were represented before our time of excess): on these trips one magazine, one fashion, one aesthetic arrived in Portugal at a time.

A natural absorption of post-war American prosperity—prescribed in micro-doses, like any foreign press or democratic culture had to be—was intuitive through mainland Portugal, the islands and even the colonies; the latter, called provinces and never ‘colonies’ by the Americans at Estado Novo’s prolonged insistence, were the main transgression to which one turns a blind eye in the name of keeping partnerships functional. In this case, American ceased appeals for the right to self-determination of the countries colonised by Portugal, and a precedent was set. American pragmatism carried on until the election of JFK (with his anti-colonial stance) in 1961, causing the first significant change of US sentiment towards the Portuguese empire consolidation plan. The pressure for Portugal to decolonise led to discord between the two countries in the United Nations, veiled threats, an embargo of weapons aimed at suppressing liberation movements in Angola, and a time of great distress for dictator Salazar; but the American scolding quickly reverted to its circumspect position of Pre-Kennedy times, for predictable reasons: the Air Base, indispensable to the US, and the inevitable negotiations of the terms of its use (whose concession contract bended to Salazar’s will). Until the 1970s, the US political and diplomatic posture on colonial Portugal was ruled by the Lajes Base and its logistical and emotional issues. II. Apollo In the Summer of 1974, shortly after the Carnation Revolution, an old British Royal Navy ship from WWII docked in Lisbon. The crew was made up of young Americans in vaguely nautical uniforms. The ship, now called Apollo, went from port to port promising free concerts by its resident band, The Apollo Stars, for the locals; sometimes, as the ship approached the docks, the band would already be playing on deck alongside the dance group that completed the show.

This staging, conceived by the band’s founder and leader of the fleet (Apollo and two other ships), was intended to ensure that concerts were scheduled before the crew even went ashore. Part of an organisation called Sea Org, the crew and ship had been roaming the ocean full-time since 1967 because the Sea Org had already been banned from several countries. The Apollo was, after all, the mobile headquarters of L. Ron Hubbard and the Church of Scientology, and The Apollo Stars—comprised of high-ranking Scientologists—one of the Church’s recruitment projects disguised as a personal endeavour. L. Ron, also called “The Source”, had moved the headquarters of the Church of Scientology out of the US after several problems with the IRS and the American Food Drug Administration. Upon arriving in Lisbon, Hubbard rented a theatre and coordinated the ill-tempered recording of The Apollo Stars’ album Power of Source, with his own compositions, in torturously long sessions (the last song on the album, “Meu Querido Portugal” [My Dear Portugal], pays homage to the country that best had welcomed them up to that point). III. Procrastination Towards the end of 1975’s Verão Quente [Hot Summer—high voltage political period], PREC’s fifth provisional government took office. On the morning of August 30, a memorandum was sent to the White House in Washington conveying the views of the Deputy Director of the CIA on the political situation in Portugal.

He had received the situation from Frank Carlucci, the American ambassador in Portugal, and the information was now going up the chain of command to the recipient, Secretary of State Henry Kissinger. Kissinger was agitated by the situation in Portugal and convinced of the supposed imminence of a Soviet-leaning communist regime. “Pentagon sees threat in Red Portugal”, 2 August 1975, New York Times article “RED THREAT IN PORTUGAL”, 11 August 1975, TIME magazine cover “PORTUGAL: Western Europe’s First Communist Country?”, 11 August 1975, TIME magazine article The Secretary of State’s nervousness was also fuelled by the poor quality of the intelligence passed on by CIA agents in Portugal before, during and after 25 April: they were taken by surprise, failed to understand the Revolution, and continued to do so for many months. As the agents were unable to clarify the resolutely historical momentum of the Revolution to the State Department it fell to Carlucci, who had arrived in Lisbon in December 1974, to organise facts and compile narratives; and it was his responsibility, as it is for ambassadors, to figure out the minutia of a culture in the unique moment of celebration, conflict and uncertainty that came with its newfound freedom and try to understand it on an intimate, atomic level, so as not to make the mistake of disrespecting or underestimating it—especially when a US Secretary of State seemed hopelessly drawn to intervene.

The solemn and very secret memorandum from CIA’s deputy director V. Walters to Kissinger insisted on Carlucci’s strategy: to appease the Secretary of State through assurance that Portugal would not become a communist country, and to trust in the (young) democratic process that Portuguese society was going through (certain expectations surrounded the politically moderate Group of Nine). Carlucci was, among relevant agents, a meaningful advocate of non-intervention by the US military in Portugal during PREC (although he didn’t commit as strongly against backstage politics). At the end of the memo, Walters expresses impatience over the moderate factions’ lack of violent action against the communists which, he writes, could only be justified by the “endless Portuguese capacity for procrastination”. IV. Red Threat But it is in TIME magazine, dated 11 August 1975, that the ‘Red Threat’ looming over Portugal as conjectured by the State Department is best exemplified.

It is not, however, in the long article dedicated to the Portuguese political state of affairs (“PORTUGAL: Western Europe’s First Communist Country?”)—which began by announcing that the revolution’s red carnations from the previous year, so vibrant and promising, were now wilted carnations: faded by the threat of leftist extremism and Soviet sympathy. It is instead the cover illustration that immediately hints at the piece’s intention: Otelo Saraiva de Carvalho, Vasco Gonçalves and Costa Gomes are represented as floating heads and necks. Their portraits, stylised from photographs, are surrounded by a yellow sickle over a red background. The composition is reminiscent of Hollywood film posters from other decades; and aludes, most importantly, to the regimented representations typical of the Socialist Realism of USSR propaganda, with whom the US had long been engaged in an aesthetic dispute. Since its inception in 1947 that the CIA included art and culture as a weapon of ideological warfare in its endless list of resources and strategies. The concern and attention devoted to the interpretation of visual elements during the Cold War deliberately forged ideological links that would prove almost unmovable. Consider the relentless visual transformation in Portugal in the aftermath of 25 April, such as the profusion of posters or the vigorous character of mural interventions, reclaiming public space. This extension of democratic demonstration must have greatly inconvenienced the US State Department; popular attempts to depict workers’ revolts and land reform (The land to those who work it / if the working class produces everything, everything belongs to it) were notoriously figurative and, from such an aesthetic (or any kind of ‘realism’), the US wanted nothing but distance. Secretly the CIA had been, since its foundation and for several decades, supporting the exhibition and circulation of modern American art, specifically examples of a practice that came to be known as Abstract Expressionism, through elaborate schemes of indirect funding. V. Cultural Diplomacy In 1946, shortly before the birth of the Air Base, the State Department began a cultural diplomacy program meant to publicise new modern art produced in the US through touring exhibitions (Advancing American Art) that became controversial in its own country.

Although it was intended to establish and promote the freedom of expression enjoyed by artists in the US—highlighting the contrast with certain other colder approaches to cultural creation—the featured artworks were not well received, and the most conservative section of Congress considered the paintings un-American, accusing the artists of enacting a communism-driven plot to embarrass the US (it was the McCarthy era of incessant accusations and abundant paranoia). Funding was withdrawn and the exhibition’s further travel plans were quickly cancelled.

The mismatch between the State Department’s cultural policies and the reaction of leaders themselves (“If that’s art I’m a Hottentot!”) exposed the program’s fragility: the US was not, after all, modern or culturally developed enough for the new chapter of artistic sophistication, apparently free of ideological constraints, that the State Department had devised. Something had to be done to counter the public image of US cultural small-mindedness after the Advancing American Art fiasco: to legitimise and promote expressions of this desired modernity, meant to illustrate ideological opposition with enemies, effective strategies had to be developed. VI. Un-American At that time, an unusual type of painting began to emerge in dark studios throughout the USA at the hand of (self-proclaimed) solitary men who were firm disbelievers of the government, and even more so of its institutions. Their paintings resulted of an intentional emphasis on the work process and notoriously broke away from any attempt at representing life or reality (this decision is historically regarded as a reaction to the unspeakable atrocities of WWII and the role of images at breaking point moments).

This practice of gestural and intuitive painting, called Abstract Expressionism, became expediently and conveniently associated with ideas of modernity, spirituality and intellectual freedom; and its precursors (Rothko, Pollock, Francis, Newman, Motherwell, de Kooning) welcomed a semi-prophetic status (as visionaries) perpetuated by the radical nature of their proposed positions and processes. A few years later and despite initial widespread apprehension, the success of Abstract Expressionism irreversibly saturated the collective unconscious. International exhibitions and continued support from other cultural agents contributed significantly to the consecration of the movement; the cultural organisation Congress for Cultural Freedom, or CCF, founded in 1950 in Berlin by intellectuals and which at its peak was present in more than 50 countries, stands out as the movement’s major promoter. It was also Abstract Expressionism’s meteoric rise that cemented New York (and therefore the USA) as the West’s uncontested artistic and cultural centre. The movement’s mystique remained strong until the 1970s, by which time it was already an undisputed national symbol. VII. C.I.A. In 1967 it was revealed that the Congress for Cultural Freedom—parent organisation of some 20 international magazines, sponsor of important international exhibitions and promoter of major collections—was the crucial instrument of a risky and successful CIA covert operation in the context of the Cold War.

Accounting for the reactions to the modern art exhibition in 1947, the prevalence of Abstract Expressionism seems less mysterious or improbable when considering the impunity of the CIA’s sections dedicated to propaganda: unbeknownst to the artists, abstraction was weaponised as a symbol of the alleged triumph of freedom of thought/expression in the West, endorsed in the media by an intellectual class who contributed to the success of the operation (whether or not they were aware of the CCF’s implications). The aim was to highlight artistic and cultural production that could be framed in total opposition to the Soviet Union’s cultural policy: the freer, less figurative and more famous the expression of American art, the more absurdly strict and cruel Soviet Socialist Realism (and, therefore, its ideology) was perceived to be. VIII. Rumours When it prepared to dock in Funchal in October 1974, after wrapping up the recording of Power of Source in Lisbon, the Apollo failed to receive the messages sent by the Sea Org member who had stayed ashore since the ship’s last passage in Funchal, and who was now trying to alert the ship to the increasingly hostile atmosphere on the island. The ship had always presented itself to the Portuguese and Spanish naval authorities as an asset from a wealthy consultancy firm, but its rusty and worn-out state didn’t match the story. Distrust had grown for the military vessel, full of Americans with little justification for their frequent visits to Portuguese ports and unconvincing backstories.

Naturally, there was already a persistent rumour that the ship was actually operated by the CIA and had arrived with the intention of spying on and intervening in the military and political processes taking place in Portugal (it is no wonder the rumour had so much adherence: if the obsession and extent of the CIA’s operations were as far-reaching as to push the success of expressionist painting movements for the purposes of ideological warfare, then a dubious jazz band on an old ship was, in comparison, a derisory undertaking).

After docking, a crowd gathered in the harbour; shortly after, the increasingly aggressive mob threw the Apollo crew’s motorcycles overboard. Watching the scene unfold, the Sea Org members who were ashore rushed back on board; the crowd threw stones and bottles at the ship’s hull, shouting ‘CIA! CIA! CIA!’. The crew, confused, returned the chant—and when the dispute didn’t show signs of calming down, proceeded to throw stones back at the crowd (L. Ron Hubbard was allegedly taking photos of the protesters while shouting the word ‘COMUNISTA!’ [COMMUNIST] through a megaphone). Tempers did not subside, and with confusion on board and no clear leadership, the ship fled the harbour. Shortly afterwards, out of remaining friendly harbours, the Church of Scientology gave up the fleet and re-established its headquarters in the USA. It is not clear whether the crew understood, that late afternoon in Funchal, the chanting of the angry crowd. IX. Several Lives Vasco Futscher Pereira (1922 – 1984), renowned diplomat and minister, began painting in 1979 in New York where he was a representative at the UN. In 2017, when his family decided to donate the diplomat’s estate to the Historical-Diplomatic Archive of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, several highlights of his remarkable career came to light: as ambassador and diplomatic representative he was in Malawi, Germany, Brazil and the USA, among many other places; he played an important role in the conversations about the situation in Timor; as ambassador in Bonn he rushed to declare support for the Junta de Salvação Nacional [National Salvation Board] on 26 April 1974; he was even Minister of Foreign Affairs. His love of writing, attested to by his tendency to write long narrative telegrams, is well documented in his estate. But not his passion for painting, which was certainly stimulated by his diplomatic stays in the USA and the facilitated access to modern art—Futscher Pereira frequented circles which, as we have seen, favoured the exhibition and circulation of Abstract Expressionist paintings. When he presented his expressionism-influenced paintings at the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation in 1984, the initial contours of the movement had already dissipated in the USA (Ab. Ex. was, of course, specific to its moment).

Abstract Expressionism evolved to obtain another dimension that still exists today: one that is not as politically charged (at least, not in the CIA way), and instead places far more importance in the joyous pleasure of a painting practice that is carefree—unconcerned with life’s heavyweights. In the catalogue for the solo exhibition at Gulbenkian, the politician and writer António Barreto writes that Futscher Pereira was “simmering in soft heat, between embassies and dispatches” and the exhibition of the thirty-one paintings “is an explosion”, as if he wanted to “live several lives in a single exhibition”. In the comprehensive 2017 article on the donation of the estate, Futscher Pereira’s daughter Vera says that in the documents “one realises that being a diplomat is above all about describing and analysing what is happening in countries” and that organising her father’s papers and folders “was a behind-the-scenes look at a profession that is so secretive”. The secrecy, charisma, cool and monumental sense of responsibility required in diplomatic positions are inexplicably matched by the sort of sensitivity necessary to make paintings. X. Diversion tactics Tactics of ‘Diversion’, as in ‘Fun’ Manoeuvres, as in ‘things concocted to distract the audience from the mess taking place backstage’. Sometimes the mess is centerstage, taking place in broad daylight, on a deck, or in front of millions; in this scenario, maybe roles are inverted and one dreams that perhaps, at least backstage, someone or something with a backbone is making informed decisions. The fascination with diplomacy is never-ending; what secrets do great diplomats and statespeople hide behind the grey cool demeanour we’ve been used to expect? What are their diversion tactics diverting us from? One can only hope their biggest secret is a passion for painting, because that we can understand.

Mariana Tilly

fakewhale

Founded in 2021, Fakewhale advocates the digital art market's evolution. Viewing NFT technology as a container for art, and leveraging the expansive scope of digital culture, Fakewhale strives to shape a new ecosystem in which art and technology become the starting point, rather than the final destination.

You may also like

The Future Perfect: Ben Edmunds’ Chromatic Adventure

Upon entering Ben Edmunds‘ exhibition titled “The Future Perfect” at the L21 Galle

Michael Sailstorfer, ELEKTROSEX at TICK TACK, Antwerpen

“ELEKTROSEX” by Michael Sailstorfer, at Tick Tack in Antwerp, Belgium, March 1 – April

Programmed Bodies: Contemporary Performance Between Aesthetics and Technological Embodiment

If one tries to access the website www.liminal.contact today, what appears on the blank page of our