Thinking in Images: André Malraux and the Museum Without Walls

The Curatorial Gesture as Artwork

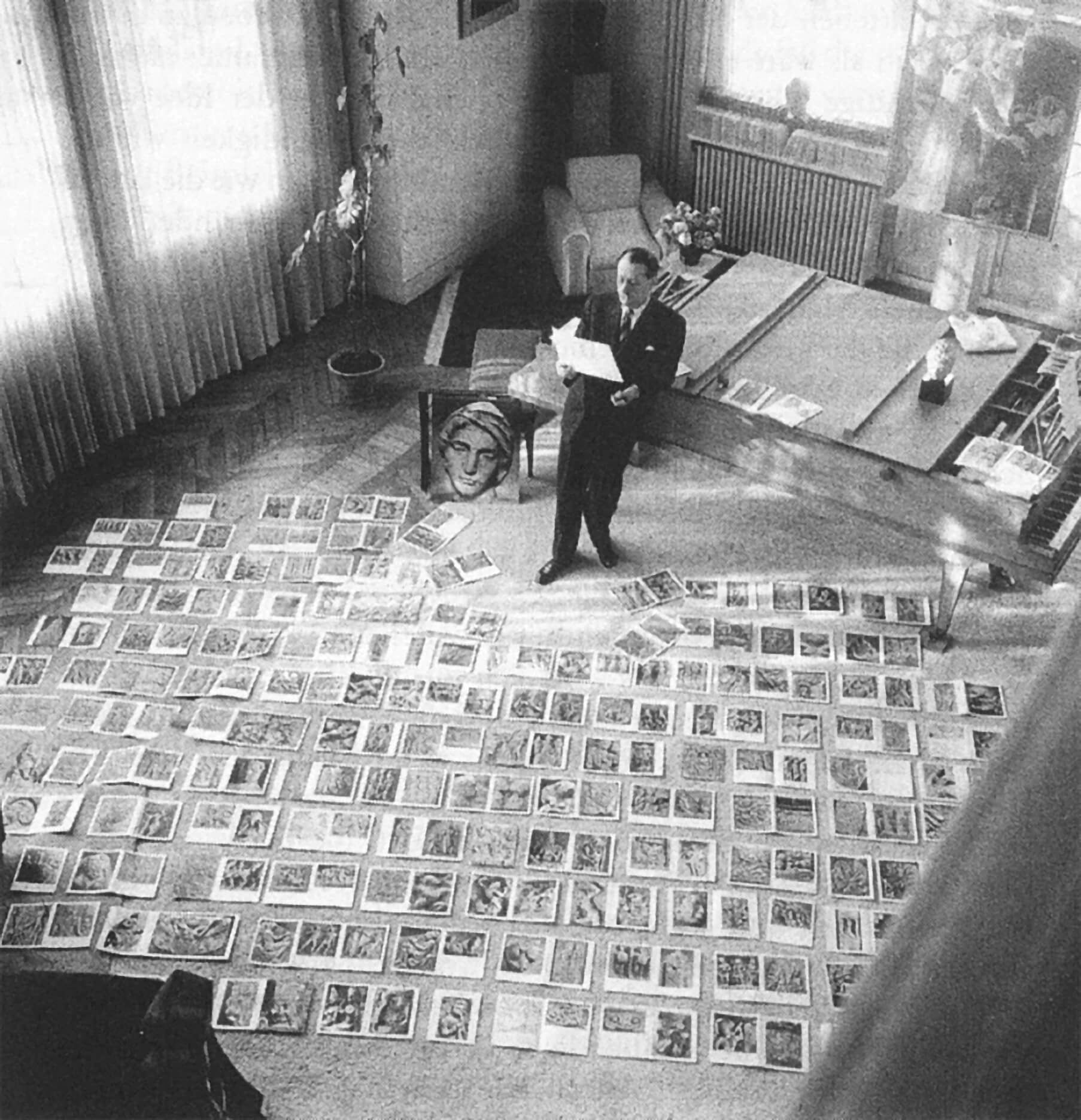

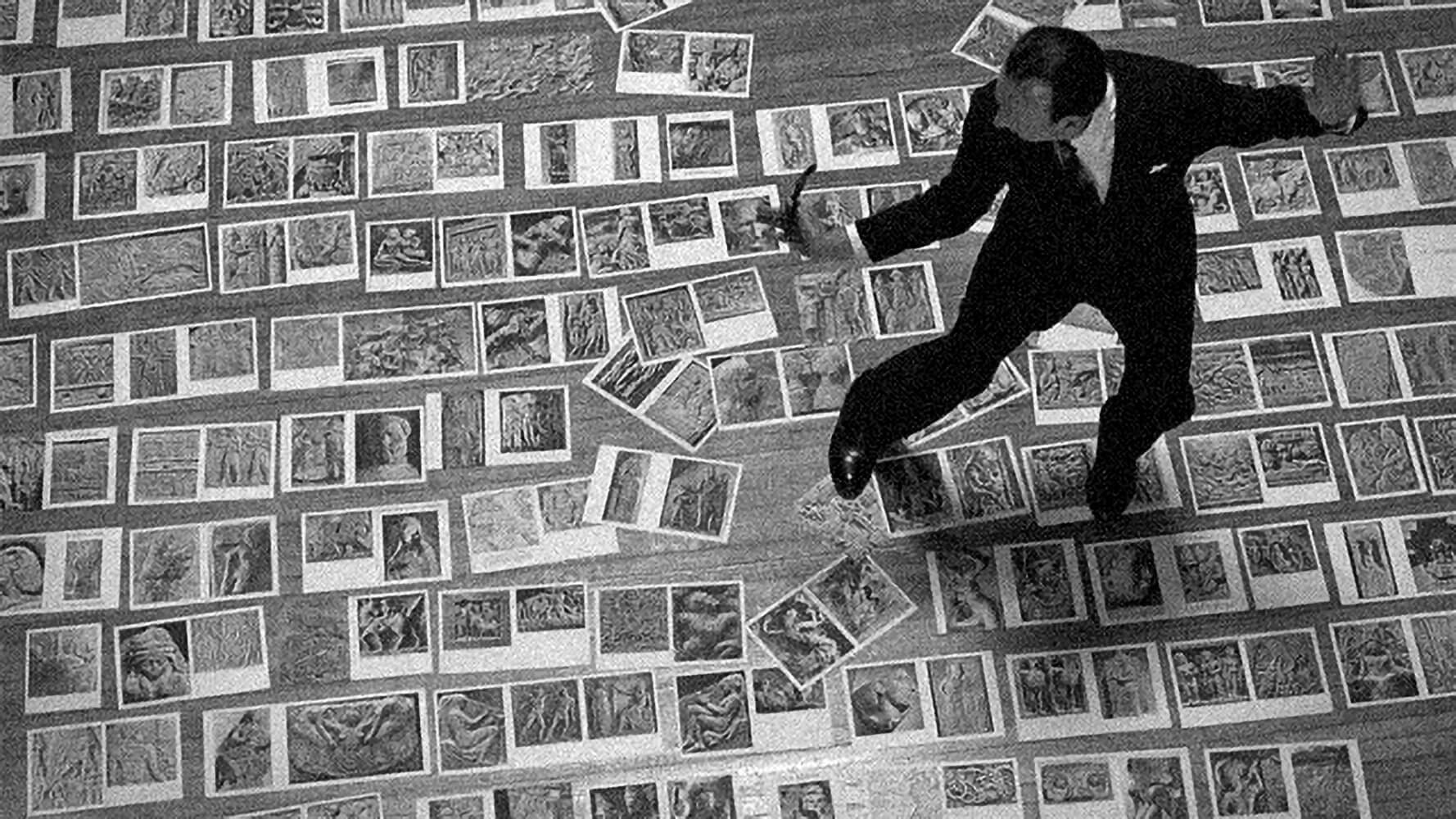

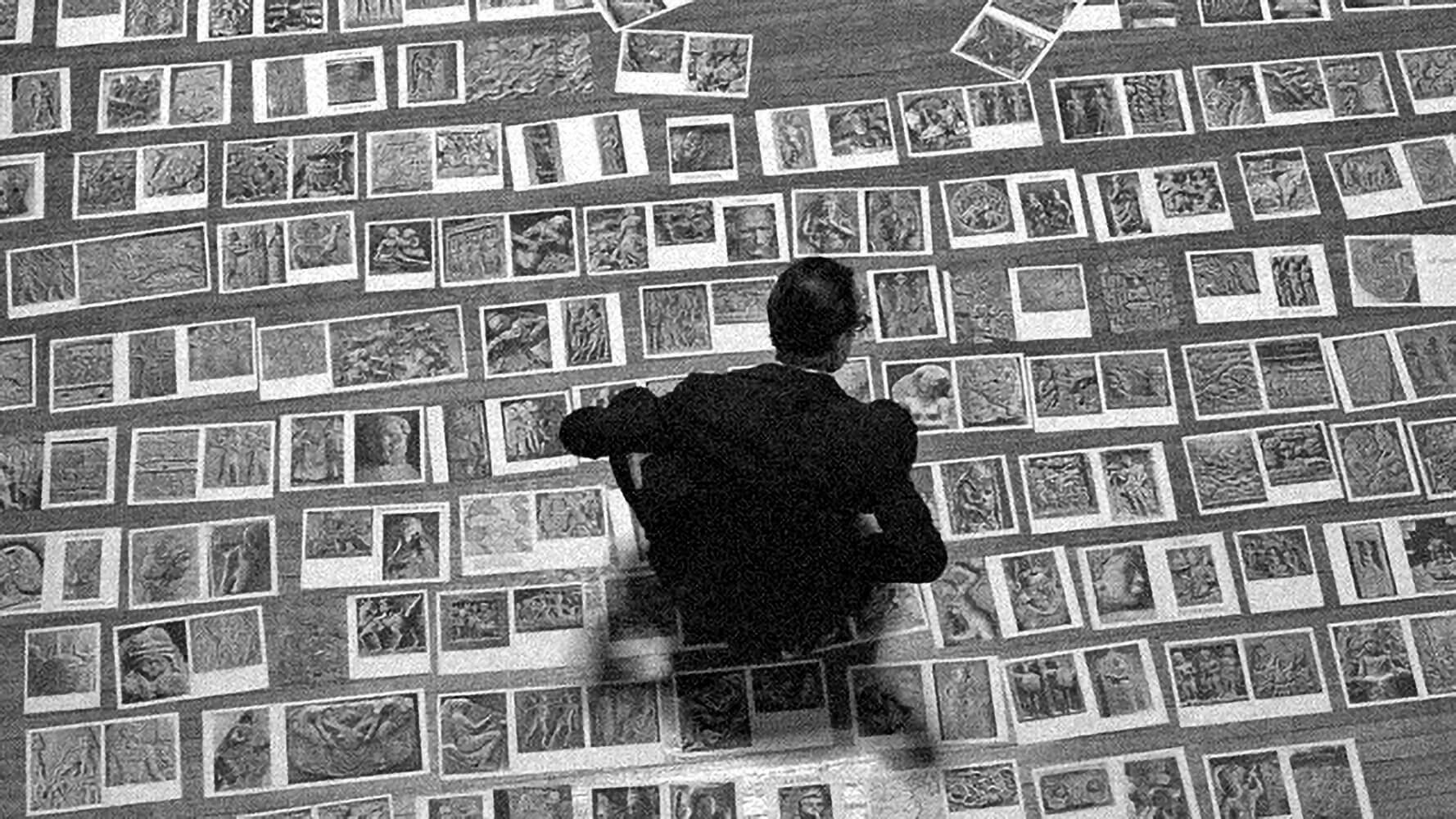

The photograph of André Malraux, surrounded by a constellation of images laid across the floor, does not depict a moment of preparation or research, it enacts a gesture of creation. What we witness is not an editorial pause but an authorial act. Malraux’s posture, absorbed and upright, does not suggest passive observation but a form of embodied editing, a choreography of attention that elevates the arrangement of images to the status of expressive form. In this sense, the curatorial gesture ceases to be secondary to the work of art and becomes itself a work, a visual syntax through which meaning is not just transmitted, but actively produced.

This elevation of curating to the level of authorship emerges not through the institutional figure of the curator, but through a solitary and philosophical practice of montage. Malraux does not assemble an exhibition, he composes a visual argument. Each image on the floor is a fragment in a larger discursive architecture, a unit in a visual language through which historical time is collapsed and reordered. The act of juxtaposition operates as a syntax of affinities and tensions, turning the floor into a space of thought. The horizontal layout rejects any hierarchy between the images, it does not monumentalize, it activates.

To understand this gesture as artwork is to recognize its critical refusal of the traditional museum apparatus. There are no walls, no categories, no chronological progression. What Malraux constructs is a heterodox image-field, a mobile surface where sculpture from Khmer temples can appear next to a Renaissance figure, where a mask from the Congo can mirror the contours of a Greek kouros. This simultaneity resists historical containment. It proposes a way of seeing based on resonance rather than lineage, echo rather than origin.

Malraux’s gesture anticipates a condition that has become central in contemporary visual culture, the turn from object to image, from the aura of the artwork to the logic of its circulation and recombination. By laying these fragments bare and vulnerable on the floor, he signals a rupture: art is no longer where it is supposed to be, and the act of placing becomes as significant as the thing placed. The studio becomes a site of exhibition, the private act becomes a public proposition, and the curatorial gesture, stripped of institutional framing, acquires the intensity of authorship.

In this reconfiguration, what is displayed is not only art, but the act of thinking through art. Malraux’s studio-floor becomes a cognitive map, a performative diagram where the curatorial and the conceptual merge. It is no longer a place where works are gathered, but a site where meaning is generated through their encounter. This is not simply a new way of looking at art, it is art as a way of thinking.

The Museum Without Walls: Theoretical Device and Mental Space

When Malraux coined the notion of a “musée imaginaire”, he was not simply proposing a poetic metaphor. He was designing a theoretical tool, a cognitive architecture meant to displace the traditional museum as the exclusive site of artistic validation. The museum without walls, as he would later call it, radically untethered the artwork from the institutional, spatial, and cultural regimes that had long governed its visibility. What emerges is not a dream of accessibility, but a critical operation: to relocate the power of the museum into the field of the image.

This dislocation is not innocent. By replacing the aura of the physical object with the circulating photograph, Malraux foregrounds a crisis in the ontology of the artwork, one that resonates powerfully with the concerns of Walter Benjamin. And yet, while Benjamin mourns the loss of the aura, Malraux mobilizes its dissolution as a new potentiality. In the museum without walls, the image becomes an agent, not of reproduction, but of translation, relation, and construction.

What Malraux enacts is the shift from a museum of containment to a museum of flows. The spatial boundaries of the institution dissolve into a mental field, an imaginary assemblage in which artworks from disparate traditions can coexist, interact, and transform one another. The museum is no longer a building, it becomes a surface of reflection, a site of encounter between vision and knowledge. This transformation anticipates not only the archive-based practices of contemporary art, but also the algorithmic logic of today’s image environments, where curation becomes infrastructure and display becomes code.

Malraux’s museum is neither universal nor neutral. It is explicitly constructed through the act of selection, reproduction, and recombination. It reveals the constructedness of any canon, the editorial nature of visibility itself. By presenting sculptures, masks, and figures as photographs, stripped of scale and context, he levels them into visual thought-objects, each equally available to be recontextualized. In doing so, he undermines the rhetoric of authenticity and opens the possibility for heterogeneous epistemologies of art.

This is not to say that Malraux’s museum escapes its own limitations. His selections, like any curatorial act, are conditioned by taste, access, and cultural bias. But what matters here is not the inclusiveness of the museum, it is its structural shift. The musée imaginaire does not ask to replace one canon with another. It asks whether the very form of the museum can become a thinking machine, a space where art is not preserved but activated, not stabilized but re-imagined.

In this sense, the museum without walls is not a site of accumulation, but a theoretical device. It reveals that what we call a museum is never simply a collection of objects, it is a proposition about what images can mean, how they can be shown, and where knowledge begins. And in that moment, as Malraux stands over his sea of photographs, we do not see a man lost in contemplation, we see the museum thinking itself into a new form.

Reproduction and the Authority of the Image

In Malraux’s imaginary museum, the photographic reproduction is not a surrogate of the artwork, it is its transfiguration. The image does not merely reference the original, it enacts a displacement, a shift from the ontological weight of the object to the epistemic potential of its image. This displacement is not incidental, it is the condition of possibility for Malraux’s entire operation. Without reproduction, the musée imaginaire would not exist. And yet, what he constructs is not a museum of copies, but a new regime of presence, a presence without materiality.

This shift signals a decisive moment in the history of art’s mediation. If in the traditional museum the authority of the artwork derives from its physical uniqueness, here it is the image that acquires sovereignty. The photograph, once an ancillary device for study, becomes the primary interface of access, comparison, and meaning. The image no longer points back to an origin, it functions autonomously, within a new grammar of visual relations. As such, it is not only a record, but a form of thought.

Malraux’s gesture anticipates what will later become a foundational tension in contemporary art discourse, the question of whether the image is a derivative or a producer of value. In his arrangement, the distinction collapses. The reproduction is no longer secondary, because the notion of originality itself is suspended. What matters is not where the image comes from, but what it does, how it operates within a conceptual field. This move opens up the possibility for artworks to be activated through documentation, rather than diminished by it.

This logic finds resonance in the post-war turn toward dematerialized practices, where photography begins to document, expand, or even replace the work of art. From conceptual art’s indexical strategies to performance’s photographic traces, from artists’ books to institutional critique, the reproduction becomes not a supplement to the work, but the site where the work occurs. Malraux’s arrangement, made of printed fragments laid across a floor, is an early and profound example of this dynamic. It constructs a space where meaning is not stored in the object, but distributed across images.

What emerges is a new economy of visual authority, one that no longer depends on authenticity or provenance, but on relational articulation. Malraux treats each photograph as a node in a network, not as a fetish of the real. In doing so, he severs the image from its subservience to the object, and installs it as the central agent of the curatorial gaze. This inversion, the reproduction as source rather than trace, undermines the hierarchy between original and copy, collapsing them into a shared field of operation.

The authority of the image in Malraux’s thought is therefore neither optical nor evidentiary. It is structural. It emerges from the image’s capacity to be placed, mobilized, recombined, to become part of a visual discourse that exceeds the logic of the individual artwork. In this sense, the photograph is not a representation, it is an apparatus, and the museum, finally, becomes a space of images without need for objects.

Horizontal Iconology

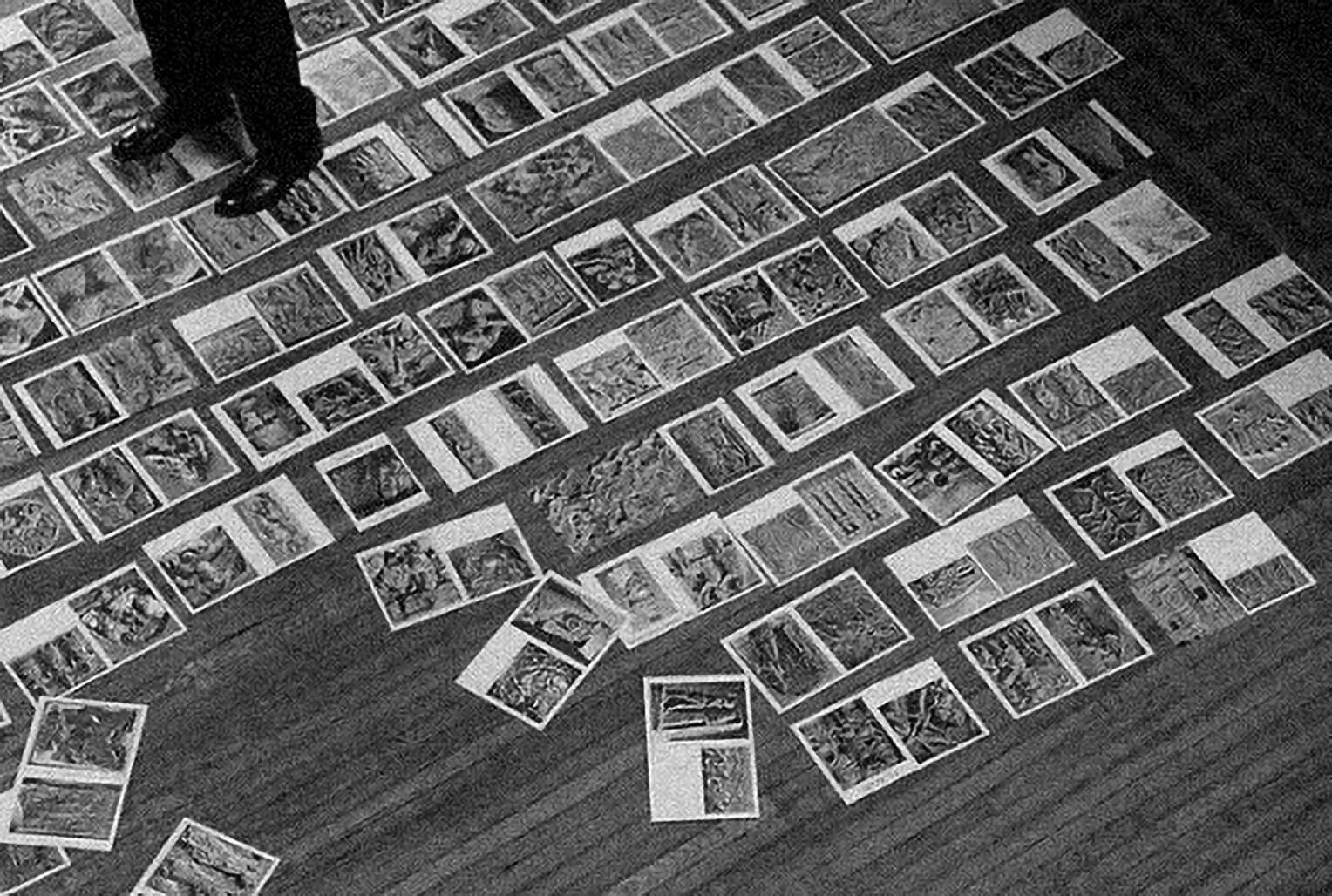

One of the most radical dimensions of Malraux’s musée imaginaire is not just what it contains, but how it is laid out. The physical arrangement of the photographs, spread across the floor in no apparent hierarchy, performs a visual statement that precedes and exceeds any theoretical claim. This horizontal field, devoid of pedestals, vitrines, or sacred distances, becomes a diagram of equivalence. Here, images are not subordinated to chronology, geography, or stylistic lineage, they coexist in a state of suspension, where proximity generates meaning more than provenance.

This is not merely a visual convenience. It is an epistemological rupture. By flattening the structure of display, Malraux contests the verticalities of art history, the pyramidal logic of periodization, influence, and evolution. Instead, he proposes an iconology without elevation, where a sculpture from Gandhāra might rest beside a Gothic tympanum, and an African mask might echo the expression of a Baroque martyr. These are not illustrations of a thesis, they are encounters that disturb fixed narratives and allow new ones to emerge.

Such a horizontal iconology draws attention to the visual affinities that escape the frame of traditional discourse. It allows form to speak across time, material to resonate beyond culture, surface to suggest contact rather than containment. This is not a universalist flattening, but a strategic anachronism, a method of short-circuiting the usual taxonomies in favor of a thinking that moves by analogy, rhythm, intuition. It is a way of seeing that values visual logic over historical discipline, and in doing so, invites a more speculative, more open engagement with the image.

Malraux’s horizontal layout shares deep affinities with Aby Warburg’s Mnemosyne Atlas, where the black panels functioned as stages for the migration of images, allowing for iconographic constellations that escaped linear time. Both projects reject the museum’s vertical institutionality in favor of a spatial intelligence that privileges juxtaposition, resonance, and drift. But where Warburg’s atlas remained a wall-based mapping, Malraux collapses even that distance, his images lie underfoot, physically accessible, visually democratic, almost vulnerable.

This gesture also anticipates contemporary practices of display that refuse enclosure and monumentalism. The horizontal spread has since become a curatorial language in its own right, from archival tables in exhibitions to floor-based installations, from formless research displays to publishing projects that migrate between page, screen, and wall. In each of these, we can trace the legacy of Malraux’s staging of non-hierarchical vision.

The horizontal, in Malraux’s imaginary museum, is not just a format, it is a politics of form. It resists the dominance of the vertical axis, so often aligned with power, mastery, and central perspective. It proposes instead a ground-level seeing, a mode of attention that is less about dominion and more about relation. It is this shift, from looking at to looking with, that transforms the image from illustration into event, from document into site of encounter.

Archiving and Montage: Visual Strategies of Memory

The museum that Malraux assembles on the floor is not a stable collection, it is a mutable archive. It does not preserve but activates, does not fix but recomposes. Each image is provisional, each arrangement reversible. What emerges is not a taxonomy but a montage, a structure of thought that thinks in images, across them, and between them. The floor becomes a field of memory, not a storage of the past, but a choreography of its possible readings.

Malraux’s logic is not archival in the traditional sense. He does not accumulate documents in the service of institutional memory. Rather, he stages a mobile archive, one that operates through reconfiguration rather than conservation. The photographs are tools of movement, not containment. Their very material fragility, their paper textures, their susceptibility to rearrangement, reflects a conceptual agility, a refusal of closure. The archive, here, is a thinking surface, where the act of positioning is already a form of interpretation.

In this, Malraux’s practice converges with a broader lineage of visual thinkers for whom the archive is not a repository but a productive apparatus. From Warburg’s Mnemosyne Atlas to Gerhard Richter’s Atlas, from Hanne Darboven’s numerical accumulations to Walid Raad’s fictional files, the archive becomes a zone of conceptual potential, where the tension between order and disorder becomes generative. Malraux’s floor, strewn with images in flux, is not a chaos, it is a visual grammar unfolding in real time.

The technique of montage is central to this logic. Not simply as an editing method, but as a way of thinking that privileges relation over essence, sequence over identity. Malraux’s floor is not neutral: it is an editorial field where the syntax of juxtaposition replaces the authority of context. The artwork, removed from its historical pedestal, becomes a node in a relational structure. Meaning arises not from what the image is, but from where it is placed, how it echoes, what it touches.

This montage-based archive destabilizes the very premise of the museum as a space of permanence. Instead, it proposes a performative temporality, where the memory of art is not something stored but something staged. The image becomes a medium not of fixation but of reiteration. It can be re-seen, re-used, re-positioned. In this sense, Malraux does not only archive art, he archives possibilities of art, each new arrangement a potential exhibition, a thought experiment, a conceptual drift.

What is remembered in this system is not the past, but the capacity to remember differently. Malraux’s practice does not rescue artworks from oblivion, it rescues them from stability. By releasing the image into movement, he discloses an archive that breathes, a space of images not for preservation but for reanimation. And in doing so, he reveals the most profound function of the visual archive, not to store memory, but to activate it anew each time we look.

Documentation as Work: The Photograph as Performative Gesture

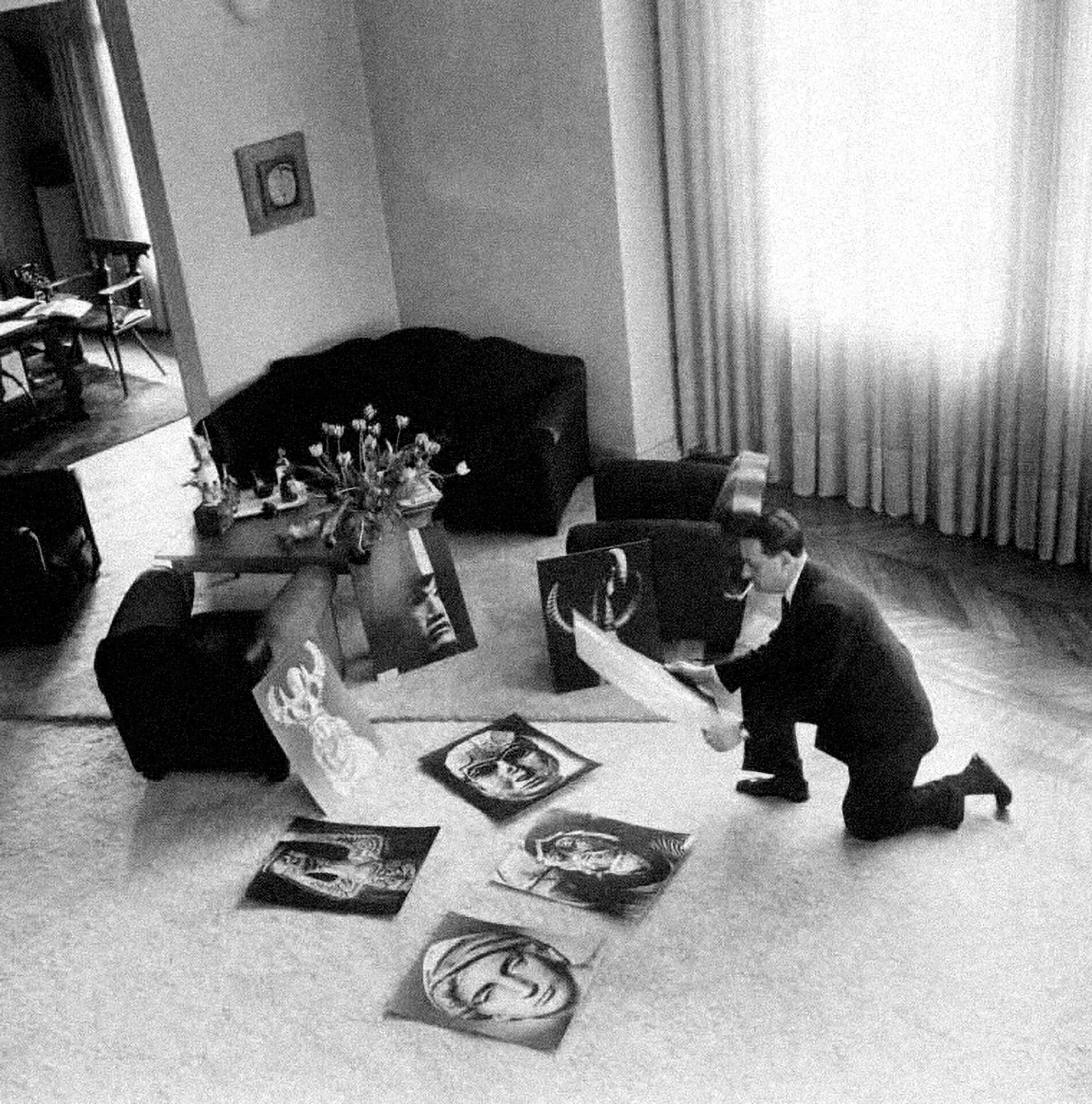

The photograph of André Malraux standing amidst a sea of images is often read as a document, an archival trace of a process, a backstage glimpse into a theorist’s studio. Yet to reduce it to documentation is to misread its operative nature. The image, captured by Maurice Jarnoux, is not simply a record of something that happened, it is the visual consolidation of a gesture that is, in itself, a form of making. In this sense, the photograph does not illustrate an idea, it performs it.

This performativity is not theatrical, but epistemic. The photograph stages the act of thinking with images, turning Malraux’s arrangement into a visible proposition. It does not point back to a hidden original, it is the original, insofar as it crystallizes a way of seeing, assembling, and signifying that cannot be otherwise captured. The documentation here does not follow the work, it constitutes it. The boundary between process and product collapses into an image that is both gesture and thesis, both private act and public statement.

This inversion anticipates a condition central to contemporary art: the increasing autonomy of documentation as a space of authorship. From conceptual art’s reliance on the photographic trace to post-internet practices that exist primarily as images in circulation, documentation is no longer a supplement, it is often the primary form. Malraux’s photograph prefigures this condition, standing at the threshold between the material history of the object and the immaterial future of the image.

The floor, covered with photographs, and the photograph of that floor: together they form a feedback loop, a system in which the image documents an operation that is itself about images. This recursive structure blurs the distinction between the archive and the act, between the artwork and its transmission. What is produced is not an object but a visual dispositif, a field of relations that is conceptual, spatial, and temporal all at once.

In this light, the image of Malraux does not belong to the genre of studio photography, nor is it a neutral report. It is a performative matrix, a photograph that theorizes as it shows, that does not frame a work but frames the very conditions of work. It invites us to consider documentation not as aftermath but as gesture, not as trace but as intelligence. The camera does not merely witness, it collaborates in the constitution of meaning.

Thus, Malraux’s legacy is not just the imaginary museum, it is the realization that in an age of images, the act of assembling, framing, and documenting is itself a site of creation. The image is no longer bound to the artwork; it becomes its continuation, its translation, sometimes even its replacement. What remains is not an object to be preserved, but a thought to be reactivated. And in that thought, we no longer observe the photograph, we inhabit it.

fakewhale

Founded in 2021, Fakewhale advocates the digital art market's evolution. Viewing NFT technology as a container for art, and leveraging the expansive scope of digital culture, Fakewhale strives to shape a new ecosystem in which art and technology become the starting point, rather than the final destination.

You may also like

Fakewhale in dialogue with Ofluxo

We have been following the journey of O Fluxo with great interest. As an online platform, it has d

Fakewhale in Conversation with Johannes Thiel

Introducing Johannes Thiel Born In 1999, Germany Visit Artist Website Johannes Thiel navigates throu

Lorenz Wanker, Trau dich grossartig zu sein at Galerie OK-KunZT, Klagenfurt

Trau dich grossartig zu sein by Lorenz Wanker, curated collaboratively by the artist and the venue o