Fakewhale in dialogue with: Nestor Siré

We are pleased to present an in-depth interview with Nestor Siré, a Cuban multimedia artist whose work explores the intersection of technology, society, and creativity in the context of the Global South. Through projects related to phenomena such as the ‘Paquete Semanal’ and ‘SNET,’ Siré explores alternative systems of content distribution, documenting and reinterpreting unique and often informal cultural practices that arise in response to social and technological restrictions. With an approach that blends art, research, and activism, Siré offers us a glimpse into the dynamics of resistance and innovation that emerge in contexts of scarcity. In this conversation, we will explore his creative processes, the political and cultural implications of his work, and his perspectives on the future of technology in art.

How did you approach the research necessary to document and artistically represent the phenomenon of “Paquete Semanal”? What were the main challenges in translating such an intricate social practice into a work of art?

The Paquete Semanal is one of the most fascinating phenomena in the Cuban alternative digital landscape. It functions as an informal network for distributing digital content that naturally arose as a response to ongoing internet access restrictions imposed by the Cuban government. It also emerged due to specific conditions and access to media technology, popular entertainment, and the informal economy, as well as the convergence of particular socio-economic conditions, both local and global.

This vast infrastructure spans the entire island and provides access to digital content, including movies, TV shows, music, software, mobile apps, and much more. This data collection is meticulously organized through a careful folder structure that typically totals up to one terabyte per week, housing between 15,000 and 18,000 files. There are “copy points” on every corner of small and large cities where customers can access content via computers to make their media selections, in addition to home delivery services known as “paqueteros”, who ensure content is delivered directly to customers’ homes on physical hard drives. This phenomenon directly or indirectly reaches approximately 10 million users across Cuba.

My family background influenced my interest in these phenomena. My grandfather was one of those involved in the national black-market network for trading and selling romance and western novels, the only form of foreign entertainment available in the early seventies. As access to new technologies spread, the network evolved, maintaining the same human infrastructure but updating the devices and media—from VHS tapes to DVDs and finally to hard drives and USB memory sticks (what we now know as the Paquete Semanal).

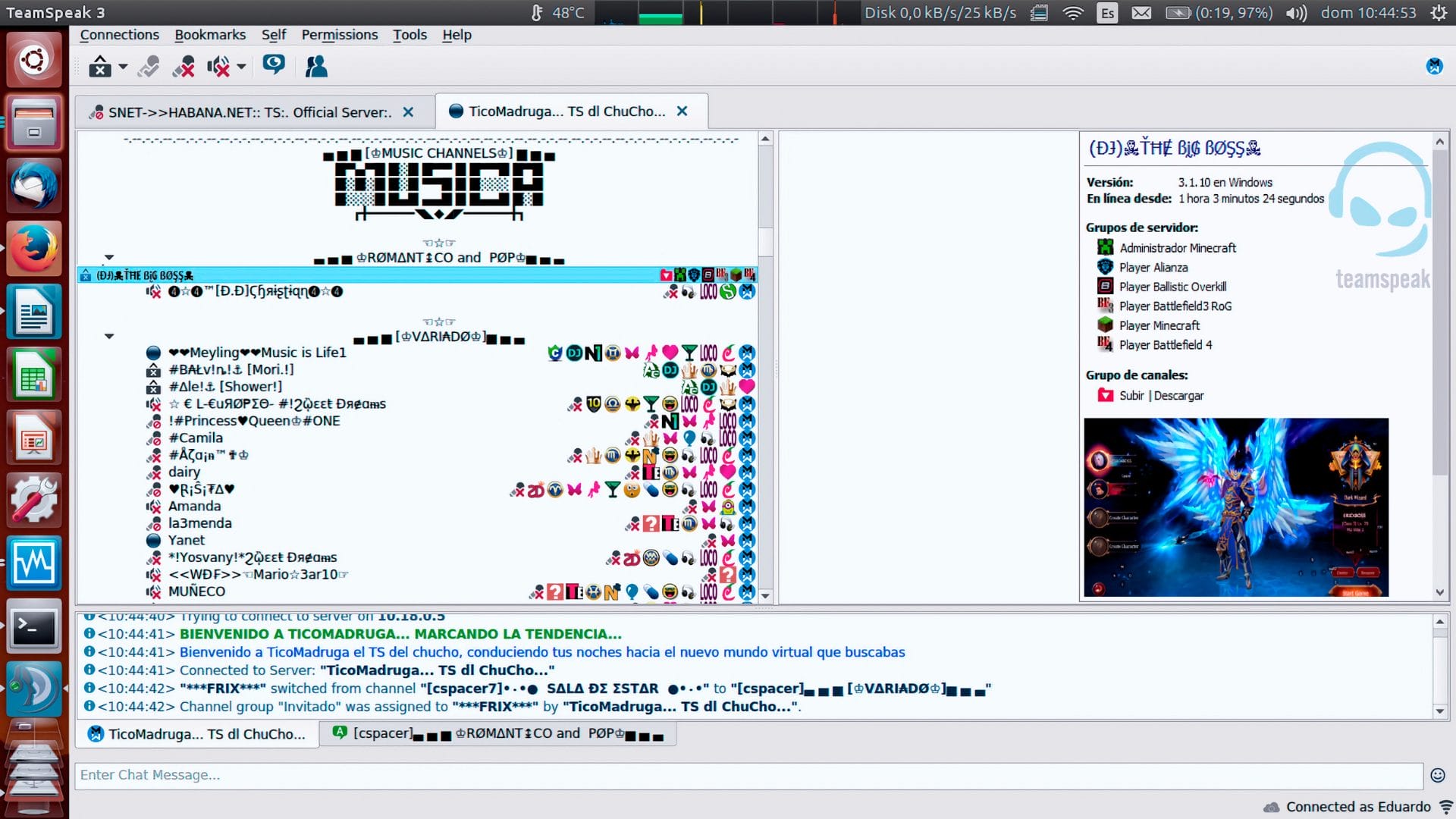

My first project about this phenomenon was CubaCreativa [Video Combos], with which I was invited to participate in the 12th Havana Biennial. It focused on popular creative gestures, behavior patterns, habits, and initiatives that respond to basic needs and even ensure daily survival.

I intervened in informal networks to articulate creative practices and informal distribution methods and use them as a circulation platform for the artwork. For the first time, I collaborated with the so-called “copy points” and launched, over four consecutive weeks, a folder in the Paquete Semanal containing a different combo. In the Cuban digital context, “combo” refers to the practice of selling movies and music on DVDs. These combos are usually a selection of materials with similar themes grouped into a package, allowing consumers to access a variety of entertainment in an economical and convenient way.

I also collaborated with Paquete Semanal managers to develop the aesthetics of the artwork. Estudios Odisea is one of the two main organizations responsible for compiling Paquete Semanal media. With them, I developed the combo systems using the same aesthetics they use for movie combos circulating in the Paquete Semanal. Additionally, I commissioned ETRES, one of the first advertising agencies within the Paquete, to design the catalog of the artwork, referencing the advertisements they created for the first private businesses in the Cuban context after the government eased commercial activities in 2010.

When I created an art section within the folder structure of the Paquete for Video Combos, I opened the door to a new work: !!!Sección ARTE. For seven years, monthly, I shared a wide variety of materials, such as PDFs of newspaper articles, open calls for exhibitions or residencies, books, documentaries, and more. At the same time, I invited Cuban and international artists to present artworks created specifically to be exhibited within this offline digital network, which were presented in a folder named la CARPETA =galería=. !!!Sección ARTE became an offline curatorial project and an exhibition space accessible only through this local informal distribution network.

Although !!!Sección ARTE is the most continuous project related to the Paquete, I believe 17. (SEPT) [Por WeistSiréPC]™ and PakeTown have been the most challenging. For the former, I collaborated with American artist Julia Weist. Together, we visited the most important casas matrices (compilation studios) in each Cuban province, which allowed us to understand the distribution dynamics of this national network. We also gathered digital materials specifically created for the Paquete and discovered changes in the folder structures of each locality.

The centerpiece of this project was ARCA. It compiles fifty-two weeks of the Paquete (64 TB) and is the only large-scale archive of this completely ephemeral phenomenon. Making all this content available to the public outside of Cuba, as expected, is legally impossible. Through the Queens Museum, we established communication with copyright lawyers to explore alternatives. We discovered that a single edition of the Paquete Semanal could result in three life sentences according to U.S. law, which led us to create a publicly accessible catalog with Paquete content. To create this “legal package,” the museum team and I sent thousands of emails seeking permission from the copyright holders of the content that circulated in the Paquete during the week of August 8, 2016. We only managed to secure approximately 10% of the rights under cultural and educational use. To project the remaining content, we developed custom playback software that only played 65% of each video in response to copyright limitations.

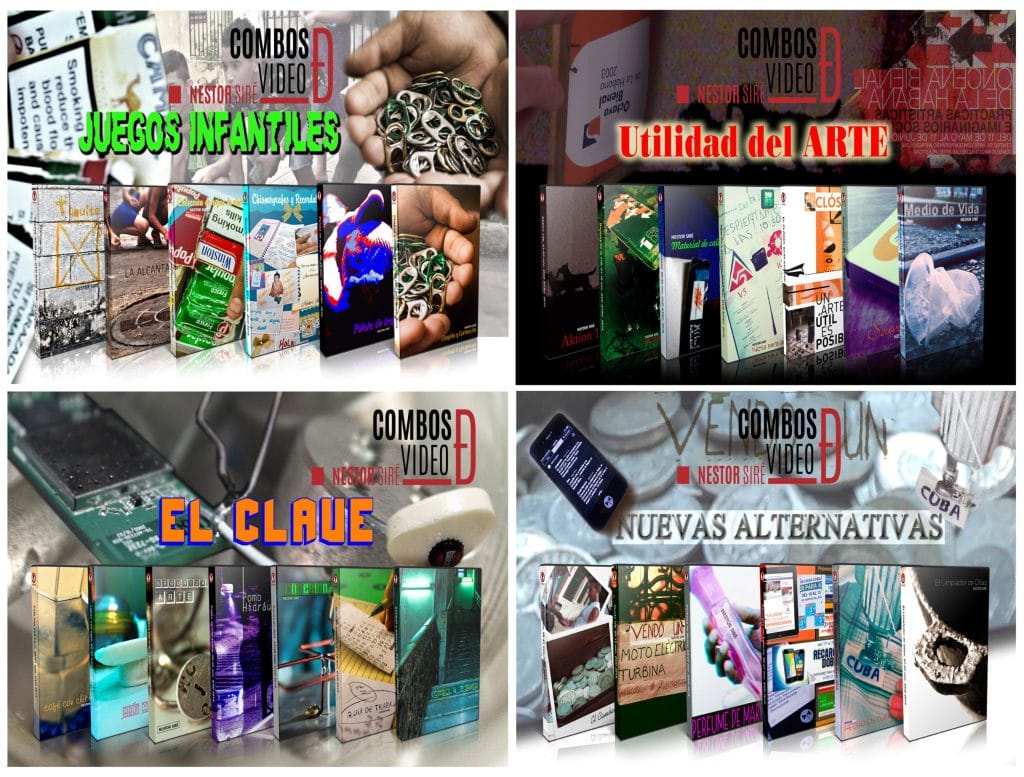

On the other hand, PakeTown channels years of interventions and studies on the Paquete Semanal. This work immerses players in the evolution of Cuba’s informal entertainment media sector up to the Paquete Semanal, in the format of a business simulation game. Conceptually and aesthetically, PakeTown is inspired by the tycoon game genre, such as Pizza Syndicate, FarmVille, and Resort Tycoon, which enjoy immense popularity among Paquete consumers across the island. It was created in collaboration with artist and anthropologist Steffen Köhn and developed by ConWiro, one of the pioneering independent game studios on the island. It is available for both Android and IOS mobile devices and was distributed in the Cuban context through the Paquete. In 2021, we launched a Beta version for Cuban users through a local platform called APKlist. In the first month, more than 10K national downloads were registered. The latest global download statistics from June 30, 2021, to 2023 reached 190K.

How do you think phenomena like the “Paquete Semanal” contribute to the global discussion on access to information and creativity in contexts of scarcity?

We live in a world where the digital environment connects us to a sense of global citizenship, and our virtual coexistence with mobile phones and the Internet is almost ubiquitous. However, our understanding of this coexistence is limited. The political, ecological, and social implications of technology use are not topics of common knowledge. Many of the creative practices born in contexts like Cuba demonstrate a different path from the one presented by large corporations that globalize access to information. I believe that the path of technology should follow the directive of thinking globally and acting locally, with the human being at the center of the equation. Generating a more conscious, active, and flexible use of technology adapted to the characteristics of each context involves embracing diversity and questioning generalized models.

Phenomena like the Paquete Semanal are a good example of how digital infrastructures, when integrated into social life, transform people, and how people, in turn, modify these infrastructures into something new. These social distribution dynamics are so deeply embedded in daily life that we could say every Cuban carries a USB or hard drive with them, potentially making them mobile servers for offline digital distribution.

The Cuban reality regarding digital technological development, in contrast to the low-tech trend that describes much of international production, represents a variant categorized as “necessary.” We are talking about a country with limited infrastructure, where no cutting-edge technology is officially produced or marketed, where there are no funding programs for innovation or research projects related to these topics, and where state monopolies control communication services. This has caused users to shift from being passive consumers of digital networks to becoming active agents and catalysts of their own digital networks and infrastructures, functioning in that intermediate space between offline and online, between cutting-edge technology and DIY adaptations.

The alternative networks in Cuba were not created as an alternative to another reality; they naturally emerged in response to specific sociopolitical situations and a scarcity of infrastructure that met the needs for digital interaction in Cuban society. As a creative social practice, they embody resilience, ergonomics, intelligence, and group cooperation. They continuously find ways to recover and respond to rapid changes in their environment, dynamically reinventing themselves. These networks, connecting hundreds of thousands of users with each other, are proof that there are less polluting and more democratic ways to connect person-to-person. They remove large equipment productions, the complex algorithm systems that control freedom of expression, and the waste produced by corporations that currently control the so-called “future” of technology from the equation.

How do you balance the use of technology with the need to authentically represent local culture in your work? Are there tensions that arise in this process?

In recent years, I have become interested in modeling my artistic projects according to what I call a “human scale.” I develop my projects in contexts that I make close and within communities of which I become a part. It takes time for me to immerse myself in their dynamics and feel comfortable enough to ask the right questions and understand everything surrounding them. On the other hand, in my work, I don’t focus on creating a piece with a predetermined beginning and end. Instead, I establish approaches to certain phenomena or practices and develop multiple interventions. I tend to consider collaborative and multimedia processes in my projects, which, in my experience, allows me to dive deeper into the subjects I am interested in addressing.

I have always been drawn to the fluid relationship between social practices and the creation of individualized and personalized digital infrastructures and technologies, as well as the subversive and creative capacity of individuals in situations with limited access to certain resources. Technology in and of itself doesn’t interest me. Rather, I am interested in a critical approach to technology and in reflecting on its interrelation and interdependence with phenomena that have a social, economic, and political impact.

With CubaCreativa, a project I started in 2014, I have had the opportunity to explore expressions of creativity and technological resilience based on reuse, adaptation, and recombination of resources. I have reflected on practices that are not only from Cuba but also from different parts of the world. Using the Cuban context as a starting point, I have researched from Gambiarra in Brazil to Jugaad in India, the DIY culture of the English-speaking world, and the Japanese concepts of Chindōgū and Urawaza. Each of these represents an approach based on ingenuity and adaptability, a way of experimenting with limited technical resources to achieve functional results.

Currently, in collaboration with Cathy Hsiao, we are developing a special edition of the CubaCreativa series titled PC Gamer [GARRAFA-瓷器]. This project exemplifies how different technological realities are represented in order to connect how these disparate realities form intrinsic parts of a larger global digital economy, an idea we first explored in the “Made in Taiwan” series blending diverse aesthetic practices from Taiwan, China, and Cuba. It incorporates the philosophy of DIY open-source hardware communities into the design of the gamer computer chassis and introduces porcelain, traditionally considered a craft or fine art, into the context of creative DIY gamer modding.

How have you analyzed and represented the aesthetics born from social practices in Cuba? How do you think these practices are shaping new forms of cultural expression?

I have paid attention to the aesthetics that emerge from popular creative gestures, as well as the communities or individuals who generate them, because they are a great source of knowledge for understanding that reality.

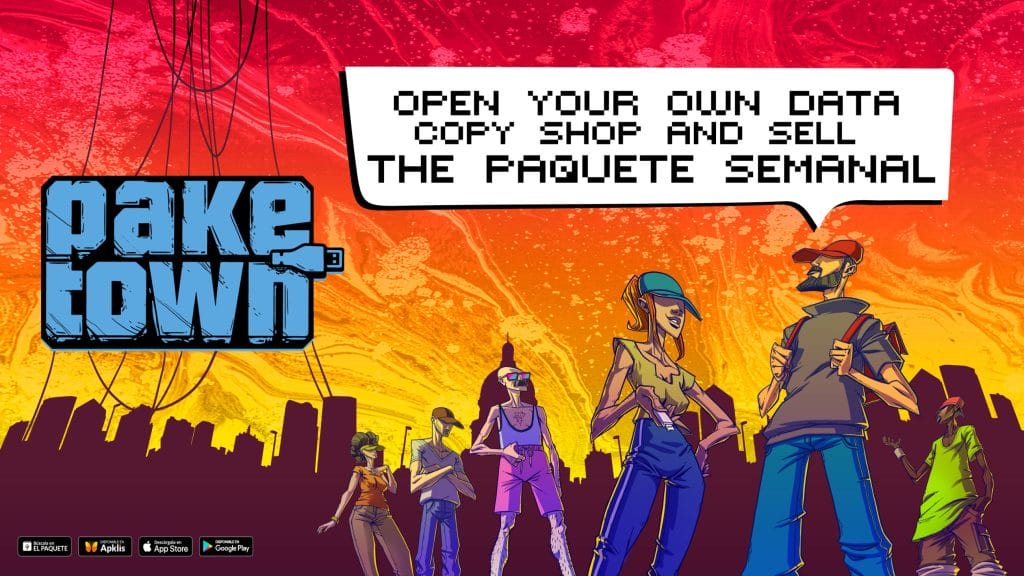

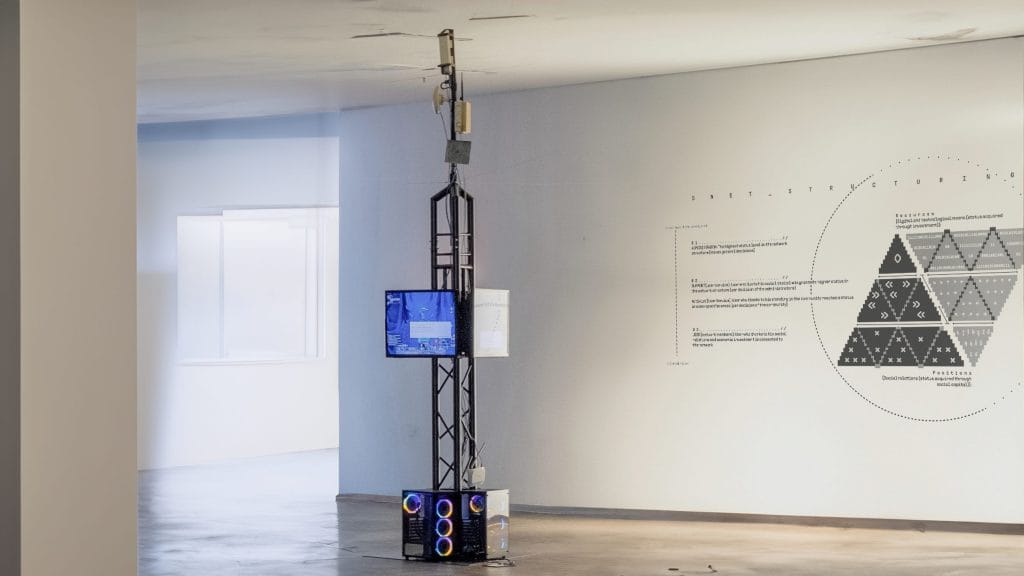

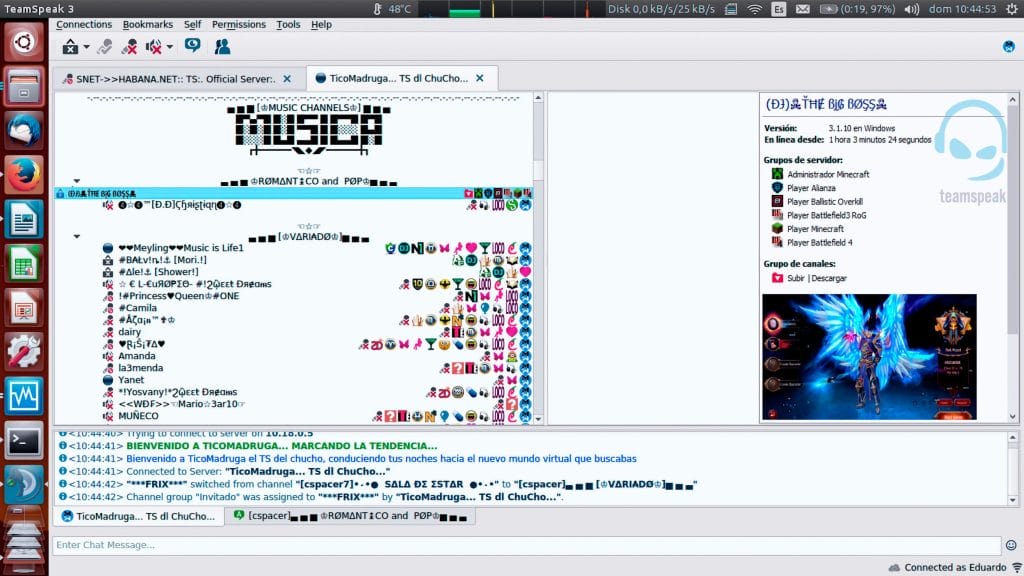

In addition to the Paquete Semanal, there is another phenomenon in Cuba around which I have developed several works. It is a community called SNET (Street Network). This network was born out of an entire generation of young Cubans’ need to play online games in a country where there were no other alternatives for individual interconnectivity. This mesh community network quickly became the largest community network in the world that operates completely independently from the global Internet. It is mainly used as a platform for multiplayer games but also serves as a messaging system, debate forums, file sharing, and local web hosting. Its material base consists of kilometers of Ethernet cables running through streets or balconies and thousands of DIY Wi-Fi antennas mounted on rooftops, network switches, and servers. The existence and functioning of the network depend on the ongoing commitment of a group of volunteers who participate in the creation, management, and maintenance of its hardware and software infrastructure.

In Fragile Connections (in collaboration with Steffen Köhn), I created an interactive installation that faithfully reproduces the technological setup of an SNET node, emulating a fully operational LAN and allowing the public to connect with their smartphones to explore various aspects of this network. This includes a collection of modified video games and multimedia content, SNET’s code of conduct collectively established by its members, and research documents on the community’s history. The collection of research materials includes photographs and videos documenting the hardware infrastructure that supports the network, as well as “screen walk” interviews where users and administrators show different spaces of the network from their own devices. Within this community, a system of digital identity representation emerged, reminiscent of the early days of the Internet, an intermediate point between pixelated icons and profiles decorated with ASCII Art.

SNET has done more than just compensate for the limitations of Internet access in the Cuban capital. It has fostered the creation of new social connections, community dynamics, and languages that shape new forms of cultural expression within Cuban gaming communities.

You have collaborated with various artists and researchers throughout your career. Which collaborations have been the most significant for you, and how have they influenced your work? Can you share an example of a collaboration that led to unexpected results?

I always approach collaborative practices from a horizontal perspective; I find people in different fields with whom I share common interests and advocate for a dialogue that leads to the creative process happening at an intermediate point. Our investigative and creative methods merge in order to share perspectives and achieve a hybrid result. The parties involved share authorship and have rights over the outcome, so each person can use it according to their professional interests in each field.

From a young age, I had the opportunity to develop projects alongside close friends. Chuli Herrera was the first artist I shared projects with while still in art school. However, my first experience developing a large-scale project was with Julia Weist. I often say that Julia and I are like twins in the way we understand art. She visited my studio in Havana, and even though we came from totally different contexts, we instantly felt that we could create something together. Her experience in information sciences and her special interest in studying knowledge and circulation systems allowed us to create projects about circulation phenomena and practices in the Cuban context.

The collaboration that most exposed me to new areas and production processes was Made in Taiwan, in collaboration with Cathy Hsiao. The work explicitly reconsiders iPhone technology from a wider socio-political and material perspective. We analyzed the disparities in distribution, access, and censorship between Cuba and Taiwan and the complexity of our digital identities within the global economy in contrast to the creative social practices. For it, we were interested in not only reproducing an aesthetic from reality but in creating a new aesthetic system utilizing a sampling of easily accessible advanced technologies at that time, incorporating everything from AI platforms for design and DIY plastic recycling practices to produce 3D filament, to the use of traditional porcelain crafting techniques.

Over the past four years, I have developed a series of projects with artist and academic Steffen Köhn. His projects explore the intersection of cinema, contemporary art, and experimental ethnographic research. With Steffen, I have had the opportunity to incorporate an academic perspective into my projects, which helped me ease tensions regarding the research processes within these social practices. All of our collaborative artistic projects have been developed alongside anthropological studies, which have resulted in academic publications. We have also explored the use of fiction and narrative related to digital spaces. The best outcome related to this aspect has been Memoria, a work that blends elements of Cuban reality with fictional storytelling in a retro-futuristic vaporwave aesthetic. Memoria invites contemplation of alternative visions of the Internet, inspiring reflections on a more decentralized, neutral, and non-commercial digital space, much like Cuba’s.

Perhaps Handmade Network has been the most unexpected outcome of my collaborative practice. This is my first art book, co-authored with Steffen, featuring contributions from Bani Brusadin and Erick J. Mota, and published by Aksioma. The book brings together a series of art projects that explore the digital reality within the Cuban context, reimagining these networks as viable alternatives to the capitalist, consumer-driven digital infrastructures controlled by a tech oligopoly that has homogenized the global Internet.

Which artists or artistic movements have had the most significant influence on your practice?

When I think about my references, the greatest artist of all time is Leonardo Da Vinci. The convergence between art, science, and engineering, while one of the foundations of his later recognition, was also the cause of his lack of understanding in his own time.

Among Cuban artists, two are my key references. What fascinates me about Félix González-Torres’ work is the clarity with which he understood that cultural production and socio-economic reality go hand in hand. The “soft power” with which he addresses complex social issues, that perfect balance between the personal and the public, art as experience and interaction, the pragmatic and the emotional, all deeply resonate with me. On the other hand, Tania Bruguera is an artist of great depth in her actions. She handles and defends the role of the artist outside conventional art spaces in a critical, political, and civic sense. Her Arte Útil manifesto changed the way I understand art.

I closely follow the careers of Eva & Franco Mattes, Aram Bartholl, and Simon Denny, with whom I’ve had the opportunity to meet and share in exhibitions. The Mattes’ commitment to investigating the darkest and most real spaces of the Internet and the simplicity with which they share their projects deeply inspire me. Aram showed me that large-scale communities can be created from the field of art. Denny is my best example of intervention and representation of the corporate world, and the role of the economy, geopolitics, and the current development of technology.

As a young artist, the concept of Relational Aesthetics by Nicolas Bourriaud influenced how I see art, especially in understanding the role of the artist. I believe that through art we can challenge dominant narratives. I’m drawn to artists who provoke rethinking of stereotypes and imaginaries, who question “the truth,” and who deconstruct memory, reality, the freedom of technology, and the democracy of information from their own realities.

How do you believe alternative platforms for the circulation of visual culture are redefining the idea of cultural distribution in Cuba? What can we learn from these informal networks that could be applied to more globalized contexts?

I don’t think we should idealize or romanticize these practices too much. The reality is that with access to global technologies and platforms, it is likely that these alternatives will gradually disappear. Sometimes, we fail to consider the power that the cultural imaginary of technological and digital development in the so-called “First World” has on shaping expectations. That’s why I’m more attracted to the idea of the alternative path; not only because it’s the solution in the absence of certain services or resources, but because it offers the possibility of imagining a different version of what is understood as the future.

When we stop to consider contexts like Cuba, we tend to associate them with isolation and limited access to information. But we shouldn’t forget that historically Cuba has been a space where the gray market has thrived, traces of which can be tracked back to the smuggling networks of the 17th century, an escape valve against the trade monopoly imposed by the Spanish metropolis. The Cuban Revolution and the Cold War heightened isolation, but information distribution networks never ceased to exist, facilitated by travelers and people with internet access who shared digital content. These were then distributed through the already existing human networks and infrastructures, from hand to hand, person to person.

These circumstances have given rise to common local archiving practices; all Cubans are like mobile local servers sharing information through a pocket USB or our own mobile phone or personal computer. We generally maintain databases on multiple formats and digital storage media. I believe it’s a more sustainable, resilient, and modular way of storing digital media that significantly reduces the ecological impact and energy consumption of large data banks.

In my opinion, the first step would be to denaturalize the relationship with technology, to transform interaction and adapt it to your needs in a critical and active way. While we are surrounded by a frenetically hyperconnected world, in Cuba it’s still common to voluntarily decide when to connect and when to disconnect, which provides a very uncommon sense of balance. Perhaps without realizing it, we have created the conditions for a very different kind of technological life in this world, which could be of great use.

How do you see the evolution of technology in Cuba and its impact on artistic production? Are there any new technologies or trends that you plan to explore in your upcoming work?

For years now, cryptocurrencies have been present in the Cuban context as a mechanism for international transfers and payments on online platforms. With the rise of NFTs, one of the most solid communities in Latin America was even created. Although these technologies promise a future of digital freedom, decentralization, and security, the reality is that multiple profiles of Cuban artists were removed from major NFT markets like OpenSea due to the United States’ embargo policies against Cuba. This is why it becomes ironic and contradictory to associate phenomena like blockchain technologies with Global South contexts, as we have, on the one hand, Web 3.0 limiting access to users from countries like Cuba, and on the other hand, a myriad of speculative practices offering fleeting economic lifelines disguised in pyramid schemes.

For better or worse, the reality is that blockchain technologies are here to stay, and in countries like Cuba, where access is through VPNs using fake profiles, they offer more reliable alternatives than the officially available financial systems.

During the launch of PakeTown in various Cuban cities, Steffen and I first noticed the widespread popularity of Axie Infinity in the Cuban context. Practically overnight, a large part of the Cuban gaming community embraced the game. In Axie Infinity, players breed, collect, battle, and trade digital pets to earn income in the cryptocurrency used by the game. The “play-to-earn” game became popular during the COVID-19 pandemic in many Global South countries, where the income earned through it often exceeded the average national salary. At its peak, the cheapest team of three Axies cost about 1,000 USD. This gave rise to a parallel economy where companies and individuals offered “scholarships,” lending Axies to players who couldn’t afford the initial costs, under the condition of sharing a significant portion of the profits. Player guilds emerged worldwide, offering training sessions and holding entrance exams for scholarship applicants. However, it soon became apparent that many of these economic agreements had an exploitative nature.

The first action we took regarding this phenomenon was Axie Gamer Cooperative. Steffen Köhn and I created a scholarship system that offers a circular economic structure, where scholarship recipients are granted co-ownership of the team along with 60% of the earnings, with the remaining 40% allocated to a common fund dedicated to acquiring a new team, which would be offered to another player under the same conditions. This introduced a cooperative model of collective ownership that differed significantly from the extractive agreements commonly found in the guild model.

We are currently in the process of developing the research project The Social Life of Crypto, which examines how cryptocurrencies have become integrated into everyday informal economic practices in countries on the margins of financial and technological power. The project will bring together a research group formed by the PI and two postdocs who will conduct fieldwork in three locations where cryptocurrencies have emerged as a key tool for alleviating economic hardship: Cuba, the Philippines, and Kenya. This process will take at least three years and will form the basis of an artistic action, as well as multiple publications on the topic.

fakewhale

Founded in 2021, Fakewhale advocates the digital art market's evolution. Viewing NFT technology as a container for art, and leveraging the expansive scope of digital culture, Fakewhale strives to shape a new ecosystem in which art and technology become the starting point, rather than the final destination.

You may also like

Göksu Kunak, Bygone Innocence at Pilevneli Gallery, Istanbul

“Bygone Innocence” by Göksu Kunak, curated by Léon Kruijswijk, at Pilevneli Gallery, I

Curator Spotlight #1: A Focus on Contemporary Chinese Digital Art

We are excited to announce our new format, “Curator Spotlight,” with Giuseppe Moscatello

Fakewhale in Dialogue with Oliver Hull

Oliver Hull is an artist who skillfully blends art, technology, and critical reflection on complex t