Fakewhale in Dialogue with Mathias Pöschl

Mathias Pöschl’s work transforms mechanical processes and simple materials into two-dimensional pieces that evoke a certain painterly sensation. Mathias takes us into a world where repetition and error become central elements of artistic creation. We had the pleasure of engaging in dialogue through this interview to explore the details of his creative processes and the reflections that emerge from his meticulous and meditative work.

Fakewhale: Mathias, your works often feature errors and imperfections that arise during the copying process. We’d like to know how you transform these flaws into significant elements of your pieces and what role they play in your practice.

Mathias Pöschl: Since I’ve always been interested in the phenomenon of copying – I started out doing photorealistic pencil drawings –, it was a consequent step to at one point start working with the photocopier as the primary source for my works. Whereas I once tried to produce something with my hands that looked machine-made, I now try to explore the painterly properties of a machine. It took me a while to realize and accept that the imperfections of the process are the real essence of the work. I do not have to do any transformational work for them to have significance – they are just there.

Your choice of simple materials and economical methods is evident. What attracts you most to using such materials, and how do they contribute to your artistic vision?

It seems like pairing a diy-approach with perfectionism is what I`m fated to do. I’m not one to have an idea and go let it produce by someone else. You don`t need high-end camera equipment to investigate the nature of image-making. Using so-called cheap materials and processes may have started out due to financial reasons, but it has become a sort of principle by now. It`s often the simplest things that lead to the most interesting questions.

Which artists or movements most influence your work, and how do these influences manifest in your pieces?

A lot of my research of former years revolved around Minimal Art and the stuff that went on in the world (especially the US) at the same time. I wanted to find a way to marry minimalist principles with political content and failed in a somewhat fruitful way. I would describe my later works as the illegitimate children of Frank Stella and Wade Guyton.

How has your training at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna influenced your artistic approach, and which teachings or experiences have been most significant for you?

My years at the Academy in Vienna were characterized by the two most valuable things a teacher can give: freedom and time. Having a studio space that was accessible 24/7 allowed me to experiment and learn to appreciate failure as an integral part of the process. After abandoning studying philosophy because I wanted to do something with my hands, something material, it felt like the perfect situation. I could continue to do my reading, had better opportunities for discussions with teachers and colleagues and I got to do what felt like real artistic work for the first time.

How have contemporary critics and theories influenced your artistic practice?

In a bad way. I consumed a lot of theoretical work in former years and tried to incorporate it quasi-directly into my own work – a futile attempt. Nowadays I like to keep them kind of separated, reading theory (and more and more fiction) to loosely accompany my practice. Also, I am not a very up-to-date person and have an inbuilt mistrust against the latest trend – I like to be late to the party, read my Foucault and dabble in semiotics.

You use the photocopier as your primary tool. Can you tell us how this mechanical device affects your artistic practice and the creative possibilities it offers?

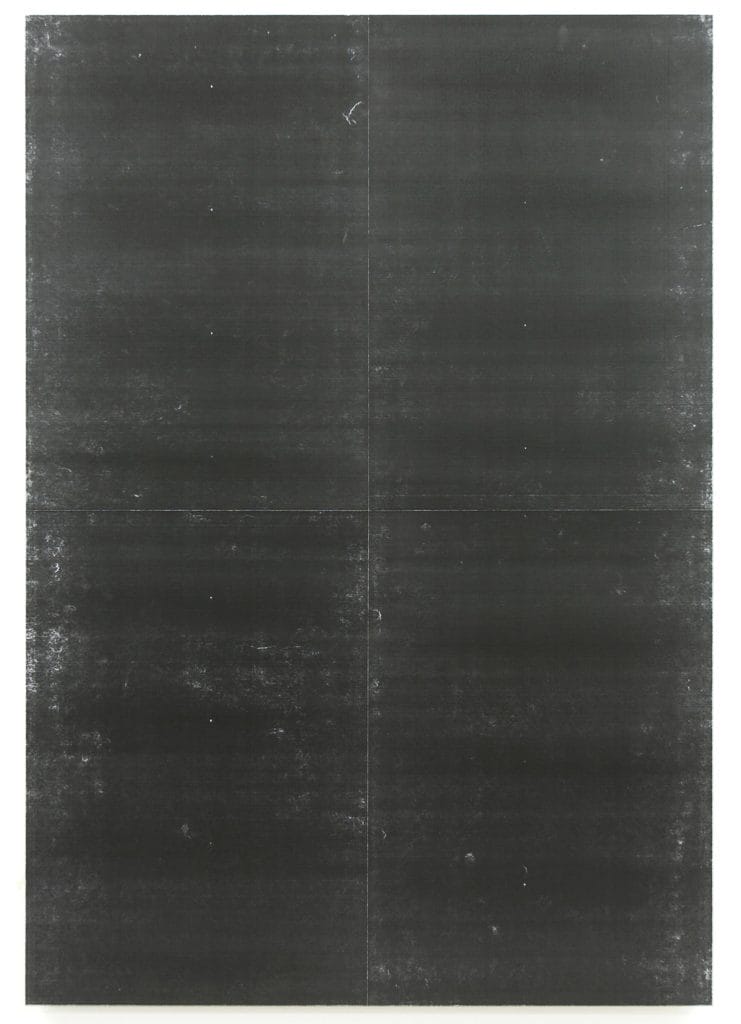

Starting to work with the photocopier fundamentally changed my approach. Whereas once I was trying to find out about the structure of images by doing the copying myself, now I can go at it from the other side. Getting rid of any references and starting out with a totally black page that gets copied over and over allowed me the freedom I had lacked in older works. The creative possibilities the device offers are very limited, if there are any at all. That`s where the work can start.

The concept of “disciplined redundancy” seems to be central to your work. How do you balance repetition with uniqueness in each of your pieces?

That’s right – I seem to be a very repetitive and disciplined guy when it comes to my work, doing things over and over diligently lies at the heart of my practice. Plus, all of my works come in series.

That`s why the use of the photocopier was such a revelation to me – it does exactly that. And it opens up a whole field of interesting questions about the status of the original, uniqueness, redundancy, exactness and perfection. Repetition is the only thing that’s unique.

Your practice includes the removal of toner to create abstract forms. Can you explain the process behind this technique of “negative painting” and how you approached it?

My basic process is to diligently glue 4 or 16 sheets of copied A3 paper onto a coated chipboard panel. During this process, imperfections and small structural flaws become more visible due to small amounts of toner being shifted around. Realizing the potential of the toner to be removed, I started to directedly clear areas of the surface, trying to investigate the opportunities of painting by removing – instead of adding – paint. The resulting pieces feature rudimentary compositions of very simple redoubled forms.

In your more recent works, you use drawing programs to create shapes to be manually transferred. What is the role of digital technology in your practice, and how does it influence your creativity?

Almost all of my works originate digitally. I like the exactness and the mutability the screen affords in the sketching process. In a way, the digital sketch could be seen as the finished piece in its perfect version, but accepting that is a step I have yet to take – the intrigue the manual process offers and the three-dimensional object it yields are too tempting.

In your production process, how do you manage the transition from the digital creation phase to the manual phase, and what challenges and steps do you encounter during this transfer?

As I mentioned, the digital version might be seen as the perfect version of the finished piece – absurdly, the work is perfect before the real work begins. Taking it off the screen and confronting it with material realities – that’s where all the trouble and all the fun starts.

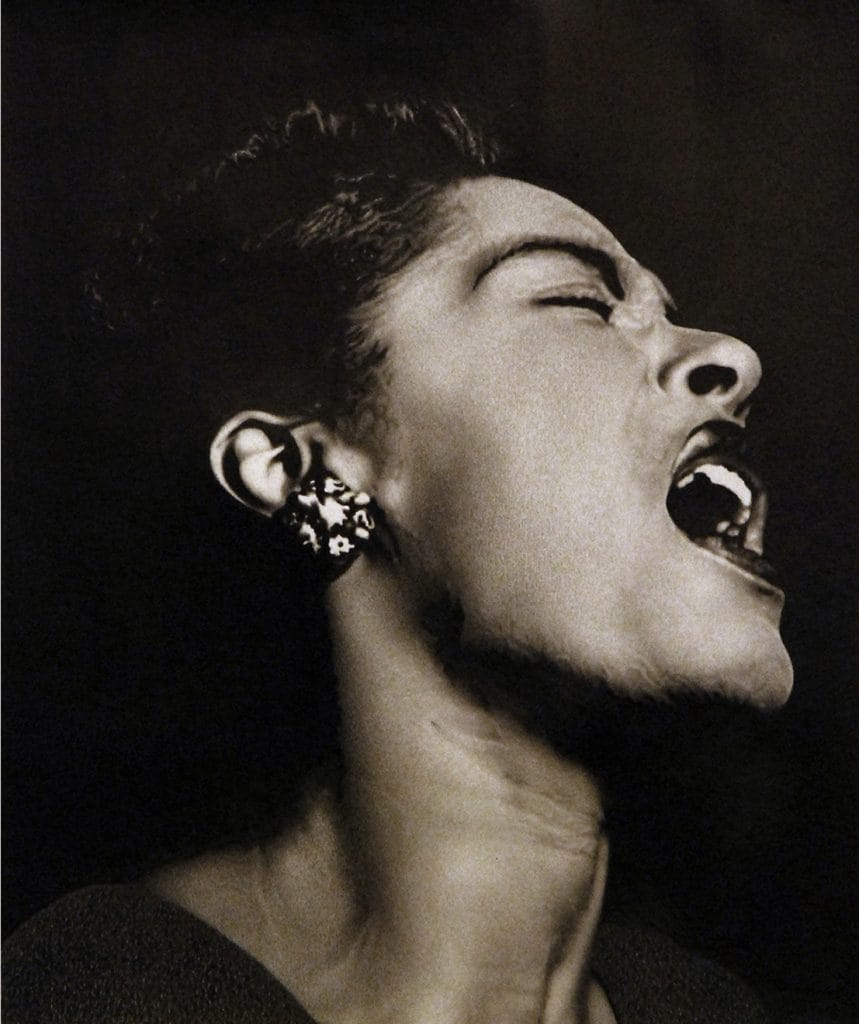

1You recently started working on paintings based on the cover of a 1984 poetry publication by Eldridge Cleaver. What inspired you in this project, and how does it relate to the recurring themes in your work?

I acquired the little booklet in 2017 and have been drawing copies and variations in colored pencil on its cover ever since then, using them in some smaller works. It’s a remnant of my interest in the 60ies in the US and all their implications and a reminder to myself how slow my working process sometimes needs to be.

Looking to the future, what new techniques or materials are you curious to explore, and what directions do you think your art will take in the coming years?

For some time I have been trying to find ways to incorporate photography into my process, so I will keep on going in that direction. And maybe I will find the heart to do a wholly digital work some day. But, knowing myself, I don’t think so.

fakewhale

Founded in 2021, Fakewhale advocates the digital art market's evolution. Viewing NFT technology as a container for art, and leveraging the expansive scope of digital culture, Fakewhale strives to shape a new ecosystem in which art and technology become the starting point, rather than the final destination.

You may also like

Nathan Carême, Le point neutre at La Station, Nice

“Le point neutre” by Nathan Carême, at La Station, Nice, 13.12.2024 – 17.12.2024.

June Crespo – SOLAR: Galería Ehrhardt Flórez

There’s a subtle but decisive difference between “looking inside” and “seeing through.” En

“The Gatherers” at MoMA PS1: Where the Superfluous Stares Back

“The Gatherers”, 24 April – 6 October 2025, MoMA PS1 (Long Island City, New York, USA), cura