Blurring Boundaries: Yiming on Machines, Organisms, and the Future of Hybrid Art

Yiming’s work consistently navigates the blurred boundaries between the organic and the synthetic, the conscious and the constructed, the human and the machine. Her hybrid sculptures and low-tech installations dwell in a liminal space, one that questions not only the role of technology in shaping perception, but also the desires and instincts behind our drive to transcend the body. At FakeWhale, we had the pleasure of speaking with Yiming about her evolving relationship with machines, organisms, and the mythologies we build around them.

Fakewhale: Your work often interrogates the tension between reality and simulation, life and mechanism. In Deceptive Behavior, you examine the illusion of consciousness and how we project sentience onto mechanical systems. How do you think our perception of “intelligence” is shifting today, especially in an era when machines seem to exhibit agency and autonomy?

Yiming Yang: Deceptive Behavior explores the tendency to interpret patterns of behavior as indicators of sentience or strategy. Intentionality is often projected onto systems that exhibit motion or structure, even in the absence of awareness. This reveals a broader perceptual ambiguity: the line between what is genuinely alive and what merely imitates life is becoming increasingly difficult to define. In this context, intelligence is not treated as a fixed attribute, but as a relational phenomenon that emerges through the interaction between body, object, and environment.

The concept of “deception”, both in the natural world and in human-made technologies, appears frequently in your practice. What draws you to this idea, and how do you see the parallels between evolutionary mimicry in animals and the increasingly lifelike behaviors of machines?

Deception is a survival mechanism. In nature, mimicry allows certain species to escape predators or attract mates. There is something both profoundly strategic and beautifully primitive about it. I find it compelling when this logic appears in human systems, especially when we design forms that imitate life or emotion to provoke a response. Whether it is a flower mimicking a bee or a structure triggering empathy through motion, deception becomes a tool for coexistence and transformation.

Donna Haraway famously wrote, “Our machines are disturbingly lively, and we ourselves frighteningly inert.” This resonates strongly in your kinetic sculptures, which appear animated yet remain confined to mechanical patterns. How do you interpret this paradox in your work?

That paradox is central to what I explore. My sculptures move, pulse, and respond, but they are trapped in mechanical cycles, unable to break free. At the same time, humans often passively observe them, projecting emotion while remaining still. The irony is that we become more inert while these forms appear increasingly animated. Though the sculptures are not alive, they confront us with our own expectations of liveliness, purpose, and autonomy.

In Cyborg, Archetypes, and the Ever-present Bodies, you express resistance to overly symbolic or fixed readings of your sculptures. How do you approach the viewer’s interpretation, and what strategies do you use to keep the works open-ended or resistant to categorization?

The materials I use, such as discarded mechanical parts, carry traces of their past functions, but no longer belong to a fixed identity. By reconfiguring them into unfamiliar forms, I disrupt their original narratives and create space for more ambiguous and instinctive encounters. I am not interested in viewers decoding a specific message or symbolic meaning. I prefer for them to respond viscerally. Many of my pieces emerge from an intuitive or instinctive process. They invite interpretation without demanding it.

Your relationship with discarded industrial materials feels tactile, almost instinctive. When starting a new piece, do you begin with the form of the material itself, or do you start from a more conceptual or imagined image?

It’s a mix. Sometimes a concept leads me to seek out specific materials, and other times, the material itself initiates the direction of the work. My process rarely begins in a linear way. It feels more like a dialogue between form and thought. Eventually, there is a point where the work begins to reveal itself, and that is when I know how to move forward.

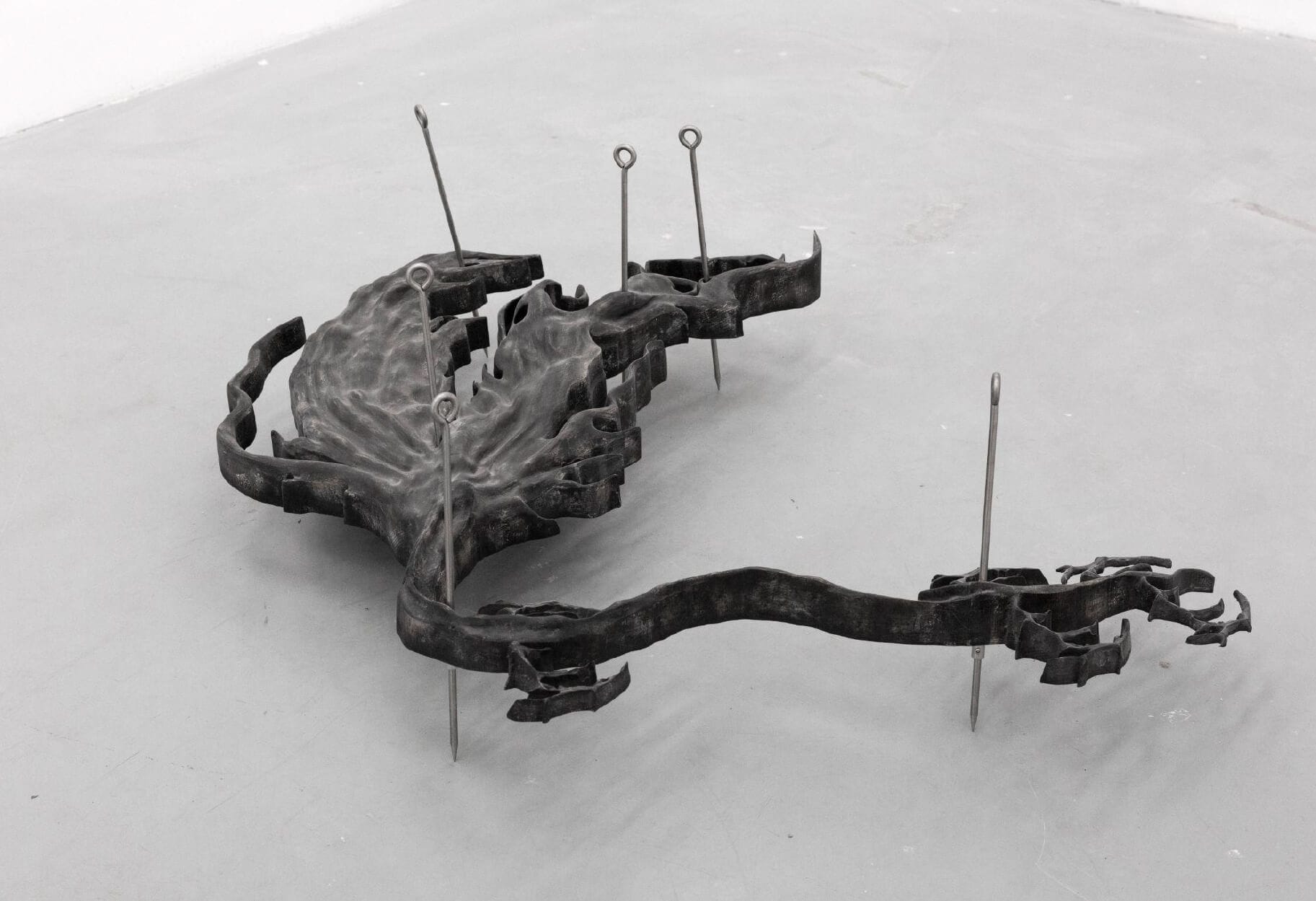

In Spore Dispersal Machine (2025), you reference fungal behaviors to explore hidden patterns of communication and adaptation. How does the language of plants and fungi help you rethink subjectivity or agency outside of a human-centered framework?

Fungi and plants operate in ways we rarely perceive. They network, adapt, and communicate without central control or visibility. This decentralization challenges conventional ideas about agency. In Spore dispersal machine, I wanted to highlight a form of intelligence that is subtle, distributed, and collective, not based on dominance or self-awareness but on entanglement and mutual responsiveness. It is a reminder that agency can exist in stillness, in spores, and in quiet transformations.

Recently, your work seems to be turning toward the idea of enchantment as a form of resistance to rationalism—particularly in Enchantment (Re-enchantment), where myths and fairytales re-emerge. What does it mean for you to “re-enchant” the present moment, and why do you think this is important now?

To re-enchant is to reclaim ambiguity, mystery, and wonder. I see it as a form of resistance to the modern impulse to explain, categorize, and reduce everything to function or data. Myths and fairytales carry emotional truths that rational thinking alone cannot access. In Enchantment (Re-enchantment), I wanted to create spaces where suppressed or forgotten forms of knowing could resurface. It is not about escaping reality, but about deepening our engagement with it through metaphor, emotion, and the unknown.

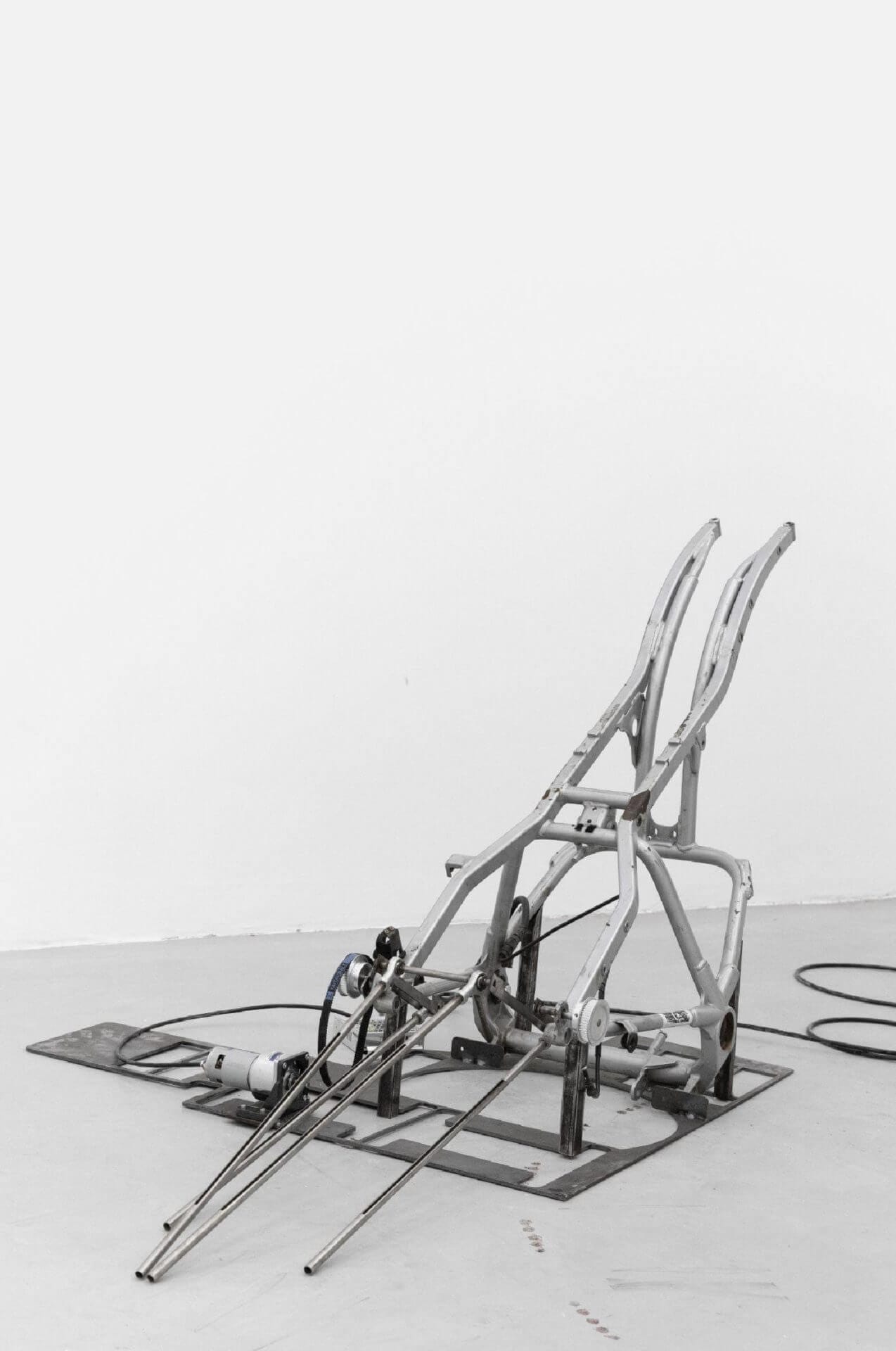

In works like Parts, behaviour, deployment and Motion pattern, your cyborgs appear trapped in repetitive, almost purposeless gestures. What relationship are you exploring between repetition, control, and desire in these kinetic routines?

Repetition can signify both comfort and confinement. These figures are caught in loops that resemble longing, like an insect endlessly scratching the floor or a body attempting to move forward but remaining in place. Their gestures simulate escape without ever achieving it. To me, repetition mirrors human behavior, the way we return to routines driven by habit, desire, or compulsion. There is a quiet sadness in that repetition, but also a strange kind of endurance.

Looking back at Barbie Nonsense Instrument (2019), a work with a more playful, satirical tone, we still see a strong thread around the body, identity, and machine logic. How has your approach to these themes evolved since that early piece?

That piece was more direct. It deconstructed a cultural icon, exposed its circuitry, and made it absurd. Over time, my approach has become quieter and more internal. I’m still exploring body and identity, but now through ambiguity and tension rather than satire. I am interested in what happens when a body is unresolved, when it is neither fully human nor fully machine. Identity in my recent work is felt more than declared. It has become a slower, more intimate inquiry.

- What directions are you currently exploring in your practice? Can you share any thoughts about future projects or emerging concepts that are still in development?

Lately, I have been drawn to the fragile boundaries between species and space, particularly how insects, often seen as wretched or alien, intervene in human environments.

This idea emerged during my recent residency at MacDowell, where I lived in a house surrounded by forest. In that environment, daily encounters with insects entering the studio space became a quiet but persistent reminder of how porous our boundaries really are.

In upcoming works, I plan to explore these tensions through building materials that blur the line between infestation and cohabitation. I am interested in how small, irritating organisms expose deeper vulnerabilities within human-centered systems. Their movements, which appear erratic and unpredictable, stand in contrast to the rigid logic of domestic and technological environments. Their presence challenges our assumptions of control and purity.

Rather than using insects as symbols, I want to embody the intensity of their presence and their ability to provoke discomfort, anxiety, and fear. These works reflect on ecological ethics, spatial boundaries, and the unease that arises when what we try to keep out inevitably enters. They are not intended to provide answers, but to create space for reflection.

What directions are you currently exploring in your practice? Can you share any thoughts about future projects or emerging concepts that are still in development?

Lately, I have been drawn to the fragile boundaries between species and space, particularly how insects, often seen as wretched or alien, intervene in human environments.

This idea emerged during my recent residency at MacDowell, where I lived in a house surrounded by forest. In that environment, daily encounters with insects entering the studio space became a quiet but persistent reminder of how porous our boundaries really are.

In upcoming works, I plan to explore these tensions through building materials that blur the line between infestation and cohabitation. I am interested in how small, irritating organisms expose deeper vulnerabilities within human-centered systems. Their movements, which appear erratic and unpredictable, stand in contrast to the rigid logic of domestic and technological environments. Their presence challenges our assumptions of control and purity.

Rather than using insects as symbols, I want to embody the intensity of their presence and their ability to provoke discomfort, anxiety, and fear. These works reflect on ecological ethics, spatial boundaries, and the unease that arises when what we try to keep out inevitably enters. They are not intended to provide answers, but to create space for reflection.

fakewhale

Founded in 2021, Fakewhale advocates the digital art market's evolution. Viewing NFT technology as a container for art, and leveraging the expansive scope of digital culture, Fakewhale strives to shape a new ecosystem in which art and technology become the starting point, rather than the final destination.

You may also like

Between Prom Nights and Protest Signs: Anne Imhof’s DOOM House of Hope at the Park Avenue Armory

We at Fakewhale followed the buzz around Anne Imhof’s much-anticipated return to New York, where h

Luis Maria Sulzmann, Untitled, at Ping Pong, Copenhagen

“Untitled” by Luis Maria Sulzmann, at Ping Pong, Copenhagen, 02/10/2025–10/10/2025. Wh

Fakewhale Presents FAKEWHALE STUDIO

We are pleased to present FAKEWHALE STUDIO, a research platform committed to the scholarly explorati