Chris Burden: The Edge Where Art Meets Risk

Some artists work within the frame. Others break it.

Chris Burden made it dangerous to even stand near it.

In a time when art flirted with theory and dematerialization, Burden introduced something else entirely: consequence. His work didn’t ask to be interpreted, it forced you to respond. First with the body, later through systems and machines, Burden constructed situations where control was fragile and meaning couldn’t be separated from risk.

There was no illusion. No metaphor. Just action, exposure, and the strange intimacy of witnessing something real, too real.

This is not a retrospective out of nostalgia. It’s a return to the fault line where art stops being safe.And a reminder that some thresholds, once crossed, can’t be undone.

From Anatomy to Performance: The Formative Years

Chris Burden was born in 1946 in Boston, Massachusetts, and from the very beginning, his path was shaped by a deep tension between structure and disintegration, science and art, control and risk. The son of an engineer and a biologist, he spent his early years between America and Europe. At age 12, during a family stay in Italy, he suffered a severe motorcycle accident, an incident that would prove formative not only physically but symbolically. It marked the first time his body was opened, stitched, and reconstructed, an experience that profoundly informed his later explorations of vulnerability and endurance.

His academic journey mirrored this duality. Burden studied physics and architecture at Pomona College before earning an MFA in Fine Art from the University of California, Irvine. It was at UC Irvine, in the post-1968 atmosphere of anti-institutional experimentation, that Burden encountered figures such as Robert Irwin and Allan Kaprow, and discovered a form of art liberated from the object, art that could inhabit gesture, action, and ephemeral events.

These formative years were characterized by a growing disillusionment with traditional visual language and an increasing fascination with conceptual art, minimalism, and the legacy of the happening. Yet while many of his contemporaries gravitated toward cerebral or theoretical approaches, Burden became increasingly fixated on the body as the origin point of artistic truth. Not an idealized or abstract body, but a real one, fragile, vulnerable, exposed.

In 1971, he performed Five Day Locker Piece, one of his earliest and most intense works, confining himself for five full days in a student locker without moving. This claustrophobic and extreme gesture reduced the individual to a pure state of resistance. It was the beginning of a new kind of art, one that did not represent, but happened; that did not depict, but exposed.

Burden’s education was not merely academic, it was existential. And from that point forward, he would follow one of the most radical and uncompromising trajectories in postwar American art.

The Body as Extreme Instrument: Performances of the 1970s

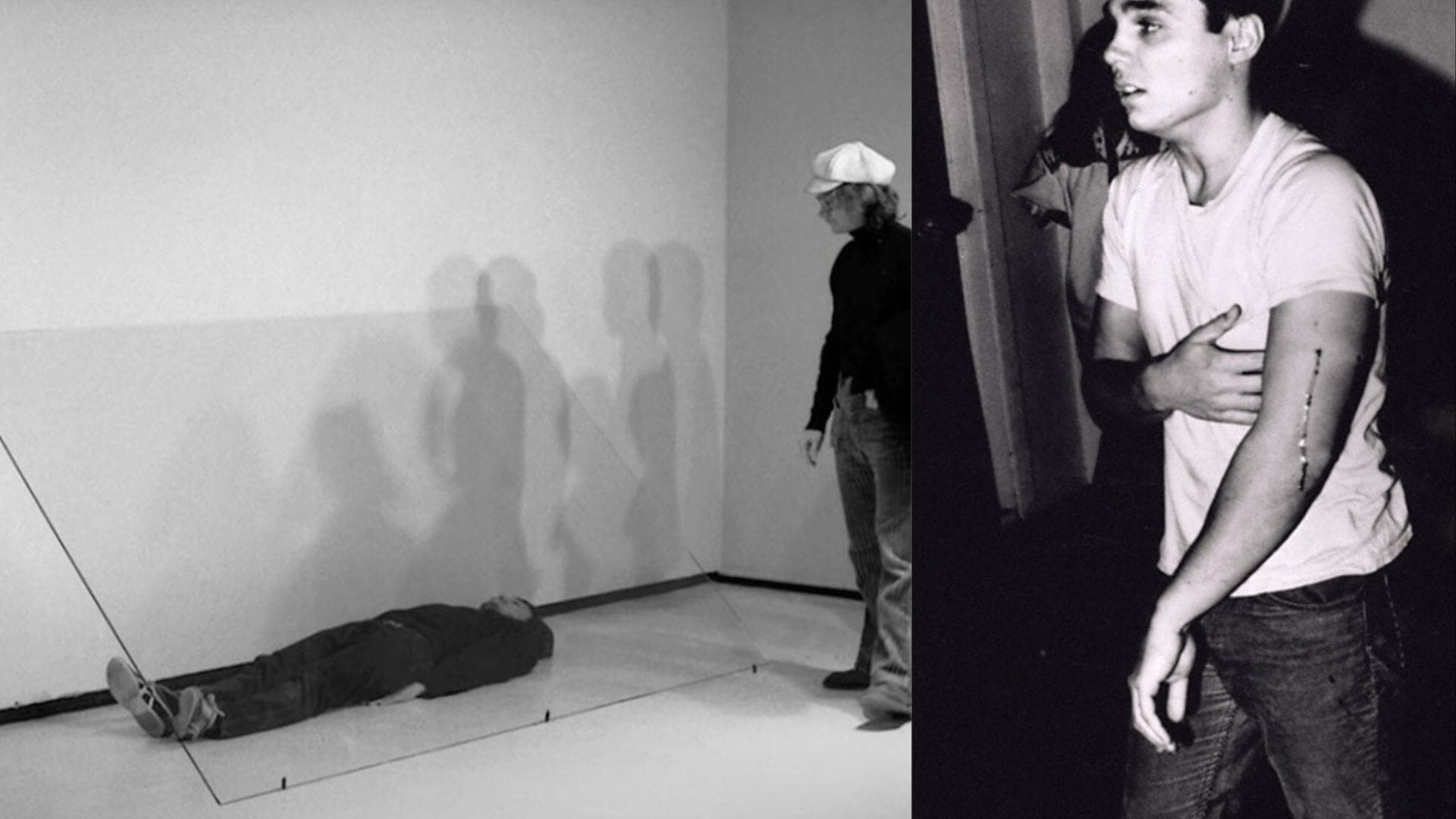

In the early 1970s, Chris Burden redefined the limits of art by turning his own body into both subject and medium. His performances from this period are among the most radical in contemporary art history, not because they shock, but because they reveal something disturbingly precise about vulnerability, power, and the thin line between presence and disappearance.

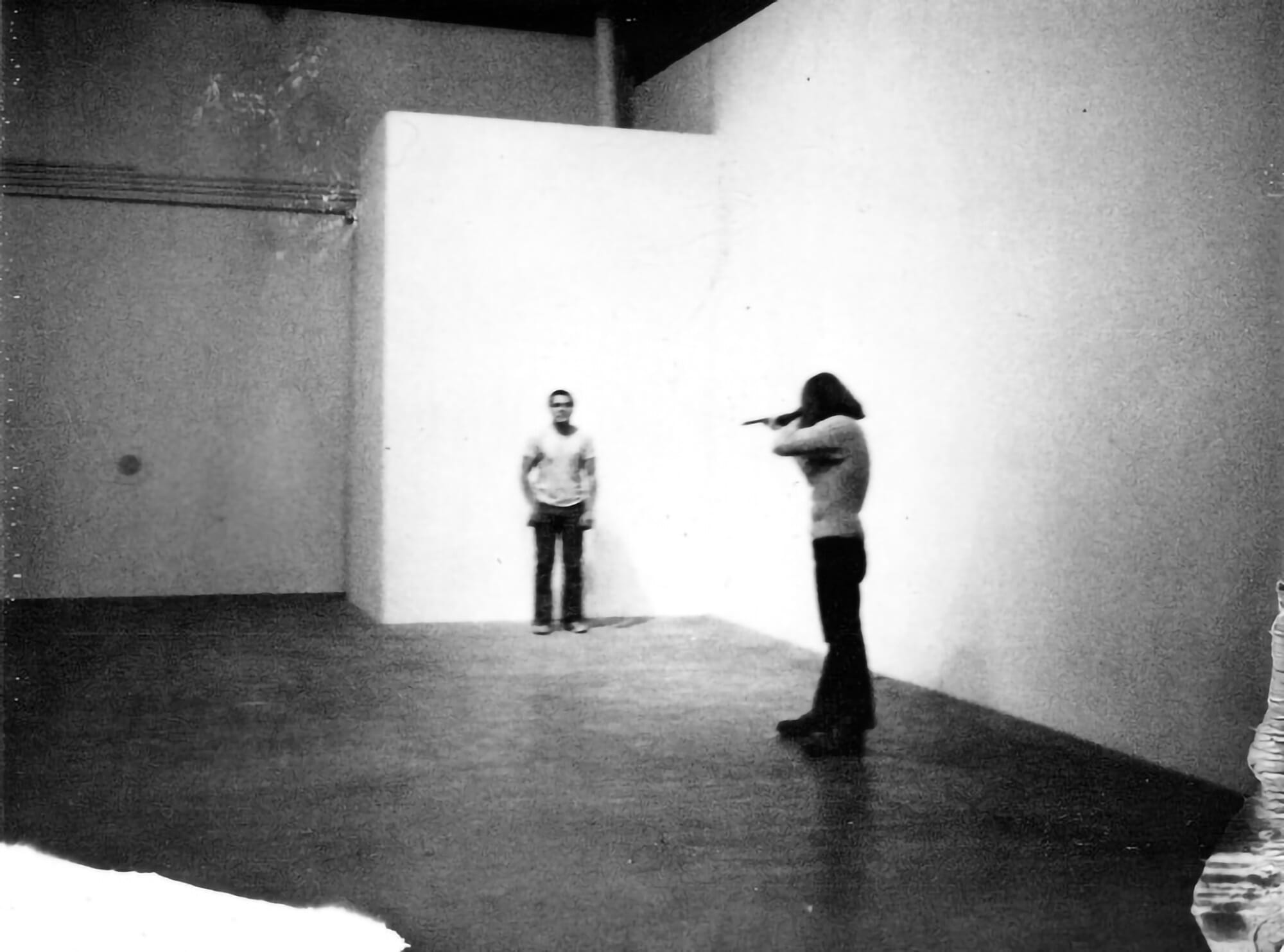

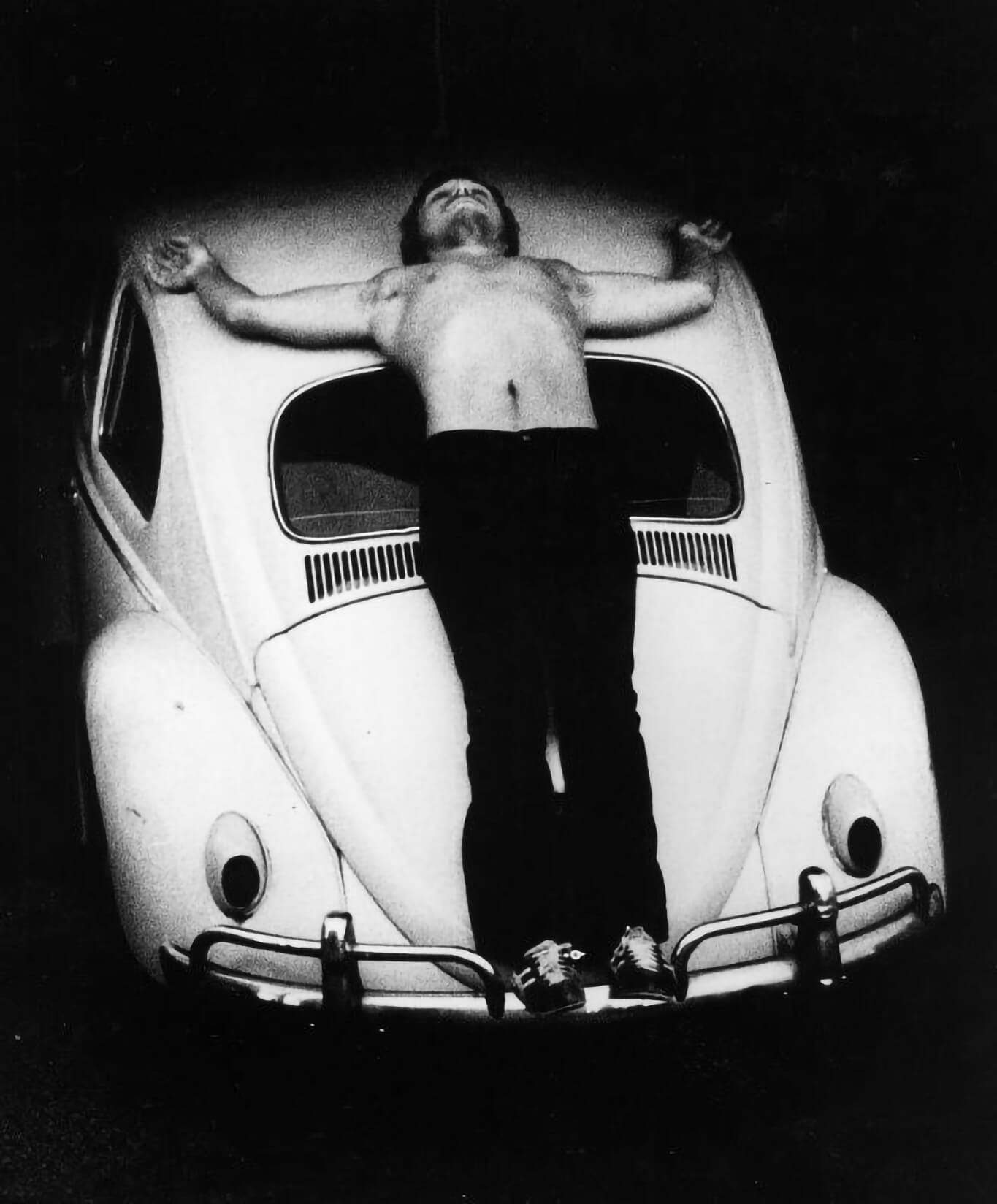

Works such as Shoot (1971), in which Burden was shot in the arm with a .22 rifle, or Trans-fixed (1974), where he was crucified onto a Volkswagen Beetle, are not theatrical stunts. They are rigorous experiments in perception, ethics, and authorship. Burden didn’t stage violence, he submitted to it, transforming personal risk into a space of collective reflection. His performances became live thresholds, where art intersected with life, pain, and danger without mediation.

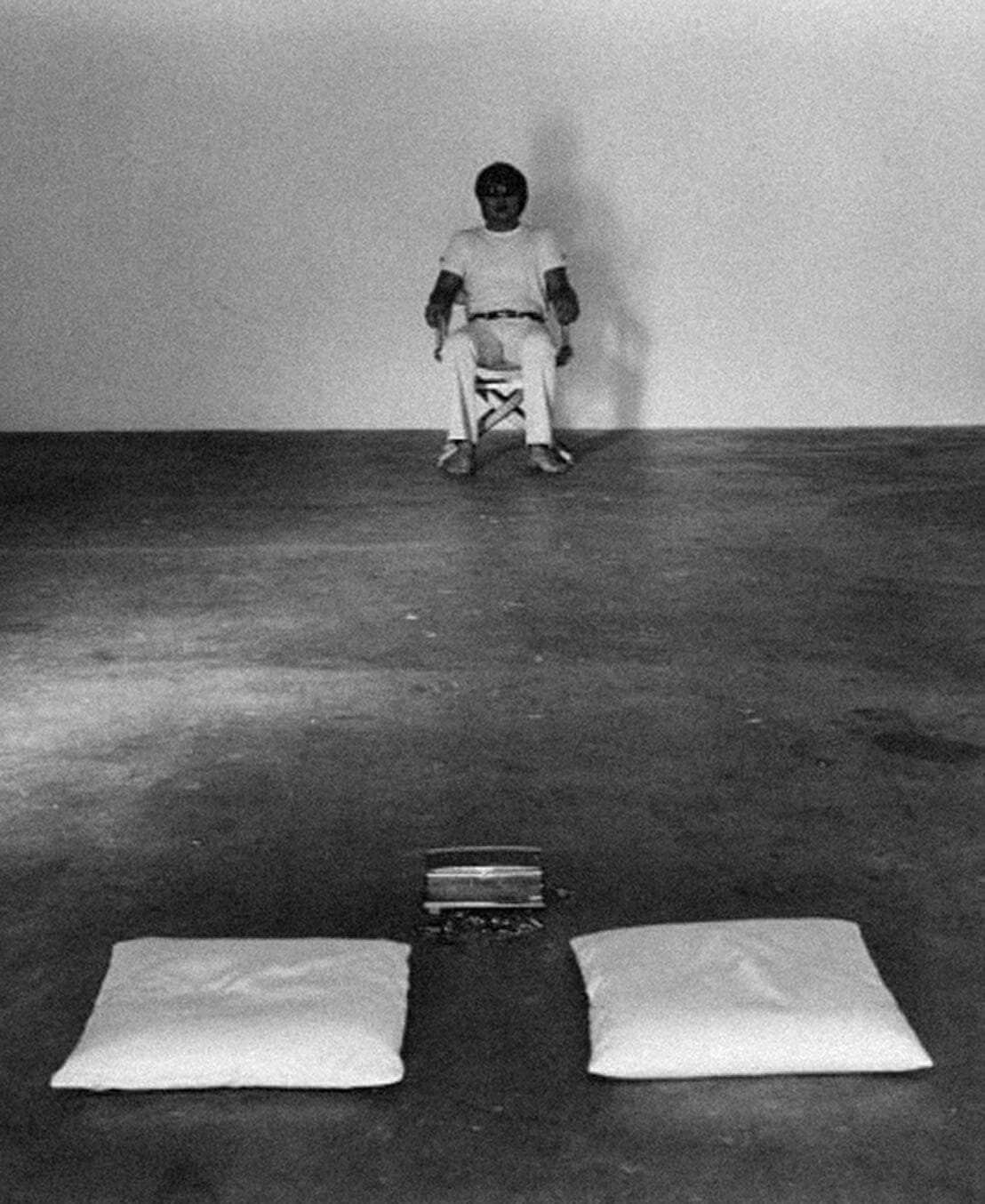

Rather than dramatize suffering, Burden operated with forensic clarity. In Five Day Locker Piece, he confined himself in a tiny school locker for five days without food or movement, creating a quiet but oppressive meditation on endurance, isolation, and institutional space. In Do You Believe in Television?, he locked himself in a gallery for hours, communicating with the outside world only through live TV. These works stripped performance down to its essence: time, space, presence, and the implicit complicity of the viewer.

The 1970s for Burden were not a season of spectacle but a field of inquiry. He used his body like a scalpel to dissect the political and psychological mechanisms of control. In an era scarred by the Vietnam War and the trauma of state violence, Burden’s work echoed a broader cultural unease. But rather than protest, he embodied the contradictions of his time.

He didn’t scream. He acted, and let the silence carry the weight.

The Viewer as Accomplice: Power, Control, and Responsibility

In many of Chris Burden’s performances, the central figure isn’t the artist, it’s the viewer. The audience is never merely a spectator: it is a witness, often a silent accomplice, sometimes even a surrogate perpetrator. His actions don’t end in the physical gesture; they unfold in the ethical ambiguity they provoke: What are you willing to tolerate? How far can you go just by watching and doing nothing?

In Shoot (1971), Burden is shot at close range by a friend using a .22 caliber rifle. The audience, whether physically present or imagined, is immediately drawn into a moral dilemma. Burden doesn’t simply critique violence; he stages it. He doesn’t condemn it; he renders it aesthetic, factual, social, leaving others to legitimize or reject it. The work becomes a system of psychological and ethical forces, and the true subject isn’t the bullet, but the reaction it demands.

Power is a recurring theme in Burden’s practice. But he doesn’t discuss power, he enacts it. In Deadman (1972), he lies motionless under a tarp on the pavement, surrounded by roadside flares, simulating a corpse. The audience, like an invisible authority, must decide what is real, what is performance, and what is a trap. The work implicates not only the idea of institutional force, but also the role of art as a destabilizing ritual. It’s an American gesture, born in a culture where the line between performance and crime is dangerously thin.

Burden pushes responsibility beyond aesthetics, compelling the audience to reckon with its own role in cultural and political systems. In the shadow of the Vietnam War, Watergate, and a collapsing trust in authority, his work functions like a micro-scale re-enactment of larger societal logics: obedience, exposure, punishment.

Over time, Burden refines this dynamic. The physical risk subsides, but the paradox remains. The viewer is still caught in the crossfire. His later works replace the threat to the body with conceptual traps and psychological tension, but the ethical weight endures.

In the end, Burden flips the script: he’s not the one on trial.

You are.

From Action to Construction: Sculpture as System

By the 1980s, Chris Burden had largely stepped away from body-based performance. Not because he had exhausted the form, but because he had taken it to its absolute limit. The transition to sculpture was not a retreat, it was a continuation. The themes of control, risk, and engineered tension didn’t disappear; they transformed. What was once visceral became mechanical. What was once the body became the system.

Burden began building complex structures powered by motors, pulleys, counterweights, works that often felt like functioning machines or unstable prototypes. The sense of danger remained, but it was now embedded in kinetic energy, potential collapse, or industrial noise. Fragility was no longer a matter of flesh, but of circuitry and torque. As with his performances, Burden’s sculptures didn’t just exist, they operated.

One early emblem of this shift is The Big Wheel (1979), in which a 250cc motorcycle is revved to full speed to spin a massive cast-iron flywheel weighing over 1,200 kilograms. The machine’s velocity is hypnotic and terrifying, capturing, in mechanical form, the same tension between spectacle and threat that once lived in his performances.

Over the following decades, Burden constructed what might be described as a theatre of complexity. A Tale of Two Cities (1981), a sprawling diorama of two imaginary cities at war, complete with trenches, tanks, and scale-model chaos, mirrors geopolitical conflict in miniature. Burden positions himself as a kind of myth-maker-engineer, blending play and prophecy, absurdity and architecture.

In later works like Urban Light (2008) and Metropolis II (2010), Burden reclaims the language of infrastructure and turns it into sculpture. Urban Light, an elegant forest of 202 vintage street lamps installed at LACMA, became an icon of Los Angeles, but also a quiet monument to forgotten civic design. In Metropolis II, over a thousand miniature cars race through an elaborate system of tracks and ramps, creating a city in motion, both exhilarating and exhausting, a dream of modern speed turned dystopian.

Even without his body, Burden continued to construct tension. His sculptures are not static objects; they are systems that pulse, move, hum, and , above all, anticipate failure.

They don’t ask to be admired.

They demand to be watched, closely.

Collaborations, Relationships, Institutions

Despite his reputation as a solitary and uncompromising figure, Chris Burden cultivated deep relationships, with individuals, with institutions, and with the very mechanisms he seemed to challenge. His career was marked by a subtle choreography of confrontation and negotiation, retreat and reentry, a delicate balance between radical independence and strategic engagement.

One of the most significant personal and artistic relationships in his life was with fellow artist Nancy Rubins, his longtime partner and a major figure in American sculpture. Their practices were distinct yet resonant: both explored mass, tension, and the unpredictable behavior of materials. Sharing a studio and a vision, they helped define a post-industrial American sculptural language, one where chaos and structure are permanently entangled.

Burden’s relationship with art institutions was complex. Early in his career, he was openly skeptical of museums and galleries, refusing invitations and retreating from the art world at a moment when performance art was being assimilated and sanitized. In the 1980s, he deliberately stepped back, choosing to work from his Topanga Canyon studio, an isolated, almost monastic setting where he continued to experiment, out of view but not out of relevance.

Yet Burden never abandoned the idea of public art. Starting in the 2000s, he began producing monumental works designed for civic space. Urban Light (2008), permanently installed at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, stands as both a love letter to the city’s urban memory and a symbol of Burden’s re-engagement with the institutional world on his own terms. Once a provocateur, now a cultural cornerstone, but without compromise.

He also worked closely with galleries such as Gagosian and institutions like the New Museum and MOCA, not simply exhibiting works, but carefully designing the spatial conditions necessary to preserve their original tension. His installations did not adapt to the museum; the museum had to adapt to them. That demand for integrity, spatial, conceptual, moral, was a hallmark of his practice.

Burden’s institutional presence was never about assimilation. It was about timing, scale, and control. He entered spaces not to be embraced, but to transform them.

To remind them, and us, that even within the museum, the machinery of risk can still hum.

fakewhale

Founded in 2021, Fakewhale advocates the digital art market's evolution. Viewing NFT technology as a container for art, and leveraging the expansive scope of digital culture, Fakewhale strives to shape a new ecosystem in which art and technology become the starting point, rather than the final destination.

You may also like

VR Program: Forging New Artistic Frontiers

Sitting at the nexus of contemporary and digital art, Fakewhale presents the Fakewhale VR Program: a

7 Must-See 2024 Venice Biennale Pavilions

Set against the timeless splendor of Venice, the 2024 Biennale emerges as a dynamic showcase of cont

Flēra Bīrmane, FADING at Off-site, Riga

“FADING” by Flēra Bīrmane, curated by Elīna Sproģe and Žanete Liekīte, at Off-site