Curating Otherwise: Interdependence as a Tool to Practice

When the old is dying and the new delays, a counter-movement rises in the infrathin of the now. Outside the prestige ecosystems of museums, biennials, and the increasing artist-run spaces, the figure of the independent curator moves on unsteady grounds marked by precarity given by the ongoing lack of structural support. Independent (emerging) curators, despite being essential interlocutors in contemporary art discourse, often navigate terrains of exclusion when unable to access funding mechanisms, artistic residencies, and established curatorial development pipelines.

The “independent” curator is yet a luring figure in contemporary culture: nimble, inventive, self-authoring and so malleable. Yet in practice, independence sometimes means invisibility. The myth of autonomy obscures the reality of under-compensation, overwork, and lack of safety nets. Even within so-called alternative spaces, curators are often marginal – perceived as supplementary to the “real work” of artistic production, or viewed as opportunistic intermediaries. This outlook not only undermines the specificity of curatorial labor, but erases the political, emotional, and infrastructural work that independent curators do every day. Writing, budgeting, facilitating, advocating, mentoring, mediating, none of this is “just admin.” These are all at the core of curating, often developed at the margins.

Residencies are now a cornerstone of global art infrastructure yet curators are rarely included in these systems, and when they are, the invitation tends to be instrumental, offering visibility to a program, not care to the practitioner. The idea that curators can simply “join” existing artist residencies misunderstands the nature of curatorial practice, which is often processual, dialogical, and long-term. Without dedicated residencies, there is no structured space to develop new curatorial vocabularies, especially ones rooted in collective care, experimentation, or alternative knowledge systems. Even fewer opportunities exist for curators whose work centers activism, healing, or marginalised communities.

Without institutional anchoring, independent curators are rarely eligible for funding that might otherwise support such modes of working. This is not just an issue of access. It’s a structural erasure of a form of cultural labor that does not conform to metrics of productivity or spectacle. The exclusion of curators from residencies reflects a deeper problem: a fundamental misunderstanding of what curating is, and what it could be if understood as a profession in transformation and change. Care is not a warm affect. It is a system: of time redistribution, of boundaries respected, of labor made visible, of access engineered, of exhaustion named and shared. Most purveyors of cultural representation, curators must move from independence to interdependence not to deny the specificity of each curatorial voice, but to insist that no one curates alone and not solely for the spectacle of the display. Every exhibition, text, or public program is shaped by networks, of dialogue, support, critique, conflict, inspiration. Acknowledging these relations does not weaken the authority of the curator, it makes it accountable, alive, and plural.

An interdependent curatorial practice is built on reciprocity. It foregrounds transparency around fees and conditions, co-authors outcomes, shares contacts, opens up credit lines, and pays attention to who is being left out or talked over. It involves asking uncomfortable questions: Who can afford to do this work? Who is subsidizing whom? And so on. It also involves designing counter-infrastructures. These don’t need to be large-scale institutions. They can be chats, walks, peer review circles, meal-based meetings, toolkits, conversations, book swaps, text messages, audios, and any form of communication.

What if every grant had a line for “curatorial care work”? What if residencies funded curators to simply rest or read? What if peer learning was formalized through traveling fellowships, collaborative research labs, or mentorship pods? What if unpaid opportunities were collectively boycotted? What if we stopped asking, “What is your curatorial vision?” and started asking, “Who do you hold close, and how do you hold them?”

“Love persists alongside exhaustion, tenderness alongside resentmentment. Not because we lack devotion, but because no relationship can replace public infrastructure.” (Bare Minimum Collective, An Accumulation of Care, 2025).

The “now” of curating, and the future too,must therefore be built on interdependence as a method. Yet the interdependent curator’s marginal position also opens a space for unsettling paths, one sustaining life at the margins. From this space, a different curatorial ethos is possible, one that values slowness as an infrastructure drawing conditions to build networks of care and dialogue. Considering interdependence brings to the forefront tha “‘relationships are what stay with us once the work or project is over,” to quote Tian Zhang’z A manifesto for radical care or how to be a human in the arts. (1)

Reclaiming relation-based curating practices instead of project-dependent ones: for a practice based on long-term nets of support rather than fast-consuming art and curating practices. Reclaiming criticism over superficial dead-ended feedback loops. Reclaiming social imagination over fixed curatorial paths for the privileged.

- Tian Zhang. A manifesto for radical care or how to be human in the arts. Agnes Etherington Art Centre on the occasion of An Institute for Curatorial Inquiry, 2022. Originally published by the Sydney Review of Books, 2022.

Ilaria Sponda

Ilaria Sponda is an in(ter)dependent curator, writer, and editor. She lives and works in Munich. She holds a BA in Arts, Media, and Cultural Events from IULM University, Milan, and a MA in Culture Studies at Universidade Católica Portuguesa. Her words have featured in The British Journal of Photography, C41 Magazine, Lampoon, Over Journal, Umbigo and Trigger among others. Her focus of interest lies in photographic art, media ecologies, globalization, and image circulations. She works at the intersection of contemporary art, image-culture and their distribution. Her research and work are rooted in in(ter)dependence as a curatorial practice itself. Her curatorial work has indeed been supported by alternative dialogical work of knowledge sharing outside common circuits of financial support given both the current economic crisis and exclusion policies at play in the art world. Her commitment to questioning the curatorial redefines the parameters of the artist-curator relationship, inviting a reexamination of how cultural knowledge is generated and disseminated in our interconnected world.

You may also like

Graffiti. From the Spray Paintings & Underground to the Museion

Discussing graffiti in a museum context can be uncomfortable and unsettling. This is due to the deli

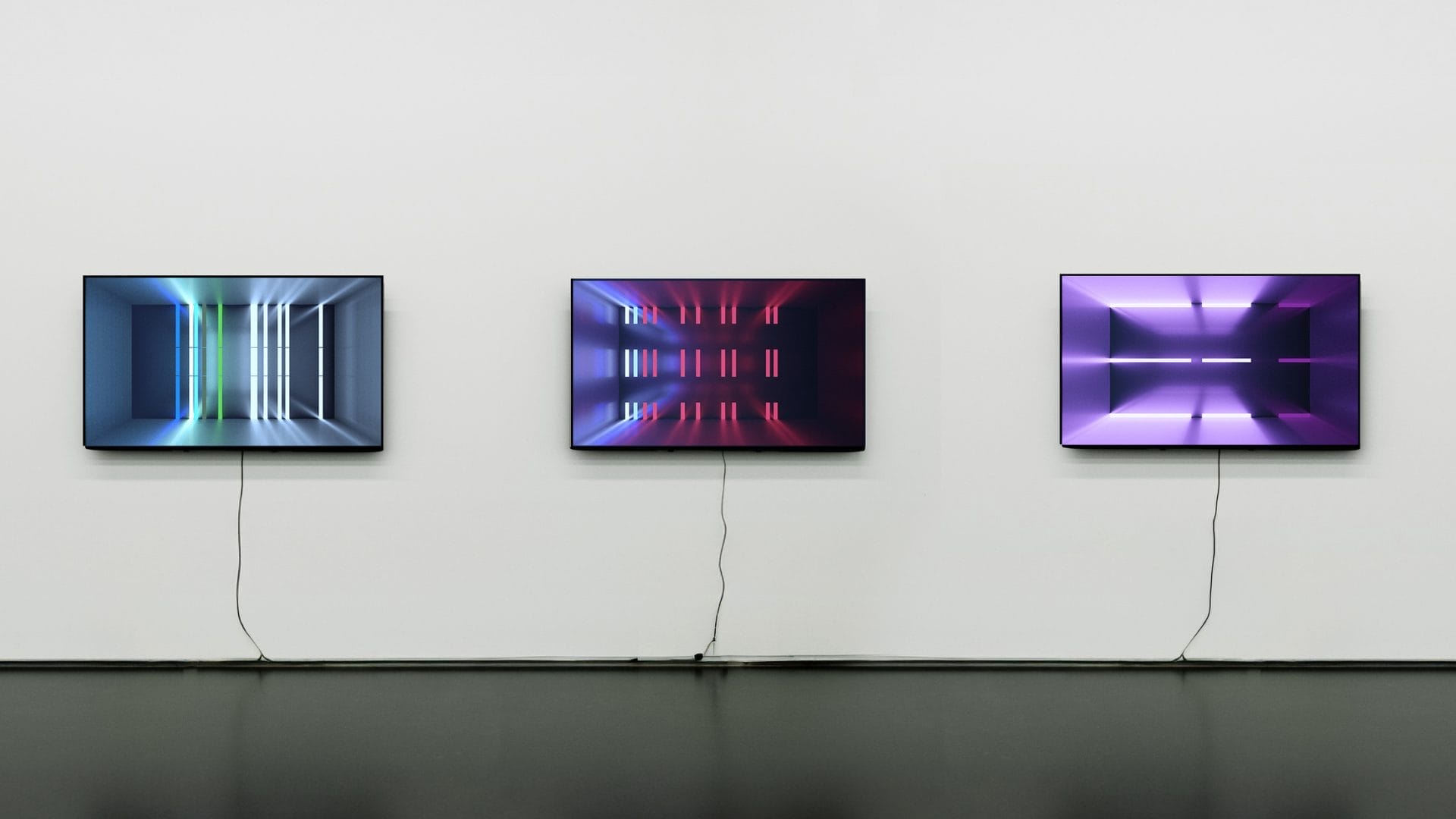

Fakewhale Gallery Presents cornell_Box by Andy Duboc on Verse

On April 16th, 2025, Fakewhale presents “cornell_Box,” a Fakewhale Gallery generative art releas

FW Spotlight: Top Submissions of December

Tradition and modernity collide like tectonic plates, their friction fueling questions of identity a