The Stillness That Burns: Inside the World of Bill Viola

ately we’ve found ourselves drawn to the spaces where time resists compression, where video art moves beyond the screen and into something slower, deeper, almost liturgical. In exploring this terrain, we’re less interested in spectacle than in suspension, in works that don’t impose themselves but unfold quietly over time.

There’s a particular kind of power in images that delay resolution, images that ask us not just to look but to stay. In these gestures, we recognize a different relationship with technology, one where the digital becomes a medium for presence, for memory, for transformation.

As we continue to explore the thresholds between body, image, and perception, we return to the idea that video art at its most essential can still serve as a mirror for the inner self, and a vessel for the invisible. It is within this context that we feel compelled to retrace the path of one of the most emblematic figures in this field, an artist who has turned video into a language of contemplation, ritual, and revelation: Bill Viola.

Sound, Image, and the Architecture of Perception

Before Bill Viola became synonymous with video art, he was a curious boy growing up in Queens, New York, captivated by the immersive worlds of water, sound, and silence. Born in 1951, Viola’s formative memories are filled with sensory intensity, from the deep stillness of a lake he nearly drowned in as a child, to the flickering cathode rays of early television. These moments weren’t just experiences; they were seeds of a visual and existential vocabulary that would later define his artistic language.

Viola studied at Syracuse University in the early 1970s, a place that was, at the time, a rare hub for experimental video. There, he encountered the emerging possibilities of electronic media, studying under avant-garde figures like Jack Nelson and working in the Synapse Video Center. He also immersed himself in sound art, working with composer David Tudor and the group Composers Inside Electronics, a collective that merged experimental music with new media practices.

What distinguished Viola early on wasn’t just his technical skill, but his philosophical sensibility. From the beginning, he approached video not merely as a medium but as a mirror, a way to explore inner states, consciousness, and the ungraspable rhythms of life and death. His interest in perception, duration, and the body emerged less from theory than from a deep engagement with the physical and metaphysical dimensions of lived experience.

In these early years, we already glimpse the contours of Viola’s mature vision: slowness as a radical gesture, the screen as a site of contemplation, and technology not as spectacle but as a portal to transcendence.

Early Works and Radical Experimentation

The early 1970s marked a formative period for Bill Viola, a time of restless experimentation that laid the foundation for a radically personal approach to video. While studying at Syracuse University, one of the few American institutions at the time offering access to video equipment and experimental media programs, Viola became immersed in a creative environment that fused art, sound, and technology. His interests quickly expanded beyond the classroom, he gravitated toward the Synapse Video Center, a space where artists, engineers, and thinkers converged to explore the possibilities of electronic image-making.

It was here that Viola encountered sound as a sculptural medium. Collaborating with avant-garde composer David Tudor, he joined the collective Composers Inside Electronics, a group that performed immersive electronic sound environments across North America and Europe. Their work transformed abandoned buildings, empty pools, and public spaces into resonant ecosystems, part performance, part installation, part meditative ritual. These were not concerts in the traditional sense, but experiences of vibration, disorientation, and presence. Sound became architecture; space became a resonant body.

At the same time, Viola was absorbing the influence of early video pioneers like Nam June Paik and Peter Campus, whose work emphasized the conceptual and psychological dimensions of the moving image. Through these encounters, he began to see video not as a tool of mass communication but as a medium capable of inner revelation, of making visible the thresholds between sensation, perception, and memory.

From 1974 to 1976, Viola lived in Florence, serving as technical director for Art/Tapes/22, one of Europe’s first video art production studios. This period proved decisive: working closely with European artists, curators, and theorists, Viola refined both his technical mastery and his philosophical approach. His work became increasingly introspective and existential, concerned less with narrative than with states of being, durations, transformations, the space between appearance and disappearance.

One of his earliest installations, Migration (1976), already contained the seeds of what would become his signature language: slowness, repetition, elemental imagery, and the use of technology as a mirror of the soul. By the time he returned to the United States, Viola had already developed a singular vision, one that merged the spiritual intensity of medieval mysticism with the quiet power of video.

In these early works, the radical lies not in shock or provocation, but in silence, duration, and presence. Viola was not interested in spectacle; he was building a new kind of image, one that asked to be contemplated, not consumed.

The Poetics of Time and Transformation

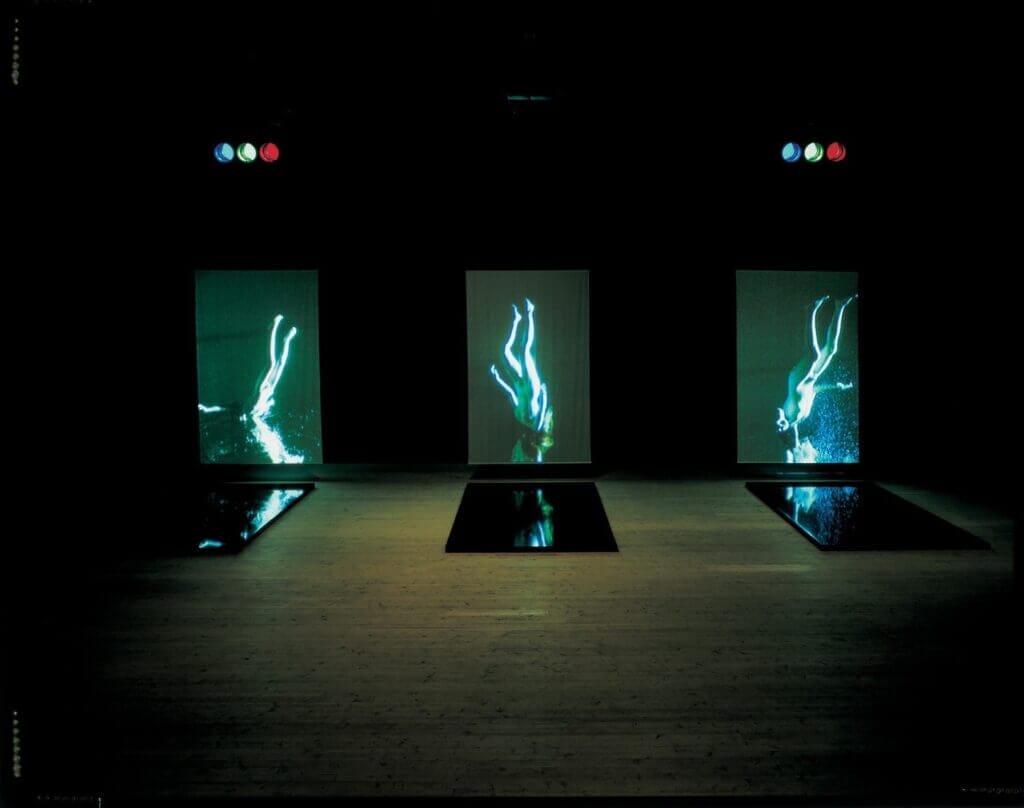

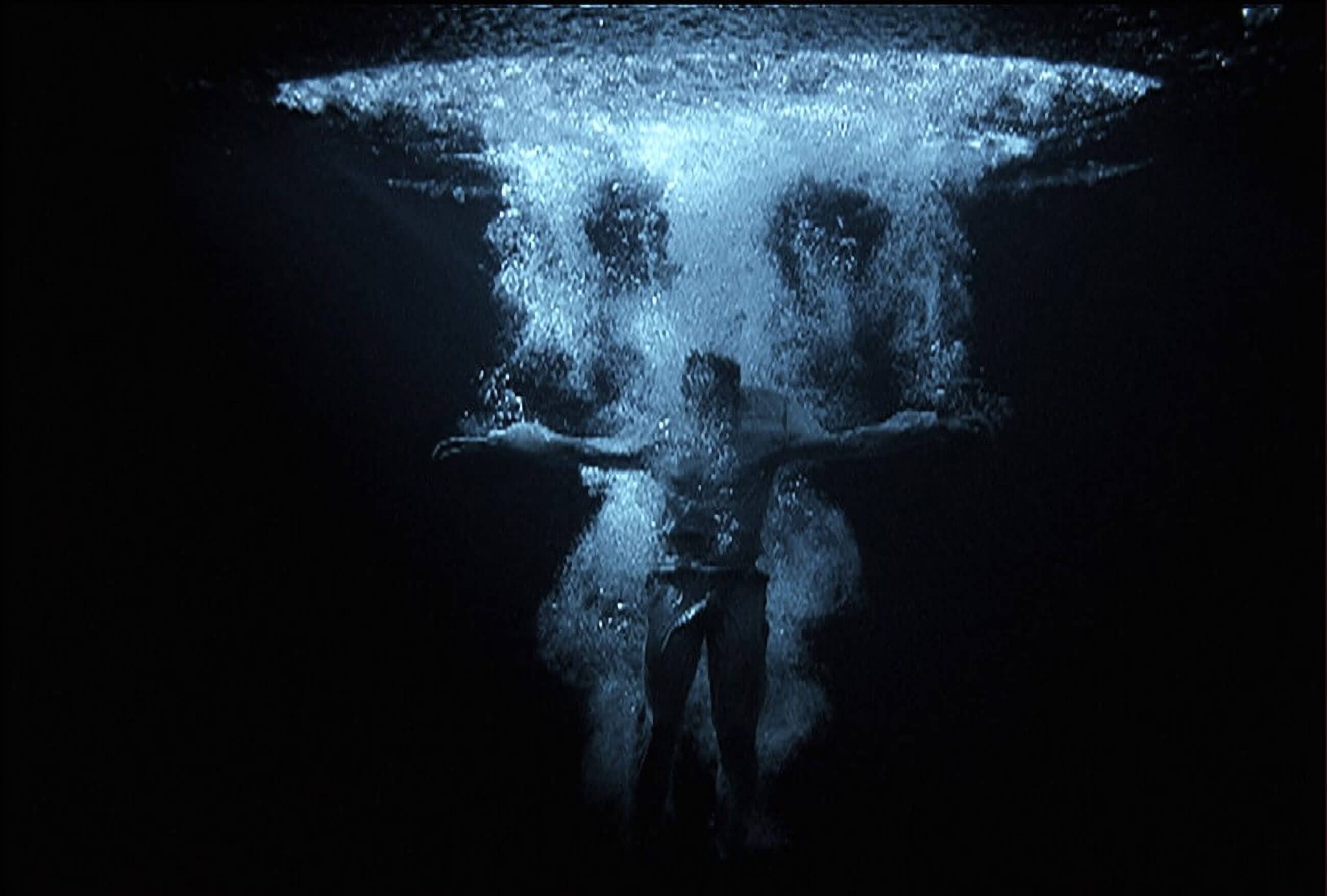

At the heart of Bill Viola’s work lies a deep and enduring preoccupation with time, not as chronology, but as experience. From his earliest installations to his most iconic large-scale projections, Viola has consistently treated time as a sculptural force, something to be stretched, dilated, slowed to a point where the invisible becomes perceptible. His videos rarely depict action in the conventional sense; instead, they stage transformation, suspension, and the passage between worlds.

This poetics of duration is never merely aesthetic. It is grounded in a metaphysical inquiry that spans across religious, philosophical, and cultural traditions. Viola’s exposure to Zen Buddhism, Christian mysticism, Islamic Sufism, and the writings of the Desert Fathers shaped his vision of the self as fluid, porous, and in constant flux. In his universe, the body is not a fixed identity but a vessel in motion, a site where suffering, ecstasy, death, and rebirth unfold in cyclical rhythms.

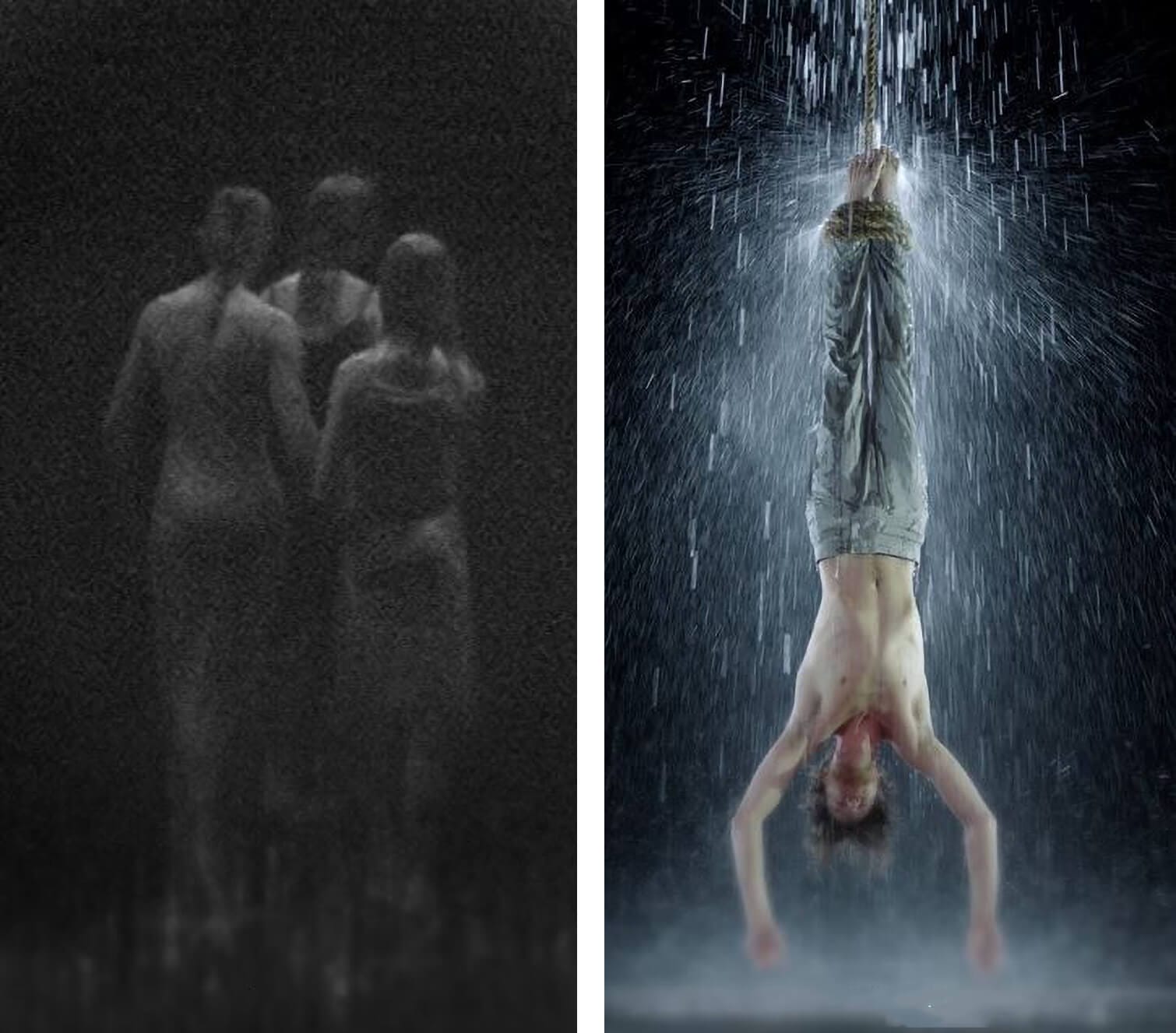

His characters, often suspended in water, engulfed in flames, or emerging from darkness, are not actors in the traditional sense. They are emblems of states of being, mirrors of archetypal experience. Viola uses extreme slow motion not to dramatize, but to reveal. What passes in an instant in daily life, grief, joy, breath, release, is drawn out to its fullest perceptual threshold, inviting the viewer into an intimate and contemplative relationship with the image.

Water, in particular, becomes a recurring metaphor: for memory, for baptism, for the unconscious. Viola’s figures submerge and reemerge, dissolve and reconstitute, mirroring the very processes of transformation that define human life. Just as light passes through water, so too do emotions pass through us, distorted, refracted, often only visible once we’ve allowed them the time to surface.

The spiritual is always close at hand in Viola’s work, but never didactic. His images speak the language of ritual, but without doctrine. They call upon the viewer not to believe, but to feel, to stand still in front of the screen and encounter the sacred in slowness, in vulnerability, in the intimate texture of human presence.

In this way, Bill Viola has redefined video not simply as a medium, but as a space for inner experience. His works are not watched; they are entered. They demand presence, patience, and a willingness to linger at the threshold between seeing and understanding.

Collaborations and Iconic Exhibitions

Behind every major artist stands a quiet architecture of relationships, and in Bill Viola’s case, no figure is more essential than Kira Perov. More than a lifelong partner, Perov has been his closest collaborator, editor, producer, and the organizing force behind much of his practice. Their partnership, both personal and professional, has endured for over four decades, shaping the very texture of Viola’s work. Together, they have constructed an oeuvre that is at once technically precise and spiritually expansive, balancing Viola’s visionary instincts with Perov’s editorial clarity and organizational rigor.

Throughout his career, Viola has cultivated a practice that resists the isolating myth of the solitary artist. His works often involve teams of camera operators, lighting designers, and sound engineers, but always in service of a singular vision, one that fuses intimate emotion with formal control. The studio, for Viola, becomes a kind of sacred space: part laboratory, part monastery, where technology is wielded with reverence rather than spectacle.

The resonance of his work has led to some of the most important exhibitions in the history of video art. Major retrospectives have been held at institutions such as the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Getty Center in Los Angeles, the Guggenheim in Bilbao, and the Grand Palais in Paris. In each of these contexts, Viola’s installations, often immersive, multi-channel, and cathedral-like in scale, have transformed the museum into a space of quiet revelation.

Yet perhaps most striking has been his ability to bring contemporary video into ancient and sacred spaces. Works like Martyrs (2014) and Mary (2016), commissioned for permanent installation at St. Paul’s Cathedral in London, represent a profound shift in the cultural perception of video art. Here, moving images are not distractions from the sacred, but expressions of it—modern extensions of devotional iconography. In these works, flickering screens occupy the same reverent space once held by stained glass or altar paintings, affirming the continuity between spiritual art of the past and contemporary media.

This dialogue between old and new, between the sacred and the digital, is part of what makes Viola’s exhibitions so singular. Whether staged in the minimal white cube of a museum or the shadowed nave of a cathedral, his installations never impose, they invite. They ask the viewer to stop, to breathe, to feel. In a world saturated with speed and spectacle, Bill Viola offers the rarest of experiences: a space for stillness.

Bill Viola and the Dialogue with Art History

Bill Viola’s work has often been described as contemporary, but it is deeply rooted in the past. His videos are in constant conversation with the long lineage of Western painting, particularly with the religious, symbolic, and emotional intensity of Renaissance and Baroque art. In this sense, Viola is not a rupture in art history, but a continuation of it. His screens do not reject the canon; they reanimate it.

One of the most striking aspects of his practice is the way he absorbs the visual language of old masters, not through imitation, but through translation. In Viola’s world, the chiaroscuro of Caravaggio becomes a moving shadow; the suspended gestures of Giotto or Masaccio find new resonance in his slowed-down figures; the mournful grace of a lamentation scene is distilled into a single body trembling underwater or consumed by flames.

Take, for instance, The Greeting (1995), a work directly inspired by Pontormo’s Visitation. Viola transforms the fleeting encounter of two women into a prolonged, almost timeless exchange, filmed in ultra-slow motion. What lasts only seconds in the original painting becomes a meditation on human connection, spiritual recognition, and the transmission of unspoken emotion. The composition, the colors, the folds of fabric, all echo the original, but the temporal shift changes everything: it becomes an image you feel as much as see.

This relationship to historical art is not nostalgic. Rather, it is conceptual. Viola believes in the continuity of human experience, birth, death, grief, transcendence, and sees classical art not as distant, but as alive with those eternal themes. By slowing down time, by isolating gesture, he brings us closer to the psychic core of these ancient images. His work is a kind of archeological excavation, not of material, but of emotion.

In this sense, Viola occupies a unique place in contemporary art: he uses the most advanced digital tools to recover something primal. His images speak to the present, yet feel outside of time. They bypass irony and commentary in favor of direct, almost liturgical presence. The screen becomes a threshold, like the canvas once was, through which the viewer confronts not just the image, but themselves.

What emerges from this dialogue with the past is not mere homage, but a reinvention. Viola reclaims video, often associated with fragmentation and distraction, and transforms it into a sacred site. His work stands as proof that even in the age of pixels and algorithms, it is still possible to create images that carry weight, silence, and soul.

Legacy and Relevance: A Spiritual Gaze in the Digital Age

In an age defined by velocity, distraction, and saturation, Bill Viola’s work stands as an anomaly, an act of resistance. His images unfold not with urgency, but with reverence. They ask nothing more of the viewer than presence. And perhaps that is why they remain so vital today: in a culture obsessed with immediacy, Viola’s work reclaims time, offering slowness as a form of knowledge, and stillness as an act of rebellion.

What makes Viola’s legacy unique is not simply his technical mastery or his early role in legitimizing video art within institutional contexts. It is his insistence that technology can still serve the soul. In a landscape where digital tools are often associated with noise, spectacle, and commodification, Viola reminds us that the screen can also be a sanctuary. His works are not content, they are experiences. They don’t shout; they listen.

Today, many of the themes Viola has spent decades exploring, mortality, transformation, the body as a vessel of spirit, feel more relevant than ever. In an era of artificial intelligence, virtual identities, and algorithmic lives, his practice offers a counterpoint: a space to feel, to grieve, to wait. His installations, often towering in scale yet intimate in tone, invite viewers to confront what is most essential, breath, emotion, fragility, the cyclical nature of existence.

Younger generations of artists, especially those working with time-based media, owe much to Viola’s pioneering vision. But his influence is not merely formal. It is ethical. He has shown that the digital need not be disembodied; that contemporary art can be both conceptually rigorous and emotionally devastating; that images can still carry mystery, weight, and transcendence.

In the ever-shifting topography of contemporary art, where trends come and go with algorithmic speed, Bill Viola’s work remains anchored, calm, unshaken, and luminously human. It reminds us that beneath the noise, there is silence. Beneath the spectacle, there is depth. And beneath the surface of the image, there is always the possibility of revelation.

fakewhale

Founded in 2021, Fakewhale advocates the digital art market's evolution. Viewing NFT technology as a container for art, and leveraging the expansive scope of digital culture, Fakewhale strives to shape a new ecosystem in which art and technology become the starting point, rather than the final destination.

You may also like

From Detroit to New York to Brussels: Five Artists Redefining the Concept of Sculpture

In recent years, the concept of sculpture has undergone significant transformations, influenced by a

Beatrice Vorster, Szilvia Bolla, Sabrina Ratté, Evangelia Dimitrakopoulou, Amélie Mckee, and Melle Nieling, “LOG 3: Interceptor,” at Plicnik Space Initiative, London.

“LOG 3: Interceptor” by Beatrice Vorster, Szilvia Bolla, Sabrina Ratté, Evangelia Dimit

Uncertain Index by P1xelfool: Objkt’s First Native Generative Art Release

On Wednesday, July 10th, Objkt.com will debut “uncertain index” by p1xelfool, marking th