Pauline Cordier, Holding Time at Andata Ritorno – Laboratoire d’Art Contemporain, Geneva

Holding Time by Pauline Cordier, at Andata Ritorno – Laboratoire d’Art Contemporain, Geneva, 12/09/2024 – 05/10/2024.

The term “white cube” is often used to describe the exhibition space reduced to its minimal conditions. However, the ideal of purity and neutrality implied by this term is a veil that can be lifted with minimal attention, revealing the material, social, institutional, and ideological realities that shape it. Pauline Cordier’s exhibition, Holding Time, at the Andata Ritorno gallery, provides a peculiar perspective on the exhibition space itself, which seems to invite us to engage in a reflection where the art space mirrors itself. However, she extends our perspective beyond the self-referential aesthetic object that defines this place. The artist creates a decentering shift, focusing on how the space is itself exhibited, in the transitive sense of what is exposed to something in this case, exposed by the passage of daylight to the space outside. This «outside» encompasses the street, the sky, and even the astronomical coordinates that make it all go round. Through a window, functioning as a light gauge, the artist spent a year measuring the rectangle of light projected into the gallery at noon. The geometry of the Earth’s orbit around the sun shapes parallelepipeds whose dimensions vary according to the angle formed by the Earth’s position relative to the sun.

With the Earth’s axis tilted at about 23 degrees, the northern hemisphere, where the gallery is located, is exposed variably to the sun. During the summer solstice, the northern hemisphere is «turned» toward the sun, allowing light to enter through the window at noon at an angle of about 67 degrees, creating a small rectangle. Conversely, in winter, the Earth exhibits the gallery at a sharper angle, around 20° during the winter solstice on December 21. With the sun lower in the sky, it projects the largest, yet least intense, surface of light. Ultimately, no space can reflect only itself unless it is closed off to the forces of the world, which include not only social and institutional movements but also non-human ones. In this sense, every artwork is like a Foucault pendulum, the famous device experimented in a cellar in 1851 to prove the Earth’s rotation: each artwork in some way indexes movements that extend beyond the art space. The aesthetic challenge, then, is to decide which movements to capture from the multitude that influence the work. In Your Sun Machine (Marc Foxx Gallery, Los Angeles, 1997), artist Olafur Eliasson pierced the roof of the space, allowing a disc of sunlight to enter and move across the space as the day progressed. This minimalist and radical form gave shape to the movement of the Earth.

As for Pauline Cordier, she invites us to experience more composite dynamics. From these seemingly ordinary yet dizzying phenomena that mark the gallery’s orbit around the sun, she recorded rectangular indices, transcribed into twelve aluminum plaques covered with reflective canvases, which are redistributed throughout the space. Passersby and vehicles outside cast shadows and reflections onto these canvas-like windows, creating multiple temporal layers of light—combining the instantaneous reflections of street movements with the seasonal rhythms of the Earth’s orbit. The photosensitive dimension of the exhibition space, which seems to function like a photographic chamber, or more precisely a photoplastic one, also reveals itself in a phenomenon of great depth.

The gallery floor, coated with paint containing photochromic pigments, darkens when exposed to UV light, subtly shifting in shades of grey tinged with violet depending on the exposure intensity. Unlike film used in traditional photography, where light leaves dark traces in a negative image, here the light gradually colors the exposed surface, and the process is reversible. Thus, strange visual paradoxes emerge with the rhythm of the light’s movements in the space, slowed by the delayed reaction of the pigments and inverted by the relative brightness left on the floor by shadows. What seems to be the shadow of a window frame, for instance, suddenly detaches as a lighter form when a body passes in front of the light beam, casting its own shadow onto the trace. The dark silhouette drawn in negative by the light reveals the clarity of a previous shadow, reinforcing the contrast of the photochromic pigment’s reaction on the floor: the dark area deepens, while the relative brightness of the obscured zone surfaces. And the longer we observe this phenomenon, the whiter the mark left by our shadow becomes. In Pauline Cordier’s work, the ancient Greek concept of skiagraphia, or shadow drawing referring to the appearance of things, plunges into a new spatio-temporal depth. The immediate shadow reveals the shadow of the past, as though shadows exist in layers of time, creating a surprising relationship where darkness is inversely proportional to duration: the longer the shadow lasts, the brighter its outline becomes.

Yet, due to the heliocentric movement, this relationship remains precarious, as nothing is fixed photographically—no writing, no drawing is recorded, and no moment is captured. Holding Time, therefore, does not mean stopping its flow but following the inexorable rhythm of space at the speed of shadows. Here, shadows possess a speed that seems to diverge from their binary relationship to light. No longer simply defined as «the absence of light», shadows unfold with their own spatiality and temporality. As the light moves the shadow cast by an object, the trace of what could be called the object’s prior «skialogic» state lingers in the space for a while; the new, darker shadow drawing what looks like the shadow of a shadow. While the exposure to sunlight’s movements produces a kind of cosmological decentering, the simultaneous exposure to the variations of shadow situates us in the necessarily local experience of a layered duration.

In composing these movements, Pauline Cordier presents the exhibition space functioning as a grey cube.

David Zerbib

fakewhale

Founded in 2021, Fakewhale advocates the digital art market's evolution. Viewing NFT technology as a container for art, and leveraging the expansive scope of digital culture, Fakewhale strives to shape a new ecosystem in which art and technology become the starting point, rather than the final destination.

You may also like

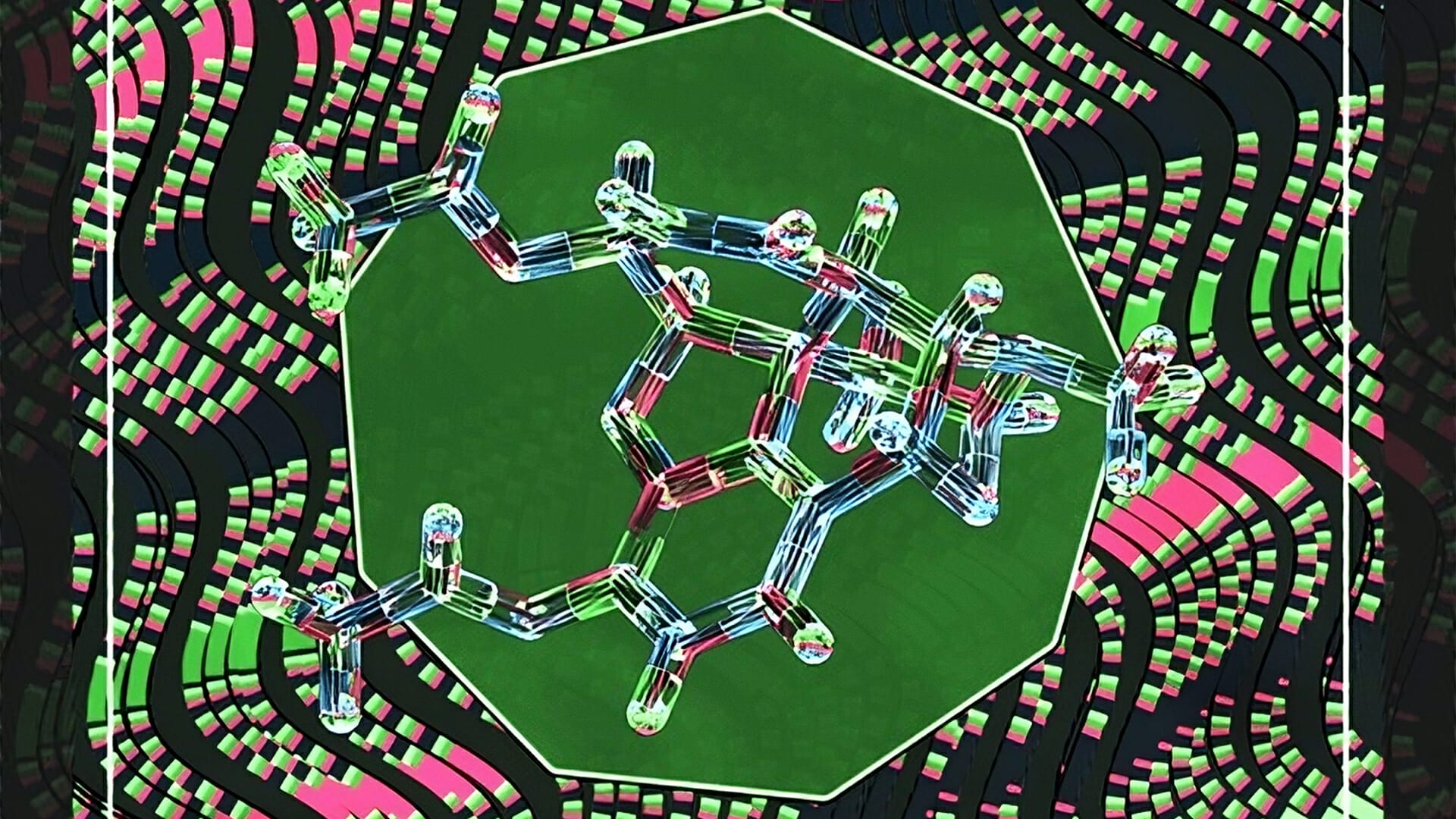

xSublimatio is a “merging” aesthetic digital drug experience

The project is the first to be incubated by Faction.art TO MINT ON : https://faction.art/project/x

Sarah Neumann, Tom König, Suzie Callisz, Maria Margolina, Jakob Floess, and Maxim Tur, “Cryptogramme,” at Komplot, Brussels.

“Cryptogramme” by Sarah Neumann, Tom König, Suzie Callisz, Maria Margolina, Jakob Floes

Fakewhale Physical I: The Fakewhale Vault Permanent Collection

At its foundation, the Fakewhale Vault is an innovative curatorial project that aligns the tradition