Fakewhale in dialogue with Georg Eckmayr

We’ve been following Georg Eckmayr’s work for some time, fascinated by his ability to intertwine the physical and digital worlds, exploring the contradictions and ambivalences that arise from this interaction. Through his multimedia installations and research, Eckmayr not only challenges traditional notions of perception and identity but also reflects on the complexity of contemporary digital culture. FakeWhale had the privilege of speaking with him, delving deeply into his creative process and his vision for the future of art and research.

Fakewhale: The theme of contradiction is central to your work, described as a “productive force.” How do these ambivalences and contradictions manifest in your installations, and how do they affect the audience’s experience?

Georg Eckmayr: There are several examples of this approach. First, in my film Open Water, multiple narratives are condensed into a single storyline. Philosophical reflections and technical language merge, creating a rhythmic stream of thoughts. Each viewing can evoke different references, depending on whether you focus on one aspect or another. I aim to immerse the audience in a multifaceted experience that reflects the true complexity of our world. Too often, this complexity is overlooked, reduced, or even suppressed in favor of simplistic explanations. My goal is to challenge this narrow perspective and encourage the audience to move beyond the illusion of a singular reality, dismantling the simplistic, monocausal view that overlooks life’s richness and interconnectedness.

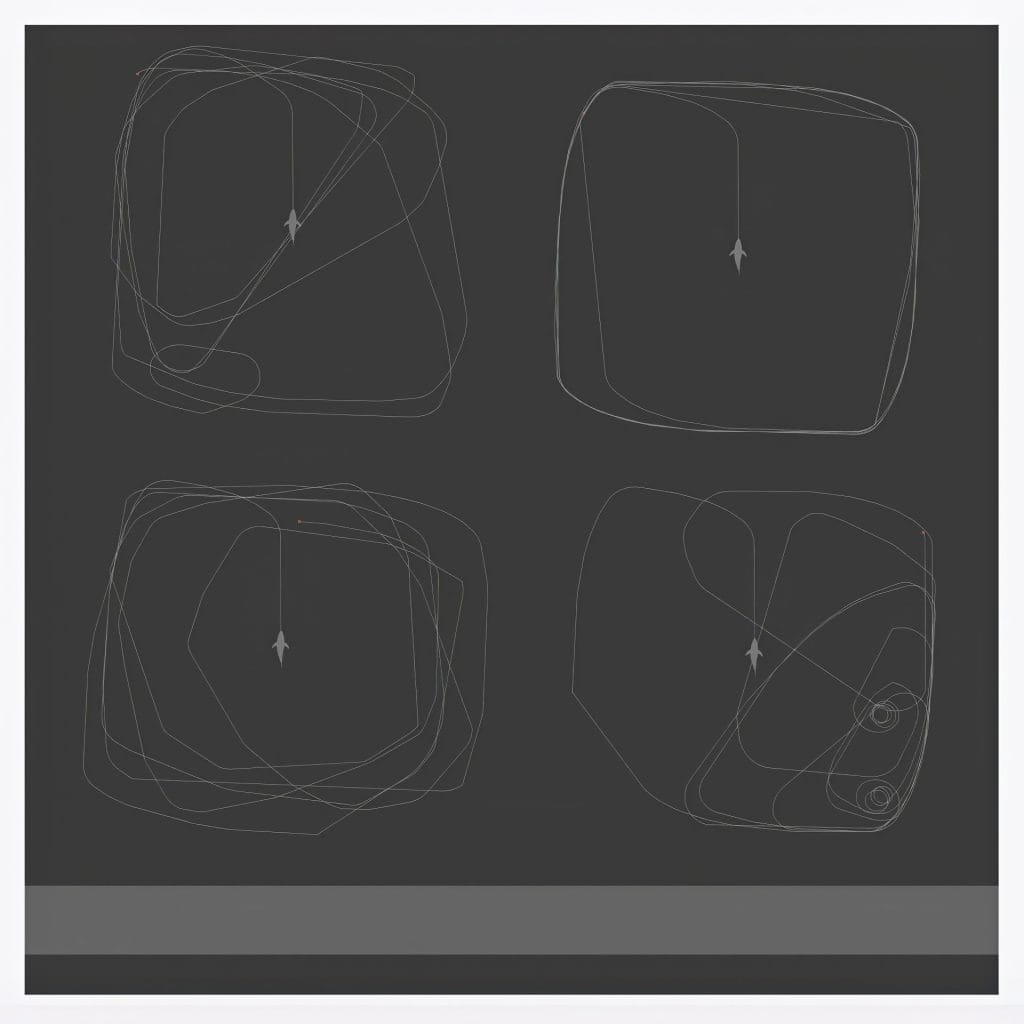

Another example could be the installation Relics from the Internet, where the contradiction exists at the material level. Even if drawn by a machine, the drawings appear hand-made, with slightly shaky lines, yet the precision of the geometry evokes a distinctly digital feel. This interplay between the organic and digital creates tension, challenging our perception of authenticity and craftsmanship.

Your work seems to play with the boundary between the physical and the digital realms. How do you approach the dialogue between these two worlds in your artistic practice, and what inspired you to explore their entanglement?

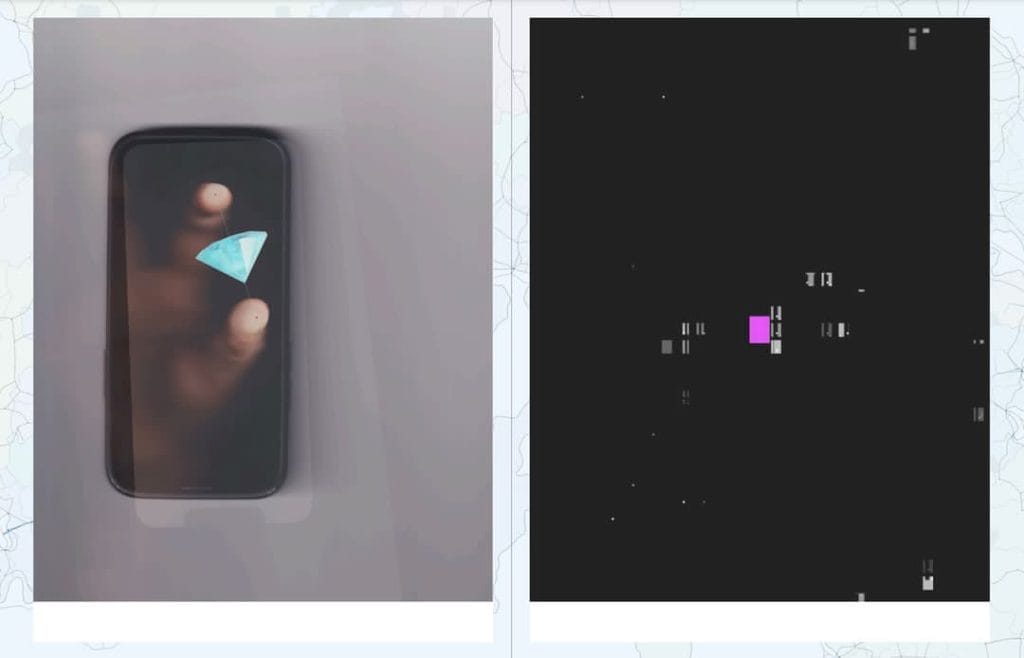

I’ve been working with computers since I was ten, and I’ve always been fascinated by the unique pace they bring to my creative process. In the digital realm, time operates in cycles and loops, unlike the continuous flow we experience in the physical world. This discrepancy between temporal landscapes inspires me. Most digital devices aim to minimize this, smoothing out the quantitative aspects and feedback loops of digital processes. However, I believe we should feel this discrepancy and experience how hybrid communication shapes our physical social practices and our human perception of meaning. A good example here is my work, gestures – songs of algorithm. Though it exists as a networked sculpture in the digital realm, the audience experiences and interacts with it through a device, where the light on the screen becomes a physical manifestation of the work itself.

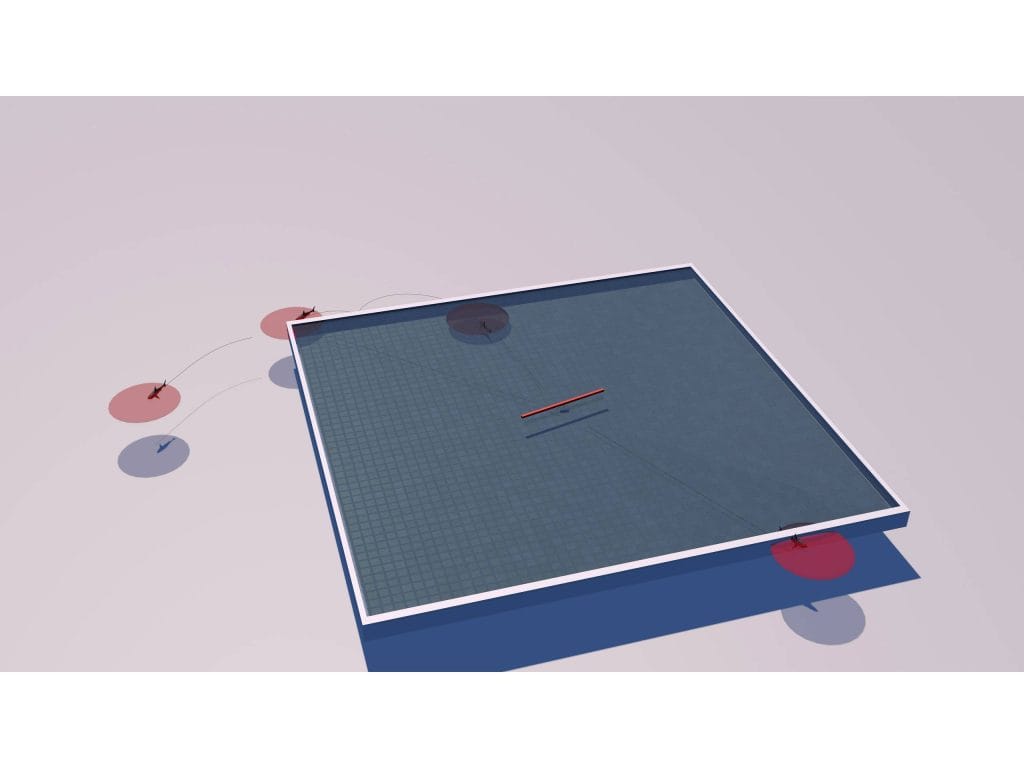

When approaching the dialogue between the digital and physical world in my work, I often begin with digital elements – an algorithm, a short video clip or a digital geometry. This forms the core idea, which must then be aesthetically defined so the audience can distinguish between what is ‘work’ and ‘non-work.’ In this process, I carefully consider how the audience will interact with the piece and the kind of experience I want to create for them. I need to determine if, and which, physical manifestations of the work should be experienced – or whether the work should be experienced at all. For example, at the core of the The Digital Ability to Perceive Walls project is an algorithm I developed. While the code of the algorithm and the working algorithm itself remain invisible, it can be experienced through various manifestations of the work.

Your networked sculpture “gestures – songs of algorithm” is designed to adapt to various exhibition contexts, from white cube environments to more informal social settings. What were the technical and conceptual challenges in creating a work that is so flexible and adaptive?

The most challenging aspect, technically and conceptually, was figuring out how to create a cohesive composition from independent elements – how to make them appear as a unified form. Early in the development process, I realized that achieving frame-locked synchronization at a technical level is only feasible with high-end setups, like syncable media players in a LAN network. Even with a standard PC, it’s difficult to deliver more than six perfectly synchronized video streams across six screens. Yet, I aimed to create an adaptive composition of up to 20 pieces suitable for even informal contexts.

From my early experience as a VJ, I learned that music and visuals can align harmoniously without strict frame-locking, as long as the right material is chosen. And even as John Cage, John Zorn, and others have demonstrated, music isn’t about perfect synchronization but about the temporal fitting of events. Ultimately, I adopted this approach. I crafted 17 pieces that share a common timebase, all aligned to 120 frames per second. Each loop varies in duration, from 12 frames to 2400 frames, yet all align to the common timebase. When played, these pieces form a cohesive composition regardless of whether they start at the exact same moment or play in perfect sync. This approach is especially effective for facilitating audience interaction. My goal was to create a modular artwork suitable for any context. The audience should be able to experience this work not only in a hardware-intensive white-cube setting but also on their own devices, making it adaptable to any social context.

In “The QUANTS – A Profile Pictures Choir”, you created a choir of digital entities existing between human gestures and the digital realm. What is the meaning behind this “choir,” and how do you think it interacts with the notion of identity in an increasingly digital age?

What if PFPs (profile pictures) were not just static representations of our identities, but could gain independence and develop their own agency? I imagined PFPs growing tired of their passive role as mere avatars and engaging in human-like actions. Singing and forming a choir felt like an appropriate form of protest against their otherwise meaningless existence. I chose the choir because it is a cultural form commonly used in religious and ceremonial contexts. It integrates individuals into a larger collective while fostering a sense of social cohesion. Mostly it is the goal of a choir that participants collaborate harmoniously to create this unified whole. To adapt this cultural form to modern times I appreciate that my choir is notably multi-vocal.

What fascinates me about digital identity practices is that the medium itself becomes part of the message. How do I present myself on Instagram or X? There is a rich culture here, personally authored, but shaped in part by digital processes, corporate interests and attention-market logic. We integrate these dynamics into our modern sense of self – whether we realize it or not. This process deserves deeper reflection.

You explored landscape in “a generic landscape,” a work that analyzes and interprets data from the web to recreate images. How do the internet and collective perception influence your representation of the landscape?

I was invited to participate in a festival in the Tyrolean Alps, a region renowned for its pristine nature and untouched mountain landscapes. To prepare a piece for the festival, I began by conducting web research on the area, which unearthed thousands of postcard views – generic landscape portraits saturated with clichés. It was this cliché aspect and the local population’s identification with “their” landscape that I wanted to explore. I wondered: what if I subtly altered these familiar landscapes? Would they still function as projections of a collective identity? To investigate this, I used GAN networks to recreate the images, generating scenes that closely resemble the original postcard clichés but with subtle distortions in scale or materiality. For instance, a 2,400-meter-high peak might suddenly take on a Himalayan appearance, disrupting its identificatory power. Initially, I was unsure whether the locals would appreciate my modifications, but I was pleasantly surprised by their enthusiasm to experience familiar views through a new digital lens.

Your piece “The Digital Ability to Perceive Walls” raises fascinating questions about digital perception and boundaries. How did you develop the concept of an artificial intelligence that perceives limits, and what do you think this means for our understanding of intelligence and consciousness?

The core idea I explored was: what are limits and boundaries? They don’t simply exist by being stated; they take shape through our practices and interactions. Boundaries are largely social phenomena, so I began to question how we perceive them. Can a simple algorithm be taught to perceive walls? What would it require? I was looking for the simplest realization of a perceptive agency and then got inspired by the early cybernetic experiments with agents capable of finding their way through labyrinths. The first finding was that there is not much intelligence necessary for tasks like that, simple relays could produce this effect, but there needs to be an intention to do so. Perception cannot exist without intention, which drives and shapes the process of information retrieval. This intention is not typically an inherent part of the perceptual system’s functioning but rather emerges from external influences.

Contemporary AI systems like LLMs cleverly connect corporate interests, the intelligence of engineers and the intention of prompting users with a vast data pool of possible outcomes. But do these systems perceive? Do they show intention to communicate with us without being prompted? What we refer to as ‘artificial intelligence’ is not an independent, intelligent subject, but rather a hybrid system combining multiple forms of intelligence driven by various intentions. There is no singular conscious entity within the machine that possesses the intention or intelligence to engage with us – it’s a network of various sometimes conflicting actors working together.

Your animated film “Open Water” has received attention at several international festivals. How do you approach cinematic storytelling compared to static installations, and what themes are you exploring in this particular work?

The key difference between installing works in space and the cinematic approach for Open Water lies in the control over time. Open Water operates within a clearly defined time span, whereas installations allow the audience the freedom to explore at their own pace. Installations, in this sense, function as loosely structured spatial texts. I enjoy the creative freedom of crafting spatial texts, but some ideas are better suited to the fixed time frame of cinematic narratives, which excel at building atmosphere and provide a meticulously crafted dramatization of the audience’s experience.

Coming from a storytelling background, I have a deep appreciation for cinematic narratives – the structure, the characters, the mystery that unfolds. However, I’ve always found linear storytelling to be too rigid for my vision. My work often requires more condensation and abstraction. With Open Water I aimed to integrate multiple narrative structures within a single film, creating a landscape of potential meanings rather than a clear, linear storyline.

On the themes: Open Water is based on my artistic research project The Digital Ability to Perceive Walls and centers around the creation of an agency that perceives limits as its main narrative. This theme intersects with other narratives in political discourse, such as automated mass surveillance and the balance between national sovereignty and individual freedom. I was intrigued by the social pragmatics of boundaries and borders, the behaviorist utopias emerging from digitally networked communication, and particularly by the excessive, imaginary surplus that emerges from rigid definitions.

In your research on technical images and digital perception systems, you mentioned the use of affect theory and systems theory. How do you integrate these theoretical approaches into your artistic practice, and how do they influence your creative process?

In many of my works, particularly The Digital Ability to Perceive Walls, Open Water, or THE BUG, I employ a post-human aesthetics approach. My aim is to move beyond an anthropocentric perspective, treating human and non-human actors on equal footing. This approach feels essential in a world where our techno-social environments heavily influence our understanding of what it means to be human. These theoretical concepts provide an ideal framework for exploring this perspective.

These concepts focus on systems rather than individual human subjects. I’ve always found this perspective useful when engaging with digital culture, where many typical human characteristics important for communication – such as facial expressions, a singular body-bound presence, or a clear distinction between individuals and groups – are less relevant. In digital spaces, it’s often unclear whether the entity I’m interacting with is a fellow human or a bot. Shifting the focus from clearly defined entities to systems and their characteristics provides a more accurate understanding.

Affect theory, in particular, moves beyond simple cause-and-effect models by introducing affect as a kind of void that generates effects without the need for a clearly defined cause. These theoretical frameworks have deeply influenced my worldview, helping me navigate and challenge human-centered biases.

The project “False Memory Syndrome” explores the possibility of documenting events that never occurred. What conceptual challenges did you face in attempting to represent absence or falsehood in a documentary context?

I was initially asked to document a performance event, which unfortunately couldn’t take place due to pandemic restrictions. Despite this, I decided to move forward with the work. I gathered as much material as possible from the planned performances – sketches, emails, drawings, and images – and then visited the site where the event was supposed to happen. The images of the empty space became the stage upon which I ‘staged’ these materials, interpreting what could have unfolded.

A false memory syndrome lets you remember something that did not happen. That experience was exactly what I was seeking. The challenge was to do justice to the originally planned works, which never happened. My aim was not to create a falsehood, but to fill the absence with potential. I didn’t want to impose too much of my own interpretation on the other artists’ intentions. To avoid this, I carefully researched their backgrounds, studied their body of work, and reflected on why they chose the specific location to stage their performances. It felt like a delicate process of walking in someone else’s shoes. In the end, the artists were all genuinely pleased with my film, which, for me, stands as a tribute to the ephemeral nature of performance art.

In many of your works, such as “Relics from the Internet”, you use algorithms to create robotic drawings of objects found online. How do you think this process of automation and digital appropriation redefines the notion of authorship in art?Delegating the creation of artwork to others is a common practice with e.g figures like the Fluxus artists in the 1960s or Jeff Koons today using skilled craftsmen to produce their work. According to Foucault’s notion of the ‘author function,’ authorship becomes detached from personal practices and is instead shaped by consensus and collaboration.

Utilizing robots, artificial agents, or found online footage introduces a new form of consensus. These mediums require translating my creative intentions into terms that machines can understand. The resulting work becomes a hybrid of my original vision, the technical possibilities (affordances), and the often hidden motivations behind the technology’s availability. Understanding the data, resources, and practices that enable my artistic process is crucial. In my view, authorship is fundamentally about responsibility: I am accountable for the work I produce and can be held responsible by others.

In your work “they are mine!”, you address the issue of power through the algorithmic reconstruction of biometric data. What is your conceptual aim with this piece, and how do you think technology is redefining notions of control and ownership?

they are mine addresses the freedom to download and repurpose any data from the internet. Being present on digital networks exposes you to various vulnerabilities. Everything shared publicly – your photos, the images you’ve taken, your words – can be repurposed by anyone, often distorting the original intent. The traces you leave behind, including your personal data, are potentially harvested by dubious actors, then used or sold in opaque ways. Participating in the digital public sphere means relinquishing control over your data, and you’re rarely aware of how it’s being exploited. In my work they are mine, I assume the dubious role of extracting data from the internet to exert a form of control over the individuals depicted. While claiming control over these powerful public icons holds emancipatory potential, it also means that parts of me may be owned and used by others to control me.

Digital technology is on the brink of transforming not only our notions of ownership and control but also the entire social fabric. Digital automation enables mass surveillance on an unprecedented scale and influences our communication and social practices through algorithmic affordances and recommendations. Ownership, a core function of our society, is also being reshaped by digitalization. We are shifting from traditional ownership models to subscription-based systems, while big data collectors claim ownership over the data of our daily lives. On the other hand, digital technology holds the potential for public empowerment. It challenges the concept of the nation-state by fostering global communities and provides individuals with digital tools for organizing protests, amplifying public opinions or for open access knowledge production. As artists and researchers, we bear responsibility, we must contribute to shaping this transformation in a positive direction and address and reflect this topics in our daily practice.

In “Iconic Landscapes,” you explored irreversible transformations of iconic images. What is the significance of these transformations, and how do you think they influence the collective perception of places and symbols deeply rooted in the cultural imagination?

This work focuses on the mechanisms of digital pattern recognition and leverages these approaches for aesthetic intervention. I wondered whether a color scheme alone carries iconic qualities. To some extent, it does. My topological transformations of the images distorted their representational aspects, but the color scheme remained recognizable. Although the specific references of the images were obscured, the color scheme – a pattern – still provided some clues about the genre from which they may have originated. In my view, understanding how digital pattern recognition algorithms work is crucial, as they are widely deployed in technologies from self-driving cars to plant recognition apps and will significantly influence human perception over the long term.

In your latest project, “Beyond the Hype: Into the Unknown”, which will be released on foundation.app, you explore interaction with the blockchain platform. What led you to work in this new context, and how do you perceive the impact of NFTs on digital art?

This project is not my own, but rather an online group exhibition curated by Unknown Collector featuring works from their digital art collection. I’m delighted to be included with my work. However, I have several projects exploring interactions with blockchain technology.

My fascination with decentralized systems, cryptography, and new methods of community organization has long fueled my interest. Although I’ve been interested in blockchains since 2015, I started working with NFT technology more recently. I minted my first collections – RESCUE, Quants, and Untitled Me – starting 2022, and am currently preparing to mint the gestures – songs of algorithm project. The moment I minted my first work, I realized a whole new world had opened up. My artistic practice has always been deeply rooted in digital realms, and suddenly, I felt liberated from the need to transfer my work into physical forms. Even many examples of early net art, shown on PCs or laptops in galleries, never fully detached from its physical, exhibited context. With NFT technology, this seemed possible for the first time. New formats, such as GIFs, JPEGs, and short MP4 loops, suddenly became valid forms of art. And especially for my work essential, the screen presenting the works is no longer a conceptual part of the work. I am fascinated by the concept of network sculptures existing primarily in digital realms, with physical instantiations only occasionally provided for audience interaction. I am excited to explore this further.

Looking at your practice as both an artist and a researcher, how do these two aspects of your work influence each other? Has your academic research ever led you to discover new territories for your artistic production?

My research practice is in many cases invaluable for the conceptual development of my art. For example, in the The Digital Ability to Perceive Walls project, I was particularly intrigued by the systemic nature of algorithms. Initially, there was a concept for a perceptive algorithm, but no clear idea for an artwork. The artwork subsequently developed within the theoretical context.

Generally my artistic and research practices become more and more entangled. Not only does my research shape my art, but it is often true vice versa. Both are different methods of thinking. Whereas academic research mostly looks for generalized truths, artistic approaches focus on specific aesthetic qualities and characteristics of a certain phenomena. My work represents an intersection between these two. On the one hand I use my research as a tool for testing the conceptual robustness of my artistic work and providing ongoing inspiration about current topics in digital culture. On the other hand my artistic approaches help to reflect practical aspects of theoretical hypotheses.

You have collaborated with other artists and technologists in the past to create projects like “A Landscape of Me”. What do you look for in a collaboration, and how do you balance the creative dialogue with the need to maintain your artistic vision?

Collaboration can challenge and inspire creative routines, but it must be founded on mutual respect for each other’s strengths. It’s crucial that ego does not interfere; the focus should be on achieving something collaboratively that could not be accomplished alone. Collaborating with technologists and artists offers distinct experiences. With technologists, I often have the primary control over the artistic results and can be very open about any approach throughout the process. However, working with fellow artists is especially rewarding, as it challenges and enriches my own artistic practice. For me, artistic collaboration means that the final work should reflect both artistic visions. Typically, it becomes clear from early discussions whether this is feasible. If discussions revolve around logistical details like individual wall space in the first meeting, it may signal that genuine collaboration is unlikely. Effective collaboration should be more than the sum of its parts. If we can find a common narrative that entangles both artistic perspectives, I am eager to pursue it.

Looking to the future, which emerging technologies or themes fascinate you the most, and what will you focus on in your upcoming projects?

I am currently working on my new short film, RAW Material, which is part of the broader project RAW material & DATA gestures. This project also encompasses the networked sculpture gestures – songs of algorithm. My artistic research explores the possibility of building communities without relying on traditional human or machine language. It investigates a common ground that unites humans, machines, and creatures of any kind. I find the medium of timing particularly promising for this inquiry. Consequently, I am interested in understanding how communities are shaped through tactile and time-based forms of communication. I plan to explore these topics not only in the mentioned film but also through my work with networked sculptures as I delve deeper into the genre.

fakewhale

Founded in 2021, Fakewhale advocates the digital art market's evolution. Viewing NFT technology as a container for art, and leveraging the expansive scope of digital culture, Fakewhale strives to shape a new ecosystem in which art and technology become the starting point, rather than the final destination.

You may also like

Nick D’Alessandro, Sprocket at LVL3, Chicago

Sprocket by Nick D’Alessandro, curated by Liam Owings and Luca Lotrugio, at LVL3, Chicago, 03/

Fakewhale Solo Series presents Vantalight by A.L. Crego

On April 10th, Fakewhale Gallery’s Solo Series is set to unveil “Vantalight” by A.