Inside PXL DEX: How Kim Asendorf Tokenized the Building Blocks of Digital Imagery

In PXL DEX, one of this year’s most talked-about and successful digital art projects, Kim Asendorf reclaims the pixel, digital imagery’s most fundamental unit, by tokenizing each point of light on the Ethereum blockchain.

By merging abstract aesthetics with crypto infrastructure, Asendorf introduces a novel framework for digital ownership, redefining how we collect, display, and co-create art on the blockchain. In a market where engagement has become increasingly selective, PXL DEX has reignited interest among collectors, offering a dynamic model that challenges static ownership and scarcity. In this article, we explore the mechanics behind PXL DEX and speak with Kim Asendorf about the project’s conceptual and technical foundations.

A Glimpse at the PXL Ecosystem

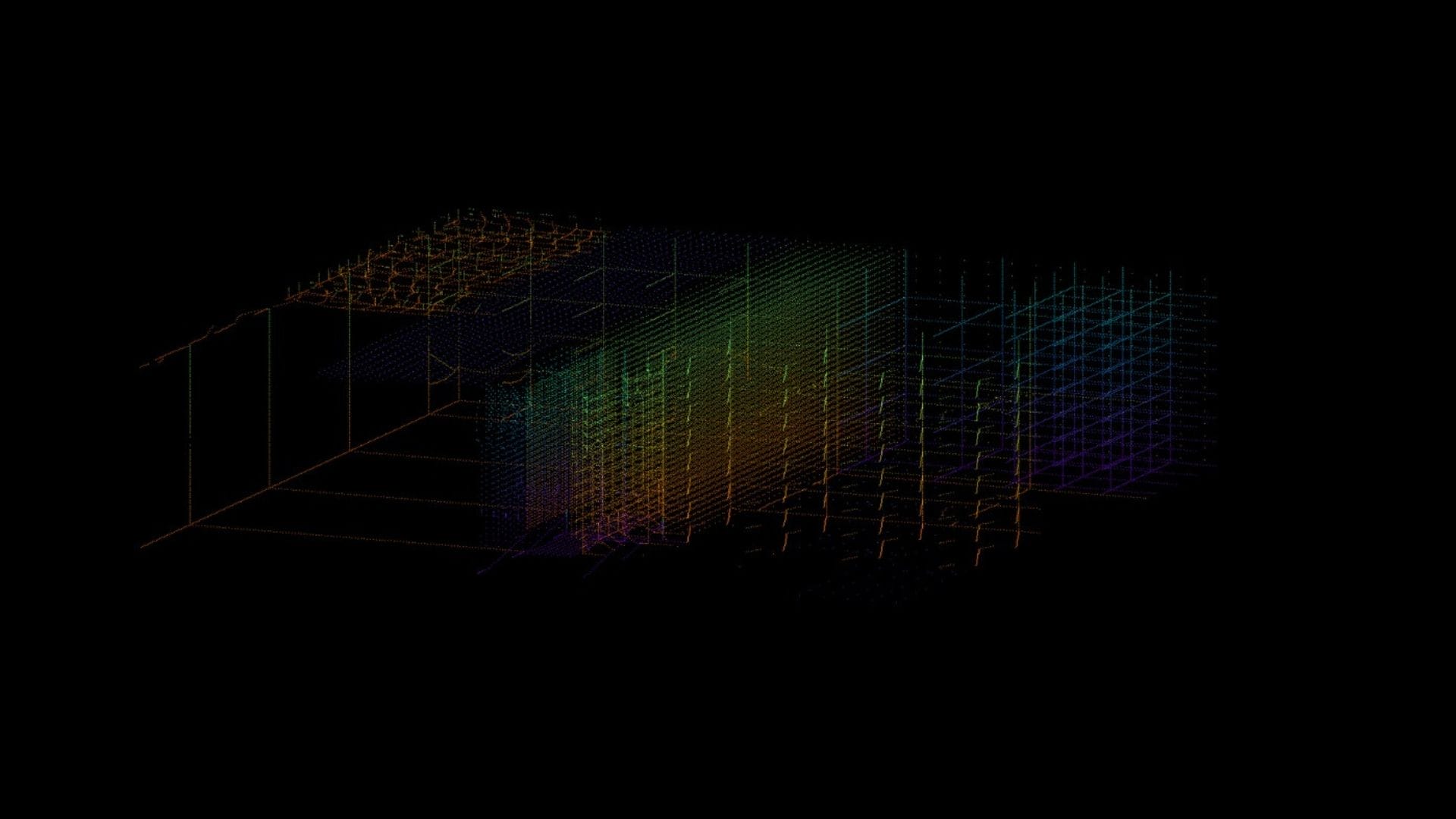

Each work in the PXL DEX series, known as a Deck, functions as a 3D animation that never loops. Deployed under a custom smart contract, every NFT draws upon Asendorf’s carefully written GLSL (WebGL2) and JavaScript code, without relying on the bulk of third-party libraries. Each Deck exists as a dense lattice (or a sparse constellation, depending on user choice) of flickering pixels on a black backdrop.

These pixels are not mere visual placeholders; they are PXL, an ERC-20 token that collectors can add to (or remove from) their NFT. A newly minted Deck can include up to 500,000 PXL tokens, with another 500,000 available to mint later. This malleability highlights a central theme of Asendorf’s practice: the artwork is never fully static. Owners may recalibrate a Deck’s density at any point, shifting its appearance from ghostly minimalism to a thick haze of color.

The Power (and Limit) of the Pixel

Asendorf’s broader body of work frequently confronts the nature of screen-based media. Past pieces like Alternate (2023) or Monogrid (2021) relied on custom algorithms to generate perpetually evolving 2D grids. With PXL DEX, that concept migrates into three dimensions. Each Deck embraces the technical constraints of contemporary displays by scaling to the device’s native resolution. Viewers can zoom, pivot, and re-center the animation, revealing new layers of spatial depth and fleeting alignments of light.

However, there is a practical ceiling. Even though the smart contract imposes no strict limit on the number of PXL tokens an owner can deposit, computer hardware does. At a certain point, the system will falter if the rendering load overwhelms a GPU. This interplay between conceptual limitlessness and physical constraint underpins much of Asendorf’s exploration.

A Hybrid of Art Object and Digital Wallet

In an editorial on PXL DEX, curator and writer Kevin Buist captures the project’s dual nature. As he puts it:

“A Deck NFT is a bespoke wallet of sorts, a container for PXL tokens. PXL DEX reduces both fungible and non-fungible tokens to their abstract minimum: a single pixel, a single point of light that can be kept in a virtual box.”

This observation points to the artwork’s broader significance: while PXL DEX can be understood simply as a set of visually enthralling animations, it also acts as a novel framework for digital ownership. A Deck is, in effect, an NFT embedded with its own reservoir of fungible tokens. Collectors become co-creators who can shape their piece over time by adding or removing PXL, reminding us that “possession” in the realm of blockchain-based art can extend far beyond static images.

The Nature of Collaboration

In many ways, PXL DEX offers a built-in system for ongoing collaboration between artist and audience. The formal structure of each Deck is coded by Asendorf, yet collectors have the final word on the actual number of pixels that appear. This model underscores a recurring theme in digital art: code provides a generative blueprint, but its instantiations remain fluid, shaped by both user input and the constraints of technology.

Moreover, this interactive dynamic resonates with the ethos of crypto culture. NFTs initially gained traction by promising verifiable scarcity and provenance; Asendorf takes this further by making scarcity and abundance a parameter that owners can manipulate. Rather than establishing a single, final state, PXL DEX enables perpetual metamorphosis, bridging aesthetics, technology, and the collector’s own sense of play.

Kim Asendorf in Conversation with Fakewhale

Fakewhale: Your work frequently engages with the smallest building blocks of digital imagery. What originally drew you to pixel-level experimentation, and how has that focus evolved over time?

Kim Asendorf: I think I was always attached to pixel aesthetics, ever since my first experiences with digital entertainment systems. Early gaming consoles and the Commodore 64 had a graphic style that felt completely new. It wasn’t like TV, print, or anything else…it was its own world. That aesthetic stuck with me. Over time, I realized I wanted to use computers to create things that were only possible through them. The pixel is the smallest building block, the fundamental unit I can work with, and I like to keep it visible and crisp rather than blending it into larger images. For me, a pixel is an abstraction…it can be anything: a person, an atom, a unit of measurement. It’s fascinating how open it is to interpretation; people see different things in it, but everyone sees something.

The concept of merging an ERC-721 NFT with an ERC-20 utility token is a bold innovation. What led you to the idea of a “deck” that stores pixels as fungible assets?

I’m not sure how often this kind of smart contract setup has been used, but I know ERC-20 tokens have been implemented in artworks before, mostly as utilities, maybe affecting visual parameters, like a volume knob that adjusts an effect. I wanted to take it further, to make something more composable but still retain my authorship. There’s a fine line between making an artwork interactive and turning it into a tool and something that I perceive as an actual artwork. If you add too many adjustable parameters, it stops being my work and becomes more like a platform for someone else’s. I wanted control while allowing variability, so I experimented for years, trying different setups. Eventually, I reduced PXL DEX to a single key variable: the number of pixels. That one element drastically changes how the artwork looks and behaves. This approach made it simple but powerful, while ensuring all the outputs still feel like my work.

In PXL DEX, collectors can deposit or withdraw tokens, altering the artwork in real time. How do you navigate the balance between collector agency and your own creative intent?

My work always mixes conceptual and experimental strategies. With PXL DEX, collectors can remove all pixels, leaving a black screen, or they can add millions. There’s no strict limit beyond the overall supply, but practically, there’s a hardware limitation: GPUs can only handle so much before performance drops. I like playing with those boundaries. The piece is meant to be flexible, something that evolves with time rather than being static from the moment of minting. Collectors can shift its appearance at will, whether keeping it minimalistic for months or changing it later if they feel like it. This flexibility was intentional and is something I want to explore further in the future.

Your past works, such as Monogrid or Alternate, also explored layered, never-looping animations. How does PXL DEX expand or reinterpret those ideas?

I think PXL DEX takes those previous ideas into a more dynamic space. My earlier works played with infinite, self-evolving grids, but they were mostly fixed once completed. With PXL DEX, I wanted to introduce an additional layer of variability where collectors could influence the artwork over time. It’s an ongoing collaboration between the system I designed and the choices made by the owner.

There’s a hardware constraint at play here: theoretically, a deck can hold millions of pixels, but GPUs may struggle beyond a certain point. How do you approach this tension between theoretical scalability and real-world execution?

This is something that fascinates me. I don’t know where the exact limit is yet, and I think that’s part of the experiment. Right now, on my Mac M3, I’ve tested up to five million pixels, and it still runs smoothly. But at a certain point, the graphics card will struggle. That limitation is built into the work. Over time, as computers evolve, the threshold will shift, which adds another unpredictable aspect to the piece. Will consumer hardware continue to get more powerful, or are we already at a plateau? Those are the kinds of questions embedded in the project.

As Kevin Buist put it, each PXL DEX NFT “is a bespoke wallet of sorts, a container for PXL tokens.” How do you envision the role of this “container” evolving as collectors experiment with depositing and withdrawing pixels?

To be honest, I don’t know exactly how people will use it yet. That’s part of the process: putting the work out there and seeing how it lives. It’s an opportunity for people to engage with my work in their own way. That’s also why I asked Kevin to write about it. I wanted an external perspective, someone who could see angles I might not. His interpretation is interesting…he talks about paradoxes in the work, contradictions. I think that’s important. The piece shouldn’t be one-dimensional; it should have multiple layers to explore. The idea of the container is less about the NFT itself and more about the pixel as a token, something that can connect multiple works in the future. PXL DEX is just the beginning, I see this developing into a broader system.

Your work often juxtaposes visual minimalism with conceptual density. How do you navigate that dynamic in PXL DEX?

I think it comes from my early experiments with glitch art. Back in the 2000s, I was really involved in the glitch art movement…people from Chicago and other places were exploring different aspects of it. The thing about glitch is that it’s chaotic and unpredictable. It exposes patterns in digital systems, but you can’t fully control the outcome. Over time, I realized I wanted more control while still keeping some of that raw complexity. That’s why my work now is more “smooth” compared to traditional glitch art: it’s refined, structured, but still retains an element of unpredictability. I use coding and automation to create that balance. I don’t really care how people categorize me, whether as a generative artist or something else, but digital technology is the foundation of everything I do, and I’ve spent over 15 years exploring it in different ways.

Following the success of PXL DEX, what new directions or projects are you currently exploring?

Right now, I need some distance from PXL DEX to clear my head before deciding what’s next. I’ve been experimenting with audiovisual projects, working with a musician to create generative electronic music. I’m also thinking about how to push NFTs further, exploring ways to break their usual structures. I want to see how far I can take them, moving beyond the common assumptions about what they are. For me, the blockchain isn’t just a technical tool, it’s a creative space, and I think there’s still a lot to explore.

fakewhale

Founded in 2021, Fakewhale advocates the digital art market's evolution. Viewing NFT technology as a container for art, and leveraging the expansive scope of digital culture, Fakewhale strives to shape a new ecosystem in which art and technology become the starting point, rather than the final destination.

You may also like

Leander Herzog, Heatsink, WUF, Solo Press Showcase, Basel

“Heatsink” by Leander Herzog, solo press showcase curated by Fakewhale, at WUF Basel, Ba

Tony Cragg: A Journey Through Form and Material

Tony Cragg, a pivotal figure in the landscape of modern sculpture, has revolutionized the domain thr

Roni Horn: A Journey Through the Elements

Roni Horn was born in 1955 New York. She lives and works in New York City.Horn’s artistic producti