Fakewhale in Dialogue with the Jakob Collection: Rethinking Patronage and the Anti-Hero

A curious observer and unconventional collector, Lukas Jakob has turned his young age into a strength, building a collection that goes beyond simply accumulating works. His approach explores the fragilities, contradictions, and urgencies of our present moment. The Lukas Jakob Collection stands out for its focus on anti-heroic practices, complex digital processes, and exhibition formats that step outside the conventional white cube…

What fascinated me most at the time was how Katharina Grosse completely redefined painting. That a picture doesn’t have to exist solely on canvas, but can emerge anywhere, ,on walls, floors, even in forest clearings. This radical expansion of what painting can be captivated me instantly. From the very beginning, I was also deeply impressed by listening to her speak about her work, by the clarity and consistency with which she reflects on her artistic decisions. Walking through the current exhibition at the Staatsgalerie Stuttgart was an uplifting experience. Many of her works are ephemeral, they disappear once the exhibition ends. What remains are often fragments that carry a fragmentary aesthetic. For me, these pieces are like mementos of exhibitions, traces of experiences that have stayed with me. My interest in this kind of radical approach still shapes how I look at art today. I can hardly engage with painting without sensing Grosse in the background. At the same time, I listen closely to what moves young artists. Their perspectives often offer vital impulses for a progressive society, and I’m committed to helping make their themes and concerns visible.

You’ve often said you don’t see yourself as an owner of art, but as a patron, a word that evokes protection, responsibility, and care. But what does that really mean in everyday practice? What does it look like, for instance, to care for a fragile work, a young artist, or even just an idea?

First of all, many of the works in my collection destroy themselves. So it’s a constant process of looking after them with care. I find it truly exciting to build long-term relationships with artists. When dialogues emerge between artists and scientists, sociologists, philosophers, and others, it opens up new ways of supporting their work and discussing it in broader contexts. I think, for instance, of a fascinating talk between professors from the University of Freiburg on the work of Thomas Liu Le Lann, held during his solo exhibition at E-WERK Freiburg in 2024. Building these kinds of bridges is something I find deeply meaningful. I greatly value the collection of the ZKM in Karlsruhe. In the collection’s current exhibition, the team had to work with a gaming community to restore a work by Paul Garrin, as the artist had originally used, among other things, special software that has particular technical features. That level of curatorial care made a lasting impression on me, and it’s exactly the kind of commitment I hope to maintain for my own collection in the future. We continuously acquire equipment, explore new ways to present works, including lighting, sound technology, and digital archiving across various formats and cloud systems. I also advocate for making outstanding young artists visible in digital encyclopedias, and I give talks about the works in my collection, most recently at the Museum für Neue Kunst in Freiburg and at LISTE Art Fair.

“I collect the present,” you’ve declared. But the present is never fixed. What are the signs, for you, that a work truly captures the spirit of its time and perhaps even pushes beyond it?

My current interest lies in anti-heroic themes. A key impetus was Ulrich Bröckling’s essay Post-heroic Heroes, A Portrait of Our Time, in which he questions whether we still need heroes in a world structured by organization and technology, and how heroism is being redefined today. The classical hero has become obsolete, replaced by fractured figures who offer guidance not through greatness, but through humanity. I belong to a generation caught between resilience and exhaustion, between digital hyperconnectivity and social fragmentation. Our heroes are not triumphant, but ambivalent, overwhelmed, and complex. Portuguese photographer Jaime Welsh, for instance, uses editing software almost like a painter uses a brush. His staged images often show isolated figures in monumental, authoritarian-looking spaces. His meticulous process, from location scouting to post-production, creates psychologically charged scenes filled with tension and unease. Julian-Jakob Kneer tells the story of a masked anti-hero, drawing on visual codes from film and pop culture to explore fame, narcissism, longing, and self-destruction. When artists engage with pop culture, fashion, or politics, they respond directly to the urgency of the present. I’m also reminded of Rindon Johnson’s video I First You (11/11), which I acquired in the year it was created, 2018. It presents a floating, virtual landscape filled with voices reflecting on intimacy, loss, and political upheaval. The text, written on the day of Trump’s election, marks a turning point into a more violent reality. Personal moments, like the arrest of a loved one, mirror the political vulnerability of queer existence. Through these works I am also constantly learning new things about music, film, technology, history and sometimes deeply personal experiences.

Some of the Jakob Collection’s most striking projects have been staged far from the conventional white cube: a chapel, a butcher shop, a power station. What draws you to these non-traditional spaces? Is it an aesthetic choice or does it speak to a broader methodology?

Often, it’s simply because the art spaces themselves are based in these kinds of locations. They are exciting venues with fascinating histories of adaptive reuse, and they contribute to what makes the museum landscape in the tri-border region (Germany, France, Switzerland) so dynamic. Creating a dialogue between the exhibition architecture and the artworks is a compelling approach. As things stand today, I would almost always choose a vacant industrial hall over a white cube when thinking about the collection. Just look at how beautifully the Basel Social Club or Paris Internationale benefit from this kind of setting every year. Even when such spaces can feel overwhelming at times, they are usually the ones that leave the most vivid and lasting impressions on me.

Your digital presence is a key part of the project. Still, you’ve voiced concern that many artists risk getting lost in the algorithm. How do you reconcile reach and depth, visibility and complexity, in how you share and support contemporary art?

My strong online presence mainly stems from the fact that I don’t have a museum of my own, I’m only 27, and the internet offers me the best way to share the artworks that mean so much to me with people all over the world, spreading my enthusiasm. Many of my friends are scattered globally, and I actually started engaging online early as a teenager. How could one blame me? Freiburg is not a metropolis like Berlin, so connecting globally from home was a natural choice. My digital approach is to always accompany any shared work, whether a video or photo documentation of an exhibition, with detailed information about the artwork and proper credits. This ensures that the work is engaged with beyond mere aesthetics, especially important for the conceptual art I collect. Of course, this can never replace seeing an exhibition in person. And in my view, no well-designed PDF can substitute the experience of leafing through a thoughtfully produced printed catalog, but both formats have their important role.

Has there ever been a work that truly challenged you physically, logistically, maybe even emotionally? We’re thinking of large-scale or difficult-to-install pieces. Did any of them make you reconsider the limits of collecting ambitious works?

Without a doubt, Thomas Liu Le Lann’s slumpe soft-hero was a pivotal moment in the collection. I discovered the work at LISTE in Basel, just as we were finally able to return to art fairs after the long pandemic pause. And there he was, sitting on the floor: this deflated, oversized superhero who had seemingly given up on the world around him. For me, he captured a feeling I deeply identified with at the time. In the Soft Heroes series, he deals with the elaboration of fictions inspired by popular culture. In this way, he creates these soft sculptures that are installed on the floor as figures without a face or expression, whose only visible attitude seems to be that they have given up on the world around them. The gigantic figures are slack, sometimes bordering on formlessness, like overworked, modern and tired superheroes. Dressed in a harlequin mask, they could also be on their way to the next bank robbery. Social psychologist Philip Zimbardo once wrote: “Heroism shifts our focus to the best of human nature. We love to hear heroic stories because they remind us that humans are capable of resisting evil, avoiding temptation, rising above the ordinary, and answering the call to act and serve, especially when others do not.” In terms of logistics, transporting and storing the piece is actually less challenging than one might expect, as it’s a soft sculpture. The real difficulty lies in presenting it: at seven meters in length, the work requires a large, open space to be properly shown. I am delighted that these tender heroes are currently populating the Villa Merkel in Esslingen, the Kunstmuseum Heidenheim and the Xippas Gallery in Geneva at the same time.

Several of the pieces you’ve supported most deeply, like Gabriella Torres-Ferrer’s We Are All Under the Same Sky, grapple with invisible technologies: networks, data, surveillance. How does the Jakob Collection reflect or amplify these themes in today’s post-digital context?

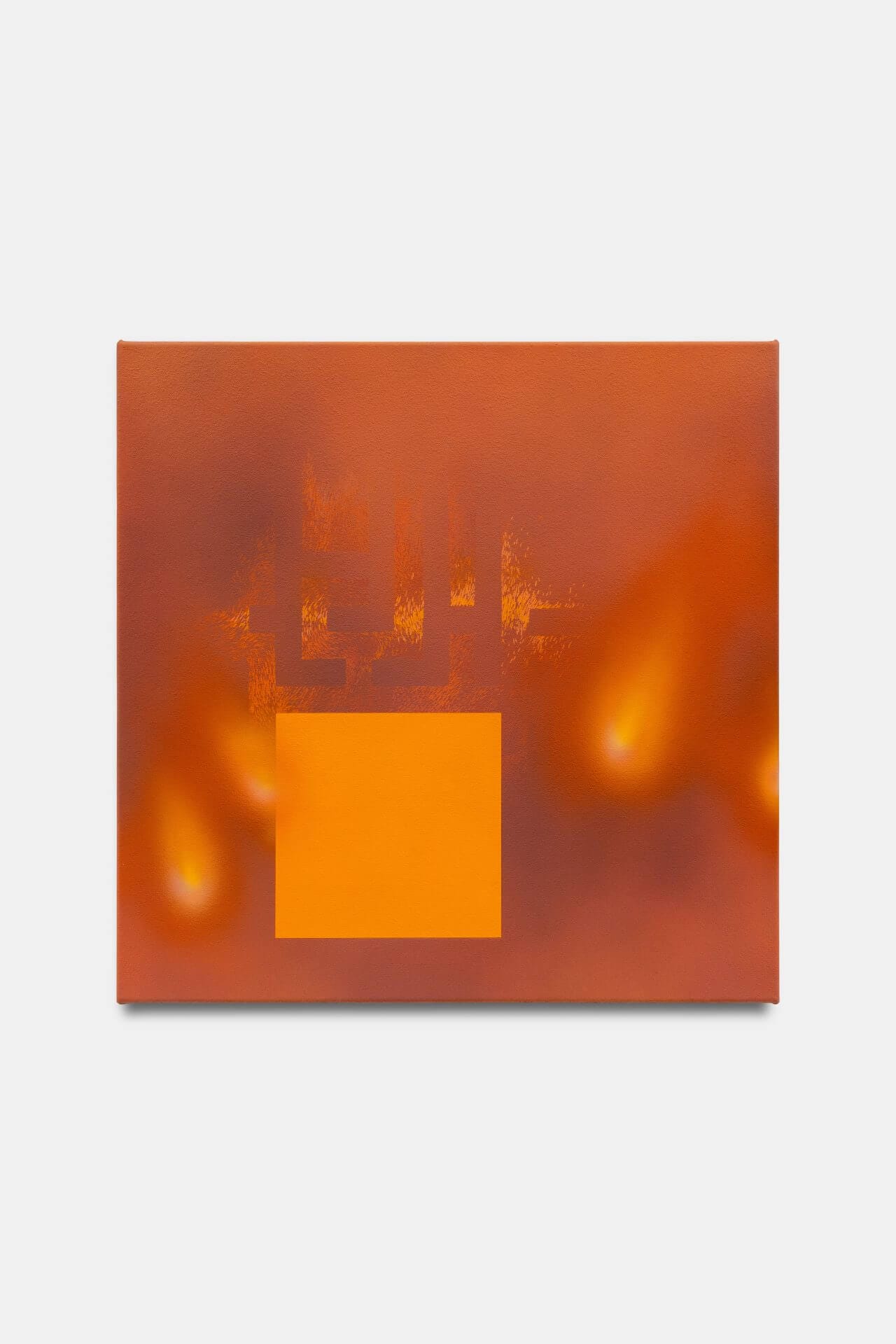

Gabriella Torres-Ferrer’s work is embedded in a broader context within the collection, one that explores the interconnection of complex systems, from digital technologies to global power structures. Much like Natacha Donzé’s apocalyptic visual worlds, Torres-Ferrer challenges hegemonic narratives through alternative perspectives. By combining natural materials and everyday objects with digital processes, his installations offer ironic critiques of consumer-driven societies. This becomes especially striking in the context of post-hurricane Puerto Rico (2017), where large corporations profited from the crisis while much of the population was left in ruin. His installation We Are All Under the Same Sky reflects this tension: interactive sound sculptures made of modified emergency blankets shaped like golden clouds, which respond to movement in the space. The piece centers on digital surveillance, data collection, and social profiling. Natacha Donzé’s approach, by contrast, is painterly: her airbrush-based works evoke thermal images, explosions, or microscopic cells. Drawing from science, pop culture, encyclopedias, and satellite imagery, she constructs luminous, fragile landscapes that reflect ecological and emotional overwhelm. In Memory-resident (yellow) (2024), she explores environmental warning signs, like blinking devices or animals changing color, translated into digital swarm logic, mirroring how information travels from screen to screen, like a technological migration of birds. In her work, Vincent van Gogh’s expressive brushstrokes meet Josef Albers’ constructivist geometry, and digital firewalls. My personal interest in these themes is also informed by my professional experience working with sensitive personal data and public information systems.

Being featured as the youngest collector in the BMW Art Guide placed you under a certain spotlight. Has that visibility changed the way you engage with artists and galleries, or has your approach remained consistent?

The BMW Art Guide has been an especially exciting opportunity for me to connect with so many inspiring collectors and to learn about their stories and experiences. In addition to my deep interest in artists, I’ve long been fascinated by private collections. I often turn to the Guide to discover and visit these remarkable places. I’m very grateful to the team at the BMW Art Guide and Independent Collectors for making this possible. I’m already looking forward to hearing from the next generation of collectors in the upcoming edition. My curiosity and enthusiasm for these stories remain unchanged.

At fairs, you alternate between established blue-chip galleries and emerging sections where everything hinges on a first impression. How do you decide when it’s worth taking a risk? Have you developed a kind of instinct, or do you rely more on structured criteria?

At the end of a walk through an art fair, I often ask myself two questions: What truly stayed with me, and what did I not understand at all? In reflecting on this, I deeply value conversations with gallerists whose perspectives I trust. One gallery I’ve been following closely for some time is Blue Velvet Projects. Their program is thoughtfully curated, and their fair presentations are conceptually precise and visually striking. Putting trust in this ambitious new generation of gallerists has consistently proven worthwhile. Taking a risk is often rewarding, especially when a work clearly enriches the collection on a thematic level. Sometimes, works also take on new relevance in unexpected contexts: In 2023, a video of a piece by Evgenij Gottfried from one of our collection presentations went viral, shared millions of times, turned into a meme, and even repurposed for a national DIY store campaign. This sparked a broader debate about DIY aesthetics, spectacle culture, and artistic value in digital spaces. To this day, people still ask me about that artwork I first discovered and acquired in a small municipal gallery for emerging art here in Freiburg years ago.

You grew up at the crossroads of Germany, France, and Switzerland, a tri-border region you’ve described as formative. Now that you’re navigating an increasingly global art ecosystem, how do you envision the future of the Jakob Collection? In what direction are you headed, and with what sense of urgency?

fakewhale

Founded in 2021, Fakewhale advocates the digital art market's evolution. Viewing NFT technology as a container for art, and leveraging the expansive scope of digital culture, Fakewhale strives to shape a new ecosystem in which art and technology become the starting point, rather than the final destination.

You may also like

Sandra Mujinga, Skin to Skin at Stedelijk Museum, an Interview by Matteo Giovanelli

On September 11th, the Stedelijk Museum (Amsterdam, NL) opened Skin to Skin, the new solo show by Sa

Crafted for Your Attention: As Predictable as Art

There’s something deeply alluring about predictability. It’s like a mental embrace, a kind of li

Fakewhale Solo Series presents A Symbol at the Surface by Vidal Herrera

On Wednesday, May 29th, Fakewhale proudly presents “A Symbol at the Surface”, a Fakewhale Solo S