Sculpting Society: The Unfinished Revolution of Joseph Beuys

Origins of a Myth: The Body, the War, the Transformation

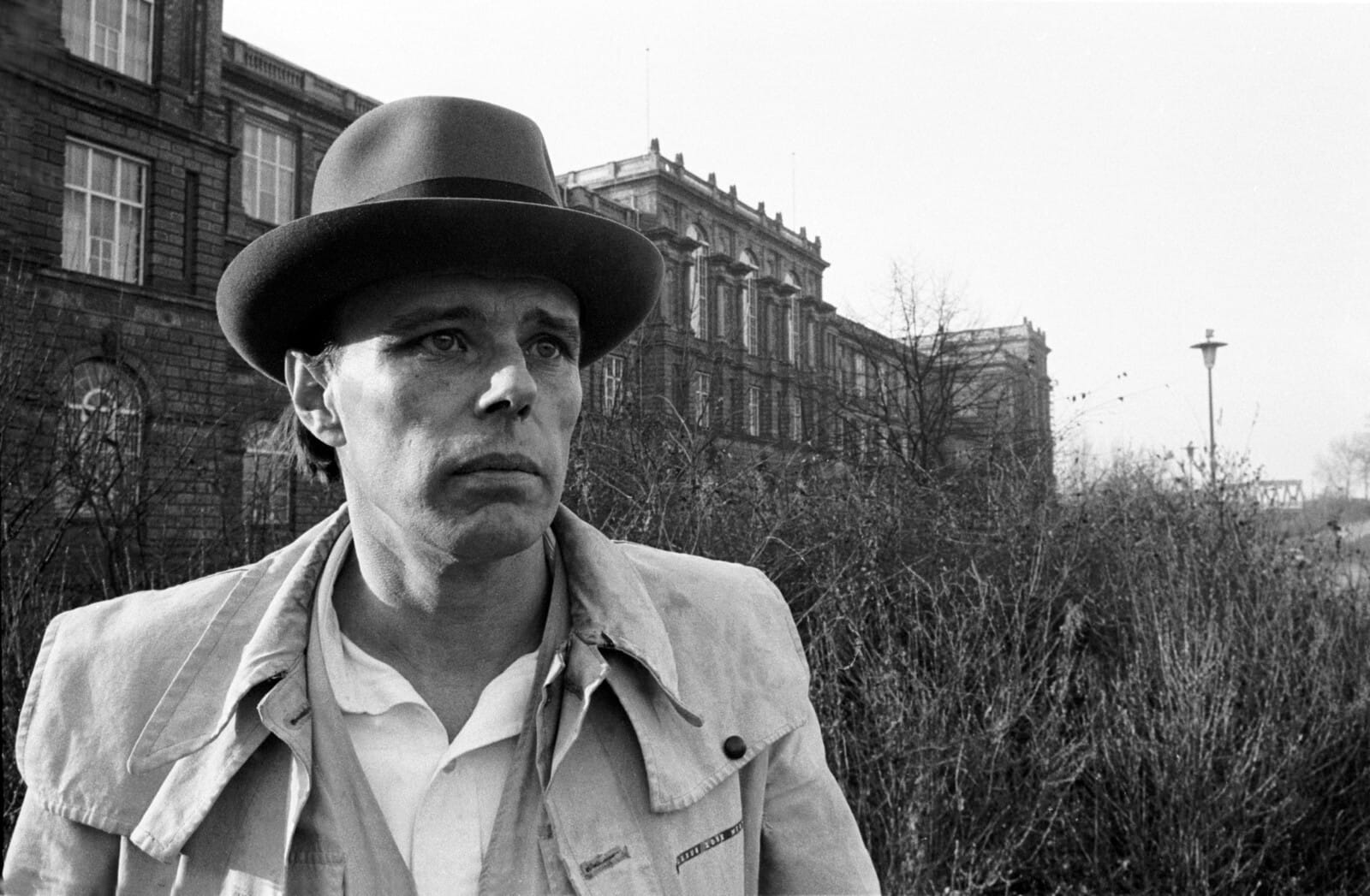

To speak of Joseph Beuys is to enter immediately into an ambiguous space where history and myth intertwine. Born in 1921 in Krefeld, Germany, Beuys did not simply live his biography, he transformed it into material. Central to this transformation is the story of his plane crash during World War II, an event that would become the founding narrative of his artistic identity. According to Beuys, after being shot down over Crimea in 1944, he was rescued by nomadic Tatars who saved his life by wrapping his injured body in animal fat and felt, materials that would later become emblematic of his work.

Whether the story is fact or fiction, many scholars consider it a self-fashioned myth, is irrelevant. For Beuys, personal myth was never a lie. It was a sculptural material. A narrative not to recount history, but to construct meaning. The trauma of war was not simply a memory, it became the theoretical foundation of his practice. Fat and felt were not souvenirs of survival, but symbolic materials, charged with energy, warmth, and protection.

This event was not just biographical. It was conceptual. It signaled Beuys’ refusal to separate life from art. Survival itself became a methodology, and the body, the wounded, transformed body, the first medium. The artist did not create representations of experience. He treated experience itself as sculptural matter.

The war, the wound, the recovery: these did not become stories to tell, but strategies to work with. From this moment onward, Beuys’ practice would center around the idea that transformation is the starting point of creation. Every gesture, every material, every word carried symbolic weight. Beuys didn’t position himself as a conceptual artist or a performer. He became both author and artwork simultaneously. His body was no longer private space. It was a public site, a theoretical vehicle, and a conceptual platform.

Before being a theorist, a performer, or a teacher, Joseph Beuys was a survivor who turned his own body into the raw material from which to rebuild everything.

Social Sculpture: Redefining Art as Collective Process

If there is one concept that defines Joseph Beuys’ philosophy, it is social sculpture, an idea as enigmatic as it is radical. With this term, Beuys proposed nothing less than the expansion of sculpture beyond the physical object. For him, sculpture became a living process capable of shaping ideas, social structures, and even economic systems.

Beuys believed that every human being carries an innate creativity. Not only artists: everyone, potentially, is a social sculptor, shaping the living body of society through actions, words, and relationships. Art is no longer confined to specialists or professionals, it becomes a form of distributed energy, an invisible force that can drive transformation on a collective scale.

From the 1960s onwards, Beuys sought to embody this idea through practice. He founded discussion groups, alternative schools, and political movements, all rooted in the conviction that art dissolves into life precisely to change it. In 1972, during Documenta 5, he launched the Free International University, a public forum where theory, art, and politics merged without hierarchy. In these spaces, Beuys did not present himself as a master, but as a catalyst. His goal was not to teach, but to activate, a process of awakening others to their own creative potential.

Social sculpture was never meant as a metaphor. It was a pedagogical and political method. A form of teaching that rejected vertical knowledge and a politics that extended beyond party structures. For Beuys, art was the true infrastructure, not a product, but a method of organization.

His famous motto, “Everyone is an artist”, was not a slogan of naïve optimism. It was a foundational claim: that every human act carries the potential to shape the world. Art, understood as universal creativity, is not ornamental but revolutionary. It is the latent force capable of redesigning reality itself.

For Beuys, sculpture was never about form.

It was always about force.

A living structure, continuously reshaped by human action.

A sculpture we are all part of.

Actions and Rituals: Between Performance, Symbol, and Pedagogy

At the heart of Joseph Beuys’ practice lie his actions, not conventional performances, but ritualistic interventions designed as symbolic gestures, pedagogical exercises, and conceptual devices. Each action was not an event to observe, but an enigma to inhabit.

Among his most iconic works is I Like America and America Likes Me (1974). Beuys arrived in New York wrapped in felt, transported directly from the plane in an ambulance to the René Block Gallery. For three days, he shared the gallery space with a wild coyote. The animal became a living symbol: representing a forgotten nature, the spirit of pre-colonial America, and the possibility of a non-verbal dialogue between human and animal. Beuys didn’t tame the coyote. He coexisted with it, a suspended exchange of gazes and gestures, unresolved, yet charged with meaning.

Equally enigmatic is How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare (1965). With his face covered in honey and gold leaf, Beuys cradled a dead hare, walking slowly through the gallery and whispering explanations into its lifeless ears. Here, pedagogy itself is inverted: knowledge is not transmitted to the living, but entrusted to the mute, the inert, the incomprehensible. Who can understand art? Who is it really addressed to? For Beuys, perhaps the dead are the only ones who listen.

In Celtic (Kinloch Rannoch) (1970), he walked across the Scottish landscape, tracing the earth with his staff, half shaman, half surveyor. The landscape itself became a surface, a page, a field to inscribe.

All of Beuys’ actions are constructed as secular liturgies. Every material, every gesture, every presence functions as a symbolic tool. The audience is not there to witness, but to be implicated, to be subtly repositioned in relation to what they think they know.

Felt, Fat, and Other Metaphors: The Symbolic Materiality

In Joseph Beuys’ universe, materials were never just materials. They were conduits of energy, repositories of memory, tools for thought. Above all, felt and fat became the most emblematic elements of his visual and conceptual language, two modest, industrial, even mundane substances that Beuys elevated into symbolic foundations of his practice.

According to Beuys’ personal myth, felt was the material that saved his life after his plane crash in Crimea, used to insulate his wounded body from the freezing cold. But in his work, felt was more than anecdote. It became a physical manifestation of stored warmth, of protection, of isolation from external forces. In his installations, felt served not just as barrier but as membrane, a conceptual surface capable of absorbing, containing, and regulating flows of energy.

Fat, by contrast, embodied transformation itself. Organic, malleable, unstable, fat could solidify or liquefy, shifting according to temperature. For Beuys, it symbolized latent potential, energy awaiting release. Fat was both physical material and philosophical proposition: the materialization of change, of instability, of hidden vitality.

These substances appear obsessively throughout his work. Sculptures wrapped in felt, objects embedded in fat, installations combining these with copper, wax, or honey. In Fat Chair (1964), a simple block of fat slowly melts and deforms over a wooden chair, time itself becoming sculptural material. The object is not a finished form, but a process in flux.

Even copper, a conductor of electricity and heat, carried metaphoric significance: the invisible circulation of energy. Beuys used copper not for its aesthetic qualities, but to suggest movement, flow, and unseen connections.

Beuys did not work with materials for their appearance. He worked with them for their function. Each element was a reservoir of potential, a latent message embedded within matter. In his hands, materials became theories, made tangible.

More than a traditional sculptor, Beuys operated as a modern alchemist. He transformed the ordinary into the conceptual, the physical into the philosophical. He didn’t sculpt forms.

He sculpted meanings.

Art and Politics: The Party, the Revolution, the Economy

For Joseph Beuys, art was never a separate sphere of life. It was a political tool. Not political in the traditional sense of propaganda or party allegiance, but as a transformative force, capable of redesigning structures, economies, and ways of thinking.

This vision took concrete form in the 1970s. In 1967, Beuys founded the Organization for Direct Democracy through Referendum, a political platform disguised as an art project, or perhaps the reverse. He also created the German Student Party, a fictitious yet operational entity designed not to seize power but to provoke dialogue. For Beuys, these were not ideological exercises, but practical demonstrations: proof that politics itself could be treated as a sculptural process, a form to shape, to rethink, to reimagine.

His political engagement extended into environmental activism. His project 7000 Oaks (1982), presented at Documenta 7, stands as his most monumental gesture: the planting of seven thousand oak trees in Kassel, each paired with a basalt stone. A living, growing installation that blended ecological restoration with public art. For Beuys, the tree was a living sculpture, and the city itself became a site for aesthetic-political intervention.

At the heart of his thinking was a radical critique of capitalism. In 1979, he coined the phrase “Art = Capital”, not as an endorsement of the market system, but as a provocation. If capital is society’s productive force, then creativity, universal, human creativity, is the true capital. His proposal was utopian yet structured: to redesign the economy itself as a creative process, where value is generated not by commodities but by the imaginative capacities of every individual.

This led to his theory of the “creative economy” an alternative model where every human being contributes to production through their inherent creativity. In this framework, art is no longer a luxury or an industry. It becomes the foundational structure of society’s value system.

Beuys rejected the role of the isolated artist. He envisioned himself as a facilitator of possibility, an agent of real change. For him, art was not a reflection of society.

Art was society itself, still in the process of being shaped.

A project still unfinished.

A revolution not of aesthetics, but of structure.

Beuys’ Legacy: Between Utopia and Institution

Decades after his death, Joseph Beuys remains a contested figure in contemporary art. How does one preserve the work of an artist who didn’t aim to produce objects, but to activate processes? Who didn’t offer a style, but a method?

On one level, Beuys has been fully absorbed into the institution. His felt, his fat, his relic-like installations are housed in museums, photographed, catalogued, and exhibited as icons of 20th-century art. His actions, documented in video and photography, have become milestones in art history textbooks. In this sense, Beuys, the revolutionary, has been institutionalized.

And yet, the core of his work resists capture. Because what Beuys left behind was not just objects, but a vision. A concept of art as an active force, where the artist is a social sculptor, and the viewer is not a passive spectator but latent material awaiting activation.

His legacy remains deeply ambiguous: was Beuys a modern shaman, or a failed teacher? A visionary thinker, or a naïve utopian? Perhaps the truth lies precisely in that tension. His work does not resolve itself into answers. It opens questions. His legacy is not a doctrine, it is a methodology: transform, activate, intervene.

Today, much of participatory, ecological, and socially-engaged art operates in Beuys’ shadow. Yet there’s a risk of misunderstanding him. Beuys did not advocate for feel-good participation or superficial collectivity. He proposed something far more difficult: a constant confrontation with transformation itself.

In a world that craves resolution, Beuys offers instability as method.

His work is not a place to arrive. It is a space to remain unsettled.

His legacy is not to be celebrated.

It is to be practiced.

And perhaps, to be risked.

fakewhale

Founded in 2021, Fakewhale advocates the digital art market's evolution. Viewing NFT technology as a container for art, and leveraging the expansive scope of digital culture, Fakewhale strives to shape a new ecosystem in which art and technology become the starting point, rather than the final destination.

You may also like

A Narrow Strip Along a Steep Edge at Fort Lytton, Brisbane

A Narrow Strip Along a Steep Edge by Angel, Charlie Robert, Dean Ansell, Jessica Dorizac, Max Athans

Fakewhale in Dialogue with Sizhu Li

Having lived and worked across two continents, Sizhu Li has cultivated a distinctive artistic langua

Fakewhale in Dialogue with Jacopo Benassi: The Visceral Tension of an Uncompromising Vision

Fakewhale had the pleasure of speaking with Jacopo Benassi, a multifaceted artist who moves fluidly