Niklas Roy in conversation with Fakewhale

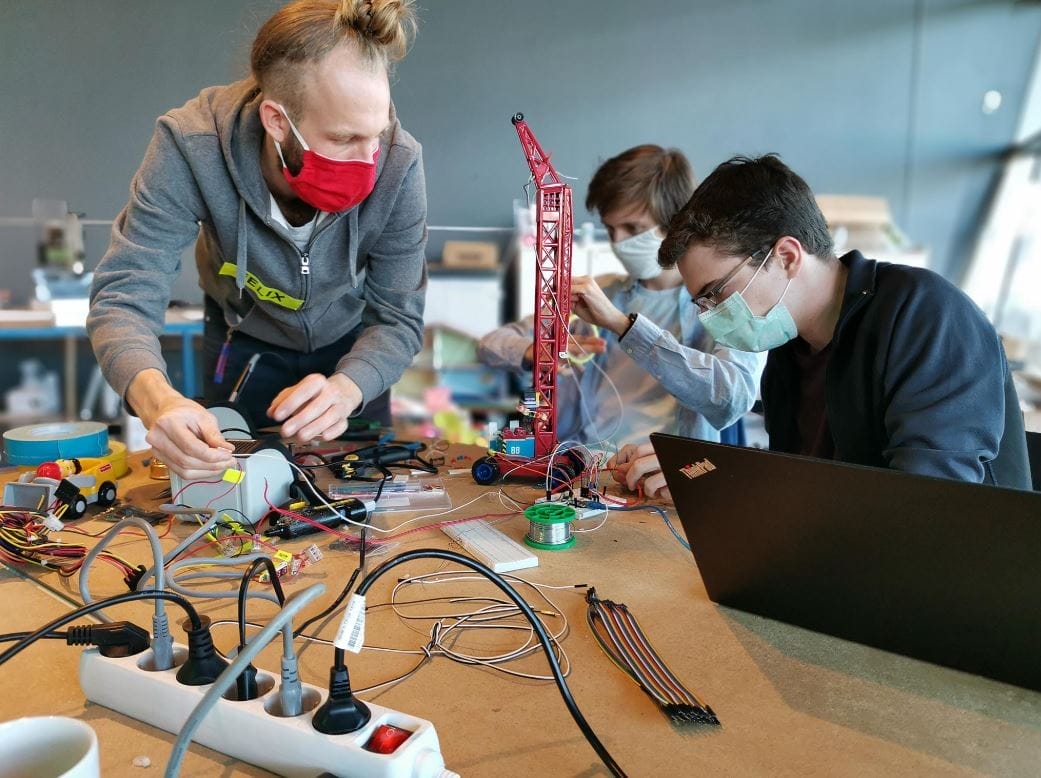

Niklas Roy’s work turns technology into playful, interactive experiences that blend art, engineering, and science. With a background in 3D animation and visual effects, he reinterprets obsolete inventions, repurposes everyday objects, and invites audiences to engage with technology in unexpected ways. His installations, often infused with humor and irony, challenge our perception of automation, creativity, and the digital world.

Fascinated by his ability to merge technical ingenuity with artistic expression, Fakewhale reached out to Roy for a conversation about his creative process, his approach to open-source sharing, and how he balances past and future in his work.

Fakewhale: You started your career in the film industry as a 3D animator and visual effects supervisor. How has that background influenced your approach to interactive art and invention?

Niklas Roy: I’ve always been fascinated by the magic of film, how visual effects create worlds that don’t physically exist. But film remains an illusion. With my machines and interactive installations, I found a way to bring that magic into the real world, turning imagination into something tangible and interactive. My background in film still influences how I think about appearance, timing, and how an artwork gradually reveals itself to an audience.

2. What made you transition from film to building machines and interactive installations? Was it a moment of rupture or a natural evolution?

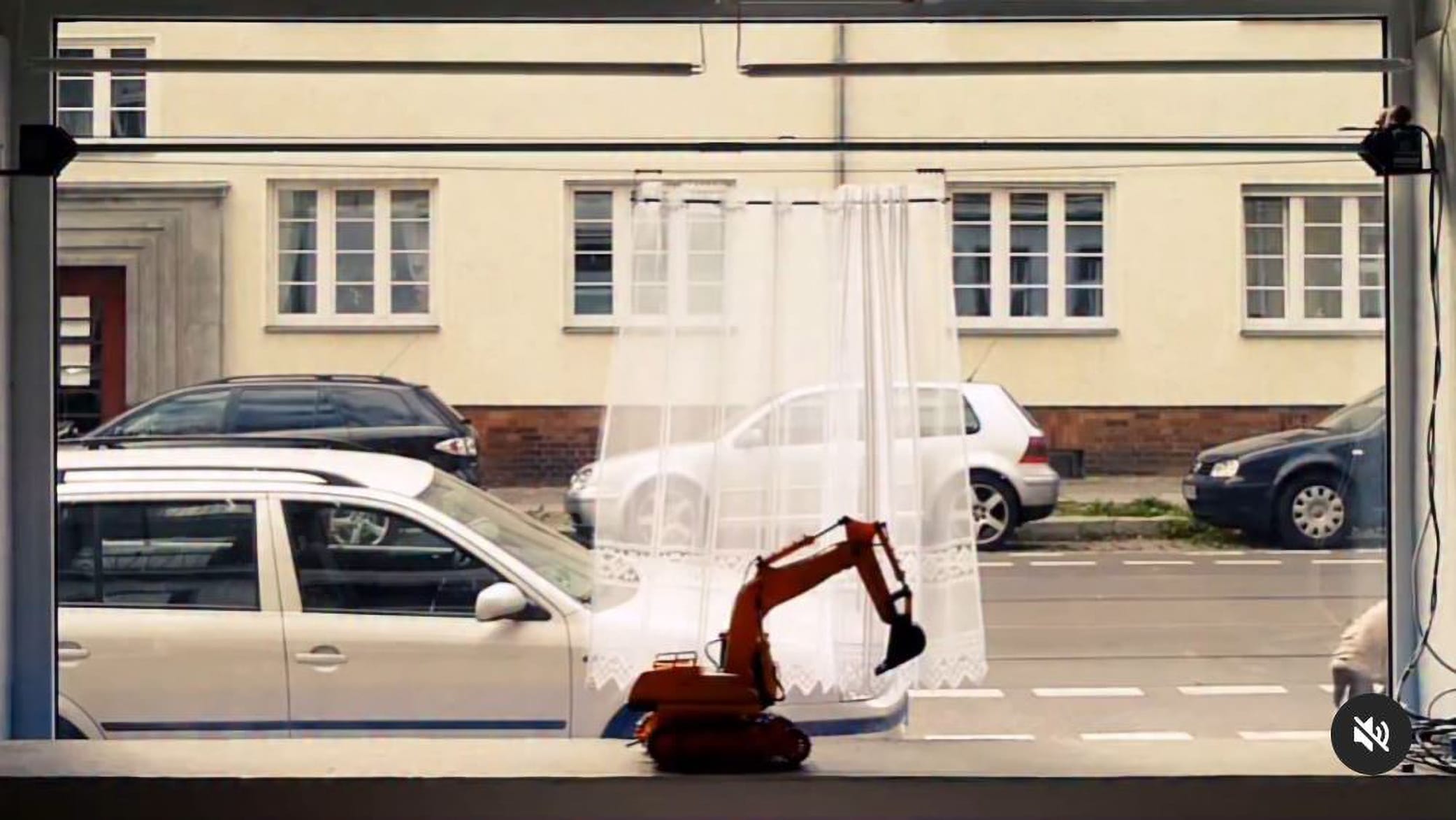

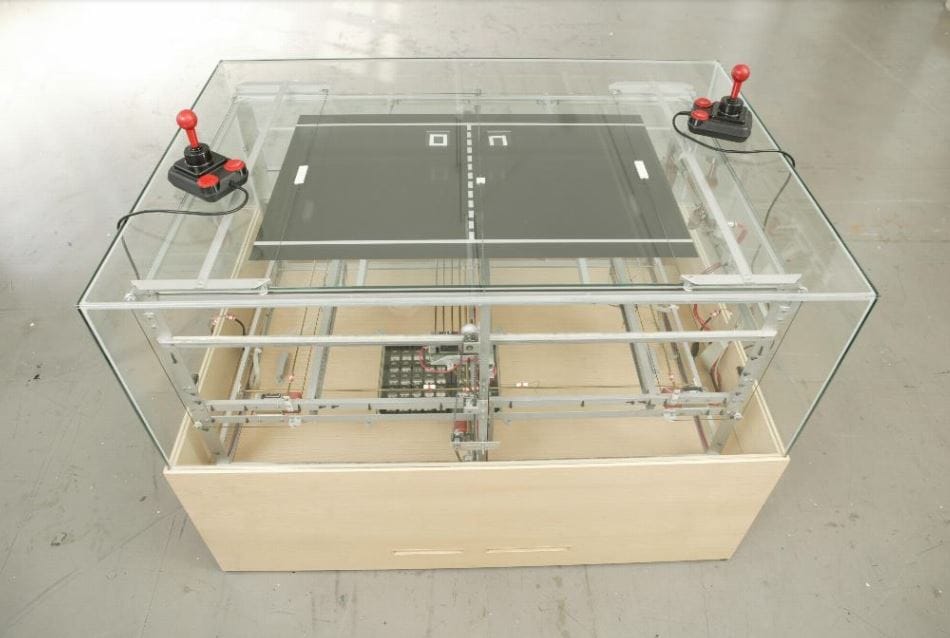

I got tired of the rigid hierarchies in the film industry, where every role is narrowly defined and stepping outside of it is discouraged. I wanted to be hands-on with every part of the creative process, so I moved toward making physical art instead. My early interactive works were also a direct continuation of my film background. Projects like “Pongmechanik” or “Grafikdemo” took digital experiences and translated them into physical, mechanical systems. It was my way of reinterpreting digital interactions and making technology feel more immediate and tangible.

3. Your work sits at the crossroads of art, technology, and science. Which of these fields do you feel most connected to, and which challenges you the most?

Technology appeals to me because it follows logical principles. Science, as its foundation, offers a similar clarity. Art, on the other hand, is ambiguous—there’s no right or wrong, and it can’t be measured. That’s both liberating and frustrating. I’m drawn to art that has a strong conceptual or technical aspect—works that invite intellectual or physical engagement rather than just passive viewing.

4. Many of your projects have a playful and ironic quality while still being deeply technical. How important is humor in your creative process?

Humor is essential—not just in my work, but in life in general. It keeps me sane and adds an element of surprise, even in highly technical or conceptual pieces. I’d say that my works themselves aren’t necessarily funny, but humor happens in the mind of the audience, when something clicks, when expectations are subverted, or when an absurdity is revealed. I enjoy creating work that operates on multiple levels, intellectually, technically, and playfully, so if it sparks both thought and a smile, I consider that a success. I think the art world generally needs more humor.

5. You’ve created installations for both science museums and public spaces. How does your approach change when designing for these different environments?

The biggest difference is the audience. In a science museum, visitors have chosen to be there—they’re naturally curious and willing to engage with an installation. In public spaces, people encounter the work unexpectedly, often in the middle of their daily routines. Because of this, the piece needs to be visually inviting, and the interaction must be immediate and intuitive. If it’s not instantly appealing or clear how to engage, people are likely to move on.

For example, “Visitors Magnet,” an installation I created for Technorama, a science center in Switzerland, was designed for an audience inclined toward discovery. Meanwhile, the “Mosaikmaschine” an installation that toured a neighborhood in Berlin, was designed to create spontaneous interactions and participation which led to a permanent public artwork , the “Maschinenmosaik”. The way a piece has to function in its environment shapes how I design it—both conceptually and technically.

6. Your work often reveals the unexpected, playful side of technology. Do you think technology is taken too seriously today?

Not really. I think most people don’t take technology seriously enough, they just consume it. There’s an eagerness to own the latest gadget or use the newest service without questioning its implications on their lives and society in general.

Personally, I’m less interested in the latest devices and more fascinated by fundamental scientific and technical principles. History has so much to offer in this regard. There have been countless brilliant inventions that are now obsolete, but if you revisit them with today’s knowledge and recreate their core principles with current tools, they can suddenly feel fresh and relevant again.

7. Open-source sharing is a key part of your philosophy. How do you see this mindset shaping the future of art and innovation?

Sharing knowledge benefits everyone. Copyright and secrecy primarily serve as tools for corporations to maintain a competitive edge in a capitalist world, where intellectual property is treated as an asset. But creativity thrives on openness—on remixing, reinterpreting, and building upon existing ideas rather than locking them away. The software world, with its strong open-source culture, is a great example, and I think the art world could learn a lot from it.

8. Technology evolves rapidly, yet many of your creations have a timeless appeal. How do you ensure that your work remains relevant over time?

I avoid the latest trends. What looks futuristic today often feels outdated tomorrow. Instead, I like to use recycled technical components, placing them in unexpected contexts. Individually, these parts might seem old, but together, they create something fresh. It’s that contrast between familiarity and novelty that, hopefully, keeps my works, if not forever relevant, at least unique.

9. AI is increasingly present in creative fields. Do you think it will fundamentally change the role of artists like you who work with technology? Or do you see it as just another tool in the artist’s toolbox?

AI is a powerful tool, and it looks like it’s going to change everyone’s role—not just artists. Like any technology, it opens new possibilities while reshaping how most of us work. The challenge is using it thoughtfully rather than letting it dictate the process.

10. You’re constantly experimenting with new ideas and materials. Is there a technology or concept you haven’t explored yet but find particularly exciting?

Acoustics and sound really fascinate me. I love how something as mathematical as harmonies and rhythm can create such immediate emotional responses. I’ve built several generative synthesizers in the past, but I still have plenty of concepts in mind that I want to bring to life.

11. What’s next for you? Are there any upcoming projects you’re especially excited about?

I have an exhibition opening next week in Ghent, Belgium, where I’ll debut my new installation, “Generative Art 1€”. It’s a vending machine for generative art, it continuously produces an endless stream of unique line drawings, displaying them as an animation on a modified flat screen. Drop in a one-euro coin, and you get a plotted version of the drawing on paper. The audience becomes the curator, deciding which drawings deserve to be materialized, while also assigning them a value.

Another project I’m excited about is “Schulgong,” a public art installation for a new school building in Nuremberg. It reinvents the traditional school bell, replacing it with a modified glockenspiel, actuated by solenoids, that plays a different melody each time it rings. Students will even be able to compose and contribute their own pieces. I like the idea of turning a repetitive signal into a space for creativity, where routine becomes a moment of surprise and self-expression. This will be my next major endeavor, and I’m eager to see how it will turn out.

fakewhale

Founded in 2021, Fakewhale advocates the digital art market's evolution. Viewing NFT technology as a container for art, and leveraging the expansive scope of digital culture, Fakewhale strives to shape a new ecosystem in which art and technology become the starting point, rather than the final destination.

You may also like

Fakewhale presents SYNTHETIC PROGRAM on SuperRare

Launching exclusively on premier digital art platform SuperRare on November 27th, 2024, Fakewhale pr

7 – An Unlikely Friendship

Somewhere in Montana, United States Dasher approached the scent of incense through the thick forest.

Simona Andrioletti, Text me when you get home <3 at DG Kunstraum, Munich

“Text me when you get home <3” by Simona Andrioletti, curated by Benita Meißner, at