Banks Violette in Conversation with Jesse Draxler hosted by Fakewhale

Banks Violette is an American artist whose sculptures and installations mine the aesthetics of black metal, punk, and subcultural extremity to interrogate violence, erasure, and existential collapse. Born in Ithaca, New York, his trajectory—from personal struggles including addiction, to his status as a cult figure in contemporary art—mirrors the themes embedded in his work: destruction as a form of creation, mythology as both a refuge and a trap. His practice fuses minimalist rigor with the visceral intensity of subcultural iconography, distilling chaos into stark, almost forensic compositions. Violette’s art does not merely depict societal disenchantment; it implicates the viewer, collapsing the divide between observer and participant, forcing an encounter with the seductive pull of nihilism, spectacle, and collective complicity.

In this conversation, Violette and Jesse Draxler dissect the psychological gravity of extreme environments and the mechanisms that bring his work to life, whether through decayed luxury, the searing intensity of black metal, or the fractured aesthetics of subcultural mythologies. Their dialogue explores Violette’s engagement with fabrication, the evolving relationship between underground culture and digital reach, and the personal cost of navigating an often ruthless industry. They also reflect on the impact of physical detachment from urban centers, considering how solitude fosters a deeper, more intimate engagement with the creative process.

Banks Violette vs. Digital Tools

Disclaimer: The following interview is a summary of the spoken conversation and not a verbatim transcription.

Before delving into his most significant works, Jesse raises how Violette’s large-scale pieces often first meet audiences in a two-dimensional realm, like in the golden age on Tumblr or more recently on Instagram, sparking curiosity about whether Violette himself uses digital processes.

Jesse Draxler: I was very often on Tumblr, and your work was everywhere. That’s how many people discovered you, digitally. Do you ever use digital means yourself, or is that just not your style?

Banks Violette: I think about things in purely sculptural terms…mass, weight, gravity…and there’s no analog for that in a virtual space. I’m not resistant to digital tools; I just don’t see how they help me realize certain physical elements. At the end of the day, I’m mailing foam-core models and toothpicks, because I have to literally see how it all works in real life. It’s a ‘caveman approach.

While digital renderings help collaborators grasp his vision from afar, Violette insists that true comprehension of his installations, be it a burned church or a collapsed chandelier, only materializes through direct physical confrontation.

Jesse Draxler: Still, I use VR sometimes and wonder how your immersive installations, like that burned church at Whitney Museum, would translate. Imagine stepping inside it virtually; it could be mind-blowing. Have you ever considered that?

Banks Violette: I like that idea in principle, especially if you look at something like the Whitney church…these burnt skeletal remains cast in salt, floating in darkness. Digitally, it reads almost liminal, like a VR environment. But for me, mass and weight and gravity are crucial. I can’t replicate that sense of real, physical presence in a headset. Still, I’m not against VR; I just don’t see how it captures the full scale and material impact I’m after.

Complicity, Destruction, and the Whitney Church

A recurring concept in Violette’s practice is complicity, the notion that once you engage with violent or disturbing imagery, you share responsibility. Jesse seizes on this idea when discussing Violette’s famed Whitney church installation, probing where the line lies between aestheticized violence and moral involvement.

Jesse Draxler: You’ve talked about complicity; when we see destruction, part of us can’t help but watch. Where does art end, and real-life horror begin? How do you push viewers to question their own role, especially in something like the burnt church at the Whitney?

Banks Violette: There’s always that moment where you’re watching something…a tragedy, a disaster, and part of your brain goes, ‘watch it burn.’ When I did the Whitney church installation, the sound, the light, the burned skeletal remains of the church floating in black space… it wasn’t about spectacle. It forced people to acknowledge their own engagement. Nobody gets off easy. Beyond just the spectacle, there’s this whole tradition of ruined sacred structures, like in German Romanticism, or even photographs of bombed-out cathedrals in World War II, that people find strangely beautiful. So when these black metal kids in Norway burned churches, it tapped into the same uncanny fascination with destroyed religious space. You realize how complicit you are the moment you think, ‘Wow, that’s gorgeous.’ The Whitney church installation had that same effect: it forced people to confront their own fascination with ruin.

He also references collaborating with a musician from the Norwegian black metal scene who’d been directly involved in criminal acts. Rather than glamorizing violence, Violette wanted to confront the audience with its willingness to find aesthetic value in destruction, and to ask how culpable we become when we’re drawn to that imagery.

Collaboration with Celine: Collapsed Chandeliers

Shifting from cataclysmic imagery to high fashion, Violette’s 2022 collaboration with Celine placed shattered chandeliers in Paris and Tokyo; a collision of decayed opulence with Hedi Slimane’s sleek design.

Jesse Draxler: Those chandeliers were all around the internet. How did that project come about, and how did you adapt your ruins-meets-luxury angle to something as global as Celine?

Banks Violette: I’ve known Hedi Slimane since his Dior days. I did some drawings for him, then he proposed this ‘around the world in 30 days’ thing with collapsed chandeliers. We had some digital tools, but I was still shipping foam-core mock-ups, like, ‘Make this.’ Letting go of total control was new for me, but seeing that ruinous aesthetic in a high-fashion context was fascinating.

Even in a luxury brand collaboration, Banks Violette reverts to physical prototypes over intangible renderings.

Jesse Draxler: Okay, so like those first chandeliers, I remember seeing them a long time ago. Did you just make those first ones yourself out of experimentation, and then learn a way to produce them, manufacture them?

Banks Violette: The way I used to work, and this probably has to do with a lot of, like, lack of trust for other human beings, was that I did carpentry, machining, metalworking, welding, mold-making, you name it, all in-house. Which is great when you’re in your thirties and on a lot of drugs, but I’m fifty-one and my back hurts. I realized I had to figure out workarounds because it’s a crazy, unrealistic thing to do forever. Part of why I did it was not trusting people, so I used to basically do everything myself. Then, through the Celine project, I finally found a fabricator in New York I really trusted…an absolute nerd about materials the same way I am…so it got way easier to collaborate. It was like, okay, I either keep doing it all, or I let people in and live in the real world.

Academic Ambivalence and Stepping Away

Although Banks Violette earned both a BFA and MFA, he maintains a complex relationship with academia, an unease shaped by growing up in Ithaca, where Cornell University loomed overhead. In his early years, he found little separation between painting, drawing, or welding; it was all “making things.” After finishing grad school, Violette worked for Robert Gober, whose emphasis on the physical act of creation resonated deeply.

Jesse Draxler: So, before you started making these bigger works, like the chandeliers, were you always interested in actually fabricating stuff? You mentioned your dad was basically from a machinist lineage, right?

Banks Violette: Yeah, my dad wasn’t technically a machinist himself, but his dad was, his grandfather was, his great-grandfather was, so I grew up around it. We lived in an old farmhouse in upstate New York. Everything was ‘do it yourself.’ You’re always tearing it apart, fixing it, building it. I never really separated painting or drawing from welding or carpentry. Then in school, they kept them in different silos. I was like, ‘No, it’s all just making things.’ After I graduated, I worked for Robert Gober, who might make donuts and put them in paper bags and call it art. The physical act of making has its own value. That’s how I ended up doing so much myself.

Jesse Draxler: And once your pieces were recognized, I imagine their market value went up. Did that change your sense of ‘value’?

Banks Violette: It’s like being a one-person government issuing currency. There’s no inherent worth…it’s only there because the system says, ‘Yes, this is worth something now.’ I think about that a lot. How’s it created, certified, guaranteed? It’s bizarre. But I still believe there’s this inherent worth in literally making something. That’s what got me into doing it in the first place, being hands-on. So even with bigger stuff, it stayed the same idea.

Jesse Draxler: So would you agree there’s a sort of gatekeeping in fine art, like if you don’t speak that academic language, you’re shut out? Or if a piece doesn’t fit the approved narrative, it’s dismissed?

Banks Violette: I think there’s definitely a dominant conversation…like the ‘certified correct conversation.’ If we all agree these are our footnotes, then we can go deviate from there. But I’m always more interested in these accidents or collapses, like how a destroyed church in German Romantic painting parallels some teen subculture that’s actually burning churches. The second you say, ‘This is what good work is, and that’s not good work,’ you set a category of inclusion and exclusion, which is not interesting to me at all. I’m not in the business of gatekeeping. It’s the conversation that matters, not one single correct vocabulary.

Despite achieving early success, Violette made the deliberate decision to disappear from the art world for several years. His withdrawal was not a sudden collapse but a calculated move…one shaped by personal struggles, exhaustion, and a growing frustration with an industry that, in his eyes, functioned on artificial narratives of redemption and spectacle. The pressure to constantly produce, combined with the unchecked realities of addiction within his circle, led him to step back entirely.

Draxler inquiries into why and how he made that decision, bringing up the New York Times article that framed his return as a dramatic comeback. Violette, however, rejects the idea that his life fits into neat arcs of disappearance and resurgence,arguing that the art world often treats personal struggles as part of an entertaining mythos rather than an actual human reality.

Jesse Draxler: You made an intentional choice to step away from your art career. Can you talk about what led to that? Because I read something, where it sounded like you barely told anyone…you just left, got a house in Ithaca, and kind of vanished. Was that a conscious break?

Banks Violette: I know the New York Times article you’re talking about. That article was one of the reasons why I was like, ‘Oh, I’m going to hit the clock and give myself five more years because this is stupid.’ Which is a terrible thing to say about whoever wrote that, but there’s this stupid narrative about comebacks, right? And sure, it’s great for a movie, but it’s not real life. That whole thing, like, ‘Oh yeah, he’s going to do a show in New York, and he’s back!’ Whatever. So yeah, I moved upstate, got a house, didn’t really tell anybody, didn’t tell my galleries, and just kind of stopped communicating with a lot of people.

Jesse Draxler: How did that go with the galleries? Did they try to hit you up a bunch, or did you just not even have a phone? Like, was there literally no way to contact you anymore?

Banks Violette: Well, the gallery that I was working with at the time, my primary gallery in New York, they folded. Because they were supremely dysfunctional. So I was upstate and suddenly like, ‘Oh shit, I’ve got to find another gallery.’ Thankfully, I already had a relationship with Barbara Gladstone and actually trusted her, so it was an easy fit to say, ‘Hey Barbara, here’s the situation I’m in.’ She kind of knew my history intimately, so it was a smooth segue. But at the same time, I wasn’t super eager to do it. I wasn’t eager to get another gallery, to do a bunch of shows, to make a bunch of work. I needed to test the people I was interacting with, to see if my trust made sense. That sounds vague, but hopefully that makes sense.

Steven Parrino: A Lasting Influence

Steven Parrino, a fellow artist whose work defied easy categorization, left a profound impact on Banks Violette and the contemporary art world. Parrino was an underground icon, his aggressively deconstructed paintings, raw materiality, and punk sensibility made him a figure revered within subcultural circles, yet largely overlooked by the broader art establishment during his lifetime. For Violette, he was a signal of credibility, a kindred spirit, and eventually, a personal friend.

Violette’s decision to exhibit with Team Gallery early in his career was directly tied to Parrino, not because of the gallery’s reputation at the time, but because they showed his work. This alignment speaks to Violette’s deep sense of artistic integrity, where association with the right voices mattered more than commercial success.

Parrino’s tragic death in 2005 struck Violette with a heavy personal blow. The loss was particularly haunting, as Violette was the last person to see him alive. Parrino had been leaving Violette’s house on his motorcycle when he suffered a fatal accident, a detail that imprinted itself so deeply in Violette’s memory that he later created a sculptural elegy to commemorate Parrino’s passing.

As a tribute, he later created a sculptural replica of the motorcycle Parrino was riding that night, disassembling, molding, and casting it in salt before reassembling it. The piece stands as both a spectral presence of Parrino and an elegy to his legacy, embodying the physical and conceptual collapse that Violette has always been drawn to.

Jesse Draxler: I wanted to ask you about Steven Parrino. You’ve mentioned before how significant he was to you, but can you expand on that? What was your relationship with him like?

Banks Violette: He was a friend. I first showed with Team Gallery because they worked with Steven. They were just starting out, didn’t really have a history, and I was still in grad school when they approached me. But once I saw that they were working with Parrino, it was like, ‘of course I’ll show here.’

At the time, nobody really cared about his work, at least not in any mainstream sense. I mean, not nobody…there were a few people who deeply understood it, but he wasn’t getting the recognition he has now. That’s the thing: his work was hugely influential, even if it wasn’t fully acknowledged back then. It was like a secret handshake; if you understood Parrino’s work, you were part of something important.”

Jesse Draxler: It’s interesting because now his work seems even more relevant, more influential than ever. Why do you think that is?

Banks Violette: I mean, the thing is, and I’m not saying ‘Oh, he did it first, so it’s better,’ but a lot of what people now see as seminal gestures in contemporary art. Steven had already done them.

Like, take Cady Noland, who is someone I admire immensely. One of her signature visual devices is the cut-out stockade figures, which she’s used in multiple works. It’s instantly recognizable as a Cady Noland.

But what people don’t always know is that Steven Parrino made a stockade piece before Cady Noland did. It’s not about ‘who did it first,’ but it speaks to how he was already thinking in a way that was shaping the next generation, even if it wasn’t acknowledged at the time.

So when people now look back and say, ‘Wow, his work was ahead of its time,’ it’s because it was. It was like a viral infection, spreading through different generations of artists. That’s why it still feels modern…because the impact of his ideas took years to fully unfold.

Nihilism and Art: Contradiction or Fuel?

Jesse Draxler: I looked up Steven Parrino, and even in the first thing that comes up, it says he was associated with ‘energetic punk nihilism.’ Do you think that’s an accurate label?

Banks Violette: Absolutely not. It was about negating things, and so was Malevich. Or the Ramones. The idea of wiping the slate clean, but you can’t actually do that, because it’s impossible.

If you’ve ever read his writings, there’s a really fantastic collection called No Texts. He talks about negating history, but while doing that, he’s using Robert Smithson’s way of writing about art to prop up his own argument. So it’s ironic, he’s saying he’s wiping history, but he’s using history to wipe history.

It’s like a Ramones song…it’s a dumb punk rock song, but it’s also a 1960s pop song at the same time. It collapses in on itself. That’s why his work is such a slow burn, but inevitably influential. He synthesizes so many different things into one elegant statement, and it takes a while to unpack it. But when you do, you realize, it’s a goldmine.

Jesse Draxler: So what does nihilism mean to you, then?

Banks Violette: I think nihilism is contrary to the production of art. Or maybe that’s cynicism. And I think they’re kind of analogous in a way. But if you’re making something, not to be a hippie about it, but it’s inherently a hopeful gesture.

Like, art is fundamentally communication. You have to have faith in another person if you’re trying to communicate. If you’re truly nihilistic, if you really believe that nothing matters, then you wouldn’t even bother making art. You wouldn’t engage in the process at all. It just wouldn’t make sense.

Jesse Draxler: That’s such a perfect way of putting it. I always say the audience is the final piece of the art. If nobody sees it, it’s incomplete.

Banks Violette: Exactly. If you’re making something and putting it out into the world, then you can’t claim to not care. There’s some level of acknowledgment that an audience exists, even if it’s just one person.

Nature vs. Urban Artifacts: Backpacks Over Trees

Violette’s work is deeply tied to the urban environment, with his inspirations emerging from the everyday objects people modify to reflect their identity, rather than from traditional notions of nature. Jesse asks about how relocating from New York to a more rural setting has affected his creative process, and Violette responds with characteristic bluntness: he doesn’t care about trees. What sparks his imagination are human-made artifacts, particularly within subcultures, whether a self-customized backpack on the subway or a record sleeve from a niche underground band.

Jesse Draxler: Is your process isolated, or do you have a thriving studio with people around? And how has moving to upstate New York changed your creative input?

Banks Violette: That’s been the hardest part about moving here…being away from art. If we accept the idea that art is communication, and you’re in a place where there’s no conversation happening, that’s tough. But also, my work is built on the culture of daily life, the small artifacts we create to make the world feel more understandable. I can walk outside and see a tree. I don’t give a f*ck about trees. But if I’m on a subway and see a kid with a backpack customized in some weird way I’ve never seen before, my brain immediately locks onto that. That’s the shit that gets my brain going. Not trees. I live around a lot of trees. That’s been hard to reconcile.

Jesse Draxler: So what do you do about that?

Banks Violette: You try to stay engaged: through the internet, talking to other artists, seeing exhibitions when you can. But it’s tough. That steady drip of inspiration from urban life is harder to replicate out here.

What’s Next: Pompidou, Antwerp, and Low Frequencies

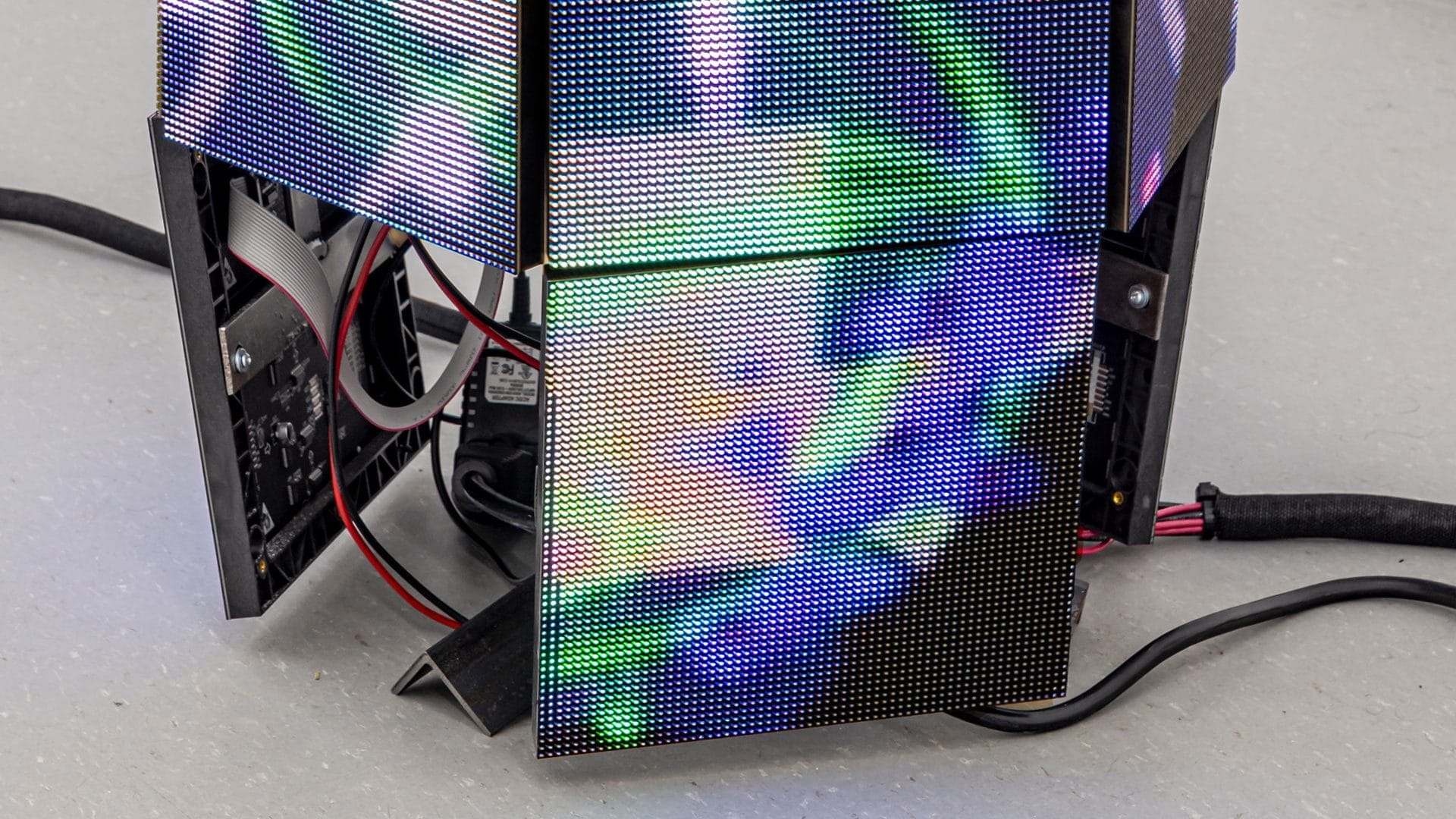

Emerging from a decade-long hiatus, Violette re-engaged with the art world on his own terms, tackling major projects that reflect his ongoing obsession with sound, subculture, and tangible presence. His collaboration with Sunn O))) is being reissued by Southern Lord for Record Store Day, accompanied by a new drawing referencing a coffin from an earlier performance. Meanwhile, a sound-based installation co-created with Stephen O’Malley, built around low-frequency oscillators that can literally vibrate architecture, will be reconstructed at the Pompidou in Paris, having been rediscovered in a late collector’s estate.

Looking ahead to 2026, Violette is planning a major exhibition in Antwerp that explores the interplay of structure and sound through a multi-sensory installation, once again merging raw subcultural impulses, conceptual depth, and a hands-on approach to materials. Although open to potential fashion collaborations, his focus remains on evolving a sculptural and sonic practice that bridges underground aesthetics, personal mythologies, and critical interrogation of art-world norms.

To dive deeper into this conversation, listen to the full-length interview linked below.

fakewhale

Founded in 2021, Fakewhale advocates the digital art market's evolution. Viewing NFT technology as a container for art, and leveraging the expansive scope of digital culture, Fakewhale strives to shape a new ecosystem in which art and technology become the starting point, rather than the final destination.

You may also like

Geoffrey Pugen, Webtology: Prisms at MKG127, Toronto

Webtology: Prisms by Geoffrey Pugen, curated by Michael Klein, at MKG127, Toronto, 15/02/2025–15/0

Meletios Meletiou, Palimpsest – Stratifications in Time at NM Contemporary, Monte Carlo

Palimpsest – Stratifications in Time by Meletios Meletiou, curated by Alessandro Cazzola, at N

Johan F. Karlsson & Dimitris Tampakis, Careful What You Wish For at DISPLAY, Parma

Careful What You Wish For by Johan F. Karlsson & Dimitris Tampakis, curated by Dinos Chatzirafai