Invisible Structures: Dan Graham and the Shapes of Critical Thinking

Dan Graham never followed a conventional artistic path. He didn’t attend art school, nor did he receive formal training in the traditional sense. And yet, he became one of the most influential artists and thinkers of the late twentieth century. His journey began in 1960s New York, a time when art was breaking free from its formal constraints to become language, system, and process. In this fertile, shape-shifting context, Graham opened the John Daniels Gallery in 1964, at just 22 years old. The gallery lasted only a few months, but in that short span it hosted seminal exhibitions by then-emerging artists such as Sol LeWitt, Donald Judd, Robert Smithson, and Dan Flavin. Graham observed, listened, absorbed, and, most importantly, he wrote.

His earliest steps into the art world were not as an artist but as a cultural critic and perceptive observer of social systems. His first texts, published in magazines like Arts Magazine and Harper’s Bazaar, focused on advertising, suburban architecture, television language, always with a sharp eye that blended sociology, philosophy, and aesthetic intuition. In this sense, Graham was one of the purest examples of conceptual art, not because he replaced objects with ideas, but because he interrogated the structures through which we perceive and construct reality.

One of his most emblematic early projects was Homes for America (1966–67), a series of photographs taken on bus rides through New Jersey, accompanied by a critical text reflecting on suburban uniformity and its embedded ideology. The work was published not as an exhibition, but as an article in Arts Magazine, already a radical gesture. The artwork didn’t inhabit the gallery, but the printed page. The magazine itself became his “white cube.” This was a key move that would define much of his practice: art not as a visual object, but as a conceptual apparatus for observing systems.

This is how Graham entered the orbit of conceptual art, though always from the margins, never adhering to orthodoxy. He didn’t call himself an artist, nor was he interested in “producing artworks” per se. Rather, he sought to dismantle the invisible architectures, visual, linguistic, social, that shape our everyday experience. It was the beginning of a hybrid, critical, participatory practice that would later unfold through video, performance, architecture, and interdisciplinary collaborations.

Interfaces Between Public and Private: Photographic and Textual Experiments

Between the late 1960s and early 1970s, Dan Graham delved into the tensions between public and private space, between observer and observed, and between medium and message. Through a series of works that combined photography, diagrams, text, projections, and performative actions, Graham didn’t merely represent reality, he fractured it, reconfigured it, and exposed its hidden frameworks.

One of his most emblematic works from this period is Present Continuous Past(s) (1974), an installation using a mirror, a video camera, and a monitor with a slight delay. Upon entering the space, the viewer sees themselves reflected in real-time through the mirror while simultaneously watching a delayed version on the monitor. Time is split, and the sense of self is caught in a feedback loop between present and past. The piece doesn’t illustrate time; it embodies it. It becomes a perceptual machine that transforms the viewer into a participant, constantly oscillating between subject and object.

Other works, such as Schema (1966) and Detumescence (1969), employ the language of bureaucracy and standardization, forms, statistics, measurements, to question how identity and desire are structured. Schema, for instance, consists of a printed sheet describing itself through purely technical parameters: number of lines, font size, paper quality. It mimics the language of objectivity, yet in doing so reveals its own constructedness. The piece becomes a mirror of systems that pretend to be neutral, yet shape everything they touch.

These works aren’t meant to be “looked at” in the traditional sense. Instead, they function as tools to examine systems of observation themselves, how we see, how we are seen, and how we are conditioned by external structures: architecture, media, pornography, advertising, science. Graham didn’t stand outside these systems; he operated within them to expose their contradictions.

The viewer, in this context, is never passive. They are implicated, often physically, within the dynamics of the work. Here we see the early emergence of one of Graham’s most enduring ideas: that vision is never innocent. It is always shaped by power, space, and social context. His early experiments are blueprints for a lifelong inquiry into how we see, and how that seeing sees us back.

From Video to Performance: Body, Spectator, and Media

In the 1970s, Dan Graham shifted his focus toward video and performance, not as a break from conceptual rigor, but as a means to embody it, literally. If his earlier works destabilized perception through mirrors, text, and photography, his turn to performance brought these tensions directly into the space of the body, his own and that of the viewer.

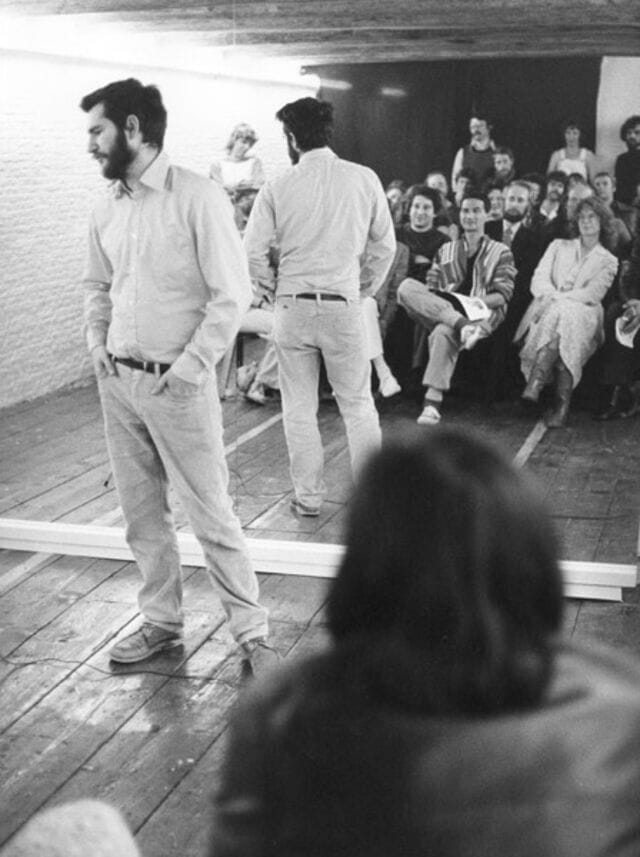

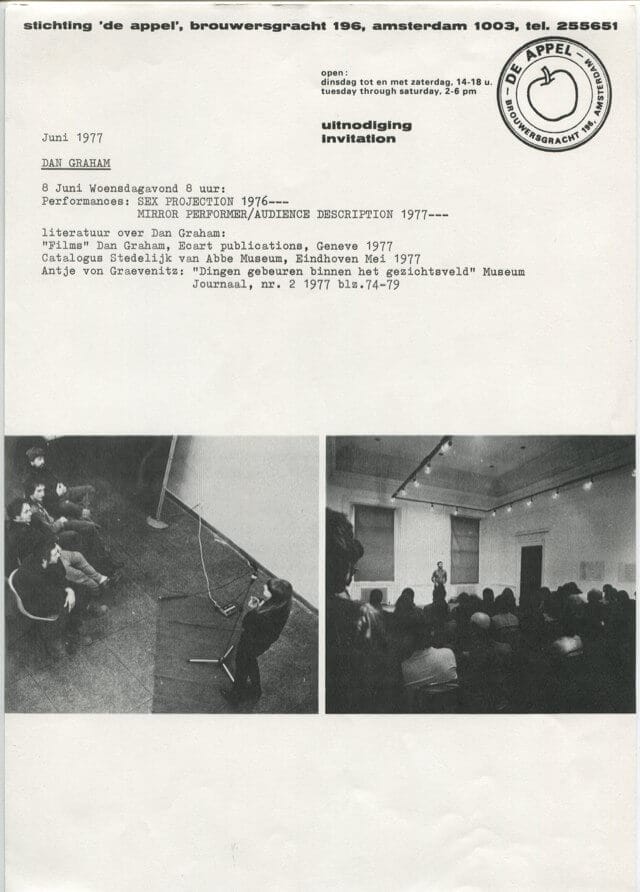

Video, for Graham, was never just a tool for documentation. It was a critical medium, a perceptual extension, a space where time, image, and body collided. One of his most iconic works from this period is Performer/Audience/Mirror (1975), a performance in which he stands before a mirror and begins describing his actions in real time. Gradually, he shifts to describing the reactions and behaviors of the audience, who see both themselves and Graham reflected back. What unfolds is a subtle but intense negotiation of self-awareness and alienation, a mise-en-scène of roles, expectations, and psychological dislocation.

Unlike performance artists like Bruce Nauman or Vito Acconci, Graham wasn’t invested in psychological exposure or personal catharsis. His performances were structural dissections, designed to reveal the implicit codes of behavior, control, and representation. The body became not a site of expression, but a node in a larger network of spatial, social, and technological relations.

This logic extends to his video works, many of which were shot in suburban environments or sterile interiors, featuring slow camera movements and voiceovers that evoke a sense of quiet surveillance. In these pieces, the viewer becomes a voyeur of systems, not of narrative action. Yet in Rock My Religion (1982–84), Graham opens up to a more layered, narrative approach. The video juxtaposes the ecstatic rituals of 19th-century Shaker communities with the visceral energy of punk and rock music. Patti Smith becomes a prophet figure, and the garage concert becomes a space of collective transcendence. Music here is not background, it’s ritual, ideology, and cultural code.

In both video and performance, Graham reframed the very idea of the artwork. No longer an object to be consumed, but a field of relations, a temporary condition that implicates and transforms its audience. His work is not about showing; it is about activating perception. It’s not about presence, but about destabilizing presence.

Graham’s stage was never neutral. It was a mirror, a trap, a system, one in which the viewer, willingly or not, became entangled.

Pavilions and Transparencies: Architecture, Psychology, and Public Space

From the 1980s onward, Dan Graham’s work turned increasingly toward architecture as medium, not as construction, but as experience, perception, and social behavior. His pavilions, constructed in glass and steel, sit somewhere between sculpture, functional structure, and psychological device. On the surface, they evoke the clean geometries of modernist design, Mies van der Rohe, corporate lobbies, garden conservatories, but Graham’s pavilions are anything but neutral.

Built from reflective, transparent, or semi-transparent glass, these structures manipulate vision and interaction. One sees through them, into them, and back at oneself. The viewer is no longer a passive observer, but a participant in a shifting visual system. Your reflection overlaps with others’. Boundaries dissolve between inside and outside, subject and object. Perception becomes unstable.

In works like Two-Way Mirror Cylinder Inside Cube (1981) or Public Space / Two Audiences (1976), Graham explores how architectural environments encode asymmetries of visibility. The two-way mirror becomes a metaphor for power: you may observe without being seen, or be seen without knowing it. Transparency, in this context, is not openness, it’s control.

His pavilions dismantle the fantasy of modern architecture as a utopia of clarity. Instead, they reveal how built environments organize behavior, identity, and access. These are not monuments. They offer no message, no central point of focus. They are sites of negotiation, changing with light, time of day, number of visitors. They are activated only by being used, walked through, mirrored within. The audience doesn’t look at the work; they move through it, become part of it, get lost in it.

Crucially, Graham redefined the idea of public art. No longer a static object placed in a plaza to signal cultural prestige, but a relational space that exposes how we behave in shared environments. His pavilions invite discomfort, reflection, intimacy, confrontation. They are not aesthetic destinations, they are social mirrors.

By refusing to offer a fixed interpretation or function, Graham’s structures embody his core belief: that architecture, like art, is always ideological, and that true critique comes not from distance, but from inhabiting the system and bending it into something else.

Collaborations, Influences, and Cultural Crossings

Dan Graham’s work was never isolated; it thrived on dialogue, contamination, and exchange. From the very beginning, his practice existed at the intersection of disciplines, visual art, architecture, music, critical theory, media studies, blurring lines that others treated as borders. He was not just an artist, but a cultural cartographer, mapping the infrastructures that shape how we see, behave, and relate.

Among his most impactful collaborations were those with musicians and performers. His iconic video Rock My Religion (1982–84) is a prime example of how Graham read music not merely as sound, but as ritual, social construct, and psychological force. The video draws parallels between the spiritual fervor of 19th-century American Shaker communities and the raw, ecstatic energy of punk and garage rock. Patti Smith emerges as a postmodern shaman, embodying a secular spirituality that channels collective desire. For Graham, music wasn’t illustration, it was sociopolitical content.

He also collaborated with architects and artists on public structures, working not to beautify space but to interrogate its logic. Even when engaging professional architecture studios, Graham maintained a critical distance. His pavilions, though impeccably constructed, were never “design.” They were instruments of perception, asking how space shapes behavior and how glass reflects ideology.

Graham’s influence spans generations, from conceptual artists of the ’70s to today’s practitioners of media art, installation, and relational aesthetics. His prescient exploration of surveillance, feedback loops, and viewer participation has become foundational for artists working in interactive, immersive, or post-digital contexts. And yet, Graham never followed trends. He carved his own path—unapologetically rigorous, often ironic, sometimes elusive.

Equally vital was his role as a writer and thinker. His essays, ranging from semiotics to pop culture, from suburban planning to minimalism, embody the same structural clarity and layered complexity found in his installations. He wrote as he built: to dismantle systems from within.

Ultimately, Graham’s practice can’t be confined to a medium or movement. His work was about crossing thresholds, between disciplines, roles, and systems of meaning. What he leaves behind is not a style, but a method: one of embedding critique into experience, and of using every medium, be it mirror, video, or voice, to reveal what lies behind the image.

Critical Legacy: Dan Graham Today

Dan Graham passed away in 2022, leaving behind a body of work that continues to resonate far beyond the historical context in which it emerged. His legacy isn’t defined solely by the pavilions scattered throughout public parks around the world, nor by the works housed in museums or the videos screened in retrospectives. It is most profoundly felt in the critical unease he was able to provoke, an unease that feels more urgent today than ever.

We live in an era where transparency has become a dominant rhetoric, from open-plan architecture to the myth of total visibility on social media. Yet Graham taught us that transparency is never neutral. His reflective spaces and perceptual games warn against the illusion of “innocent” seeing. Every gaze is situated; every act of looking is also an act of exposure. In this sense, Graham anticipated many of the questions we now face around digital surveillance, identity performance, and the spectacle of everyday life.

Even the very notion of public art underwent a radical transformation thanks to him. No longer a commemorative monument, but a device for collective inquiry. His pavilions do not offer refuge or beauty, but complex, often disorienting experiences that compel those who enter them to reflect on themselves, on others, and on the shared space between. This is not art that decorates, it activates. Not art that consoles, but that complicates.

For contemporary artists, especially those working across installation, media art, relational practices, and institutional critique, Graham remains a model of intellectual rigor and creative freedom. He never bowed to market logic, nor did he simplify his thinking for the sake of accessibility. On the contrary, he cultivated a layered, ironic, sometimes uncomfortable practice, always grounded in ethical clarity.

Dan Graham created a body of work that doesn’t merely exist in space, but deconstructs it; that doesn’t simply occupy time, but unsettles it; that doesn’t offer truths, but embodied questions. His most powerful legacy lies in this capacity to problematize reality rather than represent it. Today, more than ever, we need that clarity.

fakewhale

Founded in 2021, Fakewhale advocates the digital art market's evolution. Viewing NFT technology as a container for art, and leveraging the expansive scope of digital culture, Fakewhale strives to shape a new ecosystem in which art and technology become the starting point, rather than the final destination.

You may also like

Weiyu Chen, “Restraned Desre, 2024,” at HEAD-Genève, Geneva.

“Restraned Desre, 2024” by Weiyu Chen, at HEAD-Genève, Geneva, 30/01/2024. Exhibition T

Inside WUF Basel 2024: A Premier Press-Only Event for Contemporary Creative Culture

Every year, Basel becomes the focal point for the world’s leading journalists and art enthusia

Anne Imhof: Breaking Boundaries

Anne Imhof, born in 1978, has emerged as one of the most compelling voices in contemporary performan